Interview

Page: 2

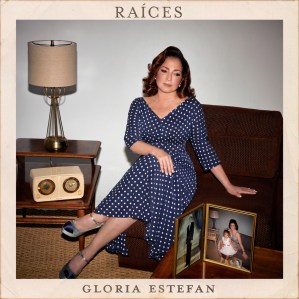

Gloria Estefan is ready to introduce the world to Raíces, her first Spanish-language album in 18 years and the 30th in her 50-year career. It is, in the words of the superstar, “like a modern Mi Tierra” — a sort of sequel to her iconic first LP in her native language, but freer.

“When we had the concept for the [1993] album Mi Tierra, we wanted to highlight a rich era of Cuban music that had been celebrated worldwide B.C. — before Castro,” the Cuban-American artist tells Billboard Español. “Back then, we were very careful to use the language that would have been used in the 1940s in the songs — the arrangements, the instrumentation, we kept it very much of that era. Here, we felt free to explore, always keeping family in mind and the music that gave us so much richness, and which helped us create these fusions, but coming from a very organic and real place.”

Set to release on Friday (May 30) under Sony Music Latin, Raíces consists of 13 tracks mostly written by musician and producer Emilio Estefan Jr., Gloria’s inseparable partner in life and career for over four decades. Salsa, bolero, and tropical rhythms resonate in songs ranging from previously released singles like “Raíces” and “La Vecina (No Sé Na’)” to deeply romantic tracks such as “Tan Iguales y Tan Diferentes,” “Te Juro,” “Agua Dulce,” and “Tú y Yo.”

Among the few songs penned by Gloria is the sweet “Mi Niño Bello (Para Sasha),” dedicated to her only grandson, with the English version “My Beautiful Boy (For Sasha).” “Since he was born, we’ve had a very beautiful and close relationship,” she proudly shares, adding that in Spanish she wanted to create something “with the flavor of ‘Drume Negrita,’ something very classic, a Cuban lullaby.”

A second song on the album, “Cuando el Tiempo Nos Castiga” (co-written by Emilio and Gian Marco and originally recorded by Jon Secada in 2001), also has a new English version courtesy of Gloria, titled “How Will You Be Remembered.” “I never translate exactly. I think about the feeling, the emotion, what one wants to express about the theme, and I approach it in the new language. In English, I was thinking more about legacy — you want to feel happy with what you left behind,” she explains about the discrepancy in the titles, with the one in Spanish meaning “When time punished us.”

Estefan — who in 2023 became the first Latina inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and in 2024 received the Legend Award at the Billboard Latin Women in Music ceremony — usually writes more for her albums, but this time she was focused on creating songs for the upcoming Broadway musical BASURA alongside her daughter Emily when Emilio presented her with the idea for the song “Raíces” a couple of years ago.

“Emilio didn’t even realize it was my 50th [career anniversary],” recalls Estefan, who wanted to do something special to celebrate the milestone. “I told him, ‘Babe, I can’t change my mindset for this, but I would like, if I do an album again, for it to be tropical, for it to be in Spanish.’ He says, ‘Do you trust me?’ I go, ‘Who else am I gonna trust than you?’”

Raíces is Gloria Estefan’s first Spanish-language album since 90 Millas, which debuted and spent three weeks at No. 1 on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart in October 2007. Mi Tierra, meanwhile, spent a whooping 58 weeks at the top of the chart.

Estefan also spoke about the new Pope Leo XIV, immigration, and more. Watch the interview in the video above.

Gloria Estefan, ‘RAICES’

Courtesy Photo

When Shamir first broke into music in 2015, the artist made a deal with himself: “Once I feel like I’ve done and said everything that I felt like I wanted to do and say, then I will call it,” he recalls. “I didn’t want to be an artist who was doing this just because it’s their job.”

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

One decade and 10 studio albums later, Shamir is making good on that promise. Ten, the mercurial multi-hyphenate’s excellent, indie rock-infused new album (out now via Kill Rock Stars) is his last one, too. Over the course of 10 songs, Shamir tackles big and small questions — the existential struggle with aging on album-closer “29” feels right at home with the simpler understanding of love lost on “I Know We Can’t Be Friends” — before closing out this chapter of his professional life.

As he tells it, the decision to walk away from music was easy, at least in part because he had already experienced the closest thing he’s had to a break between his projects. Since putting out Ratchet in 2015, Shamir has released new albums at almost a yearly pace, occasionally dropping two full LPs in a single calendar year. But after the release of his 2023 project Homo Anxietatem, the singer says he found himself in need of some time off.

Trending on Billboard

“I was producing with a friend, and we were just, like, throwing the ideas around. And all of a sudden I realized I didn’t have any plans to make an album. I didn’t even really have, like, songs or anything,” he says. “But I was like, ‘I want to work with you just because we’re friends.’ That didn’t end up working out with that person, but the idea of working with friends really stuck with me.”

It was a different mode of operation for Shamir. Since getting dropped by XL Recordings over creative differences shortly after the release of Ratchet, he’s largely self-written and self-released his own projects, occasionally teaming up with other indie labels to help bring his LPs to life.

That changed when the artist found a new home at Kill Rock Stars. Since signing with the label in 2023, prior to the release of Homo Anxietatem, Shamir says he no longer felt burdened by the expectations of doing everything himself. “To have that space and have that backing from the label gave me a little bit more clarity,” he explains. “Ending this chapter of my career felt like it came from a place of peace instead of frustration, which I love.”

Where other artists might use a final album to say all the things they’ve ever wanted to say in their music, Shamir didn’t have to do the same — he’d already shared his deepest thoughts through albums like Heterosexuality and Hope. Instead, he decided to draw his conclusions about working with friends to their eventual conclusion.

Every song on Ten, for the first time in Shamir’s career, are entirely written and produced by others. Whether he was asking his closests friends to let him sing a song they wrote or combing through those same friends’ unreleased demos to find songs he could perform, Shamir ended up with 10 tracks, written by and for others, now being interpreted through his own distinct artistic lens.

“I have so many incredible friends who aren’t necessarily songwriters by trade, yet are just incredible songwriters,” he explains. “I didn’t want them to write ‘a Shamir song,’ you know what I mean? I wanted demos and vault tracks tracks, and to metabolize those and bring them into my world and make them my own.”

A key example of the selection process, Shamir says, is the album’s opening track “I Love My Friends.” Back in 2021, Shamir received an email from his close friend Andrew Harmon, with the song’s title as a subject line and nothing but an MP3 in the body. Enclosed was the song, written by Harmon exclusively as a dedicated thank you to his close-knit circle for helping him deal with the death of his father.

“I remember listening to it, and by the end I was just in tears,” Shamir says of the song. “A dedication like that, unprompted and as a thank you — as opposed to just sending a thank you card or something like that — was just so beautiful to me.”

Another standout from the album, the heartbreaking “I Don’t Know What You Want From Me,” was written by Torres, who Shamir “wasn’t even particularly close with.” But when he presented them with the idea backstage at a music festival, they immediately said they wanted to send him a track. “[Torres] was literally on tour, and still sent me three demos,” he says. “That one was definitely the most shocking, just in terms of their enthusiasm for the idea.”

It’s for that reason that Ten plays out as a love letter rather than a farewell, where Shamir thanks the people who buoyed him in a turbulent career for a decade. It’s also why Shamir decided to release the album on May 19 — the one year anniversary of his debut album Ratchet.

“It was just like an extra kind kismet thing that I was able to add on to the triple entendre of it all,” he says. “It’s so rare when that happens, so when it does happen, it just feels so much like confirmation.”

As it turns out, having said everything he wanted to say in his career is just one of the reasons Shamir made the decision to call it quits after Ten. Part of the reason he relied so much on the support of his friends was simply because the music industry is a hard place to thrive, especially as a Black queer artist wanting to do something different.

Shamir qualifies that with the simple fact that “we made a lot of strides with queer people in pop music.” But after a certain point, the singer saw a pattern emerge, and it was one that he had no interest in adding to. “As a Black queer person, it’s not only hard to assimilate, but we are rewarded when we assimilate. We have to play the game to for survival,” he says. “In a lot of ways, I have suffered because I refuse to assimilate — but it was worth it for me.”

Sure, there are drawbacks that came with that: “I was not able to reach a certain level of mainstream success,” Shamir relents. But broad recognition isn’t the metric by which he chooses to measure himself. “Whenever anyone looks back on my career in five, 10, 15, 20 years from now, they’re going to be like, ‘Oh, but he never compromised,’” he says. “And I never will.”

Styles P has been one of the sharpest rappers in the game for the past three decades as a member of The Lox, along with his prolific solo career. In a recent interview, Styles P essentially ranked himself higher than Jim Jones and cited his body of work as proof.

Styles P was a recent guest on The No Funny Sh*t podcast hosted by Kenny “KP” Supreme & DP. The G-Host discussed a bevy of topics, including his alignment with his brothers from The Lox, his various health business ventures, becoming an elder in Hip-Hop, and life as it happens.

In a clip that began to buzz online, Kenny Supreme, who we should note is a Harlem native, floated the idea that the Capo Jim Jones would get Styles P out of here in a song-for-song VERZUZ-like battle. Holidays Styles, a battle-tested MC, met Supreme’s assertion head-on as any rapper would when it comes to their skill set.

“Me and Jim [Jones] ain’t in the same league,” Styles says, after telling Supreme that his opinion is incorrect in his eyes. “Me and Jim don’t do the same things. I’m a bar master. I’m a lyrical technician. I’ve been on joints with some of the best emcees in the world. [The Notorious] B.I.G., Hov, Black Thought, Talib [Kweli]. I bar sh*t down.”

Styles added, “If there is a lyricist or MC, I’m one of their favorites. I’m not here to make catchy hooks and do dope shit, I don’t know that. I’m into making your f*cking soul move.”

Styles P, along with Jadakiss and Sheek Louch, easily dispatched of Jim Jones and the Dipset collective in their explosive VERZUZ battle in New York that the culture still talks about with high reverence. Will this renew interest in a further battle? Will the Vamp Life honcho respond to Styles? Stay tuned.

Hop to the 23:00-minute mark to hear the discussion above.

—

Photo: Johnny Nunez / Getty

“

HipHopWired Featured Video

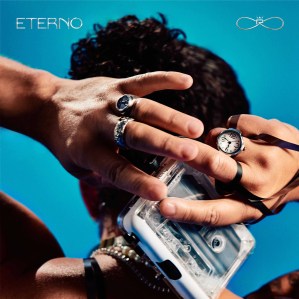

Fifteen years after achieving his first top 10 on Hot Latin Songs and his first No. 1 on Tropical Airplay with his take of “Stand by Me,” Prince Royce gifts his fans an entire album filled with pop classics in bilingual versions (English/Spanish) and bachata rhythms.

Titled ETERNO, the 13-track LP will be released Friday (May 16) under Sony Music Latin. It includes everything from “Dancing in the Moonlight” by King Harvest and “How Deep is Your Love” by the Bee Gees to “I Just Called to Say I Love You” by Stevie Wonder and “Go Your Own Way” by Fleetwood Mac, with “I Want It That Way” by the Backstreet Boys as the focus track. All the Spanish lyrics were written by Royce himself.

“For me, these are songs that are eternal, iconic, legendary,” the Latin star tells Billboard Español. “The intention with the album was somewhat similar to ‘Stand by Me.’ I wanted to bring back that nostalgia from a time when there was no Auto-Tune, when everything was raw, very real, into today’s world.”

Trending on Billboard

With a tracklist that also includes “Stuck on You” (Lionel Richie), “Right Here Waiting” (Richard Marx), “Can’t Help Falling in Love” (Elvis Presley), and “Yesterday” (The Beatles), Royce says it took his team about nine months to secure all the rights.

“When I was seeing that a song was going to go in, I was already like, ‘Okay, it fits in bachata,’” he explains about the selection process. “For me, the important thing was that the songs worked well in bachata, that the Spanish was good, that it flowed with the genre. Also I didn’t wanna force songs — it was important to keep the Prince Royce essence while also respecting the original song.”

Among the classics he felt were essential for this album, he mentions “Dancing in the Moonlight” as a song with a “positive vibe” that had always reminded him of bachata; “Can’t Help Falling in Love” as a perfect “wedding song” that was somewhat difficult to adapt; “My Girl” by The Temptations as an iconic “doo-wop” he wanted to tackle even though it reminded him of his previous hit “Stand by Me”; and “Stuck on You” by Lionel Richie, one of his personal favorites.

ETERNO follows Prince Royce’s 2024 album Llamada Perdida, a deeply personal set that included several heartbreak songs. This new project was very different, and Royce says he had fun learning and researching the original artists and embracing the challenge of adapting himself to their songs.

“It was just like a fun, music-geek project. I ended up really enjoying it and really like dissecting each harmony and background vocal and recording it,” he says enthusiastically. “I’d like for people who know these songs to bring those memories back, and maybe the younger generation in Latin America who doesn’t know them creates new memories. I hope we can achieve that.”

Prince Royce ‘ETERNO’

Courtesy Photo

Snoop Dogg has enjoyed well over three decades of notoriety and the requisite ups and downs that come along with fame. In a recent sitdown with The Breakfast Club, Snoop Dogg addressed fans who refer to him as a sellout over his assumed alignment with President Donald Trump, and he appeared to clear the record.

The larger part of the conversation centered on Snoop Dogg’s legacy as an artist, learning how to adjust to being a grandfather, praising his wife’s guidance for his family, and promising some new music down the pipeline, including his upcoming 21st studio album, Iz It A Crime? He also spoke on Warren G, a past collaborator of both Snoop and Dr. Dre, who felt like he was left out of the Missionary album sessions with his past partners.

From there, the conversation shifted to Snoop’s appearance at the Crypto Ball around the time of President Trump’s inauguration. The Doggfather was blitzed by fans who felt that he betrayed them for doing the event, considering some of the president’s current political positions. Snoop was clear to draw a line right there.

“Can’t none of you motherf*ckers tell me what I can and can’t do,” Snoop said after explaining he DJ-ed a set at the event for 30 minutes. “But I’m not a politician. I don’t represent the Republican Party. I don’t represent the Democratic Party. I represent the motherf*cking Gangster Party period point blank, and G sh*t we don’t explain sh*t so that’s why I didn’t explain. That’s why I didn’t go into detail when motherf*ckers was trying to counsel me and say he a sellout.”

Snoop went on to say that he would frequently post certain things on his popular Instagram page to see what fans had to say, with some using keyboard courage to call the veteran rapper out his name. Snoop said he hopped into some DMs and addressed the critics head-on, confirming that everyone changed their tune after that.

Check out Snoop Dogg’s full chat with The Breakfast Club in the video below. Hop to the 21:00-minute mark to see the topic mentioned above.

—

Photo: Screenshot / YouTube/The Breakfast Club

HipHopWired Featured Video

Yeri Mua, the Mexican influencer who became TikTok’s No. 1 most-viewed musical artist globally in 2024, officially releases her debut album under Sony Music México, De Chava, tonight (May 15).

“It’s an album that totally captures my essence, who I am as a person,” the 23-year-old artist tells Billboard Español. “I’m not that grown-up, I’m young, but I’m at that stage in life where you start to understand many things — even though I never stop having fun, enjoying myself and falling in love. Literally, it’s about chava (girl) things.”

The 15-track set — which includes previously released singles like “Traka,” “Croketita” with La Lokera, “Avión Privado” with El Malilla, “Él No Es Tuyo” with Bellakath and Uzielito Mix, and “Modo Antidepresivo” alongside Snow The Product — arrives with the focus track “Morrita (Tinker Bell),” a song featuring Chilean artist Lewis Somes, in which she sings to an ex that he’s already lost her, and that he doesn’t have a brain.

Trending on Billboard

Produced (among others) by SAAK, Uzielito Mix and Jocsan La Loquera, it also includes collabs with La Joaqui (“Salida de Chicas”), Chris Tales (“Viña Mari”), and Marcianeke (“Combi”) — all with very colloquial and explicit language.

Yeri Mua signed with Sony Music México in mid-2024, when she was already amassing more than 600 million streams of her solo music and collaborations, according to a statement issued by the label at the time. From giving beauty tips and undergoing a remarkable physical transformation to becoming one of the top “reggaetón Mexa” performers, she is now entering a new phase in her rising career as a singer.

“I feel very proud of what I’ve achieved so far, much more confident than ever — and above all, deeply in love with what I’ve created with Sony Music — so, I’m ready for whatever comes next,” she says in her signature carefree style.

After a series of performances in the U.S. and Costa Rica, Yeri Mua is preparing for an important milestone in her career: her first solo concert in Mexico City, scheduled for May 30 at the Pepsi Center. She will then take her Traka Tour to other Latin American countries, including Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Guatemala.

But today, as De Chava is being released, she reflects on her beginnings, opens up about her fears, and looks forward to the future.

As an influencer, you were used to everything happening quickly. The process of building a career as a singer is different. How have you handled that?

I’m not going to lie, it’s been a very long process — because, obviously, things happen along the way. I even questioned myself about whether I really wanted this, and I lost a bit of motivation. But ultimately, here I am, happy.

How do you feel after transitioning from influencer to singer?

It was difficult, because now I have to earn people’s respect as an artist. Sometimes I even felt embarrassed to say I was a singer — but I am, and I’ve learned to believe in myself and trust in my ability to make this work. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t be here facing this head-on. I haven’t stopped being who I was — in fact, the album talks a lot about beauty, wanting to look spectacular, the things I enjoy doing, and what I love. I think many people can relate to my songs, regardless of their age.

I’m aware of my privilege, and I think there’s nothing wrong with that. Obviously, an influencer lives much more comfortably than most ordinary people who earn a minimum wage and work long hours. Yes, it’s a privilege to dedicate yourself to social media, but it’s not easy — it’s taken me a lot of effort to get to where I am; I’ve worked hard for this. I worked other jobs before becoming an influencer. Being an influencer was like a period of preparation for what God had planned for me.

Now as a singer, what’s your opinion about this profession?

My dreams have materialized, and it’s largely thanks to my team. An artist can’t achieve something like this alone, so I’m grateful and happy to have them.

There have been restrictions in many Mexican states on narcocorrido singers because of the lyrics. Are you prepared if this happens with reggaetón?

I think it was somewhat logical that this would happen with regional Mexican music because of words connected to drug trafficking. As for reggaetón, I don’t think explicit words will be censored. They might make some people uncomfortable, but they don’t offend or harm anyone.

Your upcoming Latin American tour is another big step forward in your music career.

I did very well on the tour I did in the United States, as well as in Costa Rica. Now it’s time to visit my fans in several countries, and I want to thank them for their support — so I’m going to give it my all.

Southern California has long been shaped by the essence of Chicano and cholo culture, a deeply ingrained presence that speaks to the region’s multifaceted identity. Murals and tattoos served as canvases for a range of imagery steeped this subculture — from low riders and clowns to the iconic “smile now, cry later” masks, while vending machines once dispensed prismatic stickers featuring cholas, homies, and pachucos, each paired with the name of a classic oldies song.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

At swap meets and once-thriving CD stores, Lowrider Oldies compilations where the backdrop to nights spent cruisin’ in custom lowriders outfitted with hydraulics — at quinceañeras, damas and chamelanes arrived in similar old school cars to these. This rich tradition boomed as Black and Brown culture intertwined, with the soulful sounds of Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson and Brenton Wood echoing across the hood.

Trending on Billboard

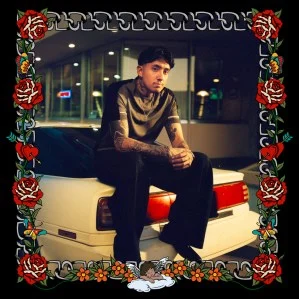

For Cuco, the 26-year-old singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist hailing from Hawthorne by way of Inglewood in L.A. county, this kind of environment shaped him. With his third studio album Ridin’, out Friday (May 9) — his “love letter to L.A.” and Chicano car culture — the artist reimagines oldies music through a modern lens, blending analog and harmonic richness to bridge generations while honoring his roots.

“The association with oldies and cars is a big thing here [in L.A.],” Coco tells Billboard Español. “I don’t know if that’s culturally relevant for the rest of the world, but I wanted it to be a thing [with my album].” He mentions that each of his upcoming visuals, for singles link “Phases” and “My 45,” will be paired with a classic car. “Obviously, this is my love letter to L.A., but I wanted it to be something that feels like it can be everywhere,” Cuco notes.

From the shimmering stylings of boleros to modern interpretations of timeless soul, Ridin’ unpacks emotion and tradition, making connections between collective nostalgia and personal experience. “[That influence] has always been there,” Cuco explains.

He adds, “There’s a lot of norteño culture out here in L.A., but also cumbias, románticas, and boleros. There’s a different part of Mexican culture blowing up, and oldies have always been around. They influenced a lot of the romantic part of my music. Many people don’t really know that. But there’s a lot of layers to me. I wanted to make an album that felt more old school.”

One of the defining cuts — of the album produced by Tom Brennick (Amy Winehouse, Mark Ronson, Bruno Mars) and mixed by Tom Elmhirst (Adele, Frank Ocean, Travis Scott) — is the title track. “’Ridin’’ was the first track that we worked on for this record, the first that Tommy made,” Cuco says. “I wanted it to feel like a nursery rhyme. There’s also that psychedelic break at the end.”

Other songs like “ICNBYH” (short for I Can’t Ever Break Your Heart) showcase the singer-songwriter’s knack for crafting infectious, big choruses that leave a lasting imprint on listeners. “The chorus feels timeless, and I really wanted to lean into my vocals,” Cuco explains. “For a lot of my older fans, it’s something that would be easier to digest before going into the rest of the album.”

His love for brown-eyed soul also shines in “Para Ti,” a Spanish-language ballad á la Ralfi Pagan. “I think my pen in Spanish is strong,” he shares. “It’s something that comes naturally. It feels like a mix between a bolero and a romántica, that I listened to a lot [too].” It’s the only song in Spanish on the album, but Cuco has also teased a deluxe version with additional tracks en español as currently being in the works.

In addition to nods to old-school greats like Barbara Lewis, including an interpolation of Lewis’ enduring ’60s hit “Hello Stranger” in “Seems So”, Cuco says that “Ralfi Pagan and Joe Bataan were on repeat a lot,” along with Smokey Robinson, Al Green and Brenton Wood. He also acknowledges newer artists blending vintage sounds with fresh perspectives, such as Thee Sacred Souls, Thee Sinseers and Los Yesterdays: “I got to work with some of those folks and meet really cool people that I look up to in that world. It was really dope.”

Emotionally, one of the album’s most striking moments comes in “My Old Friend,” a gently wistful ballad that Cuco describes as his way of connecting to life’s losses without falling into sorrow: “I wanted to write [a song] to the people that have passed away in my life. It’s something that I can still celebrate with the people that are alive around me. My cousin, who was there when I wrote the song, said, ‘Why does it feel sad, dude?’ I was like, ‘It’s not supposed to be.’ But it can be, depending on who you’re thinking about.”

Then there’s “My 45,” the only collaboration on the album. “I don’t generally work with a lot of songwriters, but for this record, a good chunk of the song is with my friend, Jean Carter,” he explains. “That’s my brother right there. We played it at the El Rey [in L.A.] at the live show, and people are geeked over that track.”

Ridin’ not only aims to connect generations through its music but also celebrates the evolution of a culture that remains alive. Or, as Cuco says: “It brings you into the world of the new oldies.”

Cuco

Courtesy Photo

After winning the Latin Grammy for best new artist in 2024, Colombian singer-songwriter Ela Taubert finally released Preguntas a las 11:11, her debut album, on Friday (May 9). The 16-track set, which took two years to bring to life, is a reflection of her deepest thoughts and her tendency to overthink.

All the song titles are framed as questions except for one, which is simply titled “Pregunta” (Question) and is the 11th track on the album.

“I’ve always overthought things since I was little, and that hasn’t changed now that I’m an adult,” explains the 24-year-old artist to Billboard Español. “When I started writing [these songs,] I realized all that came out were questions, which I think reflect my tendency to question everything. Obviously, when all the songs started to have this kind of title, we said, ‘Well, it’s going to be Preguntas, and a las 11:11 (at 11:11) because at home we always make a sacred wish at 11:11. So we unified these two universes.”

Trending on Billboard

Sonically, Taubert says that for this album — released under Universal Music Latina and featuring the singles “¿Cómo Pasó” (with and without Joe Jonas, and in a third live version with Morat), “¿Quién Diría?” and “¿Cómo Haces?”, among others — she drew inspiration from the pop superstars she grew up listening to.

“I used to watch the Hannah Montana movies. I literally wanted to be like that, a pop star. I’d wear sparkly gloves and everything,” she says enthusiastically. “Maybe I’m still holding on to that childhood dream of bringing the sound of the artists I listened to as a kid, like Miley [Cyrus], Taylor Swift, and Adele, to our language, Spanish — obviously while keeping my Latin roots super present, because I also grew up listening to Reik and Jesse & Joy. So I’d say it’s like a fusion.”

Designed to be listened to from start to finish, the LP weaves a narrative that feels both intimate and universal, addressing themes like love, heartbreak, and the complexities of human connection in songs like the focus tack “¿Trato Hecho?” as well as “¿Es En Serio?”, “¿Te Imaginas?”, “¿Qué Más Quieres?”, “¿Si Eras Tú?”, and more.

“This album is like a midnight diary for me. It’s about those moments when there’s no TV, no phone, nothing, and you can’t sleep, so you start thinking about 45,000 things at once,” Taubert summarizes. “I hope that the people who listen to me, who support me, find refuge in each of these songs and see themselves reflected in them. That’s been one of the most beautiful things about these last two years — growing the family, realizing I’m not the only one who feels the way I feel, and learning to grow together through this whole process.”

Below, Ela Taubert breaks down five essential tracks from Preguntas a las 11:11. Listen to the full album here.

“¿Quién Diría?”

Contextually, the album as a whole is a love story with all its ups and downs and emotions. But “¿Quién Diría?” (Who Would Say?) is precisely the track that starts it all. It’s the only love song on the album, so it opens up this universe and speaks about the first time I truly felt I was in love. I was always very rebellious about that kind of thing on a personal level — like, “I’m not going to fall in love, I’m not in love, I don’t like anything romantic.” And in the end, I fell in love, and that’s how the story begins. That’s why it’s so special, because it opens up this world. And also because fans were always asking me, “When are you going to release a love song?” So it’s like giving them a little taste of the fact that love has existed in my life — and it still does.

“¿Cómo Pasó?”

I think this was one of the most fun songs to make and also one of the quickest. It’s about my first heartbreak as a teenager, the first time I felt like my heart was broken. But it’s very beautiful, because when we started writing it — obviously I’m in a different place now. The idea behind this song was that I wanted people to feel exactly what I felt during that strong heartbreak. I wanted to share how I truly felt. That’s why at first it gives you the sense that it’s a love song — just like how I felt when I got my hopes up — and then suddenly, your world falls apart and you think, “Wow, this is a heartbreak song.” I wanted to allow people to navigate that emotion with me, the way I felt that intense disappointment.

And the twist with Joe Jonas — well, that was a dream come true for me. Joe was one of my childhood idols. I think he was for everyone, honestly, for people who watched Camp Rock and all those kinds of childhood series. It was a blessing, and I’m proof that dreams really do come true. Right when I got nominated for the Latin Grammy, I decided to look for a video of myself as a little girl singing, and I found one of me singing “This Is Me” from Camp Rock. So I wrote him thanking him for inspiring me, and then it was crazy, because a few days later, he replied — which blew my mind, because I never thought he’d reply. And the rest is history. This version is something I’ll carry in my heart forever, thinking about how it fulfilled my inner child’s dream.

“¿Cómo Haces?”

This is a very special song for me. It’s track No. 7 on the album because, for me, 7 is the number of my family. Everything has its reason. I wrote it for my mom, because my mom has been my anchor and my grounding force — she’s always there. It’s a very beautiful song, and I also realized it’s a song for all the people who’ve been there for me — the fans, everyone. So when we announced the album, the most beautiful way to do it was paying homage to her, to my whole family, my friends, and everyone who’s been there. That’s why, at the end of the song, during last year’s tour, after 40 attempts during the show in Bogotá where my mom was, where the fans were, everyone learned the song and we were able to record them and include them in the song [with a live snippet at the end].

“Preguntas”

Well, “Preguntas” (Questions) is the epicenter of the album. “Preguntas” represents where I’m at in my life right now on a very personal and emotional level. It’s the 2.0 version of a song I wrote for my first EP called “Crecer”. It talks about that difficult moment I experienced back then, about how hard I found it to grow up. I left my country alone at 18 or 19. It was really hard for me as an only child. So this song is very special to me, and honestly, “Preguntas” feels like the answer, almost three years later, to what I’m living now and how I see growth now. The fans will understand it deeply because they know what this symbolizes for me. That’s why it’s the 11th track, because it’s the most vulnerable part of me, and it’s the epicenter where questions are born.

“¿Trato Hecho?”

This is one of my favorites. To me, writing music is immortalizing memories, but this song specifically — the lyrics teleport me over and over again to that same place and bring me so much peace, for some reason, [even though] is a super sad song. Sonically, it’s one of the ones I feel most proud of as well, in the sense that I was able to pour all the emotions I felt in that moment into the song. That’s why it’s the focus track and why it’s the third track — it connects the whole story of the album very well. It’s been one of those promises, so to speak, that I’ve broken. It’s like a trato hecho (done deal) that we wouldn’t see each other again, but we saw each other again and tried again.

HipHopWired Featured Video

Kai Ca$h first appeared on our radar by way of his excellent 2021 album, 711 (Deluxe), and has been featured on past CRT FRSH (Certified Fresh) playlist roundups. The Brooklyn native spoke with Hip-Hop Wired about his persistence and consistency as an artist, which has positioned the humble and talented rapper’s career to soar even higher.

Kai Ca$h took time out of his busy recording schedule to talk with Hip-Hop Wired about his early beginnings, finding his voice as an artist, and where he hopes to take his craft now that he recently signed a deal with the stacked Generation Now collective founded by DJ Drama and Don Cannon and distributed by Atlantic Records.

For Kai, his current position was something he honed in on early on.

“I was born into music, and it’s what I’m most passionate about,” Kai explains, adding, “I never really gave myself a second option when it came to what I wanted to do in life. I’m really proud of that because I put my blood, sweat, and tears, everything I have, all into the music.”

Kai credits his mother’s diverse ear for music for increasing his palate as a listener first. His father was a close friend of The Notorious B.I.G. and a member of Junior M.A.F.I.A., giving a young Kai access to meet buzzing rap stars such as Lil’ Kim and Lil Cease, among others.

“Just being around those types of environments and that energy and then going back home with my mom listening to music, it just reassured me that this is the thing I wanted to do,” Kai said.

As mentioned above, Kai’s 711 (Deluxe) was a wider introduction of his sound after dropping his debut in 2019, and he shared what his journey was like between that project to his latest project, CASH RULES.

“At that time [during 711], I was independent. Being an independent artist is one of the hardest things ever, ” Kai shared. “I champion every independent artist that figures it out and develops a system that works for them because you might not see any money from it in a long time.”

Surprisingly, Kai revealed that he was shy and reserved, but the independent grind motivated him to work on his craft and transform his timidity into the ferocity fans witness now during his energetic live performances. He recently performed at this year’s Dreamville Festival alongside his longtime collaborator and friend, Niko Brim, who also hails from Hip-Hop royalty.

Source: Kai Ca$h / Generation Now/Atlantic Records

Our conversation with Kai moved to CASH RULES, his first body of work under the Generation Now imprint. Clocking in at 10 tracks, CASH RULES covers several lanes, including soul sample-driven beats, songs for “outside,” and plenty of moments of self-reflection. Don Cannon’s guiding hand opened the way for production from notable names like Bink, 2forwOyNE (Jack Harlow), Buddah Bless (Travis Scott, Megan Thee Stallion), and more. However, Kai’s already sharp and focused delivery sounds immediately improved.

“I still have a lot of work to do,” Kai said, not content to rest on recent successes. “I feel like a freshman walking through these doors. It’s just as important as everything I did before, and in some sense even more, because now I have eyes on me and a different kind of pressure. But this has been my dream since a kid, so I don’t feel any pressure at all.”

Check out Kai Ca$h online on Instagram here, and keep up with his movement on his site here.

—

Photo: Kai Ca$h / Generation Now/Atlantic Records

Global-facing J-pop group f5ve (pronounced “fi-vee”) may be riding the new wave bringing Japanese music to the world, but the rising five-piece are anything but rookies.

The members each have at least a decade of experience working in the music industry: Sayaka, Kaede, Ruri and Miyuu (ages 28-29) were in LDH Entertainment groups E-girls and Happiness, while 21-year-old Rui is still currently a member of iScream, under the same label. Recently, though, they’ve been taking stock of where there’s room to grow, from English fluency to the basics of recording and performing with a mic. (In J-pop groups, it’s normal to have dancers who don’t sing.)

That’s because, unlike their other projects, f5ve’s expressed mission is to make “Japanese pop music for an international audience,” which also means challenging stereotypes about what sounds the island nation produces. “I think people abroad think J-pop is all anime songs,” Kaede tells Billboard in English from a conference room in Tokyo. “Of course, we have a lot of anime songs,” she adds, “but not just those. We have cool songs; we have different genres of J-pop.”

Trending on Billboard

Their debut album, SEQUENCE 1, helmed by executive producer BloodPop (Justin Bieber’s “Sorry,” Lady Gaga & Ariana Grande’s “Rain on Me”), makes good on the goal of subverting expectations and bending genres to their will. Tokyo rave beats (“Underground,”) intergalactic hyperpop (“UFO,” co-produced by A. G. Cook,) and sleek runway stompers (“Television”) supplement high-energy, anime-theme-ready J-pop (“リア女 (Real Girl),” “Jump.”) Meanwhile, the music video for bass-heavy trap banger “Sugar Free Venom,” featuring Kesha, self-referentially nods to their previous life as members of E-girls — while simultaneously paying tribute to Beyoncé and The Pussycat Dolls.

They’re likewise meeting global fans where they are — namely, social media, on which f5ve unseriously ask artists for collabs and sport “flop era” tees. “Some people say our account seems unofficial,” Miyuu says, speaking about the brand of cheeky, chronically online posting that their socials engage in. “There’s no other group that has done it like this before. I think that’s what makes people so interested in us.”

Ahead of the release of SEQUENCE 1, out now, f5ve opened up about “fresh” experiences in the studio and their master plan to connect with listeners all over the world.

Billboard: How did you react when your agency approached you about being in a global group?

Kaede: We couldn’t believe it, because we have been doing this job for over 10 years. We built our careers in Japan, but we felt like we could expand more to the world.

Was there anything that scared you about the new group?

Miyuu: At first, honestly, I was scared. All the members were the same, I think. Kaede, Sayaka and I — in our previous group, we had never tried vocals. This group was the first time I tried to sing.

When did you start working on SEQUENCE 01, and what was the process like?

Kaede: We’ve been working on this album for about two years. So now it feels like… finally. When we were in the studio with BloodPop, we discussed what music we like and listen to. Then he created music from that conversation. He actually loves Japanese anime — us too. While we were talking about our favorite anime, he said, “Why don’t we try to make a song that has anime themes?” That’s how “リア女 (Real Girl)” was born. It was a fresh experience for us, because it was very different from how Japanese people create music.

How does that usually go?

Kaede: Producers bring us the [completed demo].

So this way, it was more collaborative?

Kaede: Yes. He always includes our ideas for f5ve’s music.

What are some of your favorite anime series? Which did you take inspiration from?

Miyuu: Oshi no Ko and its theme, “Idol” by Yaosobi. We texted him so many.

Rui: My favorite anime are My Hero Academia, Tokyo Ghoul and Kakegurui.

Is there any advice that BloodPop gave you while recording that stuck out to you?

Rui: There isn’t one comment from him, but when we were in the studio with him, [he asked which version of demos we prefer.] It’s so fresh for me. We can have our own opinion and tell him about what we think.

Kaede: When we were recording, BloodPop and our creative director said to me, “More b–chy, more slay,” because my personality and my voice are so energetic.

Are there other ways you feel like your on-stage personas differ from who you are in real life?

Kaede: I’m a totally different person. On stage, I have confidence and I can be more…slayish?

Miyuu: It’s kind of the same for me. Off stage, I’m not outgoing, and I can be pretty shy. But when I perform, it’s like “Look at me, look at me.” [Laughs]

One of f5ve’s goals is to “eradicate self-doubt,” but we all have moments of insecurity. How do you overcome that yourselves?

Rui: We have a lot of practice being on stage and shooting. f5ve is the best team, so I always trust the members, trust the staff and trust myself. And I can be natural, be positive.

Kaede: We compliment each other before we go on stage, always.

Miyuu: “You look so cute. You look so pretty. You look so gorgeous.”

Rui: “Beauty! Sexy!”

What compliment would you give to the person sitting next to you right now?

Kaede: Miyuu is our number one face expression queen.

Miyuu: Sayaka is one of the smallest members, but the way she performs and her aura make you feel otherwise.

Sayaka: Rui is a true idol. She has perfect expressions and is always on point on stage.

Rui: Ruri has… face card. Always beautiful. I’m also addicted to Ruri’s powerful voice. And she is so kind.

Ruri: Kaede is the sunshine of the group. She’s always talking to people, always communicating.

In the music video for “Magic Clock,” there were child dancers who played younger versions of you. Some of you have been in the entertainment industry since you were around their age, so did you have any advice for them?

Rui: They were so nervous during the music video shoot, so we were always by their side. [We told them,] “You are so cute, your dancing is so amazing. Please have confidence.” We gained power from them. I think that situation was my dream come true. I was so happy.

Why was it a dream come true?

Rui: I was a student at [Japanese entertainment training school] EXPG starting at a young age, and during that time, I looked up to E-girls and all the LDH groups.

Besides Kesha, who features on “Sugar-Free Venom,” which artists do you hope to collaborate with in the future?

Rui: I want to collaborate with Addison Rae someday. I love her music videos and her vibes. I’m a huge fan.

Sayaka: I want to collaborate with Tyla.

Miyuu: I love Doja Cat. [Her music embodies] woman empowerment, which is why it matches us.

Kaede: I want to collaborate with Justin Bieber. I’ve been a huge fan of his since I was a junior high school student. He was my first celebrity crush. [Laughs.] I love his voice, I love his music.

Ruri: Taylor Swift. I recently listened to The Tortured Poets Department, and that got me into her.

You also worked with producers like A. G. Cook and Count Baldor on SEQUENCE 01. Who would you love to have write or produce a song for f5ve in the future?

Rui: Of course, I want to create more music with BloodPop, but I want to collaborate with Zedd.

Kaede: I want to collaborate with ASOBISYSTEM in Japan. We saw ATARASHII GAKKO!’s show in LA, so I hope ASOBISYSTEM or Nakata Yasutaka creates our music with ATARASHII GAKKO!

The video for “Underground” had Dekotora trucks and Para Para. What other elements of Japanese culture do you want to share with the world?

Kaede: Natsumatsuri is a summer festival in Japan, and when I was a kid, I practiced and played traditional drums in the festival. So, one day, I want to show you my drum skills in our songs. I can surprise people abroad with that.

Rui: I want to wear a kimono or yukata in a music video or a live show.

The J-pop industry used to be pretty much exclusively interested in the Japanese market, but now we’re starting to see that open up. Why do you think that is?

Miyuu: Lately, I’ve been feeling that the international reception of J-pop is starting to shift. In the past, there weren’t many chances for people to get exposed to J-pop, so the Japanese music industry mainly focused on the domestic market, as you said. But I believe digital culture has played a huge role in introducing J-pop to a global audience.

How does f5ve plan to reach that audience?

Rui: Being natural and being ourselves. Just having fun with our music, loving our music. And each other.

Miyuu: Social media is a very important tool for us. It’s a space where we can really connect with our fans and make them feel close to us. We react to a lot of comments, responding to what fans are curious about. Some people say our account seems unofficial, in the best way. And there’s no other group that has done it like this before. I think that’s what makes people so interested in us.

Since you brought up social media, who is the most online in f5ve?

Miyuu: Rui’s always on her phone, taking selfies.

Kaede: During lunch, during dinner…

Rui: I love searching for TikTok trends.

Is anyone never on their phone, and has no idea what these trends are?

Kaede: Ruri. She could live without her phone.

What did you learn about yourself while making this album?

Kaede: I’ve learned from BloodPop and A. G. Cook that work is not just work. They said not to forget to bring a playful mind to it, enjoy the moment and put yourself into creation.

Sayaka: In my previous group, I was a performer, so I never had a chance to sing. While recording, I discovered what I can express to the world with my voice. I found my new power.

What is still on your bucket list as a group?

Kaede: I want to attend Billboard Women in Music, because recently I saw JENNIE and aespa attend. One day, we want to go and represent Japan.

Rui: I love anime, and our members like anime too, so one day we want to have an anime theme song.

Miyuu: I want to make a role-playing game where we each create our own weapon.

What would everyone’s weapon be?

Rui: Noodle slasher! I eat noodles every day.

Kaede: My big voice.

Miyuu: Lipstick sword, because I love makeup.

Sayaka: Bomb. [Members laugh.] I always say something awkward in conversations and it’s like a bomb.

Ruri: My long hair, like a whip.

Any other bucket list items?

Ruri: Attending Coachella.

Sayaka: I want to meet fans all over the world.

Is there a world tour in the works?

Kaede: There isn’t a date decided yet, but we’re planning.

Rui: Soon!

Kaede: Yes, coming soon.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio