universal music group

Page: 2

Mexican music powerhouse Fonovisa-Disa is rebranding as Fono, it was announced on Wednesday (May 14).

The new name for the regional Mexican label, which is part of Universal Music Group, comes more than 40 years after its launch. It went on to become a pioneering company at a time when música mexicana didn’t have the global spotlight it has today.

“This isn’t the end of an era, at least we don’t feel like it is,” Antonio Silva, Fono’s U.S.-Mexico MD and a towering figure at the company, tells Billboard. “This is an evolution of Fonovisa, of our team, our artists, and it is an evolution designed to expand our genre and culture. This rebranding does not make Fonovisa’s legacy disappear, we intend to make [the genre] more relevant and take it beyond where our artists have already taken it.”

Fono is home to genre giants Alejandro Fernández, Los Tigres del Norte and Banda El Recodo, to name a few of the veterans on its roster, as well as emerging acts such as Camila Fernández, Danny Felix and Majo Aguilar — a reflection of the genre’s multigenerational audience. The label’s rebranding comes at a time when regional Mexican music has grown significantly in popularity and exposure over the past few years. Still, there’s much more opportunity for growth, says Alfredo Delgadillo, president/CEO of Universal Music México.

“Mexican music is in a good place right now, but we want to see it go further,” says Delgadillo, who notes the rebranding has been in the works for over a year. “It’s important to note that while corridos are getting all the attention at this moment, the rest of the subgenres like banda, norteño, mariachi, cumbia, continue to have enormous relevance, and we don’t want that to get lost. We see a very strong opportunity. The focus on the corrido, which is very important and, coming from what Fonovisa is and what it has built, we don’t want it to end or stay there. For us, the cultural richness of the entire genre goes beyond a special moment for just one of the subgenres.”

Trending on Billboard

Fono will continue building on the legacy that Fonovisa-Disa built. Previously an indie label, Fonovisa was acquired by Universal in 2008 and became an institution in the regional Mexican music space. “We saw this as [an opportunity] to grow, to take Mexican music and all its genres to other regions and territories,” says Ana Martínez, who was appointed Fono’s U.S. GM last year. “Our vision is focused on the opportunity to take our culture to other audiences, above all in a sustainable way, helping develop something that lasts more than the isolated impact that sometimes happens.”

Adds Silva, “After so many years of working in the music industry and practically all dedicated to regional Mexican, I’ve experienced the phenomenon of Bronco, Rigo Tovar and so many more that have been a part of our history. Now, to reach this moment where the company has this vision of expanding our culture and all that we are, I’m thankful to Fono and Universal for giving us a new road to navigate the world.”

Chinese streaming platform Tencent Music Entertainment grew its stake in the world’s largest music company, Universal Music Group (UMG), by picking up a direct 2% equity holding worth $327 million in March, the company said on Tuesday (May 13).

While it did not identify the seller — described in Tuesday’s filings only as “one of our associates” — Pershing Square sold 50 million shares of UMG on March 13, raising about $1.3 billion, according to filings and research reports. Tencent Music and Pershing Square did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The news means that Tencent Music and UMG each own notable stakes in each other’s companies, as UMG owns a 0.79% stake in TME as of Dec. 31 that’s currently worth $181.2 million.

Trending on Billboard

Tencent Music has been an investor in UMG since March 2020, when it joined a consortium of investors led by its parent company, Tencent Holdings. That consortium accumulated a 20% stake in UMG from UMG’s parent company, Vivendi S.A., between 2020 and 2021, of which Tencent Music owned a 10% share, according to filings.

This March, that consortium “completed a transfer of the UMG shares held by the consortium to its members,” which resulted in Tencent Music acquiring a direct 2% equity interest in UMG, according to its annual report.

Tencent Music, which reported first-quarter revenue of 7.36 billion Chinese yuan ($1.01 billion) on Tuesday, recognized “other gains” worth 2.44 billion Chinese yuan (US$336 million), of which the UMG stock comprised 2.37 billion Chinese yuan (US$327 million), according to filings.

Pershing Square has been an investor in UMG since 2021, and though the mid-March stock sale reduced its stake in UMG to 4.9% from 7.6%, the music company remains the hedge fund’s largest single holding, comprising 17% of its capital.

The sale came ahead of Pershing Square’s plan to register its UMG shares in the United States in September. Pershing Square head and UMG board member Bill Ackman has advocated for the company to move its primary listing from the Euronext Amsterdam stock exchange to a U.S.-based exchange, saying it would add value for the company.

Five years ago, fitness companies looked like the next big thing for music rights owners as the onset of the COVID-19 lockdown turned Peloton, the maker of high-tech stationary bicycles and treadmills, into a household name and the leader in a suddenly hot connected fitness market.

Peloton’s founder, John Foley, had created an online version of music-driven, brick-and-mortar studios such as SoulCycle. Unlike the staid strength and cardio products of earlier years, the new breed of bikes and treadmills manufactured by the company were internet-ready and could stream live or pre-recorded workouts. Other startups took notice, with competitors like Tonal and Hydrow vying for market share.

“There were fitness companies who saw what Peloton was doing, which was really putting music at the center of their workouts,” says Vickie Nauman, a licensing expert and founder/CEO of CrossBorderWorks. Instructors, some of whom would become small-time celebrities, used music to create identities and build communities. “This was the original founder’s vision,” she says.

Trending on Billboard

Flush with investment capital, fitness companies followed Peloton into expensive licensing agreements with rights holders to infuse music into their at-home products. Royalties from connected fitness companies, as well as social media and other new revenue streams, went from about 3% of the average catalog’s revenue in 2021 to “something like 7%” in 2023, according to Jake Devries, a director in Citrin Cooperman’s music and entertainment valuation services practice.

As it turned out, 2020 and 2021 were peak at-home fitness. The financial impact of the post-pandemic fitness bubble was seen in Universal Music Group’s results for the fourth quarter of 2024: A decline in its fitness business accounted for a nearly one percentage-point decline in its subscription growth rate, equal to approximately $12.5 million. And during its most recent earnings call on April 29, the company noted that fitness revenue was flat in the first quarter.

After pandemic restrictions ended, the stay-at-home fitness business ran into competition from gyms and fitness studios as people returned to public life. As a result, according to numerous people who spoke with Billboard, connected fitness companies had less cash to put into music licensing and, realizing they didn’t need massive catalogs and didn’t have the expertise to properly manage the rights and issue royalty payments, looked for more affordable, less arduous options.

Peloton, founded in 2012, was a trailblazer in at-home fitness. Its studio-quality bikes, which currently cost between $1,445 and $2,495, are outfitted with touchscreens that stream live and on-demand content for an additional $44 per month. Music is a focal point for the online classes, just as brick-and-mortar studios like SoulCycle incorporate popular songs into their workouts. Despite the high prices of Peloton’s bikes, online content has a greater financial impact: In its latest fiscal year, subscriptions accounted for 63% of the company’s $2.7 billion of revenue and 96% of its $1.2 billion of gross profit.

Music enhances online workouts in the same way it makes going to a fitness studio or a gym more enjoyable. But building cycle workouts around setlists of specific songs isn’t straightforward. Unlike brick-and-mortar locations that require only blanket licenses from performance rights organizations such as ASCAP and BMI, Peloton required more expensive direct licenses to incorporate music into its streaming content. After being sued by music publishers for copyright infringement in 2019, Peloton settled the following year and began negotiating the proper licenses.

Such a license had never been done for a fitness company, so major labels and publishers modeled custom licenses for Peloton based on their deals with Spotify and other on-demand music platforms, according to a licensing executive familiar with the negotiations. The agreements called for Peloton to pay rights holders based on a monthly per-subscriber fee, and the pool of royalties would then be proportionally divided based on usage, according to this person.

Peloton had built a name for itself in the fitness community by 2019, but it was supercharged the following year by the COVID-19 pandemic. As people stayed away from public places such as gyms and fitness studios, Peloton’s revenue jumped from $384 million in fiscal 2019 to $1.45 billion two years later, and its share price climbed from $27 following its September 2019 initial public offering to $171 in January 2021.

The enthusiasm for at-home fitness also benefited Peloton’s competitors. Hydrow, which offers rowing machines with Peloton-like streaming content, raised $25 million in June 2020 and another $55 million in March 2022. Tonal, a connected strength training platform, had raised a total of $90 million by 2019, before the pandemic piqued interest, then raised $110 million in September 2020 and $380 million in two funding rounds in 2021 and 2023 — the latter at a lower valuation.

As other connected fitness companies quickly sought music licenses to replicate Peloton’s success, rights holders offered them a version of the Peloton license, which provided them rights to large catalogs. (Peloton, the lone publicly traded company of the bunch, revealed in its 2021 annual report that it had a catalog of 2.6 million tracks.) “Once there was a model, it was always going to be easier to replicate a model you think is working than create a new licensing deal,” says the licensing executive.

But these fitness startups, desperate to corner share in a fast-growing market, initially made some missteps. “Because it was such a race, I think that many online fitness companies saw this as an existential opportunity, and they did not take the time to investigate what they were getting into,” says Nauman. “And so, they licensed all of this music, and that sent a signal to rights holders all over the world that fitness was going to be an enormous new line of business.”

The Peloton-style licenses weren’t cheap. Record labels and publishers were “aggressive with the rates they were asking for a lot of the services,” says an attorney familiar with the terms of the licensing contracts. An app-based product would likely pay 30% of revenue to music rights holders, according to this person, while hardware-based products with higher overhead and costs would pay approximately 16% of revenue. “That’s a pretty big share of revenue for a company that is not a music company,” the attorney adds.

The Peloton-style sync licenses also came with more complexity than fitness companies could handle. Managing a music catalog requires technology and know-how that fitness companies don’t have. They needed help matching compositions to sound recordings to ensure licenses were acquired from all rights holders, and the reporting required for PROs and making direct payments to record labels and publishers were outside of the fitness companies’ expertise.

As fitness companies dealt with stagnant growth, they laid off staff and tightened their budgets. From February 2022 to May 2024, founder/CEOs at Peloton, Tonal and Hydrow were forced out. When Peloton replaced Foley with former Spotify CFO Barry McCarthy in February 2022 and announced plans to lay off 20% of its corporate staff, its share price was trading under $30, down more than 82% from its high mark just 13 months earlier. Tonal and Hydrow each laid off about 35% of their workforces in 2022, and Hydrow further thinned its staff in 2023.

Sync licenses are crucial to Peloton because classes are often built around playlists, and music is crucial to the indoor cycling experience. But not every connected fitness product needs to integrate music in a way that requires a more expensive, Peloton-style license. For many other companies, a non-interactive, DMCA-compliant radio service with pre-cleared music is more than adequate.

Constrained by tighter budgets, some connected fitness companies started looking for alternatives to their original licenses. Today’s connected fitness CEOs tend to be most concerned about the cost and complexity of music licensing and the likelihood of being sued, says Jeff Yasuda, founder/CEO of Feed.fm, a provider of licensed music to connected fitness companies such as Hydrow, Tonal, Future and Ergatta. Being able to use popular music in their apps isn’t a priority.

“For a fitness company, your job is to make the best jumping jack app on the planet,” says Yasuda. Making a mistake handling music rights would put a company in jeopardy of facing lawsuits brought by music rights holders. “It’s just not worth the risk,” he says.

Feed.fm assures clients that the rights are compatible with various laws in different countries. It provides pre-cleared catalogs from Sony Music, Warner Music Group, Merlin, Insomniac Music Group and A Train Entertainment, and it works with record labels to create thematic stations, including one curated by CYRIL, a recording artist for Warner-owned Spinnin’ Records, and a Brat-inspired station featuring Charlie xcx, Dua Lipa, Chappell Roan and other artists that represent the brat summer of 2024. A rights holder itself, Feed.fm has signed 40 to 50 artists, which its vp of music affairs, Bryn Boughton, says gives it greater flexibility in licensing.

Outsourcing the licensing ultimately saves fitness companies money, says Con Raso, co-founder/managing director of Australia-based Tuned Global. Raso’s pitch to fitness companies is to invest money in marketing and let companies like Tuned Global handle the technology. “We don’t think, unless you’re doing it on a massive scale, you’re going to save money,” he says. Raso estimates that Tuned Global can remove 70% of clients’ costs versus licensing music and managing rights themselves.

Beyond traditional fitness apps, there’s big potential for licensing ambient or mood music for a new wave of mental health-focused apps. In the last six months, Raso has seen an uptick in demand for licensed music from companies more broadly associated with health and medical care. Consumers have a wide choice of apps for yoga, meditation, mindfulness and sleeping that incorporate music. Led by companies such as Calm, the market for spiritual wellness apps hit $2.16 billion in 2024, according to Researchandmarkets.com, and will grow nearly 15% annually to $4.84 billion by 2030. Record labels have already made forays into this space. Universal Music Group, for example, formed a partnership in 2021 with MedRhythms, which uses software and music to restore functions lost to neurological disease or injury.

The COVID-era boom of connected fitness products, though, seems all but over, having failed to live up to lofty expectations. Chalk it up to the chaotic nature of the pandemic and fast-moving startups battling for market share, says Nauman. “I don’t think it’s anybody’s fault,” she says. “I think it was such a lightning-in-a-bottle time that they were in a race to get to market as fast as they possibly could.”

Additional reporting by Liz Dilts Marshall.

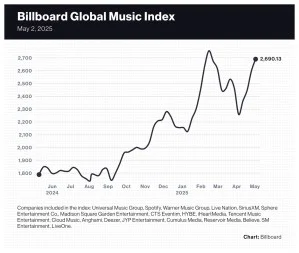

Though economic uncertainty lingers, some music companies’ stocks got boosts following their first quarter earnings releases this week, while a better-than-expected jobs report on Friday (May 2) lifted stocks across the board.

K-pop companies were among the top performers of the week. Led by HYBE’s 13.8% gain following its first quarter earnings report on Tuesday (April 29), the four South Korean companies had an average share price gain of 10.3%. JYP Entertainment rose 11.7% and SM Entertainment, which announces earnings on Wednesday (May 7), improved 9.0%. YG Entertainment gained 6.6%.

The 20-company Billboard Global Music Index (BGMI) rose 3.6% to 2,690.13, its fourth consecutive weekly improvement. At 2,690.13, the BGMI has improved 19.1% since a two-week slide and stands just 2.4% below its all-time high of 2,755.53 set during the week ended Feb. 14.

Trending on Billboard

Music stocks slightly outperformed the Nasdaq and S&P 500, which rose 3.4% and 3.1%, respectively. Foreign markets were mostly positive but more subdued. The U.K.’s FTSE 100 rose 2.2%. South Korea’s KOSPI composite index gained 0.5%. China’s SSE Composite Index lost 0.5%.

Universal Music Group (UMG) gained 4.3% to 25.86 euros ($29.23) following a quarterly earnings report showing that recorded music subscription revenue grew 11.5% and overall revenue improved 11.8%. JP Morgan analysts’ conviction on UMG “remains very high,” and the strong quarter “should help rebuild confidence and share price momentum” dented by Pershing Square’s sale of $1.5 billion in UMG shares, analysts wrote in an investor note on Tuesday.

Spotify finished the week up 3.7% to $643.73 despite its shares dropping 3.4% on Tuesday after the company’s first-quarter earnings report included guidance on second-quarter subscription additions that seemed to underwhelm investors. Gross margin of 31.6% beat Spotify’s 31.5% guidance. Loop Capital raised Spotify to $550 from $435, while Barclays lowered it to $650 from $710. UBS maintained its $680 price target and “buy” rating. Guggenheim maintained its “buy” rating and $675 price target.

Live Nation, which reported first quarter earnings on Thursday (May 1) and predicted a “historic” 2025, gained 2.3% on Friday and finished the week up 0.7%. A slew of analysts updated their price targets on Friday. Two were upward revisions: Jefferies (from $150 to $160) and Wolfe Research (from $158 to $160). Two were downward revisions: Rosenblatt (from $174 to $170) and JP Morgan (from $165 to $170).

Nearly all streaming stocks posted gains. LiveOne was the week’s top performer, jumping 18.0% to $0.72. Chinese music streaming companies Cloud Music and Tencent Music Entertainment gained 11.6% and 7.1%, respectively. French music streamer Deezer gained 1.4% to 1.44 euros ($1.63) after the company’s first-quarter earnings on Tuesday. Abu Dhabi-based Anghami fell 3.1% to $0.62.

Cumulus Media fell 33.% to $0.14. Most of the decline came on Friday as the stock ceased trading on the Nasdaq and began trading over the counter.

Created with Datawrapper

Created with Datawrapper

Created with Datawrapper

According to Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino during the company’s earnings call on Thursday (May 1), every chief executive is being asked the same question this earnings season: Are you feeling a consumer pullback?

It’s a reasonable query given the worsening state of the economy. U.S. gross domestic product decreased at an annual rate of 0.3%, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis announced on Tuesday (April 30). And on Thursday, news broke that U.S. joblessness claims for the week ended April 26 surged beyond expectations. Earlier in April, the University of Michigan reported that its consumer sentiment score fell to 57.0 in March, down from 71.8 in November. That puts the closely watched measure on par with scores during the 2009 fallout of the U.S. housing crisis and in August 2011, as consumers feared a stalled recovery.

But on Friday (May 2), a reprieve from the bad news arrived in the form of a better-than-expected jobs report. And judging from comments during this week’s earnings calls, many music companies remain confident that their businesses will weather whatever storms develop in 2025.

Trending on Billboard

“We haven’t felt [a pullback] at all yet,” Rapino said. Whether it’s a festival on-sale, a new tour or a standalone concert, Live Nation has seen “complete sell-through” and “strong demand” that surpasses 2024’s record numbers, he added: “So, we haven’t seen a consumer pullback in any genre, club, theater, stadium [or] amphitheater.”

To see how Live Nation fared during the last recession, you’d have to go back to 2009. The U.S. housing crisis had shaken the economy and GDP shrank 2.0% that year, but Live Nation’s revenue increased 2.3%. Then, as the economy rebounded in 2010, the company’s revenue jumped 21.1% in 2011.

Of course, live music took a nosedive during the pandemic, but the drop-off in 2020 and 2021 was caused by a decrease in the supply of concerts, not a dip in demand for live music. When artists returned to touring, fans showed up in record numbers.

Some parts of the economy can be trusted to stumble during a downturn. Case in point: U.S. advertising revenue fell 14.6% in 2009 and dipped 5.4% in 2020. Brands are quick to cut their ad spending when they anticipate a pending sales decline. For example, car dealerships frequently advertise on TV and radio, but cut back as auto sales fell 17.6% in 2009 and 20.3% in 2020.

A decline in advertising is harmful to some parts of the music business. Radio companies have struggled with weak ad revenues in recent years, and their stock prices have taken a beating. Through Friday, iHeartMedia’s stock price is down 50% year to date, and Cumulus Media, which de-listed from the Nasdaq today, has lost 82%.

But music is a “counter-cyclical” business, meaning it doesn’t follow larger economic trends, and the popularity of subscriptions has helped insulate the music industry from economic woes. It’s widely believed that consumers simply won’t part with their favorite music service. In fact, $11.99 for a month from Spotify or Apple Music, although a few dollars higher than two years ago, is considered by top music executives to be underpriced.

During Spotify’s earnings call on Tuesday, CEO Daniel Ek said “engagement remains high, retention is strong” and the ad-supported free tier gives users a way to remain at Spotify “even when things feel more uncertain” — not that Ek is uncertain about the company’s future. “I don’t see anything in our business right now that gives me any pause for concern,” he said flatly.

Universal Music Group (UMG) is on the same page as Ek. CEO Lucian Grainge attempted to ease investors’ concerns by explaining that he has witnessed music weather numerous recessions. “Music has always proven to be incredibly resilient,” he said during an earnings call on Tuesday. “It’s low cost, high engagement and obviously a unique form of entertainment.” In addition, added chief digital officer Michael Nash, UMG’s licensing agreements include minimum guarantees that provide “very significant protection against digital revenue downside risk this year.”

There’s always a chance that unforeseen events or a particular confluence of factors will ruin music’s winning streak. With subscription prices rising, a possible “superfan” subscription tier on the horizon, ticketing prices not getting any cheaper and tariffs increasing the costs of music merchandise, consumers may reach a breaking point. MIDiA Research’s Mark Mulligan argued this week that superfans are being “pushed to the limit” and concertgoers don’t have an unlimited ability to absorb higher ticket prices.

So far, however, the evidence suggests music fans’ spending is continuing unabated. Live Nation says its various metrics — ticket sales, deferred revenue for future concerts — point to another “historic” year in 2025. Rapino added that the company’s clubs and theaters haven’t reported a decrease in on-site spending. Part of that could be that Live Nation carefully curates an array of food and beverage options that maximize per-head revenue. But a more likely explanation is that people need entertainment now more than ever.

While many public companies are struggling amid the backdrop of macroeconomic uncertainty and the looming threat of global tariffs, music company executives are beating the drum for music as a stable place to invest. Despite a plateauing of the growth curve, revenue from streaming subscriptions continues to drive relative stability at Spotify, Unversal Music Group […]

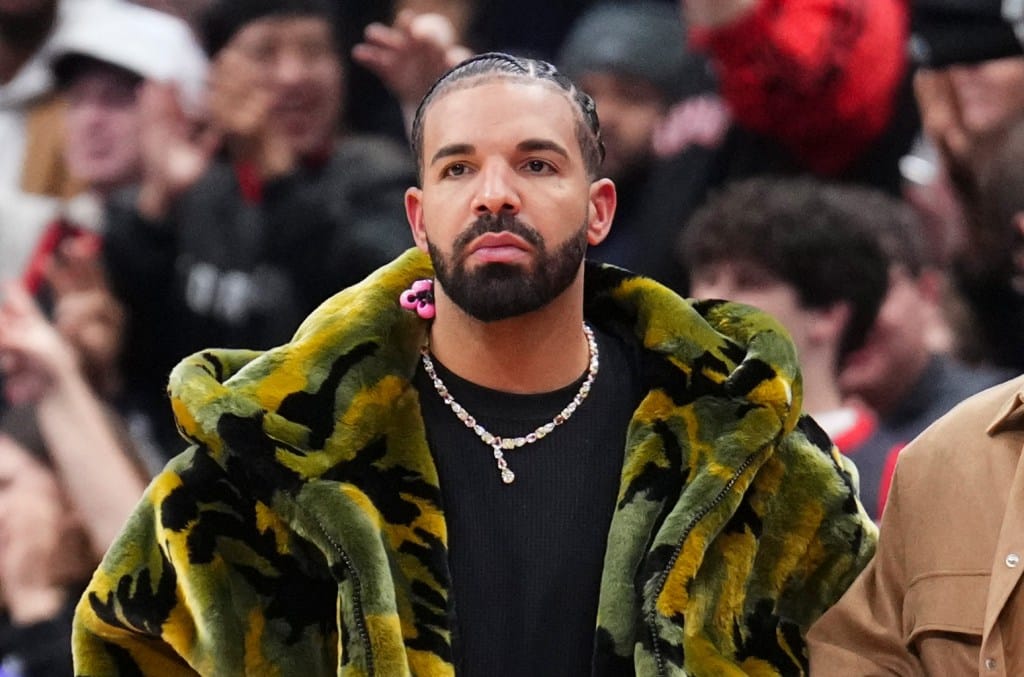

A federal judge says Drake can move forward with discovery in his defamation lawsuit against Universal Music Group (UMG) over Kendrick Lamar’s diss track “Not Like Us,” allowing his attorneys to begin demanding documents like Lamar’s record deal.

UMG had asked Judge Jeannette A. Vargas to halt the discovery process last month, arguing that Drake’s case was so flawed that it would likely be quickly dismissed — and that the star was unfairly demanding “highly commercially sensitive documents” in the meantime.

But at a hearing Wednesday (April 2) in Manhattan federal court, the judge denied that motion in a ruling from the bench. The judge had hinted in earlier rulings that she does not typically delay discovery before deciding if a case will be dismissed, barring extraordinary circumstances.

Trending on Billboard

In response to the ruling, Drake’s lead attorney Michael Gottlieb said: “Now it’s time to see what UMG was so desperately trying to hide.” An attorney for UMG declined to comment, and a spokesman for the company did not immediately return a request for comment.

Lamar released “Not Like Us” last May amid a high-profile beef with Drake that saw the two stars release a series of bruising diss tracks. The song, a knockout punch that blasted Drake as a “certified pedophile” over an infectious beat, eventually became a chart-topping hit in its own right and was the centerpiece of Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show.

In January, Drake took the unusual step of suing UMG over the song, claiming his label had defamed him by boosting the track’s popularity. The lawsuit, which doesn’t name Lamar himself as a defendant, alleges that UMG “waged a campaign” against its own artist to spread a “malicious narrative” about pedophilia that it knew to be false.

UMG filed a scathing motion seeking to dismiss the case last month, arguing not only that it was “meritless” but also ridiculing Drake for suing in the first place. Days later, the company asked Judge Vargas to pause discovery until she ruled on that motion, warning that exchanging evidence would be a waste of time if the case was then immediately tossed out of court.

But in a quick response, Drake’s lawyers argued discovery must go on because the lawsuit was not going anywhere: “UMG completely ignores the complaint’s allegations that millions of people, all over the world, did understand the defamatory material as a factual assertion that plaintiff is a pedophile.”

Following Wednesday’s decision, Drake’s attorneys will now continue to push ahead with seeking key documents and demanding to depose witnesses. That process will continue unless the judge grants UMG’s motion in the months ahead and dismisses the lawsuit.

In the earlier filings in the case, UMG attached the actual discovery requests filed by Drake’s team, detailing the materials his attorneys are seeking.

Among many others, they want documents relating to decisions on “whether to omit or censor any lyrics” from “Not Like Us” during the Super Bowl halftime show; anything related to the promotion of the song on Spotify and Apple Music; and any communications with the Recording Academy ahead of Lamar’s string of award wins at the Grammy Awards in February; and “all contracts and agreements between you and Kendrick Lamar Duckworth, his agents, or anyone working on his behalf.”

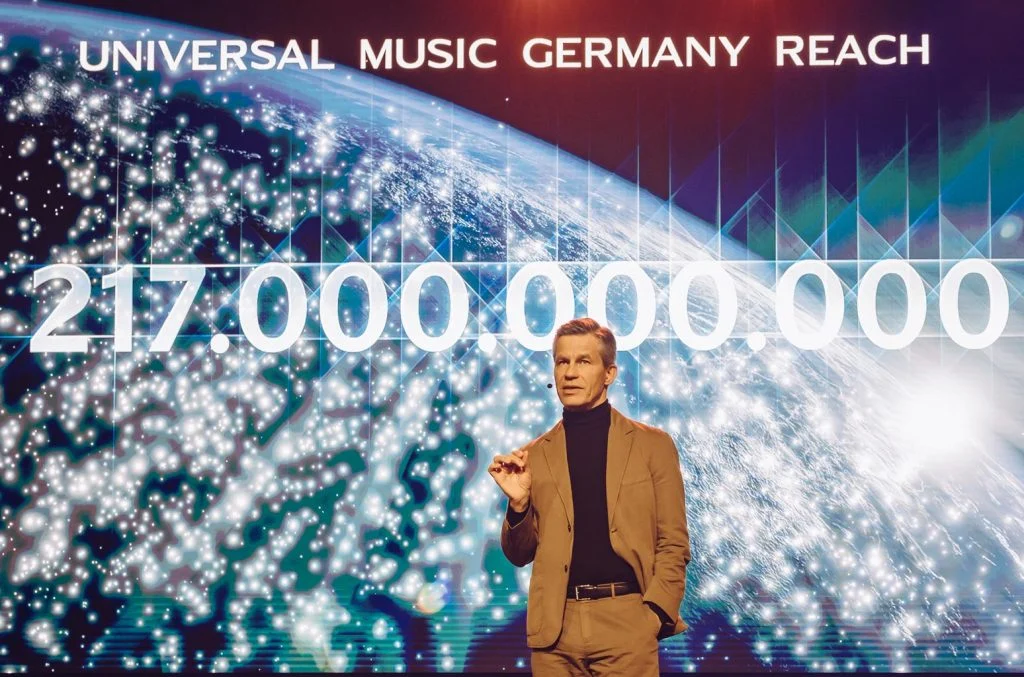

At Universal Inside, held Wednesday (March 26) at the Tempodrom in Berlin, UMG Central Europe chairman/CEO Frank Briegmann showcased some of the label’s acts, updated attendees on the state of the German music market and offered a glimpse into the company’s future.

After an appearance by the pop act Blumengarten, Briegmann shared some good news about the German business. As streaming growth slows in other regions, Germany still has plenty of headroom, which is why the market grew 7.8% in 2024, surpassing the 2 billion euro mark for the first time. He also made the point that this was good news for artists, who one study showed increased their collective revenue faster than labels between 2010 and 2022.

Briegmann also laid out a plan for growth that relies on UMG’s “artist-centric model” to increase payments to acts that meet certain criteria, as well as the “streaming 2.0” idea that is intended to induce superfans into paying more for subscriptions. The label had an impressive 2024, accounting for five of the year’s top 10 albums, including Taylor Swift and Billie Eilish releases in the top two spots. Briegmann also pointed to the success of UMG’s classical label Deutsche Grammophon, where he is also chairman/CEO, as a particular highlight.

Trending on Billboard

Much of the potential for growth lies in superfans, Briegmann said, and pointed to the history of UMG’s efforts to identify, track and reach them directly. The latest iteration of that is a new in-house direct-to-consumer operation, SPARKD, which will offer artists a new service to reach consumers with both albums and merchandise sold by UMG’s Bravado, which will be integrated into the label business in Germany. Bravado will continue to do business with both UMG artists and others. The idea is to use existing data to drive more different kinds of business — which would, in turn, generate more data. Already, Briegmann said, Bravado had grown its German merchandise revenue by 50% in the last three years, thanks in large part to its direct-to-consumer business.

Universal Inside is never all business, and as usual, Briegmann introduced some of the label’s artists. He briefly interviewed German pop star Sarah Connor, who spent much of her career singing in English but will soon release the final album of a German-language album trilogy, Freigeistin. Deutsche Grammophon president Clemens Trautmann introduced the label’s star pianist Vikingur Ólafsson, and Gigi Perez played two songs on acoustic guitar.

The event closed with a brief speech from Berlin Senator for Culture and Social Cohesion Joe Chialo about the significance of the Electrola label, after which the German act Roy Bianco & Die Abbrunzati Boys played a few songs, joined for the classic “Ti Amo” by the schlager icon Howard Carpendale.

BEAT Music Fund, the dance music investment company from Armada Music Group, acquired the rights to “a large portion” of masters from DJ, producer and Turbo Recordings founder Tiga. The deal includes Tiga’s “Sunglasses at Night,” “Bugatti,” “You Gonna Want Me,” “Let’s Go Dancing” and “HAL” featuring Kölsch. BEAT previously signed catalog deals with Kevin Saunderson, Markus Schulz, Robbie Rivera, Jax Jones, Amba Shepherd, VIVa MUSiC, Sola Records, King Street Sounds, Chocolate Puma and others.

Hook, the AI-powered platform that allows users to legally remix songs by top artists while earning income from those remixes, closed an additional $3 million in funding, bringing the startup’s total funding to $6 million. This round includes new investments from Khosla Ventures, Kygo‘s Palm Tree Crew, and The Raine Group. Continued support came from existing investors including Imaginary Ventures, Steve Cohen‘s Point72 Ventures, KSHMR and Edgar Bronfman, Jr.‘s Waverley Capital. The investment will help accelerate Hook’s marketing efforts and hiring, with a focus on user acquisition.

Trending on Billboard

Japanese record label Teichiku Entertainment signed a distribution partnership with Believe for Japan and the rest of the world. Through the deal, the companies aim to expand Teichiku’s digital footprint by leveraging Believe’s global DSP network, technology and digital-first expertise to bring Japanese enka, kayōkyoku and pop music to a wider audience globally.

Indian record label and music publisher Times Music acquired Indian regional record labels Symphony Recording Co. and ARC Musicq. These are Times Music’s first acquisitions since Primary Wave Music invested in the company to speed up its growth worldwide. Symphony, described in a press release as “the undisputed leader of Tamil spiritual and devotional music,” has a catalog of more than 350 audio and 100 video albums and boasts YouTube views of nearly 2 billion, with revenue on the platform doubling in the past four years, according to the release. ARC Musicq, which has been distributed by Times Music since 2017, is a label specializing in Indian folk music and film soundtracks within the Kannada music market. ARC also boasts more than 2 billion views on YouTube, with revenue quadrupling in the last three years, according to the release.

Independent U.S.-based K-pop label hello82 struck a partnership with One Hundred Label, the Korean entertainment company behind THE BOYZ. Under the deal, hello82 is serving as the exclusive physical distributor for the group’s album Unexpected, which was released on March 17. To support the release, hello82 is erecting immersive fan experiences at its brick and mortar fan spaces in Los Angeles and Atlanta, and at pop-up shops in major markets including New York, Chicago and San Diego throughout March. Hello82 previously signed similar deals with KQ Entertainment (ATEEZ, hikers) and FNC Entertainment (P1Harmony).

Ninja Tune struck a licensing partnership with Reactional Music, the music personalization platform allowing real-time interactive music integration in gaming, automotive and digital environments. With the deal, Ninja Tune’s labels and publishing division, Just Isn’t Music, have licensed the rights to tracks from its catalog for use in Reactional’s music personalization engine and music delivery platform. Ninja Tune’s labels include Brainfeeder, Counter Records, Technicolor, Big Dada and Foreign Family Collective, which have collectively released music by Thundercat, Bonobo, Little Dragon, Run the Jewels, ODESZA, Peggy Gou and others. Reactional’s platform is now live on Unity and Unreal Engine. It is being used by developers and creators in Europe, the United States, China and Southeast Asia.

ADA, the independent music distribution and artist services arm of Warner Music Group (WMG), acquired music tech startup RSDL.io, which provides automated accounting and a simplified view of multiple revenue streams for artists and labels. Founded by tech executives Mike Holmes, Jim Sella and Bill Sella and music industry players Alex Brahl (S7 Management) and songwriter-producer Shep Goodman, RSDL.io lets users facilitate payments and manage splits and recoupments and “allows for multi-level artist and contributor payout functionality and insights,” according to a press release.

EMPIRE struck a multi-year partnership with sound separation and lyric transcription technology company AudioShake under which the San Francisco-based label will use AudioShake’s stem and lyric separation technologies to create stems and lyrics for its catalog. EMPIRE will use AudioShake’s AI to produce stems for use in synch licensing, immersive formats and new music licensing models.

Musical AI, the AI rights management platform for music and audio, is partnering with Nashville-based artist-model platform and VST plugin First Rule to build fully-licensed AI agents and models designed to support music makers. Through the deal, Musical AI will provide licensed training data to First Rule, which will use the data to train musical agents and models aimed at assisting artists and producers. Musical AI will also provide attribution technology and payment processing “to ensure First Rule can prioritize rightsholder consent, credit, and compensation,” according to a press release. Using this data, First Rule will train its proprietary models to ensure they are able to produce high-quality results. This will allow artists and producers to train their own “Musical Essence or M.E Models on their distinctive style and approach,” then license those models to others to use in First Rule’s Co-Writer, a generative AI-powered VST plugin the company is currently building that will work in any digital audio workstation.

Sony Music Entertainment India and Tiger Baby — the Indian production company formed by filmmakers Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti — formed Tiger Baby Records, a joint-venture music label dedicated to fostering emerging talent. For one of its first projects, the new label has partnered with jewelry brand Tanishq for a wedding song composed by Abhishek-Ananya and performed by Poorvi Koutish. It also recently released the soundtrack for Superboys of Malegaon, a film based on the life of filmmaker Nasir Shaikh, that was composed by Sachin-Jigar and written by Javed Akhtar. Tiger Baby Records will additionally release original music curated by Ankur Tewari that will spotlight emerging artists and launch a “City Sessions” initiative with Mumbai’s Island City Studios in which singer-songwriters will be offered the opportunity to refine their craft, collaborate with established artists and more.

Universal Music Group (UMG) and HEAT — a new marketplace connecting animators, game developers and 3D artists with a trove of motion data and music — formed a collaborative initiative involving Lil Wayne and CG5 that will make licensed tracks from both artists available to game developers for the first time. Beginning May 1, Lil’ Wayne tracks “Uproar” and “GO DJ” and CG5 tracks “I See A Dreamer,” “Sleep Well,” “Let Me In” and “Dancin’” will be available through the HEAT platform, allowing game creators to integrate those tracks into their projects.

Secretly Distribution struck a global distribution deal with Invada Records, a U.K.-based independent label co-owned by musician, producer and composer Geoff Barrow (Portishead, BEAK >) and his longtime business partner Redg Weeks. Invada has released music by artists including DROKK, The KVB, Jeremy Gara (Arcade Fire), BEAK >, Divide And Dissolve, Anika, Billy Nomates, Gazelle Twin, Colin Stetson, Sleafords Mods, TVAM, Benefits and Julian Cope. It has additionally released scores for films, TV shows and video games including Stranger Things, Drive, Ex Machina, Solaris, Red Dead Redemption 2, Hannibal, Dark, Annihilation and Black Mirror.

Sweet Relief Musicians Fund and Sweetwater launched The Hearing Health Fund at Sweet Relief Musicians Fund, which will provide support for the growing number of music professionals who face hearing-related challenges, including hearing loss and tinnitus. According to research cited in a press release, seven in 10 music venue staff are exposed to noise levels above the daily recommended limit, while only 15% reported using hearing protection on a regular basis. Through the fund, professionals can receive a free, three-part hearing screening with a certified audiologist and free Etymotic Research ER-20XS High Fidelity Earplugs. Music pros can navigate here to apply for the Hearing Health Fund.

Music technology company Audoo partnered with German performing rights society GEMA on GEMA’s music impact study, which aimed to quantify the commercial value of background music in gastronomy and retail spaces. The study used Audoo’s audio meters — or music recognition hardware — that the company had installed in hundreds of venues. Overall, it found that the use of background music increased retail sales by an average of 8% and gastronomic sales by an average of 5.4%. More information on the research can be found here.

Rhino Staging, which provides stagecraft and rigging crews across the U.S., acquired ROC Rigging, a provider of special event rigging services for entertainment, corporate and private events in the Palm Springs, Calif., area. Matt Talley, the founder/CEO of ROC Rigging, along with the company’s management team, will remain in place as the company integrates with Rhino.

UnitedMasters partnered with The Coca-Cola Company for an event to be held this month in São Paulo celebrating Brazil’s independent music scene. The two companies have also selected independent artist Alee to perform at Coke Studio at Lollapalooza Brasil, in addition to Zudizilla, who will perform on the main stage.

Drake’s lawyers are quickly firing back after Universal Music Group’s recent attacks on the rapper’s defamation lawsuit over Kendrick Lamar’s diss track “Not Like Us,” arguing that “millions of people” around the world think the song was literally claiming Drake is a pedophile.

In a motion filed in federal court Thursday (March 20), Drake’s team hit back at UMG’s core defense against the star’s libel lawsuit: That scathing lyrics are par for the course in diss tracks and that most listeners wouldn’t take such “outrageous insults” as statements of fact.

That argument is “doomed to fail,” Drake’s lawyers say in the new filing, because many people really did come away from Lamar’s song believing that he was — as a matter of fact — calling Drake a pedophile.

Trending on Billboard

“UMG completely ignores the complaint’s allegations that millions of people, all over the world, did understand the defamatory material as a factual assertion that plaintiff is a pedophile,” Drake’s attorneys write. “UMG also ignores [the lawsuit’s claim] that the statements in question (and surrounding context) implied that the allegations were based on undisclosed evidence and the audience understood as much.”

Thursday’s filing came in response to a motion from UMG, filed earlier this week, that seeks to halt all discovery in the case. In it, the music giant argued that Drake’s case was almost certain to be dismissed, meaning that handing over evidence would be a waste of time — particularly since his lawyers are allegedly demanding a vast swath of sensitive materials, including Lamar’s record deal.

But in the new response, Drake’s lawyers say that motion “does not come close” to showing that the discovery in the case is the kind of “undue burden” that must be halted: “UMG has not stated how long it expects discovery to take, the costs associated with discovery, or any other indicator that might demonstrate why discovery will be overly burdensome.”

Lamar released “Not Like Us” last May amid a high-profile beef with Drake that saw the two stars release a series of bruising diss tracks. The song, a knockout punch that blasted Drake as a “certified pedophile” over an infectious beat, eventually became a chart-topping hit in its own right and was the centerpiece of Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show.

In January, Drake took the unusual step of suing UMG over the song, claiming his label had defamed him by boosting the track’s popularity. The lawsuit, which doesn’t name Lamar himself as a defendant, alleges that UMG “waged a campaign” against its own artist to spread a “malicious narrative” about pedophilia that it knew to be false.

This week has seen UMG mount its first formal counterattack — first by filing a motion to dismiss the case on Monday (March 17), then seeking the halt discovery on Tuesday (March 18). In the strongly-worded request to toss the case out, UMG argued not only that the lawsuit was “meritless,” but that the star filed it simply because he was embarrassed: “Instead of accepting the loss like the unbothered rap artist he often claims to be, he has sued his own record label in a misguided attempt to salve his wounds.”

Drake’s attorneys have said in public statements that the label’s motion to dismiss the case is a “desperate ploy by UMG to avoid accountability” and that it will be denied. They will file a formal response in opposition to that motion in the weeks ahead.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio