Business

Page: 101

Nearly three decades after launching NYC’s Fleadh Festival celebrating global Irish culture, two of Fleadh’s founders Joe Killian and Liam Lynch are again joining forces to premiere Seisiún, an Irish music and cultural gathering at Suffolk Downs in Boston.

The Sept. 6-7 event will be produced in partnership with The Bowery Presents, Lynch and Killian, featuring The Pogues and Boston’s own Dropkick Murphys as headlining artists. The Pogues will include original members like banjoist and songwriter Jem Finer, accordionist James Fearnley and tin whistler and singer Spider Stacy. Seisiún will be the Pogue’s first show in the U.S. since the passing of former frontman Shane McGowan in 2023 and the set will celebrate the Irish folk-punkers entire body of work “while honoring Shane, leaving space for alchemy and magic from very special guest performances,” a press release announcing the show reads. A statement from the band confirmed appearances from “such incomparable artists as Lisa O’Neill, John Francis Flynn and The Bad Seeds.”

The band also said: “We are stoked to return to Boston, pretty much a second home for The Pogues in the US – a city where we have shared many unforgettable performances and experiences. We’re looking forward not just to raising a glass or two but also to raising the roof with our fans and friends, old and new, to celebrate the music we’ve made and the alliances we’ve formed over the years.”

Trending on Billboard

Other artists on the bill include The Hold Steady, The Waterboys, Cardinals, The Rumjacks and Lisa O’Neill. Additional artists will be announced in the future.

Seisiún was created as a two-day festival experience celebrating global Irish music and culture and honoring the memory of the first Fleadh Festival in 1997 on New York City’s Randall’s Island. More than 60,000 music fans attended Fleadh to see sets by McGowan and his band the Popes, Sinead O’Connor, John Prine, Van Morrison and more.

“We’re launching Seisiún at a time when Irish culture is once again witnessing another rich revival and resurgence. There is such an exciting wave of extraordinary cross-category Irish music talent,” explains Lynch. “With this two-day event our hope is to reignite some of that same sense of gathering, of revelry and of community, while also tapping into that emergent new interest in the genre. Let the music keep our spirits high.”

Tickets for Seisiún will go on sale to the general public on Friday at 10 a.m. ET via AXS.com, the official ticketing outlet for The Stage at Suffolk Downs. Visit StageAtSuffolkDowns.com for more information.

AEG Presents is finally planting its flag in Austin.

While the city has long been the home of Messina Touring Group — AEG Presents’ highly successful global touring outfit — the live music giant hasn’t held any real estate in the fast-growing metroplex.

That changes now that AEG has announced plans to open a 4,000-capacity indoor venue in the so-called “live music capital of the world.” The 65,000-square-foot, yet-to-be-named venue will anchor River Park, a 109-acre mixed-use development in East Austin that will combine residential housing with office space, retail and restaurants.

“Designed for both world-class performances and unforgettable events, the venue will feature state-of-the-art sound and lighting, luxury suites, VIP seating, and best-in-class hospitality — all with a front-row feel no matter where you’re standing,” a press release announcing the project reads. “The artist experience is just as carefully considered with spacious, artist-friendly dressing rooms, green rooms, and top-tier production capabilities.”

AEG Presents attorney Shawn Trell explained that the company has “always wanted to build a venue from the ground up in Austin, but we wanted to make sure the timing and location were right, and we had partners aligned with our vision.” Those partners include Texas developers Presidium and Partners Group.

Trending on Billboard

Austin has seen a number of new venues open in recent years, dating back to the opening of ACL Live at The Moody Theater in 2011. A year later, Live Nation and the Formula 1 racing association opened the Circuit of the Americas, which features auto racing and large-scale concerts. And in April 2022, Oak View Group opened the Moody Center, an 18,000-capacity arena that is regularly listed on Billboard Boxscore’s chart of top venues with a capacity of over 15,000.

“We’re thrilled to bring a new venue to Austin, a city that lives and breathes live music,” said Robin Phillips, vp of AEG Presents Southwest, in a statement. “Our mission is to bring something new to the city that both honors the legacy of Austin and feels completely unique. Whether it’s a headlining show from a national touring act, or a local artist’s breakthrough moment, we want this space to feel like home for musicians and fans alike.”

Whether it was Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” LiAngelo Ball’s “Tweaker,” or the six songs at the heart of Drake and Kendrick Lamar’s epic rap battle last year, Billboard has recently spent a lot of time reporting on how much money a hit song generates.

For a look back at our coverage, we estimated how much the top 10 songs of 2024 earned, what GELO’s locker room anthem has netted, and the millions made from Drake and Lamar’s diss tracks.

Trending on Billboard

These stories sparked questions from readers, including one that came up repeatedly: Does a hit song today make more money than a hit did before streaming took off?

We asked this question of roughly a dozen music economists, entertainment industry bankers, and record label and streaming company executives, and they largely agreed that streaming has increased the long-term value of a hit song. However, hit songs used to drive album sales, which may have been more lucrative upfront.

It is difficult to directly compare the value of a hit song in 2024 to a hit song in 1999 — the year that record industry revenue peaked in the modern era — because the business largely moved away from issuing singles by the late 1990s. To hear a hit song, then, a fan would buy an album for as much as $18.98.

In 1999, when albums were the dominant configuration for music, 88 albums sold more than 1 million units in the U.S., according to Billboard. Albums often sold for more than their wholesale price of $12, which could mean certain older hits had a greater upfront value. However, the sources Billboard spoke with for this story all agreed that after a fan owned an album, they had little incentive to pay for that particular music again — so after about 12-18 months, the album would stop making much money.

In contrast, streaming keeps all music closer to fans’ fingertips, and hits tend to continue making money over a longer period, as opposed to a brief hype window in the album sales era.

One longtime record label executive who asked to remain anonymous estimated that a gold record in 1999 generated more than $6 million in sales, based on a wholesale price of around $12. Adjusted for inflation, that’s the equivalent of $11.3 million in 2024 dollars, according to the U.S. Federal Reserve.

In 2024, the biggest hit was Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” and Billboard estimated it generated $10.7 million from U.S. audio, video and programmed streams, digital downloads, and radio airplay spins. But due to streaming’s long tail, which has helped keep “A Bar Song” in the top five of the Billboard Hot 100, the track has continued earning significant streams in 2025: more than 140 million on-demand audio and video streams, or $192,000 in additional streaming revenue, just this year.

“[Back then], after a huge spike in revenue, a hit would have decayed over time by 60%, 70%, 80%, and eventually the song would drop to a much lower base,” says Concord CEO Bob Valentine. “Now in the streaming world, a song comes out, you get the huge pop from consumption and revenue, and because of the way algorithms keep a song in playlists and rotation, the song is much stickier. It has a higher base.”

Valentine says this is why companies like his have been able to persuade outside investors that music royalties can be securitized and sold to institutional investors like insurance companies. Concord has become the music industry’s model for raising money from such asset backed securitizations (ABS), having raised more than $5 billion to date.

While Concord is known for owning famous catalogs from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, it scored a top 10 hit in 2024 with Tommy Richman’s “Million Dollar Baby,” which Billboard estimates generated around $7.4 million.

If Concord’s catalogs are like bonds — generating consistent revenue that can be relied on for decades — hits are more like venture capital. After an initial investment, a hit can present substantial upside, Valentine says. Concord is now comfortably the fourth or fifth largest music company thanks to the strength of its publishing division and catalog, so it can afford to take risks to get more hits, which is why it’s pushing to develop its front-line business to release more songs like “Million Dollar Baby.”

The music industry globally made $41.3 billion in 2023, according to the most recent data from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) and the Confédération Internationale des Sociétés d´Auteurs et Compositeurs (CISAC).

The IFPI, which reports figures on an absolute dollar basis, not adjusted for inflation, says global recorded music revenues are at their highest level since it began tracking them in 1999.

Several sources interviewed for this story noted that, despite record-high revenues in the music industry, not everyone who contributes to making or performing a hit song makes more money today, and that many songwriters may have made more money in 1999.

For one thing, the number of songwriters credited on a hit song has increased significantly in the last decade, according to an analysis by Chris Dalla Riva in 2023. Dalla Riva found that the average number of songwriters per Hot 100 No. 1 hit rose from 1.8 during the 1970s to 5.3 in the 2010s. He noted that with interpolations, many songs credit far more songwriters: For example, Beyoncé’s Renaissance song “Alien Superstar” listed 24 songwriters.

“There is more money, we can all agree, but there are way more mouths to feed,” former Spotify chief economist and author Will Page said in an interview with the BBC in January.

Songwriters don’t just make less money because more of them work on major hits; they also make less because of the way streaming changed payouts, sources say. When the industry revolved around album sales, a songwriter on a less popular song earned the same as a songwriter on the album’s most popular song.

The rising tide effect no longer applies today because fans stream songs on a mostly a la carte basis.

Additional reporting was contributed by Ed Christman.

BMI is making a two-fold move to help music creators improve their career and lifestyle opportunities. First off, the PRO has created Spark, a program that will offer creators special discounts on music creation and technology tools while also providing educational content and health and wellness resources. Secondly, BMI will no longer charge an application […]

In a changing of the guard at one of Hollywood’s biggest talent agencies, UTA says that David Kramer will take over as CEO in June, succeeding longtime leader Jeremy Zimmer.

Zimmer, the UTA co-founder who has been CEO of the talent agency since 2012, is shifting to a role as board member and executive chairman. Paul Wachter will remain chairman of the board of UTA.

“We are thrilled to announce David as UTA’s next CEO. He is stepping into this role at an exciting time of growth, with UTA at the center of some of the most pivotal cultural moments across media, sports, and entertainment. We are confident that his leadership and client-centric approach will position the Company for continued success,” said Wachter in a statement. “I’ve known Jeremy and UTA for almost 30 years and have been impressed with Jeremy’s entrepreneurial nature and vision. It’s been remarkable how much the Company has grown and succeeded over that period. Jeremy’s years of dedicated service have left a strong and dynamic foundation for the Company’s future.”

The new role for Kramer is not completely unexpected, with the company describing the move as part of a long-planned succession process. Kramer was elevated to president of UTA in 2022.

Trending on Billboard

“These 35 years at UTA have been so incredibly rewarding,” said Zimmer in a statement. “While transition is never easy, this particular moment feels very right. David has been my chosen successor for many years and I’m certain that he will continue to uphold our great culture, support our amazing colleagues, and honor the privilege of serving our clients.”

“I am honored to be named UTA’s next CEO. We are all deeply grateful to Jeremy for his passion and dedication to this team and for helping to make UTA into one of the premier global talent agencies in the world,” Kramer added. “His vision and guidance were key to building our foundation and broadening our business to offer clients world-class capabilities across filmed entertainment, music, sports, the creator economy, and advisory services.”

Zimmer led UTA through a significant expansion period, completing some 19 acquisitions, per the company, and partnering with companies like Klutch Sports Group. UTA also secured private equity investment from EQT, in a bid to further turbocharge its growth.

In a note to staff obtained by The Hollywood Reporter, Kramer indicated that he intends to continue following that path.

“UTA has consistently taken chances, entered into new spaces, and defined categories with our work,” Kramer wrote in a memo to staff Monday. “Our focus will continue to be on nurturing and empowering that entrepreneurialism, and the unique strengths and capabilities that have allowed us to win in each category. Together, we will make sure that we foster real collaboration across our platform so that we can leverage our ability to see what’s next in culture to unlock greater opportunity for both our clients and the company as a whole.”

As for Zimmer, he will continue as executive chairman through 2025, telling employees in a note that “for the next several months I will be completely available to help transition divisions and relationships to the colleagues who will assume new responsibilities. I will also be available for lunches, laughs, and any sort of questions or concerns that I can be of help with.”

Though he added that he won’t be leaving the entertainment business entirely.

“I have been an agent for 45 years, and it’s now or never to see what else I will do. I’ve always been a builder, and I want to take the time to create something meaningful in this next chapter of my career,” he wrote. “Let’s be honest, the chances that I’m going to start an aluminum company in Alaska or a cement company in Cleveland are pretty slim. So this is not goodbye. I will remain on the board, and I will always be a friend, a supporter, and a fiercely loyal champion of this great company we’ve built together and that I love.”

You can read Kramer’s full email to UTA staff below.

TO: All Employees

FROM: DK

SUBJECT: Leadership Update

Team,

I’d like to start by saying that I am honored to be named UTA’s next CEO. We are all deeply grateful to Jeremy for his passion and dedication to this team and for helping to make UTA into one of the premier global talent agencies in the world. His vision and guidance were key to building our foundation and broadening our business to offer clients world-class capabilities across filmed entertainment, music, sports, the creator economy, and advisory services.

There is a reason that UTA has been my home for my entire career – I am incredibly fortunate to work alongside such a talented and dedicated team, and experience the impact our work has for our clients.

UTA has consistently taken chances, entered into new spaces, and defined categories with our work. Our focus will continue to be on nurturing and empowering that entrepreneurialism, and the unique strengths and capabilities that have allowed us to win in each category. Together, we will make sure that we foster real collaboration across our platform so that we can leverage our ability to see what’s next in culture to unlock greater opportunity for both our clients and the company as a whole.

UTA’s greatness isn’t just defined by the strength of our individual contributions or our ever-expanding scale; it’s our shared commitment to putting clients first and our relentless pursuit of discovering, creating and sustaining opportunity for great talent and brands. This will always be the foundation of our success and what differentiates us.

I’m excited to collaborate with each of you as we leverage the strength of the businesses we’ve built and guide this company into a new era of growth and innovation.

I look forward to spending time over the following weeks meeting with all of you and talking further about priorities ahead.

Please join me once again in thanking Jeremy for his incredible vision and leadership. And thank you for all you do to make UTA the company it is today.

Regards,

DK

This story was originally published by The Hollywood Reporter.

Austin’s annual SXSW conference and festival is set to scale back its 2026 edition. Next year, the event will run from March 12-18 — two days shorter than this year’s event — with its interactive, film/TV and music programs running concurrently. The news was first reported by the Austin American-Statesman. “A shorter SX gives attendees […]

Music fans are amping up for 2025 to be the biggest year ever in stadium touring and leading the pack is Beyoncé, whose Cowboy Carter Tour has posted impressive sales after a month of ticket availability. The “Texas Hold ’Em” singer initially faced significant criticism when early presales revealed aggressive ticket prices for the now-31-date stadium tour through nine major markets — L.A., Chicago, New York, London, Paris, Houston, Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Las Vegas.

Some fans criticized Bey’s high prices — tickets in her stageside Club Ho-Down section cost $1,795 a piece — but they also bought a lot of tickets. Beyoncé sold more than 1 million tickets during the fan and sponsor presales and today two-thirds of the stops on the tour — all of the dates in Houston, Atlanta, Washington D.C. and Chicago and three of her five nights in New York — are effectively sold out, with Live Nation announcing that 94% of all tickets have already been sold.

Trending on Billboard

The Cowboy Carter Tour likely won’t outgross her 2023 Renaissance Tour — which ran 55 dates compared to 30 for Cowboy Carter — but she will earn far more on average than Renaissance thanks to higher ticket prices. It’s an impressive feat considering the number of A-list stadium tours competing for fan dollars this summer, including Kendrick Lamar, Post Malone, Shakira, The Weeknd and BlackPink.

The Beyoncé tour’s economic prowess is derived from its high ticket prices, priced to match what scalpers would sell the tickets for on the secondary market. Fans got their first glimpse of ticket prices on Feb. 11 for the Beyhive presale, the first of a handful of ticket presales for Beyoncé. Fans were required to register in advance for the presale and then wait to receive an email notifying them when it was their turn to try and purchase tickets for the high-demand outing.

Once the sale opened, they were given access to a wide range of tickets and prices, with nosebleeds as low as $102 while floor seats and tickets inside Beyoncé’s standing-room fan areas starting at $877 and rising to several thousand dollars per seat.

For example, tickets in the 500s section at SoFi Stadium in the upper seating area were among the least expensive for Los Angeles, priced at $166 apiece, while tickets on the floor started at $878 per ticket. The most expensive tickets at SoFi Stadium were priced at $1,422 for floor seats, while many floor tickets were priced between $1,000 to $1,200.

The tickets were aggressively priced — according to Billboard’s own non-weighted analysis, the average ticket price during the presale was $670 per ticket. The range in pricing also did cause some confusion among fans, many of whom accused Ticketmaster of using surge-pricing tactics during the ticket sale process, a practice the company denies. While Ticketmaster uses algorithms to help set prices ahead of a ticket sale, it does not adjust prices after they go on sale nor does it engage in surge pricing during periods of high demand.

While fans claimed to have seen prices change, what likely happened was that fans were comparing price points across multiple sections and seeing large variations in prices in seating sections that appeared close to one another. For example, tickets on the 100 level for Beyoncé’s June 28-29 shows in Houston saw large swings in price — the 138 section had tickets priced at $455, while just four sections over in 134, tickets were priced at $565. Closer to the stage, prices in section 102 were at $636 while tickets in section 108 were $852.

That variation in price across multiple sections confused fans who logged into the presale and had limited time to comparison shop. Adding to the confusion was that some of the least expensive tickets were first to sell during the presale, creating the perception that tickets were getting more expensive and the price was increasing, as the minutes of the presale ticked away.

Those high prices have remained strong on the secondary market, according to an analysis by Billboard. Typically, prices on the secondary market drop slightly below face value after a massive stadium onsale, but by only scheduling 30 concerts this summer, Beyoncé has created sustained demand for tickets that extended past the presale and general onsale. Tickets for her two Houston concerts, her three in Chicago concerts and two Washington, D.C. shows are effectively sold out, with only a handful of high-priced floor tickets for purchase on the primary market, while plenty of tickets are listed from secondary sellers for close to face-value prices.

Most impressive, Beyoncé has nearly sold out her first three concerts in New York (May 22, 24 & 25) and is closing in on selling out the final two concerts (May 28 & 29). Fans still hoping to score tickets will probably have the most success in Los Angeles at one her five concerts at SoFi Stadium (April 28, May 1, 4, 7 and 9).

Plenty of tickets are still available on the 500 level for as low as $105, as well as 300 level marked as VIP selling starting at $305, floor seats starting at $535 and tickets next to the stage inside the standing room only Sweet Honey and Buckin’ Honey pits.

Audacy has announced a slate of executive changes, with Kelli Turner appointed as president and CEO, while Chris Oliviero has been named chief business officer, and Bob Philips named as chief revenue officer.

Turner had been serving as interim president and CEO since January, after former Audacy chief David Field stepped down, and has served on the Audacy board since September 2024. Turner most recently served as managing director and CFO for Sun Capital Partners, and previously served as president and COO for Blackstone-owned music licensing and rights management SESAC Holdings. She has also served in various executive and leadership roles in the investment and media industries, including RSL Group, Martha Stewart Living, Time Warner, Allen & Company and Citigroup.

Oliviero was most recently market president for Audacy New York, and Philips was president of Audacy Networks and multi-market sales.

Trending on Billboard

“On behalf of the Audacy board, we are delighted that Kelli Turner has agreed to take on the permanent President and CEO role and lead Audacy through its next phase of reinvention and growth,” Michael Del Nin, chairman of Audacy, said in a statement. “She is an exceptional media executive who, along with Chris Oliviero and the rest of the Audacy team, will ensure we continue to invest in high-quality content to engage our audiences and provide best-in-class solutions to our partners.”

“It’s a privilege to lead Audacy at this exciting moment in its impressive history and the evolution of audio,” Turner added. “This is one of the most dynamic businesses in media and entertainment, and I am looking forward to partnering with Chris Oliviero and all of our teams to build on our momentum with audiences, creators and advertisers. I’m especially excited by the appointments of Chris and Bob, who know Audacy’s businesses inside out and whose track records in management, programming and sales are second to none.”

Oliviero has served as market president in New York since 2020 and previously spent over 23 years at CBS Radio (which became part of Audacy in 2017). Philips joined CBS Radio in 1996 and later took on the role of CRO for CBS Radio and Entercom. After Entercom’s rebranded as Audacy in 2021, Philips transitioned into his most recent role.

Audacy has also announced several departures, including COO Susan Larkin, chief digital officer J.D. Crowley, chief marketing officer Paul Suchman and executive vp and general counsel Andrew Sutor.

Mike Dash, who has been with Audacy’s companies for nearly 20 years, has been named executive vp and general counsel, and will succeed Sutor, who will stay on for a transition period.

Universal Music Group has filed a scathing first court response to Drake’s defamation lawsuit over Kendrick Lamar’s diss track “Not Like Us,” blasting the case as “no more than Drake’s attempt to save face” after losing a rap beef.

In a motion filed Monday (March 17) seeking to dismiss the lawsuit, attorneys for the music giant argued that Drake’s allegations against the company were clearly “meritless” — and that he had gone to court simply because he had been publicly embarrassed.

“Plaintiff, one of the most successful recording artists of all time, lost a rap battle that he provoked and in which he willingly participated,” UMG’s lawyers write. “Instead of accepting the loss like the unbothered rap artist he often claims to be, he has sued his own record label in a misguided attempt to salve his wounds.”

Trending on Billboard

In the filing, UMG pointedly noted that Drake himself had leveled his own “hyperbolic insults” and “vitriolic allegations” during the same exchange of stinging rap tracks, including accusing Lamar of domestic abuse and questioning whether the rival had really fathered his son.

“Drake has been pleased to use UMG’s platform to promote tracks leveling similarly incendiary attacks at Lamar,” the company’s attorneys write. “But now, after losing the rap battle, Drake claims that ‘Not Like Us’ is defamatory. It is not.”

In a statement to Billboard on Monday, Drake’s attorney Michael J. Gottlieb responded to the new filing. “UMG wants to pretend that this is about a rap battle in order to distract its shareholders, artists and the public from a simple truth: a greedy company is finally being held responsible for profiting from dangerous misinformation that has already resulted in multiple acts of violence,” Gottlieb said. “This motion is a desperate ploy by UMG to avoid accountability, but we have every confidence that this case will proceed and continue to uncover UMG’s long history of endangering, abusing and taking advantage of its artists.”

Lamar released “Not Like Us” last May amid a high-profile beef with Drake that saw the two stars release a series of bruising diss tracks. The song, a knockout punch that blasted Drake as a “certified pedophile” over an infectious beat, eventually became a chart-topping hit in its own right and was the centerpiece of Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show.

In January, Drake took the unusual step of suing UMG over the song, claiming the label had defamed him by boosting the track’s popularity. The lawsuit, which doesn’t name Lamar himself as a defendant, alleges that UMG “waged a campaign” against its own artist to spread a “malicious narrative” about pedophilia that it knew to be false.

But in Monday’s response, UMG says the lyrics to Lamar’s song are clearly the kind of free speech that are shielded from defamation lawsuits by the First Amendment. The song contains over-the-top insults, the company argued, but so do all such tracks, including those by Drake.

“Diss tracks are a popular and celebrated artform centered around outrageous insults, and they would be severely chilled if Drake’s suit were permitted to proceed,” the company wrote. “Hyperbolic and metaphorical language is par for the course in diss tracks — indeed, Drake’s own diss tracks employed imagery at least as violent.”

In technical terms, UMG is arguing that Lamar’s lyrics are either “rhetorical hyperbole” or opinion — the kind of statements that might sound bad but cannot actually be proven false. Since defamation only covers false assertions of fact, statements of hyperbole and opinion can’t form the basis for such lawsuits.

To make that point, UMG cites Drake’s own public support for a 2022 petition criticizing prosecutors for using rap lyrics as evidence in criminal cases. That letter, also signed by Megan Thee Stallion, 21 Savage and many other stars, criticized prosecutors for treating lyrics as literal statements of fact.

“As Drake recognized, when it comes to rap, ‘the final work is a product of the artist’s vision and imagination’,” UMG’s lawyers write. “Drake was right then and is wrong now. The complaint’s unjustified claims against UMG are no more than Drake’s attempt to save face for his unsuccessful rap battle with Lamar. The court should grant UMG’s motion and dismiss the complaint with prejudice.”

Drake’s attorneys will file a court response to UMG’s motion in the weeks ahead, and the judge will rule on the motion at some point in the next few months. If denied, the case will move ahead into discovery and toward an eventual trial.

When Island/Republic/MCA Nashville released Chappell Roan’s “The Giver” on March 12, the move extended a pop/country crossover trend that has seen the likes of Shaboozey, Beyoncè and Post Malone successfully hop genre fences.

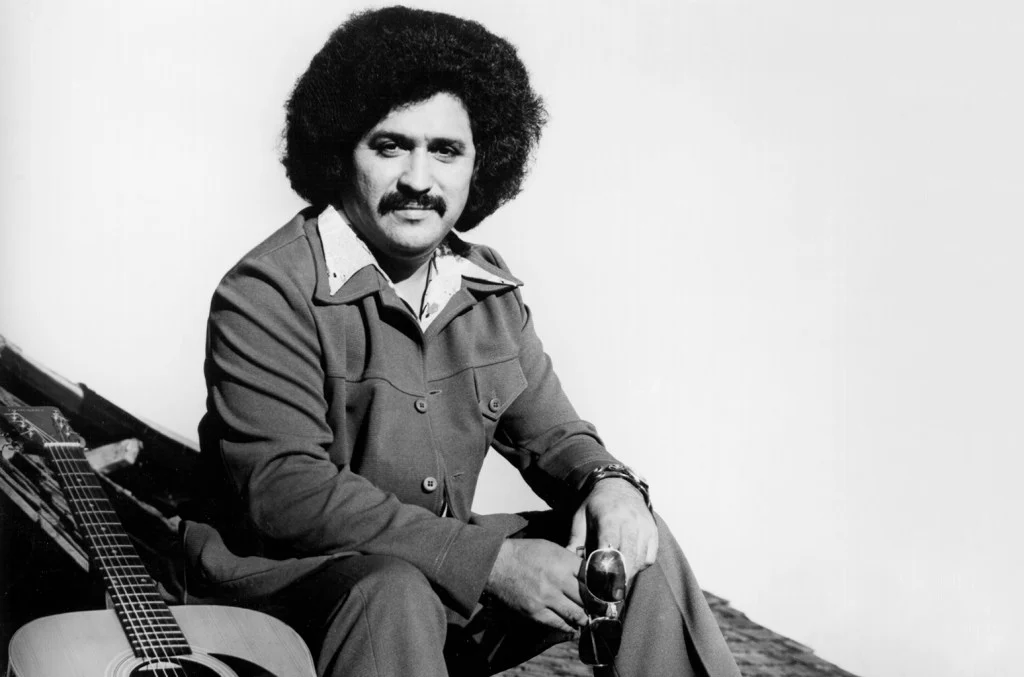

As current as the development may be, it’s also a case of history repeating. The release comes 50 years after Freddy Fender’s “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” reigned on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart dated March 15. “Teardrop” went on to top the Billboard Hot 100 on May 31, 1975, in the midst of a crossover wave.

“That song just caught fire,” says Country Music Hall of Fame member Joe Galante, who handled marketing for RCA Nashville at the time. “It sold, and that was one thing that made it difficult for people to walk away from, was the sales numbers. Even as a competitor, I was sitting there going, ‘How the hell is this happening?’ And you start looking at the numbers and you went, ‘Well, that’s how it’s happening.’ ”

Trending on Billboard

Fender’s success was not an isolated example in 1975. From March 8 through June 7 that year, four different singles reached the Hot 100 summit while simultaneously becoming country hits: Fender’s “Teardrop,” Olivia Newton-John’s “Have You Never Been Mellow,” B.J. Thomas’ “(Hey Won’t You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song” and John Denver’s“Thank God I’m a Country Boy.”

When Fender was at No. 1, at least seven more titles on that same country chart made significant inroads on the Hot 100 and/or the Easy Listening chart (a predecessor of adult contemporary), including Jessi Colter’s “I’m Not Lisa,” Elvis Presley’s “My Boy” and Charlie Rich’s “My Elusive Dreams.” Additionally, Linda Ronstadt peaked at No. 2 on country with the Hank Williams song “I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still in Love With You),” weeks ahead of the crossover follow-up “When Will I Be Loved.”

Throughout the rest of 1975, the country crossover trend continued with Newton-John’s “Please Mister Please,” Fender’s “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights,” Glen Campbell’s “Rhinestone Cowboy,” The Eagles’ “Lyin’ Eyes,” Tanya Tucker’s “Lizzie and the Rainman” and C.W. McCall’s “Convoy.”

Then, as now, plenty of fans and critics debated if some of those titles belonged on the country station.

“For me, the answer to ‘What is country?’ is: the records that the country audience, at that time, thinks belong on a country radio station,” says Ed Salamon, a Country Radio Hall of Fame member who became PD in 1975 of WHN New York.

Salamon programmed plenty of crossover music, sometimes incorporating songs that weren’t being promoted to the station, in an effort to appeal to a metro audience that didn’t have much history with the genre.

WHN became a major success story — just five years later, the Big Apple got a second country radio station — but its crossover mix yielded as much hostility from Nashville as praise. Part of that was directly related to the corporate source of some of the records on the playlist: Denver, Newton-John and The Eagles were all signed out of New York or Los Angeles.

“There was such a pushback about what I did that I didn’t fully comprehend it at that time,” Salamon reflects. “I was taking the space that the Nashville label thought should go to one of their records on a country radio station, and I was giving it to the pop division.”

Exactly one year after Fender topped the country chart, crossover material in 1976 had subsided. The number of crossover singles was the same, but none of them had the same level of impact.

“It’s the luck of the draw,” says Country Radio Hall of Fame member Joel Raab, a consultant and former programmer for WHK Cleveland.

Two of those 1976 crossovers, Cledus Maggard’s “The White Knight” and Larry Groce’s “Junk Food Junkie,” were novelty records, distinguishing them from the 1975 batch.

“We’d seen success in the crossover the year before,” recalls Country Radio Hall of Fame member Barry Mardit, whose programming history included WEEP Pittsburgh and WWWW Detroit. “If those songs weren’t consistently coming, we were therefore looking for something else that would grab the ear, that would grab the attention of the listener, like a novelty song does.”

Crossover records would continue through the rest of the ’70s, with Crystal Gayle, Dolly Parton, Ronnie Milsap, Kenny Rogers, Eddie Rabbitt and a couple of Waylon Jennings & Willie Nelson duets benefiting. In most cases, those happened when one or more label executives were enthusiastic enough to take a risk. Record companies had to be judicious since radio stations relied heavily on local sales reports for research.

“You had to have product in stores in order for people to do sales checks,” Galante notes. “So it wasn’t as simple as just saying, ‘Oh, I think I’ll go do this.’ You’ve got to get the goods in stores, and if it didn’t move and they [were returned], you got a double whammy. And you’d spent the money. So you were careful about your shots, and you didn’t go willy-nilly trying to cross over a record.”

Similarly, artists often err when they purposely attempt to cross over. It’s an issue that country learned the hard way in the aftermath of the 1980 Urban Cowboy soundtrack.

“The Urban Cowboy sound was a moment,” Raab says. “It wasn’t a trend. It was just a bunch of really good hit songs that went with a movie — and those songs, by the way, were all pretty country: [Johnny Lee’s] ‘Looking for Love’ and [Mickey Gilley’s]‘Stand by Me.’ These were just really good country records. And because the movie was so popular, [some artists] said, ‘Oh, you know, I’ll be more pop.’ And they made these really bad pop-sounding records in the early to mid-’80s.”

The 2025 version of crossover is a little different — streaming data has helped identify the songs that work across formats, influencing the trajectory for music by Morgan Wallen, Ella Langley & Riley Green, Marshmello & Kane Brown, HARDY, Jelly Roll and Dasha.

Artists are interacting more freely across genre, with pairings of Kelsea Ballerini & Noah Kahan, Thomas Rhett & Teddy Swims and Post Malone & Wallen all on the current Hot Country Songs chart. And, Galante points out, country acts are playing stadiums and arenas in major markets, unlike in the ’70s, when they were mostly in small theaters in midsize metros.

As a result, there’s less incentive for country artists to refashion their music in a play for pop success.

“Country is just so big in its own right,” Mardit says, “that they don’t need to do that.”

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio