From the Desk Of

Trending on Billboard

Over her 20-plus-year career, Tracy Gardner has seen her fair share of technological disruptions in the music business. “I started right when illegal downloads took over,” she says of her entry into the industry as an intern at what was then Warner Bros. Records (now Warner Records).

As TikTok’s global head of music business development — a position she has held since February — Gardner is now running point for the biggest disruptor of the industry over the last five years. The Brooklyn Law graduate, whom ByteDance recruited in 2019 after six years in the legal affairs and business development departments at Warner Music Group, took over from Ole Obermann — whom she also worked with at WMG — when he departed for Apple Music.

Related

In her new role as the platform’s chief liaison with the music industry, Gardner oversees deals with labels, publishers and the TikTok commercial music library and works closely with the platform’s strategy, finance, artist services, product and ad sales teams.

Her promotion comes at a fitful moment for TikTok, as ByteDance and the Trump administration are reportedly finalizing a deal that would result in a consortium of U.S. investors acquiring a majority stake in the app. Gardner was not able to comment on that process or how it might affect her division. But in this interview — her first since assuming her current role — she asserts that nearly two years after Universal Music Group temporarily pulled its artists’ music from TikTok over a breakdown in licensing negotiations, and the social media platform shifted label licensing away from Merlin, which licenses digital companies on behalf of over 30,000 indie labels and distributors, “We’re in a great place with the music industry. It’s a dynamic partnership that, as TikTok evolves quickly, has an impact on how we’re looking at deals, how we work with partners and what they want to get from a partnership with us.”

At Warner, you were on the other side of the negotiating table with ByteDance. How did that experience affect how you conduct your job now?

Mainly, it was great to come from the perspective of being at a label and a rights holder. [TikTok] was still relatively new when I got there, and we had to build the infrastructure and collaborate with other teams at ByteDance. A lot of our music team came over from either other DSPs [digital service providers] or labels, so there was a very good base to help the product teams, who don’t have music experience, understand what these rights holders expect from tech partners and what their artists are looking for.

What did you learn from watching Ole Obermann?

Ole and I worked together at Warner. Often people in business development [at music companies] come from one of two paths: f inancial or legal backgrounds. I was fortunate that Ole came from a more numbers- based, financial background, whereas mine was legal. He forced me out of my comfort zone. I wanted to look at the term sheet, and he told me, “You have to focus on the numbers. The numbers don’t lie.” Then we both moved to TikTok, and he [built] a great infrastructure of how the team operates, how we present budgets and how we work with senior management.

Related

How have you tailored your current role to your perspective and experience?

Ole was overseeing both recorded music and publishing, while I was more in day-to-day operations on the recorded-music side working with artists. So when I took on this new job, I said, “Why don’t we apply the best practices we have for artists to songwriters?” One thing that we’re particularly proud of is the songwriter feature we launched earlier this year [enabling songwriters to tag songs they’ve written in the music tab of their account]. The songwriters are really enjoying being able to step out from behind the curtain and get the acknowledgment that they deserve. We plan to roll that out more broadly.

TikTok increasingly has prioritized e-commerce with the TikTok Shop. How is your team working with artists there?

We are working with the e-commerce teams at the labels as well as our own. One thing we’re seeing is old vinyl sells. Even though people don’t have record players, they view these albums as collectibles. We also see great success when an artist does a livestream. We did one with Lizzo that was quite successful and one with the Jonas Brothers.

TikTok has hosted a number of intimate pop-up events recently for artists’ top fans. Ones with Miley Cyrus and Ed Sheeran come to mind immediately. This is an interesting move to me because you are a social media platform. You want to engage fans online. Why did you want to take people off their phones and get them outside with artists?

Music discovery starts on TikTok — discovery, promotion and fandom grows here, and we view it as a flywheel. After discovering a song, we then help to promote it with some of the campaigns that we do, then we tie that to the “Add to Music App” function so that you can listen on your streaming service. We’re see that what we do moves the needle on streaming, which then leads to charts, which then leads to increased fandom.

We thought that there would be a great opportunity to bring this to real life, to invite the fans that have the greatest engagement with an artist on TikTok to come see the artist in person, even if it does mean going off the platform for a bit. What I thought was beautiful about the Miley event at Chateau Marmont, was that the people there were so impassioned that they started posting so much about it. Even though I wasn’t there, they made me feel like I’d actually experienced it. Right now, we’re finding a way to create joyful intimate moments and creating them in a way that encourages fans to film and to bring them back onto TikTok.

Related

After a song goes viral on TikTok, it often ends up doing really well on streaming services. For a while, TikTok was building its own streaming service, TikTok Music. Why was it shut down last year?

It was just a decision of priorities. We were trying to grow it for quite some time, and the decision was made: “You know what? Out of all the things we’re doing, this is not succeeding at the level we want. Let’s focus on other areas.” It was an awesome service and it really tied in all the great parts of TikTok, but it was just a decision by management.

TikTok recently let go about 15 people from the U.S. and Latin American music teams, and layoffs are forthcoming in the United Kingdom. Some are interpreting this as a sign that the company is backing away from its partnerships with the music business.

As so many other big companies have recently done — Amazon announced a big round of layoffs, for instance — organizational changes are due to changes in structural needs. Companies can grow very quickly and then must reassess what’s best for them. There is definitely no change in the priority around artist services and artist relations. For us, it’s business as usual.

How are you reassuring the music industry that you remain committed to the partnerships and plans you already made?

We’re telling them it’s business as usual, and our valued industry partners remain the highest priority. We just want to focus more on the core priorities for artists and songwriters to help drive the value on the platform.

How is TikTok ensuring artists have safeguards against artificial intelligence-generated deepfakes?

We ask that users tag anything that’s AI-created. Aside from that, I don’t think the industry has a quick solution right now to identify those and take them down. If someone notifies us, our trust and safety team will take them down if needed. But it is a very interesting time right now.

Related

AI-generated songs have appeared on the TikTok and Billboard charts. Are you pursuing any policies that would bar AI music on your platform and charts?

It’s uncharted territory. Even with U.S. Copyright Office guidance that works must have sufficient human contribution to be protected, what does that mean? There’s such a wide span from a song being totally created by AI to one that’s created by a human with just one or two AI contributions. How do we decide when it’s such a gray zone? So I don’t think we’ve made a decision on that yet, and I don’t think a lot of the DSPs have either.

If AI-generated music starts performing well on TikTok, could it diminish the leverage rights holders have in negotiations with you?

I don’t think it would have any impact. We’re all aware that AI music is out there, and some exceptions have risen on the charts, but it would not at all impact the value that we see in our partners and how our deals with them are structured.

What are some best practices for artists seeking to gain an audience on TikTok?

The beauty of it is that any song has a chance to go viral. It just depends on how the billions of people on the platform react to the song. Oftentimes, I’m asked, “Do you have to be really leaned in?” It depends. A great example is Connie Francis. Her song “Pretty Little Baby” blew up this year. She wasn’t on the platform at the time. Eventually she did get on, which was great, but this music resonated [on its own].

Trending on Billboard

Mike Weiss and David Melhado like to tell the story of when they first met. It was 2019, and UnitedMasters artist NLE Choppa had just released “Shotta Flow,” which would eventually become a top 40 hit on the Billboard Hot 100, and Weiss, UM’s head of A&R, was interviewing Melhado for the company’s head of artist marketing position.

For the meeting, Melhado “had put together a web chart that had ‘artist’s vision’ at the center, and then webbed out A&R, PR, marketing, digital and brands that started from the basis of understanding who the artist is, what their objectives are, what their core audience is and then [how] everything has to tie back to that,” Weiss recalls in a listening room at UM’s Brooklyn offices. “That was my playbook, and I had not seen anybody else draw it in the exact same way.”

Related

Weiss, 34, and Melhado, 41, come from different backgrounds: Weiss is third-generation music business, after his father Barry and his grandfather Hy, and was effectively raised in the industry; Melhado got his start working for Jermaine Dupri‘s dad Michael Mauldin, building out the mid-2000s staple Scream Tour with artists like Bow Wow and Omarion. But they share a professional background in artist management — Weiss with Noah Cyrus and Labrinth; Melhado with Verse Simmonds and the producer Sak Pase — that has given them both a 360 worldview when it comes to artists’ careers, emphasizing building a brand and a catalog over chasing hits.

And at UnitedMasters — founded by veteran exec Steve Stoute, who runs the brand agency Translation, was an artist manager himself with Nas in the 1990s, and wrote the industry tome The Tanning of America in 2011 — the two are dedicated to doing just that. “We never made decisions based off, ‘This has to be a top 10 record, or we have to go to radio because we look to market share,’” Melhado says. “Because we’ve been consistent in our approach and made decisions that were best for the artists’ business, we’ve been able to see success and growth. We build brick by brick.”

UnitedMasters launched in 2017, in the midst of the distribution craze that exploded to serve the vast pipeline of artists that emerged in the DIY artistry world made possible by the streaming era and bedroom production tools. Many of those companies focused on scale and technology, mimicking the one-size-fits-all model developed by companies like TuneCore and Distrokid, which allowed anyone to upload and distribute an album for a set fee per year. Weiss and Melhado wanted to do something different.

“There hasn’t been a lot of [artist] development over the past 5-10 years,” Weiss says. “So we said, if everyone is going to be focused heavily on the A&R research teams, we’re going to find artists that we believe in and can develop. That was going to be our competitive edge.”

Related

Now, that focus is paying off, particularly after the two built a label business as the peak of a pyramid that encompasses DIY distribution at the base and a premium services tier in between, which has become the blueprint for the modern record company. Texas rapper BigXThaPlug‘s foray into country music was a massive success this year, yielding a top 5 Hot 100 single (“All The Way” feat. Bailey Zimmerman) and a top 10 Billboard 200 album; Floyymenor‘s “Gata Only” feat. Cris MJ won a Billboard Music Award for Top Latin Song of the Year in 2024; and partnerships with African super-producer Sarz and indie R&B singer and songwriter Brent Faiyaz have expanded their purview.

And now, as newly-minted co-heads of music at the company, Weiss and Melhado are leading the charge for all of it, staying ahead of the competition as the industry shifts towards their model. “It’s our job to always be changing and evolving,” says Weiss. “If the broader industry is doing what we set out to do, then that’s just validation that we’re on the right path.”

What was Steve Stoute doing at UnitedMasters that drew you to the company?

David Melhado: For me, it was new and he was bridging the gap between the brand world. When we came here it was very much a startup and the idea of being able to support artists at scale was attractive, but we knew it was going to be a challenge. He’s given us the space to fail fast and then pivot and try and take shots.

Mike Weiss: I was looking to be entrepreneurial and go somewhere where I could really help shape a business and touch everything. At that time, there were a number of key executives that were rolling out of the major systems and starting their own businesses that were having some early success. Making that bet on Steve that he was one of those people was a no brainer. But it also was the tech side of things I found really interesting as well, building a future of independence.

Related

Why did you want to build a label on top of the distribution business?

Melhado: We were doing these premium distribution deals, but labels were cherry picking all our acts. Lil Tecca, NLE Choppa, J.I. the Prince — as soon as they started to have a little bit of momentum the labels would come in because we didn’t have long term rights or a team that could really support them. So, that was the part of the argument to Steve: we have to change the way that we’re doing our deals. We have to really invest in the artists, and you’ve got to give us the ability to build the team. That was the turning point for us.

Weiss: We got to a point where we were saying, “We can identify talent and be successful with that talent, but what’s going to differentiate us from the majors if we don’t have the staff to really support that and take it to the next level?” A lot of companies in those early days of distribution were coming across that same problem — what’s the value of finding an amazing artist that’s going to develop into a superstar if you can’t be there when they’re a superstar? We said, Let’s build a label business and a team that can be competitive in terms of resources with the majors, but with the artist friendly deals of the distros. It was never a question of being the best distributor. It was, “Let’s be competitive with majors, and do it in a way that’s fair to artists.”

You guys had an advantage in being able to build a record label for this new era from scratch. How did you do it differently than what you would have seen at a traditional major?

Weiss: We said, what does development look like in the 2020s? Development is public, development is in the perspective of the fans. It’s similar in many ways to building a startup, which we have experience with now. You want to pivot quickly, you want to see what people are reacting to, you want to fail fast. You want to know what people are going to respond to and you want to start raw and authentic. And so we built A&R teams that could really get in the mix with artists. There are no longer gatekeepers that are going to press a button and all of a sudden your music is going to be everywhere and you’re going to be a breakout star. So we needed to put a team together that was wholly committed towards building something brick by brick from the ground up. And with that came the focus of constant progress, of being better today than we were yesterday, and making sure that whatever steps were taken were not in the pursuit of a hit record, but the pursuit of building an artist that has a foundation, a fan base, an audience that everything else can live within.

Related

One of your big success stories has been BigXThaPlug. How have you developed him through the years?

Melhado: When we first partnered with BigX in October 2021 he had 500 monthly listeners on Spotify. We took a really regional approach, working records in the clubs and trying to create an early groundswell, and did that same thing from a digital vantage point as well. We would release singles and then package them as an EP. Release more singles and then package it as an album. And we kept replicating that same process.

Weiss: The whole approach was consistency. The content mixed with the consistency just brought more and more eyeballs. You paired that with the localized approach to it and building a groundswell first that everything could rely on. For us, first week sales is not the barometer for anything. We’re not looking at the biggest moment and impact that we can possibly have week one that will jeopardize week 20. We’re focused on building an artist holistically and building that catalog.

Artists also need global reach. How did you guys approach that?

Weiss: The majors have companies in every territory. We’ve seen over the past two years that shift from a positive to a negative for the labels and a negative to a positive for us in that we have the ability to bring on whichever partner we want in whatever region. The team we would use in Germany for an Ekkstacy record would not be the same team that we should use for BigXThaPlug or FloyyMenor. So, we’re able to just bring in the independent partners within those specific regions that work directly for that specific artist. The approach has allowed us to have flexibility and bring in the right partners wherever it is internationally. Then as it came to finding international artists, the approach was similar — we just followed the talent. FloyyMenor, he was not a huge success at that point, but he was just buzzing in the scene. We saw a community being built around him and that real groundswell, which played into the way in which we already see and focus on developing acts.

Related

The culture of the business in Nashville is different than everywhere else. How did you guys move into the Nashville world for the BigXThaPlug album?

Weiss: The Red Sea parted for us on that. When we put out the “Texas” record, because it’s a country/hip-hop record already, we started hearing that Luke Combs and Morgan Wallen and Post Malone were fans. When he was still relatively unknown, the country community was actually the one community that was behind him. They welcomed him in with open arms. Dave and I went and sat with Charlie Handsome and talked about this idea of doing a country collaboration EP and he was down to give it a try. Then BigX posted an Instagram clip of “All The Way” with Bailey — people just went crazy. So the team went down to Nashville and met with every writer and producer. They all loved BigX because the artists loved BigX.

You share an office with Translation. How does that give you an advantage?

Melhado: Working with brands has been embedded in the DNA of UnitedMasters from the beginning. The early partnerships with the NBA and NBA 2K soundtrack; sync has been a part of the ways that we work with brands from day one. For an artist like BigX that has been very much a part of his story. One of the early brand deals that he got was creating the theme song for the XFL. I think it’s safe to say that we’re the only creative solutions company and creative agency that has a full blown music company and record label. That’s an important ingredient in the artist development story for us.

What does success look like for you guys?

Weiss: Success is when you see an artist that’s continuing to grow week over week, month over month, year over year. And the best way to do that is by building catalog rather than having peaks and spikes that are here today and gone tomorrow and then don’t really last the test of time in the digital era. Everyone talks nowadays about how catalog is the thing that is keeping the majors afloat. We don’t have a catalog to rely on and our goal is to build that.

Since January 2016, musicians who have struggled with the vagaries of compensation and regulation in their industry have been able to turn to one of their own for guidance, support and solidarity. That year, Richard James Burgess — who produced four top 20 U.K. hits for Spandau Ballet, managed bands, performed in one and oversaw business operations for Smithsonian Folkways Recordings — became president/ CEO of the American Association of Independent Music.

Next January, Burgess will step down after leading the organization through what Louis Posen, founder of indie label Hopeless Records, describes as “a period of unprecedented growth.” Under Burgess’ purview, Posen says, “A2IM has expanded its membership, created more opportunities for members and launched signature events like Indie Week and the Libera Awards.”

Trending on Billboard

During his 10 years at the helm of A2IM, Burgess also “built a highly engaged coalition of indie labels, large and small, and lobbied hard for them in Washington and across the music industry,” says Mark Jowett, co-founder and president of A&R at Nettwerk Music Group. “He fights each day for fairness and a level playing field,” adds Concord COO Victor Zaraya. “I will miss working with him.”

Burgess says that his stint leading A2IM has been animated primarily by a single principle: “Do what’s best for the creators. It’s the music business. But without the music, there is no business.”

Why did you decide it was time to move on from your role leading A2IM?

I made up my mind when I started that 10 years would be my limit. Mostly my career has fallen into 10-year chunks by accident. I tend to get to a point where I feel like I’m repeating myself. I like to do new things. Also, I think it’s good for the organization to have new leadership.

Over the decade that you’ve run A2IM, how has the definition of “independence” changed?

It still means the same thing it always did. People get confused about what corporate structures do around independence as opposed to what independence means. It means that you own your own copyrights or you have the freedom to do things the way you want to do them. Most artists, if they have the option, decide to go independent rather than with a major because they can steer the direction of their career more. Majors have extremely high goals for sales, and that usually takes a lot of compliance with certain kinds of criteria.

You don’t think that the major labels’ recent acquisitions of indies has changed the definition of independence?

The question is, how much does corporate ownership affect your ability to do the things you want to do? I don’t think it’s a healthy universe where all independents are channeled through the majors. But this is not a new thing. There was a peak of independence in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

There’s a long history of majors buying up indies, but is that happening at a different scale? Universal Music Group [UMG], for example, bought Downtown, which includes FUGA, which provides distribution for many indie labels.

That’s really upsetting a lot of independents. Having said that, there are options. Every time there’s consolidation, there’s a commensurate opening up of opportunities for new businesses and entrepreneurs.

What do you see as the biggest wins during your time running A2IM?

Coming in, I had several goals. One was to expand the organization, to make it more robust and as stable as possible. I think we’ve achieved that. Our revenues are much higher than they were. Indie Week is now a pretty established international conference. The other thing I’m really proud of is that we now are really established in advocacy. Nothing really happens in D.C. without us being involved. We get calls from congresspeople or their offices when there are any issues that might affect the sector, whereas we used to find out about it second- or third-hand or from the press that something was happening that could affect us.

How were you able to bolster the organization’s advocacy operations?

I [previously] worked at the Smithsonian, so I was in the D.C. scene for years, and I had a lot of helpful insight when I came to [A2IM]. The first couple of years, we didn’t have any lobbyists. We had to scrape the money together to afford our current lobbyists. They do an amazing job, and they don’t kill us financially. But frankly, we can spend 10 times as much money on lobbying and we still would not match what our opponents spend.

What are the priorities on the lobbying side?

We’re actually launching our own bills now. We have the HITS Act — that would let independent artists deduct up to $150,000 in music production expenses immediately. Another one is the American Music Fairness Act, which would make sure that artists could get paid from airplay. I’m really happy that songwriters get paid — this is not a zero-sum game. But radio stations are making money from selling ads against those records. Some of those ad dollars should go to the singers.

Another bill we think is really important is the Protect Working Musicians Act, which we launched with the Artists Rights Alliance. It would allow small- and medium-size enterprises — could be an artist, could be a group of labels or publishers or songwriters — to collectively negotiate against much larger [digital service providers] and AI [artificial intelligence] companies. These are among the largest companies that have ever existed. The leverage they have is completely disproportionate. You look at the statements people like Jack Dorsey and Elon Musk are making, which is that [intellectual property] should be considered fair use. When you look at the profits Meta forecast the other day, it’s hard to see why the source material they use to fuel this tool should be free. Nothing else is free. The coding is not free. The storage is not free.

Where are you and the RIAA aligned, and where do you differ?

We’re in constant communication with the RIAA, and we’re aligned on a lot. They’re part of the musicFIRST Coalition [which aims to “end the broken status quo that allows AM/FM to use any song ever recorded without paying its performers a dime”]. There are some differences, but we are 100% aligned on the idea that we need to preserve and increase the value of music copyrights.

In 2023, UMG CEO Lucian Grainge said that while conflict in the music industry was once primarily between indies and majors, today’s divide is “those committed to investing in artists and artist development versus those committed to gaming the system through quantity over quality.” Do you agree?

In 1999, the music industry reached its peak. We’re still down from that in terms of adjusted dollars. And that’s not accounting for the additional usage these days — anecdotally, I think there’s a lot more music consumed today than there was in 1999. Simply because of phones and [earbuds], accessibility has vastly increased. The reason we’re in this position is because we don’t control our pricing or distribution anymore. We gave that up in 1999 when we let Napster slip through our fingers. That can’t happen again. Obviously, we’re not in an exactly parallel situation with AI as we were with the transition to digital. But I do think it’s the music industry and musicians versus the tech platforms. Tech platforms want to lower the cost of what they call “content” and I call “music.” The musicians and the labels want to increase the value.

Are you taking any vacation after you officially step down?

I’m not good at vacation. A vacation to me is doing something different.

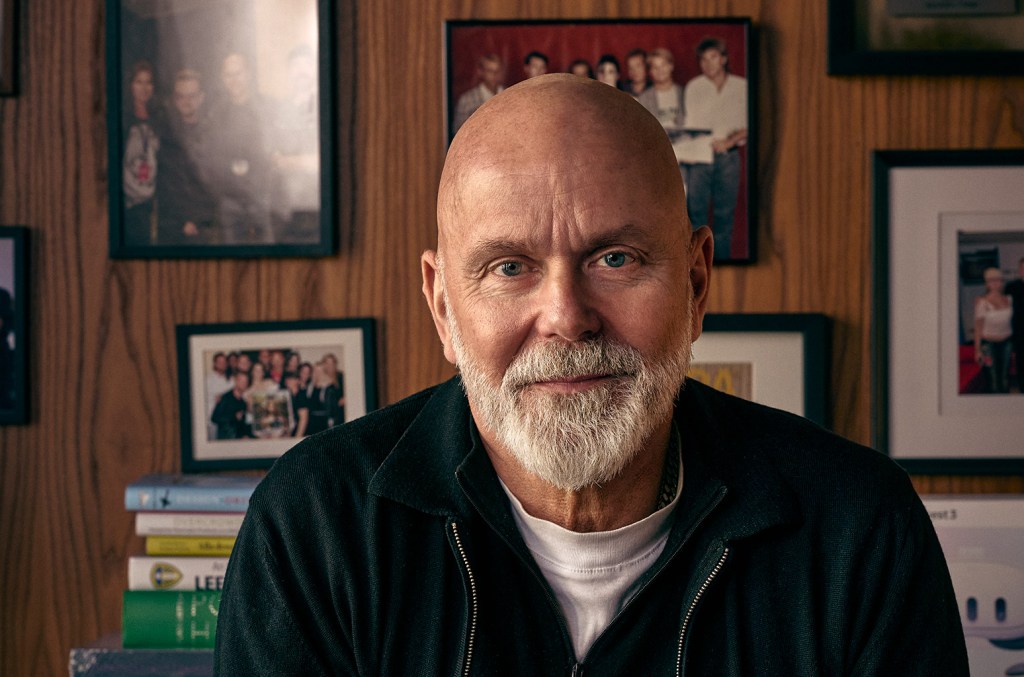

Lee Anderson‘s wife tells him he’s a hoarder, but he prefers to see himself as a Renaissance man of many interests — pop art, ’80s movie posters, ’90s TV action figures, baseball cards and a closet filled with more than 600 pairs of sneakers.

“I love having people over because I love showing off all the s— I have,” says Anderson, who is a year into his new role as president of Wasserman Music — a job that places him at the intersection of commerce and the biggest names in pop culture. He says his zeal for finding, signing and developing talented artists is no different from his passion for adding a rare or sought-after find to his various collections and is part of the skill set that makes him exceptional at his job.

Known for his unmistakable phone voice and large-frame glasses, the Bridgeport, Conn., native cut his teeth in live music working at Burlington, Vt., venues like Nectar’s and Metrodome. Eventually, he joined Paul Morris to work on the agency side of the business, which brought him to Paradigm and then Wasserman Music in 2021, where, in addition to overseeing Team Wass, he works with a client list that includes Skrillex, Zedd, Swedish House Mafia, Charlotte de Witte and Disclosure.

Trending on Billboard

How has your day-to-day changed now that you are president?

I have more responsibility for the business and everybody there, and I’m carving out extra time to make sure I allocate the right amount of time to each client [that I represent]. The net result is that I’m working significantly more hours. It’s looking at how to actualize and optimize all the opportunities that we have across our company with what’s already there. That doesn’t require a larger head count. It requires figuring out how to work better together and how we look at the whole business.

What’s a recent accomplishment under your leadership?

The hiring of Kevin Shivers, James Rubin and Cristina Baxter from WME. Having senior agents of their caliber, at the top of their game, join Wasserman was a milestone for our company, and I’m proud that we’ve been able to build a place that those three would want to join. Our culture of transparency played a role.

What kind of clients are you looking for?

We want to work with clients that we’re aligned with in terms of vision and approach. We’re known for discovering talent early and growing them into stars. But we try to be very thoughtful and honest and make sure that each agent who’s assigned a client has the bandwidth to give them what they deserve to get there. We really believe that everything starts with strategy — short and long term. It builds accountability for us as a business to do what we say we’re going to do. If we don’t, you should fire us.

Let’s talk about breaking your client, DJ-producer Yousuke Yukimatsu. He has landed some big U.S. bookings, including top billing at Portola Festival. How did you connect?

I saw him on the internet, and a manager that I have a relationship with called me and said, “Have you seen this?” I was like, “Yeah, I’ve been obsessed with it for like the last three days.” He said, “Look, we’re in touch with him, there’s a manager in place, and we’re talking about potentially working with her. Would you be interested?” I said, “Absolutely.” I got on the phone with them and laid out the way I would approach it. And I did what I said I was going to do.Wasserman Music President Lee Anderson on the Festival Headliner Shortage & Why Fyre Fest Isn’t an Anomaly

What’s your strategy for him?

Generally, when you’re coming in, there are metrics of ticket sales or streams or social media engagement. But he’s unique. This wasn’t a producer with a bunch of his own records. He’s very much a Laurent Garnier-style selector and very respected DJ and technician. There was a huge swell of excitement around him. Danny Bell at Portola Festival saw that right away. Huston Powell with C3 saw that right away. We began to put some headline shows up, selling out 3,000 and 5,000 tickets instantly. He had goals, and I understood the aesthetic and types of events and artists he wanted to play around and the types of rooms that he wanted to be in. And we were able to put that plan together.

Are festivals still a good outlet for breaking artists?

Yes, but it has to make sense. There were times when we’d envision our artist playing in front of 15,000 people, and they’d actually be performing for closer to 400 because they’re on at 2 o’clock. So now I ask a number of questions: Is this going to be an impactful moment? Who else is playing at that time? I usually start with that before I even start with the fee. I don’t think I’ve ever had a deal die over the money.

Is there a headliner shortage in the festival space?

It’s hard to get a headliner these days, and that has hurt the festival ecosystem to a degree. I don’t want one client playing 40 festivals in a summer. I want my clients playing the right moments, with different cultural ecosystems that appeal to different audiences.

What makes a good festival talent buyer?

The best talent buyers are the ones that are calling me and chasing me about an act that I haven’t even pitched. Buyers who like to put cool packages together.

Do you want your agents pitching all the big festival buyers?

If an agent sends a list of hundreds of acts to a festival buyer, they’re not doing their job. If an agent’s doing a good job, they should have a plan and targets for their clients. They should be inviting buyers to a show or sending music or doing all the things it takes to get those bookings.

Billy McFarland flamed out trying to revive Fyre Festival. Could another disastrous event like that happen again?

As long as there are ambitious, naive people all over the world who do not recognize their blind spots or realize they’re capable of failure, there will be festivals that crash and burn. I just don’t want to work at the agency that’s got half the lineup on the next one that goes down. It’s very important for agencies to be diligent about what they’re looking at in terms of live opportunities for their clients — and not just look at an offer with a big guaranteed number. Fyre is not the only time we’ve seen things like that.

Tell me about some of the things you collect.

I love Danny Clinch photography. My two favorite artists of all time are Jay-Z and Phish, and I have Clinch prints of both. And for my birthday like eight years ago, Clinch printed and framed a photo that he had taken of me and Skrillex together at Bonnaroo and signed it for me. That is one of my most prized possessions. I collect a lot of toys and pop culture items from the ’80s and ’90s like Miami Vice action figures still in the packaging or like Cheech and Chong or Jay and Silent Bob. I have all the McDonald’s cups from the Dream Team, and I collect sports cards and baseball cards. I’m into sneakers and have over 600 pairs, mostly Nikes, as well as the old Charles Barkley and Deion Sanders sneakers and stuff that I probably will never wear. But I have to have them because I had them when I was in sixth grade or something.

What’s the most you’ve spent on an item for your collection?

I spent seven years collecting all of the original Hasbro World Wrestling Federation action figures from the late ’80s and ’90s. Some of those in the newer, limited series are hard to get, and I paid between like $300 and $400 per figure.

In 2022, Pophouse Entertainment premiered ABBA Voyage in London, a virtual concert in which avatars of the Swedish powerpop foursome as they appeared in 1979 — one of them Pophouse co-founder Björn Ulvaeus — performed their biggest hits in ABBA Arena, a custom-built venue at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park that seats 3,000.

More than 40 years after ABBA’s initial success and the subsequent popularity of the Mamma Mia! musicals and movies, fans have purchased more than 3.3 million tickets to over 1,000 ABBA Voyage shows, according to Pophouse, which cost approximately $185 million to mount. Now, armed with $1.3 billion from its first round of private equity fundraising and the backing of Swedish investment giant EQT, Pophouse CEO Per Sundin is eager to replicate the franchise’s success.

Sitting in front of photos of Michael Jackson, Destiny’s Child, Lana del Rey, Billie Eilish, Barry Gibb and other artists Sundin worked with during the decades he spent as Sony and later Universal Music Group’s top executive in the Nordics, he sees ABBA Voyage as a template to attract the devoted fan bases of certain other acts. KISS, which completed its End of the Road tour in 2023 and whose catalog Pophouse acquired the following year, will be the next act to get the avatar treatment. Another possible candidate is Cyndi Lauper, whose farewell tour ends in August and whose catalog Pophouse owns. The company’s portfolio also includes the catalogs of two of Sweden’s most famous electronic music artists, Swedish House Mafia and the late DJ Avicii, for whom the company recently said it will release new music.

Trending on Billboard

Speaking at the New York offices of law firm Morrison Foerster, Sundin says Pophouse didn’t cut any corners in creating ABBA Voyage — even footing a “shocking” Dolce & Gabanna clothing bill, Sundin says, for the avatars’ costumes. (“They should have sponsored us, it was so expensive,” he jokes.)

Sundin says that after KISS vocalist-guitarist Paul Stanley saw ABBA Voyage, he asked to meet the band members backstage. Pophouse, he adds, is dedicated to producing the same realism for the blood-spitting, fire-breathing “Black Diamond” boys.

Geopolitical uncertainty and tariffs have not directly affected music assets. Did that motivate investors who participated in this latest funding round?

I don’t want to comment on what’s going on in the world today because I can’t guess where anything is going. But music is totally uncorrelated to inflation or interest rates, and that is a key message for people who invest from the financial world. When we said to investors, “This is a yield business because you have royalties coming in every quarter,” the financial support for music is fantastic. Even though you have tough times, maybe you don’t go out to restaurants or do big trips, but you will never cancel your Spotify, YouTube or Apple account.

You may not cancel your Spotify account, but you do buy fewer Broadway tickets. How are you changing your forecasts for the ABBA virtual show or other live- entertainment projects?

You have to value in assumptions and calculations for every venture, but we’re not going to do nothing for four years. The world we’re living in, it’s always SNAFU [an acronym for “situation’s normal: all fucked up”]. There is also opportunity. There is so much need for entertainment. ABBA Voyage is the next generation of music concerts. It’s on seven days a week, and it’s almost always sold out. I’ve been 16 times, and I’m emotionally connected every time. That’s how contagious this show is. Of the 50 biggest artists in the world still alive, I would say that 40 have been there to see it.

Given the show’s popularity with big stars, how’s your pipeline for acquisitions?

Really good. The press release about how much money we raised helped. We hope to announce at least one catalog we’re buying by summer. But we don’t just want to buy it and put it on the shelf. We create a road map for five to 10 years, and then we execute that road map. From the beginning, we told our investors that we want to buy eight to 10 catalogs. We have four. That leaves six to buy. The record companies have thousands of catalogs.

In the United States, ABBA Arena would be comparable to Sphere in Las Vegas. Will the KISS virtual show take place there?

No. The Sphere is a fantastic building, a fantastic venue, but for the type of avatar concert we are planning with KISS — which is something else — we are looking at more intimate sites. I’ve been to the Sphere four times [to see U2 live, a video replay of a U2 show, Anyma and the Eagles]. The first time I saw U2 at Sphere, the visuals were amazing, but I didn’t feel emotionally connected. Bono is a preacher. He has something to say to the world, and I didn’t find he was in the right element. I saw U2 virtual [a recording of a prior Sphere performance], and Bono was more of a preacher there. With U2 [both times], I asked people, “Did you go for U2 or did you go for the Sphere?” Two-thirds said they went there for the Sphere.

How will you give KISS fans something new for the virtual show?

Every catalog we buy will not be an avatar show. ABBA was only active for eight to nine years. KISS toured for 40. Kiss is more male-biased. ABBA is more female-biased. But they both have fans of all ages. That’s why their brands are so valuable. If you’re a KISS fan, you’re a fan for life.

Pophouse also owns Avicii’s catalog, another artist with hyper-engaged fans who are very sensitive to coverage and monetization of that catalog, given his suicide at the age of 28 in 2018. Would Pophouse buy another catalog that comes with a significant risk of offending fans?

There is so much data available to look at before we buy catalogs today. We also do brand and narrative due diligence. KISS has superfans. Taylor Swift has superfans. The same goes with Avicii. On Spotify, 2% of listeners of a catalog stand for 80% of a catalog’s streams in an average month or year. In some cases, we have found 5% [of listeners] stand for 50% of streams. If I can increase an act’s superfans from 5% to 6%, the total streams will go up 10%, meaning the value of the catalog will go up 10%.

So back to your question about sensitivity: We take this very seriously. With KISS, there are fans that have been fans for 50 years. We did deep research and collected 10 people into a superfan panel and invited them to Vegas [in mid-March]. In workshops, we asked them what they would expect, what they liked and didn’t like because we respect them. That doesn’t mean we will do everything they say. We will adapt their feedback for the next 50 years.

We’re going to do a superfan panel with Avicii, too. His parents are very close to me personally since I signed Avicii in 2010. I am probably the person who is saying, “Do as little as possible.” There are a lot of things Avicii never released, and we are doing Avicii Forever, a collection of his best songs — and one new song.

What’s a challenge you encountered in your career, and how did you overcome it?

The first decade of the century was a true roller coaster for me, but also for everyone in the music industry. It started with the best year ever selling CDs, then came Napster, LimeWire and, eventually, Pirate Bay. Sweden was the most pirated country in the world, and I had to restructure Sony Music Nordic. Then came the merger between Sony Music and BMG, and I moved to Universal Music Nordic. I had to let more than 300 people go, and the music market in Sweden decreased 50%. We tried everything to overcome the shrinking market: ringtones, iTunes and many more. Nothing compensated. When I joined Universal in April 2008, UM Sweden had the lowest digital revenue based on micro [gross domestic product]. Spotify was launched that October, and I decided to go all-in and sign as many new and established artists as possible: Avicii, Alesso, Tove Lo and many more. In 2013, Universal Music Sweden had the highest digital revenue on micro GDP in the [entirety] of Universal Music.

What are you most proud of from your career?

Every artist you sign to a label you feel in some way connected to them. I don’t think they always feel connected to you, but to sign an artist or band is such an important decision [for everyone involved]. Even though I’ve left Sony and Universal, I continue to follow the careers of the artists I signed. It’s emotional. It’s about creating an entertainment brand or artist who can live on their creativity. It’s fantastic.

Earlier this year, Univision Networks Group president Ignacio Meyer‘s role was expanded to include oversight of the Hispanic media giant’s portfolio of 35 owned-and-operated radio stations, nearly 300 affiliates, its Uforia streaming app, live-events business and networks group. The promotion empowered Meyer to fully execute his longheld vision for a streaming-era business strategy. In the wake of Univision’s $4.8 billion 2022 merger with Televisa, his division would operate as part of a global, vertically integrated multimedia company where content created by different units can move freely between countries and platforms, including VIX, the company’s growing streaming enterprise.

That content includes music, and Meyer says he’s focused on fortifying its strength as one of the “pillars”— in addition to drama and sports — of the TelevisaUnivision brand.

For the company’s consumers, “Calling music a passion point is an understatement,” the dapper, Madrid-born executive says. As a result, “The entire company is behind it.”

Meyer, who is known for booking music artists himself on Univision shows and sending personal thank-you notes afterward, is well-loved by the industry, and his office is decked out with signed gold records, awards and other memorabilia. His walls will inevitably become more crowded, given his plans to return Univision to the music business. In the early 2000s, Univision Music Group operated as a label, which was sold to Universal in 2008 (before Meyer joined the company). And in 2016, Univision’s Fusion Media Group division signed a multiyear, multiplatform deal with former Calle 13 member Residente, which is no longer active.

Meyer spoke to Billboard about those plans, as well as his strategy for harnessing the power of music to Univision’s advantage.

How has your job changed since your promotion?

The big difference is we’ve become a platform-agnostic, content- and audience-first company. We’re fortunate enough that, over the years, our ownership has invested in all the platforms. We have TV stations, local and national networks, radio stations, top digital destinations — whether it’s web- or social media-based — and now we have a dedicated streaming platform, VIX. This year, for the first time, we deployed a global content investment strategy and looked at every content investment for profitability and distribution purposes, regardless of platform or country. That’s new and different because we realize that the strategy of having the consumer at the forefront is not about pulling them to a particular platform. It’s about making sure we are everywhere they are and that they can flow freely.

How does music play into that?

Music is a passion point for U.S. Hispanics. We feel strongly that Latin music is mainstream today, and we need to follow that mainstream consumer everywhere they are. So we’ve made structural changes to allow music to travel more seamlessly throughout our ecosystem.

If you look at the history of Univision, there are isolated pockets of success with music. What was missing is the connective tissue. We’re eliminating the barriers between calling something a “radio product” or an “audio product” or a “national” product or a “local” product. It’s intellectual property. It’s music, it’s a song, it’s a brand, it’s an artist.

Can you give me an example?

This year, we treated Premio Lo Nuestro [an annual awards ceremony that recognizes achievements in Latin music] as a platform-agnostic event. It was simulcast on streaming and we had events [tied to] fashion and social with some brands. We decided to light up YouTube and social media before we aired the show, so we did our version of off-air awards and the pretelecast on digital networks. And it was all supported by audio-first talent that represented different genres. For example, we featured talent from our [Mexican musicfocused] radio show, El Bueno, la Mala y el Feo. Just as we lean into our [TV] consumer brands, we’re going to lean into our radio show brands and elevate those shows. And we’re crosspollinating. TV host Alejandra Espinoza, for example, is now also part of our Los Angeles morning radio show.

Awards show viewership in general has declined. How do you make yours profitable?

We found a way to make money because we studied the ecosystem. It’s not just a TV show. We’re communicating, we’re editorializing, we’re telling a story, and we’re using music to do so — across all of our platforms. It creates more inventory for brands to get more deeply involved. Ratings define and validate the commercial side of ad sales, but it’s not the only measure of success. Total impressions, total reach, influence — that is success.

How else are you expanding Univision’s music presence?

We are looking at entering the music business again through strategic alliances. That is new. I don’t have the format a hundred percent. I don’t know if it’s a record label, but by virtue of this vertical, content-first approach, I am going to be getting back in touch with the industry. We want to be a more regular part of the music ecosystem. It could be a strategic alliance with a particular artist, a distribution deal with an artist, a management company, a publishing company or the distribution and promotion of music. I will generate content with you. I will generate social currency. We will make money by participating in a revenue share or license fee of the actual revenue streams we generate.

Some companies are not as convinced about the viability of music as a revenue driver.

We are. We demonstrate it day in and day out with our properties, and we know we could do more with it. So that’s where the investment comes in. Could we have done it as a company 10 years ago? I think the answer is no. Structurally, we probably weren’t set up for it. The power of music is it travels with no borders. Now we have the platforms. You can consume via audio, video, streaming.

Does Univision have any music-driven shows in the pipeline?

There will be announcements made, likely at the upfronts [in May]. But our approach is holistic. For example, you’re going to see a lot more radio shows like El Flow and El Bueno, la Mala y el Feo — which are also podcasts — on TV or on VIX. We are no longer taking a TV-centric approach to business. We will have music properties, but it’s not going be a one-show-fixes-all. Scripted is still a huge vehicle for music, for example. And we have a publishing business with over 100,000 copyrights here that I’m also managing.

What really drives fans to tune in to music-adjacent programming?

Storytelling and pop culture. Music has become a synonym for lifestyle. And it has a lot to do with social media and the way artists interact with their fans. Permanence in any kind of show all year is the most important. Also, there is a lot more being done in scripted than we are getting credit for as a music industry. There are so many storylines, documentaries, entertainment shows that are in and around music. How do we get people to engage? The most successful reality shows on television today have more hours of digital content than they do of [regularly scheduled] linear content. Because there are multiple platforms, they are “always on.” The Latin market is diverse, and we are more than a media company. We are a cultural representation of the Latins who live in the U.S. and of the way we live in the U.S.

This story appears in the April 19, 2025, issue of Billboard.

Days after Kathryn Frazier lost her Altadena home in January’s Los Angeles wildfires, she returned to survey what was left. “On my property, I had four little sheds and [one] was a healing room. There was a 300-pound citrine crystal in the middle and a Reiki table,” she says. “When I drove up there, the entire street was gone. Everything on my property was gone — except for that healing shed.”

Frazier has worn many music industry hats across her 30-plus year career. In 1996, she founded the publicity firm Biz 3, which has staffers working remotely in several states. Its roster of 200-plus clients, who are primarily in the music business, includes The Weeknd, Lil Yachty, Chappell Roan and Victoria Monét, as well as known figures in film, TV, sports and comedy. In 2011, Frazier co-founded independent label OWSLA with Skrillex and others. And in 2018, she became an International Coaching Federation-designated Professional Certified Coach, enabling her to guide clients on professional and, if they choose, personal matters. She also teaches at the University of California, Los Angeles, is a certified reiki master and authored an upcoming book about co-parenting.

“All of the tools, routines and perspective that I’ve been cultivating for the last 30 years literally felt like I had the world’s biggest, best insurance policy for emotional and mental health when something devastating or tragic happens,” Frazier says, reflecting on the fires. “And it saved me.”

Trending on Billboard

Frazier used those tools to keep working despite the personal devastation she had suffered. The fires had upended clients’ plans and her expertise was needed to, for example, help deal with the cancellation of The Weeknd’s Los Angeles show and postponement of his sixth album, Hurry Up Tomorrow.

“A lot of times, you have to keep going because it’s your livelihood,” she says. “And of course all my camps were so loving and like, ‘Please take what you need.’ But there was a certain drive in me [to be] of service to others, whether it’s in a philanthropic way or [the way] I’ve dedicated myself to helping [their] art. It does take you out of yourself in a healthy way. It’s like walking on a tightrope, but because of all the years I’ve been doing this, my tightrope is a wider path, almost like a bridge.”

How have you coped these last few months?

I’ve done a lot of surrendering, a lot of acceptance. For the first month, did I [use] all my tools? No, I was waking up every day in fight-or-flight [mode], just trying to emotionally process. Grieve. Get my family set up so we have somewhere to live. You’re really, truly kind of starting over. And then also taking care of business. The day I woke up from the fires, I had the launch of The Weeknd’s album campaign with a magazine cover. And I just didn’t stop. It was a really big test of how I operate or show up when shit hits the fan. And all the tools absolutely served me.

Why did coaching feel like a necessary next step in your career?

I was becoming very disenchanted with the industry and felt really empty. Then I started to see a lot of people suffer — and not even people I work with. A lot of addiction, a lot of mental health stuff, a lot of just being worn. Resentment, anxiety, depression, all of it. I had a bigger calling, and why not be able to help people [spread their] art? Whether it’s me doing their press or marketing or getting someone into a better headspace. That’s why labels and managers want me to see their artists. And I always encourage people to have [their artists] see me when they’re just beginning so that they don’t go off the rails. Versus bringing me someone who’s totally at the bottom and struggling and now has to cancel a hundred-date tour or something. It’s preventative medicine.

How big is your coaching client list?

I have a waitlist that I operate from. But because my coaching clients travel so much, I can always get people on the list. I coach a lot of large artists. I coach [senior] executives. And I also coach people who have nothing to do with any of that. The one thing I find is it doesn’t matter who they are or what their position is in life. The inner self-talk tends to be the same. The obstacles tend to be the same.

Since you’ve started coaching, have you seen a shift in how the music industry supports the wellbeing and mental health of its artists and executives?

I still constantly hear of people or see people being pushed and propped up, and I don’t think the music industry is negligent. It’s more that people don’t know where to go or they don’t have the resources. They don’t know what to do with a drug-addicted client. Like, “Who do I call? Do you know any sober coaches?” Often, it’s not knowing how to have the hard conversations when you see someone struggling. Many times over the years, I have gone up to artists — and again, a lot of them are not people I rep — when I can tell they’re struggling, in particular with addiction, or when I hear that they’re canceling a lot of tours and shows, I’ll be like, “Sweetie, tell me what’s happening. I can see you’re struggling.” And almost every time, they literally fall into my arms. They want to talk. They want help.

How are you working to broaden a community that can help?

It’s what I’m teaching. My course at UCLA is about the music industry, and it has become really popular. The kids call it “the manifestation class.” It’s half “What do you need to do to move forward in music?” Almost all of them are musicians, as well as people who want to be in the industry working. It’s also [half] “How do you navigate your own inner voice?” The negative self-talk, the imposter syndrome, the scarcity mindset, the indecision, compare-and-despair. And then, “How do you navigate and handle the outer voice?” The media voice, the public voice.

Your partner Dana Meyerson represents Chappell Roan. How did you feel about Chappell’s Grammys speech regarding the industry supporting artists’ mental and physical health?

I got tears in my eyes immediately and I had a resounding “Fuck yes” come through me. Because we do need to take care of the people who are actually creating the business of this entire business. And I so applaud anyone with a platform using it in service of helping other humans, especially with their mental and emotional health. It made me very proud that [Chappell is] a part of Biz 3. It made me so proud that I have a business partner in Dana that can recognize amazing talent and also have artists that say something on our roster. Dana has truly done the come-up in this industry and now is the reigning queen of PR, in my opinion. She finds the best, most amazing artists and builds them up to massive success.

Have you thought about helping other music companies establish career and wellness coaching?

That would be my dream. The main thing that would require is a budget. If even the smallest amount of earnings could go into hiring a couple of [personal and professional] coaches that could help your staff and your artists for 45 to 50 minutes every other week, you would have such a different company culture. When I quote unquote retire, it’ll just mean I’m fully coaching, writing books and teaching. And maybe that’s me trying to spearhead coaching divisions at companies.

How has the role of a publicist expanded over the years?

All the big press stuff is still there, but there’s also a lot of paid media. That’s been the most disheartening part for me. I’m afraid for it to go too far because then we stop having editorial, we stop having curatorial voices, we stop having people who are truly discovering what is amazing out there versus what got paid for. So I’m really hoping that doesn’t usurp the true editorial and curatorial.

We’re also seeing an uptick in influencer-based media. How does that affect your approach to publicity?

It changed the scope. There are more conversations with YouTubers that review or do music or certain shows [on] TikTok. I am 1,000% a glass-half-full person — I’m a recovered cynic. I’m like, “All right, what new opportunities are there for us?” There might be some magazines shuttering, but what other interesting way can you get good art out to the masses? Like, I’m not going down with the ship. Let’s keep it moving.

After a difficult 2024 in which a number of major festivals closed their doors for good, Coachella sales were down and Burning Man didn’t sell out, WME global head of festivals Josh Kurfirst says, “Protecting the health of the festival business has become central to everything we do.”

“It’s no longer an incoming call business,” says Kurfirst, the son of Gary Kurfirst, former manager of Talking Heads, the Ramones, Blondie, The B-52s, Jane’s Addiction and Garbage. Early on, the job of most festival agents, Kurfirst explains, was to field offers from festival talent buyers for artists on the WME roster, negotiate where the artist’s name would appear on the festival poster and review daily ticket sales drops. But as the market matured and evolved, he instructed his staff to get more aggressive about pitching WME acts to prospective buyers and finding opportunities for them to bookend tours and live shows around festival appearances.

“Everything is strategic,” he says. “It’s not, ‘Let’s just throw 300 bands on this festival because it’s easy.’ We don’t do things easy.”

Trending on Billboard

Despite the cancellations of such once-popular festival brands as Faster Horses, Sick New World, Something in the Water and Alter Ego, Kurfirst and his team have plenty of success stories to tell. This year, his team helped land Zach Bryan his first headliner date atop the Stagecoach festival, secure newcomer Benson Boone a top slot on the Coachella lineup, book The Killers as headliners for Lollapalooza and secure headliner slots for Luke Combs, Olivia Rodrigo, Hozier and Queens of the Stone Age at Bonnaroo.

2024 was a tough year for festival sales. What happened?

First, it’s important to acknowledge that the festival market has significantly increased in size in the last decade. When I first started, there was a smaller group of giant festivals that had most of the market share. Since then, we’ve seen the emergence of a middle tier, a lower tier, a genre-specific tier and a lifestyle branch of festivals. And those have taken some market share away from the crossover contemporaries — the Coachellas, the Lollapaloozas and the Bonnaroos of the world. There’s really something out there for everyone now as long as you’re willing to travel. Look at Morgan Wallen’s new Sand in My Boots festival on the same site as the old Hangout Festival, which had been a steady market for years. Some years it sold out. Some years, it came close, but it never blew out on the on-sale. All of a sudden, Wallen comes in and launches his own festival on the site and it sells out instantly.

Atop a bowl of all-access festival and tour laminates, Kurfirst displays a copy of photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s Music in the ’80s book, open to a shot of the Talking Heads, whom his father, Gary, managed.

DeSean McClinton-Holland

What did Wallen do differently from Hangout Festival?

Instead of trying to create an event that appealed to as many people as possible, Wallen created an event that overdelivered to his fan base. He rebranded the festival under his own name and booked more than a dozen similar artists that he believes will connect with his fans. [This year’s lineup includes Bailey Zimmerman, Post Malone, Wiz Khalifa and The War on Drugs.] If you’re a fan of Morgan Wallen, then you won’t want to miss out on the Sand in My Boots festival. And, by the way, if you live in the Southeast, it might be your only chance to see him play this year.

How are overall festival sales so far, compared with 2024?

Last year was interesting. It wasn’t just straight down. It was choppy water. This year is still early. Most of the festivals just announced their lineups, and from what I’m hearing, it’s been positive. The overall market feels like a bounce-back year, and a lot of that has to do with the headliners. We’ve had a solid crop emerge — Olivia Rodrigo and Hozier, for instance. To a young artist like Olivia, these festivals mean something. It’s a notch on her belt and a way to do something in her career that she hadn’t done before.

Kurfirst’s mother, Phyllis, created this framed collage that, in addition to ticket stubs from concerts that Gary promoted, depicts (clockwise from top) Phyllis and her pet huskies; Gary and Phyllis at his parents’ house; and at their alma mater, Forest Hills High School.

DeSean McClinton-Holland

How do you judge success at WME?

It’s not based on quantity or how many festival slots WME artists are on. We’re very selective. We’re building careers. And we want to make sure when it’s our clients, they’re in the right cycle in terms of their music cycle. Typically, that means the artist has new music ready for the fans to discover and plans for either touring or other dates that they want to build momentum behind. They’re going to play the right slot, they’re going to get the right billing, they’re going to get the right money. That’s the time to play the festival. If any of those things are off, we’ll just do our own thing — meaning, we’ll work with a promoter, headline our own tour and continue building their hard-ticket business, which is incredibly important for all our artists.

Are festivals still a healthy launching pad for an artist’s career?

They are a good developing mechanism for new artists, but again, it has to be the right moment. I don’t know that it would make sense to just throw a new artist that doesn’t have any music out on a festival [stage] at 12:30 p.m. when the doors open. That’s a wasted booking. It would be better for that artist to be in cycle, have music out, have some press, garner some reviews ahead of time, so people actually have the ability to do their research and [want to] show up in front of their stage.

Pillows commemorating Madison Square Garden shows by artist clients whom Kurfirst represents in addition to overseeing WME’s festival division.

DeSean McClinton-Holland

The festival market has had an uptick in cancellations in recent years. In that environment, how does WME maintain a positive relationship with promoters?

We look at the promoters as our partners. They’re not on the other side of the table; they’re on the same side of the table. We want them to succeed, and we have their backs. In return, they have our backs, too.

What does it mean to have each other’s backs?

With festivals, artists sometimes have to cancel. Sometimes they get sick, they break a leg, the album gets pushed. Sometimes it’s our clients. Sometimes it’s clients from other agencies. What we do in those situations is we don’t bury our heads in the sand. If it’s a Saturday at 3 p.m. or 7 p.m. or 7 a.m., we’re there for our buyers to fill that slot that suddenly becomes open. And because we book things through one point of contact, the buyer only has to contact one person at WME. That’s his partner, his festival agent, and that festival agent then canvasses the entire roster and can come back with real-time avails within hours.

Kurfirst with his four kids, from left: Landon, 17; Ariela, 11; Eden, 11; and Lucas, 21.

Courtesy of Josh Kurfirst

Are you bullish on the long-term prospects of the festival business?

It’s a very Darwinian environment out there and the strong will survive. There are times where we have to have tough conversations with our promoter partners and come to a fair settlement where our clients feel good, but where we don’t put the promoter out of business. Because that doesn’t help anyone. Make no mistake: When we do a deal, our clients are entitled to 100% of the money if a festival cancels due to poor sales. There are some reasons why a promoter can cancel, like a pandemic. But in most cases, if a festival is canceled, it’s due to poor sales or some sort of promoter breach, and our clients are entitled to 100% of the money. It’s our job to come up with a fair settlement where the client feels good and the promoter is able to get back up on their feet.

What’s one of the most important lessons your father taught you?

He taught me that loving what you do is the single most important decision we make as adults. If you don’t, you can’t bring passion to the job every day. He also taught me about not trying to be someone else. Don’t just go with the trend. He equated that in how he chose the artists he wanted to work with, whether it be the Talking Heads, the Ramones, The B-52s, the Eurythmics, Jane’s Addiction and Mountain. These bands weren’t genre-defining — they invented their genres.

This story appears in the March 8, 2025, issue of Billboard.

In the ever-evolving world of music asset trading, Influence Media Partners early on broke away from the initial frenzy over evergreen rock music classics to pursue a riskier strategy: acquiring contemporary music catalogs, including hip-hop. One of its biggest deals was the 2022 acquisition of Future’s publishing catalog, which consists of 612 songs composed from 2004 to 2020.

Last year, Influence Media, which is backed by BlackRock and Warner Music Group (WMG), expanded its operations with the founding of SLANG, a label and music publishing operation. While the music company has signed publishing deals and separate joint ventures with Future and DJ Khaled that allows them to sign songwriters to publishing deals, its label is betting on such developing acts as hip-hop artists Camper, RX YP and TruththeBull — a sector of the business that usually does not attract institutional investors.

Rene McLean founded Influence Media in 2019 with his wife and business partner, Lylette Pizarro McLean, a former music industry marketing executive, and Lynn Hazan, a former CFO for Epic and RED. He grew up in New York just before hip-hop music and culture were becoming mainstream in the early 1990s. “What do you do when you’re 18 in New York City?” he says. “You start clubbing. I got drawn into nightlife and music, and I loved hip-hop and did break dancing and graffiti and all that stuff.” Even though he was the son of jazz musician Rene McLean Sr. and the grandson of renowned jazz saxophonist-composer Jackie McLean, “I didn’t want to be a musician or in the music business,” he recalls. “But then something went off in my head.”

Trending on Billboard

“I like to keep meaningful books and collectibles I’ve picked up throughout my career to remember where I come from.”

Carl Chisolm

After landing a promotion position at Virgin Records, followed by similar jobs at RCA — where he worked with Mobb Deep and Wu-Tang Clan — and Elektra, McLean formed Mixshow Marketing and Promotion company The RPM Group before founding Influence Media.

What led you to found Influence Media?

At that point in time, I had created a conference, a trade magazine, and, through the conference, we were doing a lot of brand work. That’s when Lylette Pizarro entered my life. We had gotten corporate clients to sponsor the conference, so we went out and created our own boutique agency, which wound up having a bunch of Fortune 500 clients like PepsiCo, LVMH and Verizon. We did everything from sponsorship to endorsement deals to strategy work, and that led us to think if we’re going to really get back into the nuts and bolts of the music business, the only way to really be impactful was to create Influence Media. By then, streaming had come on, and we saw the future. So we raised money and acquired three catalogs, which we then sold to Tempo.

After selling those catalogs, you got $750 million in funding from BlackRock and WMG and bought more catalogs — Future, Blake Shelton and Enrique Iglesias. Why start SLANG?

Lylette and I felt that, outside of acquiring and investing in these catalogs, there was an opportunity to build a label and a publishing company. I’ve always looked for the white space. We’re not just finance folks; we come from the music business.

Is WMG a partner in the label? Are you using them for distribution and publishing administration?

Yes, SLANG is a part of Influence and Warner is one of our strategic partners in Influence.

“My son painted these art pieces,” McLean says. “I love the color that they add to the office.”

Carl Chisolm

Who is doing the A&R and signing the artists to the label?

I’ve done all the signings to date, but we’re going to bring in a head of A&R. We now have a staff of about eight. But it’s been very boutique in the way I’ve been looking at these acts. We really want to develop these acts properly and break them solidly. And it seems like it’s really going in the right direction.

In looking at your roster, the bigger names are Will Smith and The Underachievers.

Will Smith is a distribution deal. But we’re highly involved in all the marketing and everything else. We work closely with Will’s camp. They’ve been great partners. And we just had our first No. 1 gospel record with him. So that’s wonderful right there.

I would classify the rest of your roster as developing artists, like Camper and RX YP.

Camper is incredible. He is a Grammy-nominated R&B producer, and he’s done a lot of things with H.E.R., Daniel Caesar and Coco Jones. RX YP is a rapper from Atlanta, very street. We also have, like you mentioned earlier, The Underachievers, who were originally signed to RPM and we picked them back up. They have a project coming out soon. They’re doing something with the clothing designer Kid Super. We’ve got TruththeBull, which is a true artist development story in the making. His debut mixtape is coming out in April, and his most recent single debuted [at No. 28 on the TikTok Billboard Top 50]. We’re really excited about that project.

“Blake Shelton signed this guitar. We have been working with him on the Influence Media side since 2022, and we are honored to work with such a luminary.”

Carl Chisolm

You have eight albums by developing acts either out already or coming out this year. With such a small staff, does SLANG have the bandwidth to try to break that many acts?

But they are not all coming at the same time. Some of them, like RX YP, are releasing things later in the year. The focus right now is on TruththeBull, Leaf, Isaia Huron and Camper. When you are working with developing acts, there are no days off, so it’s constant development, building and building. And if things are going in the right direction, then you just keep fueling it to keep it going. But then certain acts are just very creative on their own, so we lean on their creativity and just amplify it. Some acts require heavy lifting and then there’s some light lifting.

Why start a publishing division?

In my mind, it goes hand in hand with the label. The great thing about the publishing side of things is that you can step in at a more accelerated [pace]. We’ve had three No. 1s in the last six months courtesy of our relationship with Future. We also publish Lil Durk and, I love this one, RaiNao. It’s pronounced “right now,” and she’s currently on Bad Bunny’s album. It’s getting huge exposure. She’s working on her new project. We’re excited about her, as we are about our friend DJ Khaled. We are currently his publisher, too.

In addition to a publishing deal with Future, you have partnered with him on other business. What does that entail?

We also have a joint venture with him regarding signing writers. The same thing with DJ Khaled. We get vertically involved with a lot of artists that we work with. For instance, with Future we secured [a deal for] him to be the face of Grand Marnier, which just started rolling out. And we helped Visa organize their first large event at the Louvre and secure Post Malone [for it]. We had RaiNao perform at the Louvre with Post. That’s an example of how we see the world.

“I was drawn to this chess board because it reminds me of my hometown, the best city in the world, NYC,” he says.

Carl Chisolm

How are these deals structured?

It depends. Some of the [artists] are signed directly to us; some of them are [joint ventures]. There’s the distribution deal [with Smith]. We have the ability to be flexible.

Earlier, you indicated that SLANG is funded by Influence Media, which primarily invested in contemporary, established artists. SLANG works with developing artists, a sector of the business that institutional investors typically don’t fund. Does SLANG have the same investors as Influence? How much funding does it have?

Same investors. I am not going to disclose [financing], but you know Influence is well funded. There’s no lack of capital needs. But you have to look at it right. Most companies that start with too much money usually don’t win because, when you have access, you can be very undisciplined. We’re very conscious of the mindset and how we allocate what we spend and invest in. It’s really about discipline and focus. That’s what got us to where we’re at.

This story appears in the Feb. 8, 2025, issue of Billboard.

As of January, Warner Music Group (WMG) executive vp/general counsel Paul Robinson has worked in the legal department of the company for 30 years. During that time, he has seen “three different owners, seven CEOs and we’ve gone private and public two different times,” he says. “There also have been all of these macro changes in the music business” — which is something of an understatement. What hasn’t changed much, he says, is the culture of the company: “It’s always been an artist- friendly, songwriter-friendly culture, and we’ve always had a great relationship between recorded music and publishing.”

Robinson was slated to receive the 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award on Jan. 31 at the organization’s annual Grammy Week luncheon at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. But since the event was canceled in the wake of the Los Angeles wildfires, he will receive the honor at next year’s gathering.

Trending on Billboard

Robinson started at WMG in 1995 after working at Mayer Katz Baker Leibowitz, which at the time did a significant amount of the label group’s legal work. Robinson got the top job in 2006 and helped steer the company through the worst years of the music business, to its 2013 acquisition of Parlophone Label Group from Universal Music Group, and into the streaming-led recovery and a successful 2020 initial public offering.