magazine

Page: 4

Hey man, what’s happening?” LaRussell says exuberantly as he walks down the street on a bright Wednesday morning in the Bay Area.

The passerby who just shouted hello will be the first of several to call out greetings to the 30-year-old rapper as he ambles through his hometown of Vallejo, Calif. “Hey!” “What’s up, brother?” “Hi!” he calls back to them like a particularly neighborly sort of mayor — if mayors wore fuzzy hats embroidered with the face of Winnie the Pooh.

“I walk each morning, and no matter if I’m on this side of Vallejo or the north side where my mom lives or wherever, people are excited to see me,” he says, “because I mean something to this place. I’m someone who really made it who went to the same schools.”

LaRussell isn’t just a local, but a local celebrity — one who has created an innovative, community-focused infrastructure to nurture and forge his artistic independence. He has endeared himself to fans with not only his breezy, conversational flow — delivered over groovy production on an astounding 40 albums going back to 2018 — but also a business model built around sliding scales that allow them to bid on everything from merchandise to concert tickets to royalties to the chance to hang with him and play pickleball.

Trending on Billboard

“In the beginning, I had zero dollars, so I didn’t really need checks and balances. If you gave me a dollar, I was richer than I was prior to that,” he says. “As that elevated, I started finding ways to make it make more sense.”

LaRussell’s success is centered on him being both immensely charming, with a wide and frequent smile that’s certifiably megawatt, and prolific. He says it’s never taken him more than 15 minutes to write a song, and songs come to him frequently, creating a lot of material to monetize. “The universe really gives it to me,” he says. As an independent artist, he has the freedom to determine his own release schedule, which so far in 2025 has included dropping five albums.

“The way labels treat artists where they can only release so much music at a certain time, it’s like you’re telling someone to stop doing what they love and not feed their family,” he says. “Music just kind of oozes out of me. It’s what I do when I’m sad, happy, stressed, so being independent allows me to really cater to how I feel as a human.”

LaRussell

Jessica Chou

LaRussell releases music through Good Compenny, his label and company that’s based in the creative compound he has built in Vallejo. The sprawling space offers rooms and tools for recording, content creation, photography, merch shipping and more, with construction currently underway on a storefront that will sell all things LaRussell, including his first book, Limitless: The 10,000 Shot Theory, a hybrid memoir/self-help tome he calls “a book about life” that has sold thousands of copies since he self-published it in 2023. Upstairs from the work facilities, an eight-unit residential complex houses him and his family, along with a crew of engineers, videographers, managers and protégés like fellow rapper Malachi.

Here the vibe is familial and the ability to create is always just a few doors down the hall. LaRussell equates this hub to building “a store in a place that didn’t have a store. I didn’t know what people liked, but I knew what I loved and what I needed.”

While he considered decamping to New York or Los Angeles earlier in his career, “because you think all the infrastructure is there, so you have to move there to succeed,” he was broke, so moving wasn’t an option. “That encouraged me to build my platforms and my independence here,” he says of Vallejo, a city of roughly 122,000 north of Berkeley. And “here” happens to be a place where he’s now part of an esteemed hip-hop lineage: Vallejo’s native sons also include E-40 and Mac Dre.

Now he’s literally making change in his own backyard through a series of performances he and his team host at the compound, where music, food, drinks and bounce houses for kids are all part of the package for a suggested donation of $100 (though the team has accepted much less; those who can’t afford to pay more are subsidized by those who can).

LaRussell says he doesn’t tour in the traditional sense, although he does perform more intermittent dates “all throughout the year” at venues nationwide ranging in size from 200 to 2,000 capacity. He says intimate spaces “are preferred” — like the NPR Tiny Desk concert he did with a crew of 10 musicians and singers last November that has aggregated hundreds of thousands of views.

LaRussell photographed May 13, 2025 in Vallejo, Calif.

Jessica Chou

For live shows, he accepts almost any ticket offer. “I like everybody to be in the building,” he says, noting that most people do pay more than the minimum, with several tiers of preset ticket prices also listed for most of his shows in traditional venues. The system is roughly the same with merch: His team screens all bids and sends counteroffers if the initial sum is too low. In 2024, Kickstarter recruited him for the Let Me Hold a Dolla campaign, which encouraged people to donate a buck to him en masse. While he initially thought he would decline the offer “because I really go out and work; I don’t like asking for handouts,” he ultimately decided it was OK to ask for “the bare minimum of support.” The campaign ultimately raised $39,423 from 713 backers, with those who donated getting rewards like early access to music, entry to a backyard show and a chance to spend a day with LaRussell.

Collaborators can even bid on LaRussell features, and he has been known to record 10 or 20 in a day. “The minimum I’m getting for a feature is like $500,” he says, “so if I do 20 at just the minimum offer, I’m making 10 grand that day.” Selling portions of his song royalties to fans also generates income: His catalog has 100.2 million on-demand official global streams, according to Luminate.

His proverbial open-door policy to all aspects of his career naturally also leaves him open to the interesting opportunities that come walking in. When one backyard show attendee later became the head of marketing for the San Francisco Giants, she recruited LaRussell to record an anthem for the team to be played at its home, Oracle Park. He wrote the song, “Nothin Like It,” immediately after getting off a Zoom call discussing the project, then “sent it back to the marketing team in like five minutes.” He’s currently working on more music, another book and a comedy in the style of Chappelle’s Show.

But even as his projects expand beyond Vallejo, he knows his wider success is rooted here: Staying part of this community means that as he champions the city, it champions him right back.

“You don’t just see me online rapping,” he says, continuing his stroll through town. “You see me with the kids and in the public. You see me as a human before you see me as a rapper. I think that feeds a different type of support between me and my base.”

This story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

When Tito Double P was deciding on a name for his debut album, he remembered a comment about him that had gone viral on social media.

“Tito se ve incómodo,” someone wrote, pointing out that Tito looked “uncomfortable” in a photo where he appeared in the background with other artists, including his superstar cousin, Peso Pluma.

“As a songwriter, a lot of artists would invite me to hang, and eventually, they would ask me for a song during those hangouts,” the 27-year-old musician explains with a smirk on his face. “But I was always in the background, looking very serious in photos and videos, and someone left that comment — I don’t remember if it was on TikTok or Instagram — and it got a bunch of likes. And from then on, whenever I uploaded a photo on social media, even if I looked happy, everyone would comment, ‘Se ve incómodo.’ It became a thing and I thought, ‘That’s what we should name the album — it will give people something to talk about.’ ”

Today, Tito Double P seems anything but incómodo. Last summer, his set of the same name shot to No. 1 on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart, dethroning Peso’s Éxodo, and earlier this year, Tito embarked on an arena and amphitheater tour — his first trek in the United States — for which his training included doing vocal and breathing exercises with a voice coach over the phone. With his No. 1 album and sold-out tour, Tito, who only just launched his career as an artist last year, has gone from songwriter to superstar-in-the-making.

Trending on Billboard

“There’s no manual for that, and it’s not an easy process to go from songwriter to singer,” the Sinaloa, Mexico-born artist reflects. “At first, it was always ‘Peso Pluma’s cousin’ or ‘That guy writes for Peso.’ Eventually, I finally became Tito Double P.”

Tito (born Roberto Laija) penned some of Peso’s early hits, including “El Belicon,” “Siempre Pendientes,” “PRC” and “AMG,” all of which catapulted onto the Hot Latin Songs chart in 2022 and helped usher in a global era for corridos and regional Mexican music in general. They also helped Tito become the genre’s most in-demand songwriter, which in turn laid the groundwork for his evolving career. He could have kept to songwriting, but Tito wondered what would happen if he released his own music on indie label Double P Records, which Peso and his manager/business partner, George Prajin, co-founded.

“First I said, ‘Let me release one song,’ because I kind of thought nothing would happen. But then it became a hit, so I released another one and then another,” he says. “The team asked me if I was going to be a singer or a songwriter and I said, ‘Let me record an album and see what happens.’ I also remember thinking that I wouldn’t tour, I’d just release music. But after performing onstage, now I don’t want to get off. I never thought this would happen to me.

“I went from songwriter to singer to artist in less than a year,” he explains, still sounding somewhat awed by his rapid ascent.

With his charming boy-next door personality, hoarse vocals, in-your-face delivery and unique writing style — which he compares to writing rap songs because he adds “too many words” and records in double-time — Tito stands out among música mexicana’s ever-growing field of emerging artists. He scored his debut Billboard chart entry as an artist with “Dembow Bélico,” a collaboration with Joel De La P and Luis R. Conriquez that hit No. 35 on Hot Latin Songs in July 2023. His first top 10 arrived a little less than a year later with the Joel De La P and Peso collaboration “La People II.” Overall, Tito has seven career entries on the all-genre Billboard Hot 100 and 23 career entries on Hot Latin Songs; Incómodo — which ruled Top Latin Albums for nine nonconsecutive weeks — reached No. 11 on the Billboard 200 last October. Tito closed 2024 at No. 15 on the year-end Top Latin Artists list, with 1.7 billion on-demand official streams in the United States, according to Luminate.

Tito says Peso is proud of his accomplishments — even if they’ve dethroned him on the charts. “He was proud and like, ‘¿Qué onda?’ [What’s going on?], at the same time,” he recalls with a gentle, almost timid smile as he remembers Peso’s reaction to Incómodo hitting No. 1 on Top Latin Albums. “It’s never a competition between us. To be honest, he was like, ‘Better you than anyone else to take me out.’ ”

That reflects the ethos at Double P Records, whose roster also includes Deorro, Dareyes de la Sierra and Jasiel Nuñez.

“The artists on the label get together in the studio to show each other what we’re working on and get feedback like, ‘That idea is great,’ or ‘I like the lyrics but not the tune.’ We share everything, from the producers we’re working with to writing together and collaborating. We’re like a family,” Tito says. “And we also get to be our own bosses. There’s no set timeline of when I have to release a song. We have so much freedom.”

Tito is gearing up for future projects to maintain his momentum, including “tons of new music” with which he plans to shift from corridos singer to writing and recording songs about desamor (heartbreak). He also has an upcoming joint EP with Peso: “We have a lot of songs, but we’re still working on it because I was on tour and he had his own projects — but something big is coming with [Peso],” he teases of the project, which has no set release date.

Tito’s life has changed so much over the last year — but there’s still one moment in particular that reminds him of his growth. “One time, when Peso was just starting, he asked me to go do an interview with him because he didn’t want to go alone,” he recalls. “Literally no one knew who I was at the time, and I just sat there next to him, didn’t say a word, until the interviewer asked me, ‘And who are you?’ And I quickly responded, ‘Oh, no, I’m just his cousin.’ Today, I’m much more loose, more comfortable. Like, it’s still me but just more mature, motivated and grateful for everything that has happened and for what is coming.”

This story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

True to her name, Mariah the Scientist’s songs are often the result of several months, and sometimes years, spent combining different elements of choruses and verses until finding the right mixture. But when it came time for the 27-year-old to unveil her latest single, the sultry “Burning Blue,” the R&B singer-songwriter was at a crossroads. So, she experimented with her promotional strategy, too — and achieved the desired momentum.

“Mariah felt she was in a space between treating [music] like a hobby and this being her career,” recalls Morgan Buckles, the artist’s sister and manager. And so, they crafted a curated, monthlong rollout — filled with snippets, TikTok posts encouraging fan interaction and various live performances — that helped the song go viral even before its early May arrival. Upon its release, Mariah the Scientist scored her first solo Billboard Hot 100 entry and breakthrough hit.

Trending on Billboard

Mariah Amani Buckles grew up in Atlanta, singing from an early age. She attended St. John’s University in New York and studied biology, but ultimately dropped out to pursue music. Her self-released debut EP, To Die For, arrived in 2018, after which she signed to RCA Records and Tory Lanez’s One Umbrella label. She stayed in those deals until 2022 — releasing albums Master and Ry Ry World in 2019 and 2021, respectively — before leaving to continue as an independent artist.

“Over time, you start realizing [people] want you to change things,” Mariah says of her start in the industry. “Everybody wants to control your art. I don’t want to argue with you about what I want, because if we don’t want the same things, I’ll just go find somebody who does.”

Mariah the Scientist

Carl Chisolm

In 2023, after six months as an independent artist, Mariah signed a joint venture deal with Epic Records and released her third album, To Be Eaten Alive, which became her first to reach the Billboard 200. She then made two Hot 100 appearances as a featured artist in early 2024, on “IDGAF” with Tee Grizzley and Chris Brown and “Dark Days” with 21 Savage.

“Burning Blue” marks Mariah’s first release of 2025 — and first new music since boyfriend Young Thug’s release from jail following his bombshell YSL RICO trial. The song takes inspiration from Purple Rain-era Prince balladry with booming drums and warbling bass — and Mariah admits that the Jetski Purp-produced beat on YouTube (originally titled “Blue Flame”) likely influenced some lyrics, too. She initially recorded part of the track over an unofficial MP3 rip, but after Purp caught wind of it and learned his girlfriend was a fan, he gave Mariah the beat. Mariah then looped in Nineteen85 (Drake, Nicki Minaj, Khalid) to flesh out the production.

“I [recorded the first part of ‘Burning Blue’] in the first room I recorded in when I first started making music in Atlanta,” Mariah says. “I don’t want to say it was a throwaway, but it was casual. I wrote some of it, and then I put it to the side.”

Once Epic A&R executive Jennifer Raymond heard the in-progress track, she insisted on its completion enough that Mariah and her collaborators convened in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, in February to finish the song. By that point, they sensed something special. Mariah shared a low-quality snippet on Instagram, but Morgan — who joined as a tour manager in 2022 — knew a more polished presentation was needed to reach its full potential.

Morgan Buckles (left) and Mariah the Scientist photographed May 20, 2025 in New York.

Carl Chisolm

Morgan eyed Billboard’s Women in Music event in late March as the launchpad for the “Burning Blue” campaign. Though Mariah wasn’t performing or presenting at the event, Morgan wanted to take advantage of her already being in glam to shoot a flashier teaser than Mariah’s initial IG story, which didn’t even show her face.

The two decided on a behind-the-scenes, pre-red carpet clip soundtracked by a studio-quality snippet of “Burning Blue.” Posted on April 1, that clip showcased its downtempo chorus and Mariah’s silky vocal and has since amassed more than two million views, with designer Jean Paul Gaultier’s official TikTok account sharing the video to its feed. Ten days later, Morgan advised Mariah to share another TikTok, this time with an explicit call to action encouraging fans to use the song in their own posts and teasing that she “might have a surprise” for fans with enough interaction.

Mariah then debuted the song live on April 19 during a set at Howard University — a smart exclusive for her core audience — as anticipation for the song continued to build. Two weeks later, “Burning Blue” hit digital service providers on May 2, further fueled by a Claire Bishara-helmed video on May 8 that has over 7 million YouTube views.

“We’re at the point where opportunity meets preparation,” Morgan reflects of the concerted but not overbearing promotional approach. “[To Be Eaten Alive] happened so fast, I didn’t even know what ‘working’ a project meant. This time, I studied other artists’ rollouts to figure out how to make this campaign personal to her.”

“Burning Blue” debuted at No. 25 on the Billboard Hot 100 dated May 17, marking Mariah’s first time in the top 40. Following its TikTok-fueled debut, the song has shown legs at radio too, entering Rhythmic Airplay, R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay and Mainstream R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay — to which Morgan credits Epic’s radio team, spearheaded by Traci Adams and Dontay Thompson. “[The song] ended up going to radio a week earlier [than scheduled] because Dontay was like, ‘If y’all like this song so much, then play it!,’ and they did,” Morgan jokes.

With “Burning Blue” proving to be a robust start to an exciting new chapter, Mariah has a bona fide hit to start the summer as she prepares to unleash her new project, due before the fall. She recently performed the track on Jimmy Kimmel Live! and will have the opportunity to fan the song’s flames in front of festival audiences including Governors Ball in June and Lollapalooza in August. But as her following continues to heat up, Mariah’s mindset is as cool as ever.

“I’ll take what I can get,” Mariah says. “As long as I can use my platform to help people feel included or understood, I’m good.”

Mariah the Scientist

Carl Chisolm

A version of this story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

Rainy Monday mornings are rarely settings for celebration. But on this one, The Orchard CEO Brad Navin has 48,000 reasons to smile: The vinyl edition of Bad Bunny’s DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS has finally shipped, returning the album to No. 1 on the Billboard 200 with the largest vinyl sales week since Luminate began tracking data in 1991.

It’s the Puerto Rican star’s fourth straight Billboard 200 chart-topper, all of which have been released through his label, Rimas, in partnership with The Orchard, the services company that launched as a digital distributor in 1997. After an initial investment in 2012, Sony bought The Orchard outright in 2015, and since — through smart mergers and competitive acquisitions of companies like IODA, RED and AWAL, as well as a global outlook and a top-tier services offering — it has become the U.S. market leader among all distribution companies, boasting an 8.9% current market share for 2025 through May 15, according to Luminate, nearly triple its next-closest competitor.

For the past 15 years, Navin — who joined the company initially in 2003, rising to interim CEO in 2010 before taking over the post full time shortly after — has steered that ship, navigating it through the streaming revolution, the globalization of the business and, more recently, the democratization of music that has led to distribution becoming the industry’s hottest sector, with dozens of new startups and millions in private equity funding flooding the space.

Trending on Billboard

Still, as Navin notes, “No one has invested in the independent sector more than The Orchard has in the last 15-plus years. We have helped our clients sign artists, grow their business, grow rights within their business, expand where their business might be located — there is not a client in The Orchard that has not grown dramatically while they’ve been with us.”

From the start, The Orchard did things differently. Co-founders Richard Gottehrer and Scott Cohen started the company years before the iTunes Store revolutionized digital downloads and quickly took a global approach. “For years, it was difficult for independent artists to get noticed and get distribution, and early on, we realized it almost didn’t matter where you were from or what language you were speaking — music was music,” Gottehrer says. “It’s a universal language and sharing that was important.”

The past decade has proved that to be prescient: In April, the RIAA reported that Latin music revenue in the United States surpassed $1 billion for the third straight year, and The Orchard is on the front lines of that through partnerships with Rimas (which itself recently bought a stake in Dale Play), Double P Records and the recent acquisition of Altafonte. The company, which maintains 50 offices on six continents, “gives you the tools to think big and not be restricted in your deal or resources,” says George Prajin, who co-founded Double P Records with Peso Pluma.

“[They] prioritize making sure that their partners can reach everyone worldwide,” says Tunde Balogun, co-founder and CEO of LVRN, which signed a distribution deal with The Orchard after exiting its joint venture with Interscope Records. “Whether it’s a genre or a region, it’s amazing to experience how they partner with entrepreneurs and artists and back them and help them grow.”

And as part of Sony, The Orchard has only strengthened its position. “A lot of the new companies springing up in the space are owned by investment vehicles or backed by finance money, and it’s not really clear what their long-term proposal is,” The Orchard president/COO Colleen Theis says. “We serve the independent community, and that’s always going to be our client base and our focus.”

With this proposition, The Orchard continues to attract new clients, from traditional partnerships to its 2022 investment in Rimas to taking stakes in Fat Possum and Mass Appeal. “Sometimes modern automation tricks us into believing these service providers are all the same, but when done right, it’s a far more complex operation than most people realize,” says Tyler Blatchley, co-founder of Black 17 Media, in which The Orchard has taken a minority stake.

“The deals we’ve done over the years have always been very strategic: a specific genre, a specific region of the world, a specific synergy or enhancing the value proposition that’s going to benefit our clients and our reach,” Navin says. “Is there a great operator or a great entrepreneur there that we want to be a part of what we’re doing? That’s where my motivation lies and that’s how we’ve done our deals historically: working with great operators.”

Brad Navin with Mass Appeal CEO Peter Bittenbender (left) and co-founder Nas.

Courtesy of The Orchard

You’ve been at The Orchard for more than 20 years. What was it like when you first got here?

We were a digital distributor before there was digital. It was pre-iTunes, let alone iPhone. I give the founders, Richard Gottehrer and Scott Cohen, a lot of credit — they had this understanding that the world was going to go online in some capacity. At the time, we were flipping over CDs and typing in label copy. That’s what digital meant for us back then.

It had to get more sophisticated to keep up with the volume and what was going to happen next. We wanted to control our own destiny, so we built around technology. And that became our great advantage because it taught us how to build a platform of services and the ability to integrate what’s next, without us needing to know what was next, necessarily. And that ethos exists today.

What did you feel The Orchard needed when you took over as CEO in 2010?

The team before me had the vision to go out all over the world — that music from everywhere matters. And now we live in a time where music from anywhere can stream everywhere. But we hadn’t yet built out our own technology. We were wildly unprofitable, we were in a terrible reverse merger from back in 2007-08, [and we were in a] total state of flux in management and what we were doing. And I came and said, “We need to build this out; here’s how I think it will transform the company.”

Sony invested in 2012 and then bought The Orchard in 2015. How did that work?

In the early days, there was some trepidation about being acquired by a major: Do they understand the independent sector? Do they understand all things digital and what’s going on? But as Richard said on the heels of the transaction, “We were bought by a f–king music company. Not by a bank, not by some people looking to liquidate.”

We had a company with the size that they are on a global level that was going to make sure that IP [intellectual property] was protected, that the value of music and how it’s going to be represented in a streaming world, or a short-form video world, would be represented in the right way, and that, ultimately, The Orchard and our clients were going to benefit. And that’s going to include whatever’s next, like [artificial intelligence]. As long as the creators are in the monetary chain and protected, I don’t know if I care what it is, necessarily.

Even in 2015, 50% of your business was outside the United States. How has that early global focus paid off?

To go into markets all over the world, where there are massively important catalogs and repertoire of varying genres, was an opportunity. As the [digital service providers] began to expand their reach and launch in those markets, we were sitting right there with all this music already available. You’ve got to be part of the local music scene and culture for the value proposition of artists and labels and the local music services. But we also need to be able to move music regionally and globally as it starts to happen. And that’s the way we function.

You said distribution used to be the unsexy part of the business. Now everyone wants to be in distribution. What changed?

The independent sector has always been about partnership, pushing the envelope on marketing, or the next format, or new ways to promote. Basically, they’ve always been willing to f–k with stuff while the big IP companies want to hold back. And as artists become empowered, they start to question: “What’s the definition of a label? What do I need going forward?” That’s a big reason why the industry’s been shifting. The definition of a label, or an artist services company, or a distribution company — it’s all in flux.

What are you focused on now?

If I think about North America, in this last year, Kelsea Ballerini on Black River Entertainment is an example of how the independent sector supports artist development. You could say the same thing in a completely different form for G*59 and $uicideboy$ and their roster. Music that I think the industry wasn’t really aware of but their fans were aware of, that’s the power of the artist being able to be out there, building audiences and driving it forward — it’s stunning. Black 17 and the whole phonk thing that’s been going on — when you work with great entrepreneurs all over the world, there’s new categories of music that we didn’t go out and look for that are happening. This is what’s going on in our sector of the business that’s so exciting.

How many different levels of service do you offer?

It’s not just the different levels. If they want us to f–k off and just put their music out, we can do that. If they want us to hold hands and really be in bed working up to that street date, we’ll do that. There’s no one size fits all at all. There can’t be.

Does that affect the deals you do, to keep them flexible?

To some degree, but not to a wide degree. The influx of outside capital into the music industry the last 10 years, and large competitors being born out of other majors or large, stand-alone distribution companies, whatever you want to call it — competition is great. We thrive off of it. Imitation is the best form of flattery. What is concerning, though, is … there’s a lot of irresponsible deals that have entered the marketplace: low margin, high capitalization. The artists deserve to be in control. They deserve to get paid.

This story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

When Faye Webster is back home in Atlanta, she likes to visit Oakland Cemetery. “I always go there when I’m home from a tour and just walk around by myself,” she says.

It’s not that the cemetery is the final resting place of any of her loved ones, or that Webster enjoys checking out the tombstones of Atlanta’s rich and famous, like musician Kenny Rogers or golfer Bobby Jones, who are both buried there. She just sees it as “a peaceful, safe space” to find silence amid her increasingly chaotic life.

Last year, Webster, 27, released her fifth album, Underdressed at the Symphony, and played 77 shows to support it — a lot by anyone’s measure, but a touring itinerary that was particularly challenging for Webster. Despite her fast-growing success, the soft-spoken homebody has never loved the spotlight. “Navigating it is tough, but I had a friend give me the advice to call someone I love after the show every day to remind myself of what’s real,” she says. “So I asked my mom, ‘Hey, can I call you at 10:10 every night?’ Now we always do it.”

Trending on Billboard

She has other ways of making the road feel like home — like the added comfort of having her older brother Jack as her guitar tech; her best friend, Noor Kahn, on bass; and her bandmates of many years by her side. (Her other elder brother, Luke, handles her merchandise and graphic design.) She also has a go-to warmup routine for shows. “I always get everyone together and we recite the battle of the bands prayer from School of Rock: ‘Let’s rock, let’s rock today!’ Then we go onstage,” she says.

Originally, Webster had asked to meet at the cemetery for this interview, but with heavy rain projected in the forecast, we decide to talk over matcha and baked goods at a nearby café instead. Between bites of a guava pastry, Webster says that when she gets the rare opportunity to be at home, she spends time with friends and family or tends to her many hobbies, which include — but are not limited to — yo-yo, tennis, Pokémon, the Atlanta Braves and Animal Crossing. And, she says with a laugh, “I have so many collections of so many different things. So many dumb things.” Her house is littered with it all. “I was collecting alarm clocks for a while, then I filled a full shelf and I was like, ‘OK, there’s no more space.’ I did my yo-yo shelf, too. I have tons of vinyl. Now I need something new to collect, so I’m buying CDs,” she explains. Her latest purchase? A copy of Alison Krauss and Robert Plant’s Raising Sand from Criminal Records in Atlanta.

“I remember the first time I heard her sing when I was a kid. I thought, ‘I didn’t know people could sing like this,’ ” Webster recalls of Krauss. “She has this very soft, angelic, pristine voice. When I first heard her sing I thought, ‘I want to be her.’ ”

Faye Webster

Christian Cody

Webster self-released her debut, Run and Tell, an earnest and straightforward Americana record, in 2013 when she was just 16. Back then, her voice was still developing and didn’t yet have the bell-like clarity and melancholic whine that she is beloved for now. Soon after, Webster’s path crossed with the Atlanta hip-hop scene when she started photographing and hanging out with the young rappers signed to tastemaking indie label Awful Records. Around this time, she also grew closer to another emerging local rapper, Lil Yachty — whom she ultimately collaborated with on Underdressed single “Lego Ring.” With Awful, “It started as just a friendship for months, and then it grew to me signing there,” says Webster, who was an oddball addition to the label as its first non-rap artist.

But for Webster, it didn’t feel strange at all — she was just putting out music with help from her friends. “I loved my experience with Awful. I think, to this day, what I learned there was about creating this sense of family and community. I still hold those values today,” she says.

After releasing 2017’s Faye Webster with Awful, she moved to indie powerhouse Secretly Group and its Secretly Canadian label. There, she steadily accumulated millions of fans as she released 2019’s Atlanta Millionaires Club, 2022’s I Know I’m Funny haha and Underdressed. (Secretly also now distributes her self-titled album.)

Her career hit hyper-speed about two years ago when she scored surprise TikTok hits with “I Know You” and “Kingston” — which were about 7 and 5 years old, respectively, when they took off. Those viral moments shifted her audience away from indie-loving Pitchfork dudes and toward a younger, more female crowd; her recent shows have been marked by throngs of adoring fangirls. Ironically, Webster isn’t even on TikTok — and she barely posts on social media in general.

“Faye is amazing — and somewhat of a contradiction as an artist,” says Secretly Group vp of A&R Jon Coombs, who, with his team, signed Webster to Secretly. “She bucks industry trends by not being online that much, but she still has great social media success. She’s someone who is so impossibly cool, yet she likes traditionally uncool things like yo-yoing and gaming. All of these things combined make her a really compelling and singular artist.”

To connect her whimsical hobbies to her much more serious music career, Webster introduced custom yo-yos as merch in collaboration with Brain Dead Studios, which is run by her friend and creative director Kyle Ng. (“Individuality and being her own character adds so much to her as a musician,” he says.) She also incorporated Bob Baker Marionettes into the Ng-directed “But Not Kiss” music video; founded an annual yo-yo invitational in Berkeley, Calif.; started an active Discord server with a dedicated channel to all things Minions; and has repeatedly covered the Animal Crossing theme at her gigs.

“I look out at shows now and see people dressed up like Minions and having fun and singing and I think, ‘This is so beautiful. This is why I do it,’ ” Webster says. “I really appreciate that my music can resonate with anybody. That’s all I’ve ever wanted — for somebody to feel they can relate to my work.”

Faye Webster

Christian Cody

Her hobbies also seep into her songs, like Underdressed’s “eBay Purchase History” or Funny’s “A Dream With a Baseball Player,” which is about her lasting crush on Atlanta Braves star Ronald Acuña Jr.

“She has this ability to pack a short story into a single line,” Coombs says of her lyricism. From “The day that I met you I started dreaming” (“Kingston”) to “You make me want to cry in a good way” (“In a Good Way”) and “Are you doing the same things? I doubt it” (“Underdressed at the Symphony”), Webster’s economical songwriting often repeats phrases on a loop, each refrain cutting to a deeper emotional core. Her expertly crafted productions — Wurlitzer keys, smooth Southern-rock guitar and plenty of pedal steel — seal the deal.

For Webster, “initial reactions” and “gut feelings” are the anchors of the songwriting and recording process. “To me, I’m just like, ‘Oh, that sounded good! Let me say it again…’ However the song plays out is sometimes just the way it’s supposed to happen,” she says.

As part of that instinctive approach, Webster has historically recorded songs soon after writing them. “I just like to do things in the moment,” she says. “When writing a song, I’ve often texted my friends, my band, and tried to get everyone together while it’s still fresh.” She typically self-records her vocals at home and the rest in nearby Athens. Most recently, however, she tried recording Underdressed at famed West Texas studio Sonic Ranch.

“That was our first experience going somewhere new,” she says. “My producer [Drew Vandenberg] was like, ‘What if we go somewhere else?’ And I was like, ‘OK, if it’s you and it’s me and it’s Pistol [pedal steel player Matt Stoessel] and all the band, it shouldn’t matter where we go.’ ”

Now, as she works on her next album, Webster is taking another leap of faith: signing her first major-label deal with Columbia Records, where she’ll join a roster that includes Beyoncé, Vampire Weekend and Tyler, The Creator (whose Camp Flog Gnaw festival she performed at last year). When asked why she signed there, she pauses, taking a sip of matcha as she thinks. “It comes back to that initial gut, that initial intuition,” she finally answers. “[Columbia] feels like where I belong right now and that’s where I’m supposed to exist.”

Faye Webster

Christian Cody

Perhaps it’s thanks to the flexibility her time on indie labels offered, or the support system it allowed her to build — but so far, Webster has deftly navigated the music business without sacrificing her personality, her community or her privacy, and she doesn’t see that changing under Columbia. “I think throughout this process [of signing the new deal], I’ve been very up front and honest. I was like, ‘Don’t be surprised if I say no to a lot of things.’ I think being honest and having an understanding of each other is really important in any relationship.”

“I know it’s a buzzword, but Faye is just so relentlessly authentic,” says her manager, Look Out Kid founder and partner Nick O’Byrne. “Over the years, I’ve seen she’s not interested in doing anything that feels unnatural to her, and from talking to fans, I know that they’re smart and they see that in her, too.”

When I ask Webster if this signing is an indication that she is more comfortable in the spotlight now, she quickly replies “no” with a laugh. “I think I’m just always going to be this way.”

This story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

On a warm, breezy evening in Kyoto, Japan’s biggest music stars walked a red carpet, performed their most popular hits and thanked their fans as they took the stage to receive ruby-hued awards.The dazzling ceremony, which was televised across Japan May 21-22 and livestreamed on YouTube, felt in many ways similar to the Grammy Awards.

But remarkably, even though Japan is the world’s second-biggest music market, the inaugural Music Awards Japan (MAJ) marked the country’s first major national music awards show.

“We’re honored to have received an award, but I also believe this could become a goal for young people in Japan who are just starting out in music,” said Ayase, producer and member of Japanese duo YOASOBI, after winning the top global hit from Japan award. “I hope that through events like this, people both in Japan and abroad will come to appreciate the greatness of Japanese music even more.”

The glitzy new gala is core to Japan’s mission to turbocharge its export of music to the world. For years, its music industry was able to increase revenue by marketing to fans within its borders thanks to the country’s enormous appetite for physical products like CDs and vinyl, which still account for 62.5% of its overall recorded-music revenue, according to IFPI. But those days have come to an end: Japan’s population has been shrinking for the past 14 years — and has been slow to adopt streaming. The country’s recorded-music revenue fell 2.6% in 2024, even as global recorded-music revenue has grown for the last 10 years, according to IFPI. So, to woo a global audience, Japan’s major music trade groups representing labels, concert promoters, publishers, producers and other enterprises united to form the Japan Culture and Entertainment Industry Promotion Association (CEIPA) and organized the show, inviting guests from 15 countries to attend.

Nominees for most of the awards were selected based on chart data provided by Billboard Japan, and winners were determined by a two-stage voting process involving over 5,000 industry professionals.

Hip-hop sensation Creepy Nuts took home nine awards including song of the year for its viral hit “Bling-Bang-Bang-Born.” Singer-songwriter-pianist Fujii Kaze earned album of the year with his Love All Serve All project. Pop-rock band Mrs. GREEN APPLE racked up a multitude of honors including artist of the year. Kendrick Lamar, Billie Eilish and Ariana Grande won awards for the impact of their hits in Japan, though they weren’t present to accept in person. MAJ executive committee chairman Tatsuya Nomura says that CEIPA plans to host the next show in June 2026 at a bigger venue in Tokyo so fans and more international artists can attend.

One sign of this year’s success: Streams of songs that won top honors have jumped an average of 31% in Japan, with 21 out of the 27 songs that received top honors gaining streams compared with the previous week, according to Luminate.

This story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

At an invite-only, dimly lit vinyl bar just outside of central Tokyo, a handful of pool cues are framed above the table. Each has a nameplate, but only one name belongs to an American: Brandon Silverstein. The prime placement represents much more than billiards skill — it symbolizes the years of work, and ultimate partnership, between Silverstein’s entertainment company, S10, and the bar’s proprietor, Japanese entertainment giant Avex. In March, the two companies cemented that partnership with the launch of Avex Music Group, the rebranded U.S. division of Avex (formerly known as Avex USA), and Silverstein was named CEO.

Silverstein describes AMG as “a boutique major with a global perspective” — and that ethos is exactly what drew him to Avex five years ago. After he launched S10 in 2017 as an artist management firm, his friend and collaborator Ryan Tedder suggested he start a publishing company. “I was looking for a partner — and was looking for a different type of partner,” Silverstein recalls while seated in the fifth-floor lobby of Avex’s pristine Tokyo headquarters.

Trending on Billboard

In 2019, Silverstein was introduced to Naoki Osada, then-head of Avex USA, and the two hit it off. In 2020, S10 Publishing launched as a joint venture with Avex, and soon after, Silverstein flew to Tokyo for the first time to meet with Avex founder and chairman Max Matsuura and Avex Group CEO Katsumi Kuroiwa. “From the initial meetings, [we had] very similar visions, cowboy mindsets,” Silverstein says. Today, S10 Publishing’s roster boasts nine songwriter-producers, including Harv (Justin Bieber), Jasper Harris (Tate McRae, Jack Harlow) and Gent! (Doja Cat).

In May, AMG announced it had signed fast-rising producer Elkan (Drake, Rihanna) to a global publishing deal and partnered with the hit-maker on his joint-venture publishing company, Toibox by Elkan — the first, Silverstein hopes, of many such deals. “Artists are some of the most incredible entrepreneurs, and they just need an infrastructure, the right infrastructure, to have their ideas prevail,” he says. That thinking is Avex’s backbone: The company’s approach to creation, Kuroiwa says, is “entrepreneurship, since we’re an independent company — and we would like to remain independent.”

Most recently, AMG scored a major signing with We the Band, famously known as Bieber’s backing musicians (evidence, Silverstein suggests, of his theory that “artists are finding talent first”). He says S10’s relationship with the act dates to when it signed member Harv to a publishing deal in 2021; soon after, Harv scored a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 as a co-writer/co-producer on Bieber’s “Peaches.”

For Avex — known in Japan as the fourth major, alongside Sony, Universal and Warner — the early investment in S10 Publishing was essentially a down payment on global domination, the initial step of a five-year plan that culminated this year in AMG’s launch. (In conjunction with Silverstein’s new role, Avex acquired 100% of the S10 Publishing song catalog and an additional stake in S10 Management; Avex now has the largest share in S10 Management, alongside Silverstein and Roc Nation.)

Since its inception in 1988, Avex has always moved the needle, largely thanks to Matsuura’s singular vision and healthy relationship with risk. “When we started, we were laser focused on Euro-beat, a really small genre and market,” recalls Kuroiwa, who joined Avex Group in 2001 and became CEO in 2020. “[We did] stuff that other record companies wouldn’t choose to do, and that has shaped who we are today.” It’s even part of the company motto: “Really! Mad + Pure.”

“I don’t think I would be here today if Avex wasn’t that kind of company,” adds Takeya Ino, president of Avex’s label division, Avex Music Creative, which has a roster of over 500 artists. “It’s about creating a new movement, and that has always been the way at Avex: disco booms, Euro-beat, Japanese hip-hop. And then we think about what’s next for us — and the answer would be the global market,” adds Ino, who joined Avex in 1995.

Despite now employing around 1,500 people across offices in over 50 cities and earning $1 billion in 2024, the publicly traded Avex still has that small-but-mighty mindset that allowed it to become “a comprehensive entertainment company,” Kuroiwa says. “You see a lot of that nowadays, but we were the pioneers — one of the first labels to have an in-house management business, scout and train our own artists, produce and host live events.”

Those pillars still support Avex, particularly Avex Youth Studio, the intensive training program for potential future superstars where over 200 trainees are enrolled. Scouts regularly scour around 500 arts schools to identify talent; once selected, trainees aren’t charged tuition because Avex sees them as investments.

It was at Avex Youth Studio’s main facility, avex Youth studio TOKYO, in Tokyo’s Setagaya City, that, roughly four years ago, emerging Japanese boy band One or Eight was developed. For the past two years, Avex has been testing its next act, with the current top seven boys (ages 14-16) training together. The boys’ influences include Bieber, Kendrick Lamar, Ed Sheeran and Morgan Wallen; clearly, from the start, the goal is global success.

It’s evident in how Avex produces live events, thanks to AEGX, a deal made with AEG in 2021 that has brought superstars such as Sheeran and Taylor Swift to Japan for sold-out stadium shows. “Initially, [AEGX] was built to support the overseas artists that wanted to perform in Japan,” Kuroiwa explains. “But now we’re entering an era where Asian artists will perform and succeed overseas, which means there will be demand for both.” After helping non-Japanese stars book shows in Japan, AEGX can now help Japanese artists book shows in the United States and elsewhere. For One or Eight, Ino has his sights on New York’s Madison Square Garden.

From left: Neo, Mizuki, Takeru, Reia, Souma, Ryota, Tsubasa and Yuga of One or Eight during rehearsal at avex Youth Studio TOKYO.

OOZ

And much like how teaming with AEG helps Avex and its artists tour beyond Japan, partnering with Silverstein’s S10 helps Avex and its artists score hits.

One or Eight’s debut in August 2024 marked the first time an Avex act had U.S. management in S10 (co-managed with Avex). And in May, Atlantic Records and Avex partnered on all future releases for the group. “The staff that are involved in this project are from Japan as well as the U.S., and so we have this cross-border structure in place,” Kuroiwa says. “Visionwise, it really comes down to creating a successful case model. This whole project, the purpose is to have global hits — and not just one.”

The band’s credits exemplify one of Kuroiwa’s mottos: “Co-creation is key.” One or Eight’s debut single, “Don’t Tell Nobody,” was co-produced by Tedder, and Stargate produced its second single, “DSTM” (which prominently samples Rihanna’s Stargate-produced “Don’t Stop the Music” — the first time the hit has been officially sampled). “DSTM” also credits S10 songwriter David Arkwright, who co-wrote Riize’s “Get a Guitar,” which Silverstein says was an early win for the publishing company. (Riize is signed to SM Entertainment, which in 2001 partnered with Avex to launch the subsidiary SM Entertainment Japan.)

“Our writers are getting early access to placing songs for [One or Eight],” Silverstein says, adding that many have attended writing camps in Japan. “This is an ongoing [exchange] where we’re creating records that may work for our next boy group or girl group coming from Japan, or whatever the group is.”

Fast-rising Avex act XG — the first project under the XGALX brand, a partnership with executive producer Simon Park — also embodies Kuroiwa’s collaborative vision. The Japanese girl group, which is based in South Korea, debuted in 2022 and appeared at Coachella in April. “We’ve seen how K-pop players ventured into the global market, but we didn’t have the right Japanese talents to get on that bandwagon at that time,” Kuroiwa says. “It took us five years, also because of the pandemic, but we trained [XG] in studios, integrating the knowledge and expertise from our side as well as their side, meaning K-pop. What you get from that is something completely new.”

For Ino, the success of K-pop — which he says “built that pathway for foreign music to enter the U.S. market and to succeed globally” — is, in part, what made him confident that the world would similarly embrace J-pop.

He cites Japan’s “aging society” as one of Avex’s impetuses to take J-pop global, saying that in terms of growth potential, it’s a primary driver for needing to market outside of Japan. He also points to the sturdy U.S. infrastructure that Avex has built with S10 and beyond: “Everyone said that now is the time, there is an opportunity, there is a chance to really go into the U.S. market,” he says. “Maybe it was Ryan [Tedder] who accentuated that point the most — he said that now is maybe not the time for K-pop anymore. It’s really the time for J-pop.” But, Ino adds with a laugh, “he is working with HYBE anyway.” (In February, Tedder teamed with HYBE to form a global boy group that has yet to debut.)

J-pop is indeed its own world. To Ino, the umbrella term represents a “more diverse” class of music. “And there’s the anime, manga and V-tubers [viral YouTubers],” he adds. “We have all these categories that we can really leverage and take advantage of, so integrating them all together, it will be our forte.”

Now, with AMG, that integration will only grow. Following S10’s 2020 joint venture with Avex, the pair constructed a studio house in West Hollywood for events and to build a creative community. In April, AMG upgraded to a new, larger WeHo home that previously belonged to A$AP Rocky and Rihanna that will continue to be used for community-building, as well as housing Avex’s executives when they visit from Japan.

“Creatives are craving boutique companies that are fresh and exciting and are globally positioned, and I don’t think there’s a lot of that,” Silverstein says. “We want to back the artist’s vision and the writer’s vision and the producer’s vision and allow them to be their own CEO. I think that’s the change [we need] — and I think Avex Music Group will prevail because of that.”

As Kuroiwa and Ino see it, AMG will prevail because of the groundwork it has laid so carefully over the last five years. “[S10] really helped us in creating something new,” Kuroiwa says. “There were a couple of companies in Japan that [attempted this] in the past, but they couldn’t make it happen.”

To which Silverstein says with a confident smile: “We’ve got the right team. We’ve got the right relationships. We have the right partnership. We have the right vision. We have the right momentum. We’re ready.”

This story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

“When we first started taking the train in from Long Island, me and Biz [Markie] and the other Sixth Borough artists had to sneak into events like this and steal a mic to get onstage,” Rakim says. “Now we got the red carpet.”

The Wyandanch, N.Y.-born rapper, who inspired everyone from Jay-Z to Eminem with his culture-shifting rhymes as part of the duo Eric B. & Rakim, is talking about The Sixth Borough, a documentary about Long Island hip-hop that will premiere at Tribeca Festival on June 11, followed by a set from Rakim and De La Soul. It’s one of many music-centric movies playing at the event, which begins June 4 with the world premiere of Billy Joel: And So It Goes, a documentary that will screen weeks after Joel revealed that health issues were forcing him to scuttle all upcoming appearances.

Tribeca Festival director/senior vp of programming Cara Cusumano has watched its music-related programming steadily increase since joining in 2007 after attending the inaugural festival as a student in 2002 (“I always wanted to be involved in some way,” she recalls). This year’s lineup includes documentaries from Becky G (Rebecca), Eddie Vedder (Matter of Time), Billy Idol (Billy Idol Should Be Dead) and more. “At its core, our new film M is about the deep connection between music, culture, and people,” says Depeche Mode singer Dave Gahan of the concert doc Depeche Mode: M, which debuts at Tribeca on June 5. “Fernando Frías, who directed and conceived the film, did a beautiful job telling that story through the lens of Mexican culture and our shows in Mexico City. To now bring it to Tribeca and share it with a wider audience here is something we’re truly proud of.”

Trending on Billboard

“Our local audience is New York – it’s the biggest, most diverse moviegoing audience in the world,” says Cusumano of the festival’s appetite for eclectic stories. And as new media continues to redefine film, that diversity extends to the cinematic perimeters of projects on this year’s lineup, which includes visual albums from Miley Cyrus (Something Beautiful), Slick Rick (Victory) and Turnstile (Never Enough).

“The labels are giving more and more budget toward these visual albums,” says music programmer Vincent Cassous, who worked as a booking agent before joining the Tribeca Festival in 2022. “It’s a big swing for promo.”

Working with each film’s director and producer, Cassous helps execute what happens after the film wraps: A Q&A with Cyrus? A performance by Vedder? A house music party? “Obviously, production and budgets come into play,” he says, adding that the festival is committed to keeping ticket prices low even as production costs rise.

Those post-screening events often carry an emotional weight that even affects seasoned veterans. “I was backstage with Santana a couple years ago at the Beacon … his hand was shaking when he was introducing the [2023 Carlos documentary],” Cassous says. “This person has performed for millions of people, but I think for him, he was so vulnerable in the film and his whole family was there.”

“These people are often seeing films for the first time that are their own lives and careers calculated, and then getting up onstage immediately,” Cusumano adds. “It is such a unique moment in their lives that audiences get to be invited into.”

A version of this story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

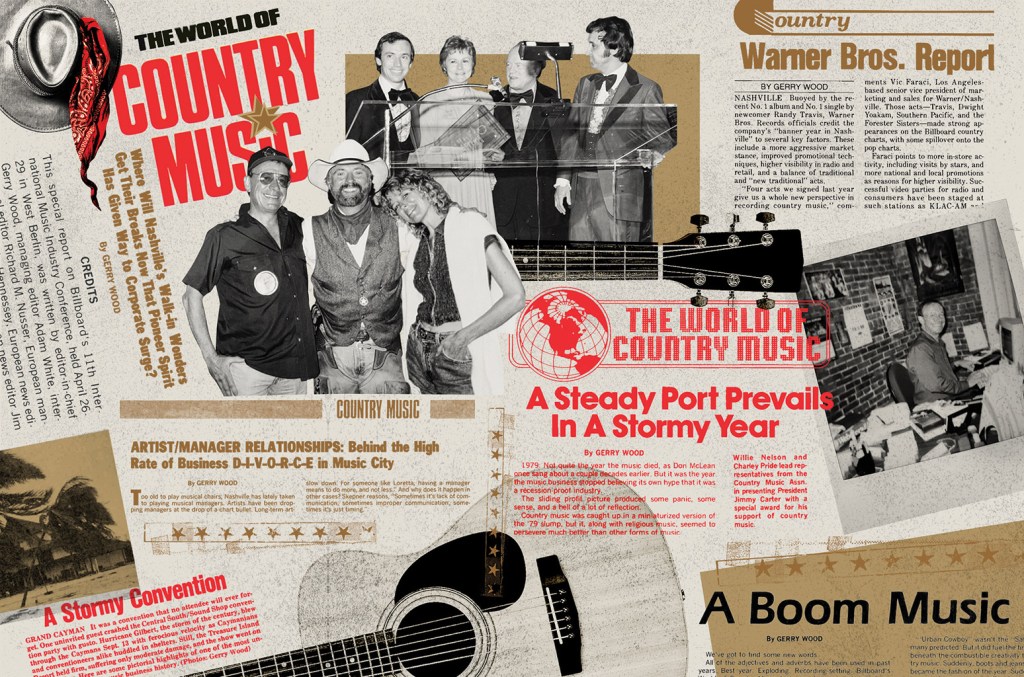

“Many Nashville publishers sold their firms, then cried swampfulls of crocodile tears all the way to the bank when they suddenly became multimillionaires.” That’s a 1988 hot take on country’s corporate makeover from Gerry Wood, a former Billboard Nashville bureau chief and editor in chief who passed away on May 3 at the age of 87.

Wood had worked in radio and PR before Billboard, and he was a character and the staff knew it. A 1988 retail convention photo identifies him as “Gerry Wood (back to camera — for a change).” From 1975 to 1991 — minus 1983 to 1986, when he worked elsewhere — Wood burned up the pages of Billboard with comprehensive reporting and crisp writing about country’s mainstream moment and how it changed Nashville.

Taking Root

“Country music has been spreading like kudzu,” Wood wrote in the Oct. 16, 1977, Billboard. “That’s the Southern vine that grows so fast it is rumored to be the cause of missing cows and pigs on Southern farms. Spawned in this fertile, blood-red soil of the South, this music has vined into the cities and countries where today’s frenetic, polluted environment grasps for something fresh, yet traditional. Often, that something turns out to be country music.”

Trending on Billboard

Head Games

This “was the year the music business stopped believing its own hype that it was a recession-proof industry,” Wood wrote in the Oct. 13, 1979, issue. Country seemed to fare better than other genres, though. “When CBS Records corporately cut some 300 heads, only one of those heads dropped in Nashville.” Some of that safety came from commercial crossover potential. “Lord knows,” Wood wrote, “if it keeps up, we’ll be seeing Gene Watson wearing KISS makeup with a flaming guitar.”

The Year Country Broke

“We’ve got to find some new words,” Wood wrote in the Oct. 18, 1980, issue, as Kenny Rogers and Urban Cowboy spurred a stampede toward Nashville. “All of the adjectives and adverbs have been used in past years. Best year. Exploding. Record-setting.” Not only had country “gone California and Texas and Tennessee,” Wood wrote, “it has gone Ohio and Canada and New York.”

Alphabet Soup

“Once upon a time Nashville was as easy as ABC. Now it’s as complex as SBK, BMG, TNN, CMT, WCI, and PolySomething.” So wrote Wood in the Oct. 15, 1988, issue. “The sleepy Southern village that gave America music from its soul in the ’50s and ’60s became the darling of corporate overtures in the ’70s and succumbed to the almighty dollar in the ’80s.” Even as Music City changed, Wood’s wit didn’t. “Too old to play musical chairs, Nashville has lately taken to playing musical managers,” he wrote in the same issue. “Artists have been dropping managers at the drop of a chart bullet.”

Next Big Thing

In the June 30, 1990, issue, Wood wrote a column “predicting the Roy Rogers of the ’90s.” His bets were prescient: Clint Black, Garth Brooks and Alan Jackson. One prediction, “country rap,” was decades ahead of the curve. But his crystal ball had one crack: “Willie Nelson’s Cowboy Channel will get off to a slow start, just like Willie did, but end up a winner, just like Willie did,” he wrote of Nelson’s planned cable network. It never even launched.

This story appears in the May 31, 2025, issue of Billboard.

It’s no coincidence that the two songs tied for most weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100 toe the line between country and rap. Lil Nas X set the record with his Billy Ray Cyrus-featuring “Old Town Road” in 2019, and late last year, Shaboozey tied the record when “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” hit the same 19-week mark.

“Country and rap might come from different worlds, but they thrive on the same foundation — raw storytelling and authenticity,” UnitedMasters director of A&R Aaron Hunter says.

Hybrids of country and hip-hop have a long history in popular music, dating back to the 1980s including hits like Sir-Mix-A-Lot’s “Square Dance Rap,” Kool Moe Dee’s “Wild Wild West” and Shawn Brown’s “Rappin’ Duke” (which The Notorious B.I.G. sampled in “Juicy” a decade later).

Trending on Billboard

This year has brought an even bigger boom of successful crossovers between the genres. Post Malone’s Big Ass Stadium Tour with Jelly Roll — two artists with roots in hip-hop now making country music — has so far featured special guests including Eminem and Quavo. Dallas rapper BigXthaPlug teamed with Bailey Zimmerman for “All the Way,” a top five hit on the Hot 100, while ERNEST and Snoop Dogg released their country collaboration, “Gettin’ Gone.”

On the festival front, the country-heavy Stagecoach was more rap-inclusive in 2025, with Nelly and T-Pain playing to major audiences. Meanwhile, Morgan Wallen’s Sand in My Boots Festival had Wiz Khalifa, 2 Chainz and Three 6 Mafia onstage.

“Both genres share the same theme of heartbreak, life stories and struggle, whether it’s rural life or urban hustle, and that grit creates a natural connection,” Hunter says. He also points to the rising use of trap drums and 808s in country and rap, which has “blurred lines, making collaborations feel less forced and more like a shared language.”

BigXthaPlug will follow the success of “All the Way” with a country-trap project this summer that will include guest appearances from Jelly Roll, Post Malone and Shaboozey. Even though the Dallas native never listened to country music growing up, he has felt a warm welcome from the Nashville community. “My fan base is the country world’s fan base,” he says. “They was messing with me, [but] now it’s a full acceptance.”

This story appears in the May 31, 2025, issue of Billboard.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio