Cover Story

Trending on Billboard

Romeo Santos arrives wearing a face mask and a hoodie. He’s not sick, just determined to avoid being recognized as he enters our New York studios, and immediately heads to his dressing room with his small entourage. Minutes later, Prince Royce walks through the door, just as quickly and discreetly, with a cap under the hood of his sweater covering half his face.

The two have been seen together in the past, but only as friends on social media. Today, the last Wednesday of October, they’re here to announce something completely different: Romeo Santos and Prince Royce, the “king” and “prince” of bachata, respectively, are finally collaborating, not on a single song, but on an entire album.

Their collaboration has been the best-kept secret in Latin music in years. Appropriately titled Better Late Than Never, the 13-song album will arrive Nov. 28 on Sony Music Latin, where only a small group of people knew of its existence.

Close friends and family were also unaware. (Coincidentally, Royce’s brother, who works as a photographer in New York, only learned of the project when he joined the team that shot the cover for this Billboard Español story and saw both artists’ names on the call sheet.) Many of the musicians who played on the album think it’s by one or the other, since both artists deliberately summoned their sidemen separately and were never seen together in the studio.

The result is pure synergy: “There’s no one taking center stage here,” Santos says. “There isn’t a song where he sings more than me or me more than him.”

I listened to the album the day before, when Santos — as he’s done in the past with Billboard — picked me up in a Cadillac Escalade V and played it for me from beginning to end, responding to my questions and reactions with the joy of someone who knows he has something special in his hands. He’s never been one to share files of his work through email before their release, and he certainly wasn’t going to risk it this time.

Better Late Than Never has the essence of Santos and Royce throughout but also offers something fresh for both artists. There are classic bachatas, more modern takes and mostly romantic lyrics, and the fusion of their recognizable voices is captivating from the first track, which shares the album’s title.

Songs such as “Dardos” and “Jezebel” stand out, the latter displaying strong R&B influences, as well as “Ay San Miguel,” a Dominican palo, and “Menor,” a surprising first collaboration for Santos with an emerging talent, Dalvin La Melodía — who also hadn’t yet been informed about Royce’s participation.

Santos and Royce wrote four of the songs together, starting with “Mi Plan,” penned during a friends trip to St. Barts in 2023, and “Better Late Than Never,” “Jezabel” and “Loquita Por Mí.” The rest were mostly written by Santos, always with Royce’s participation and honest input. But the seed of this production has been germinating since at least 2017, when they recorded the first of three failed attempts that will likely never see the light of day.

“I don’t want to sound cliché or overly religious, but God’s timing is perfect,” Santos says, explaining why now was the right time. “When we started recording the first song seven years ago, there was a little resistance from both of us. I felt convinced at the time… the vibe was there, but then we started evaluating it and [realized], ‘Mmm, this is not the song.’”

“There was a moment where I said, ‘Man, are we ever going to find that fusion, that muse, where we both feel comfortable and can say, ‘This is great?’ ” Royce adds. “And it wasn’t that I doubted it, but it required going in and really delving into it — and suddenly there was a switch.”

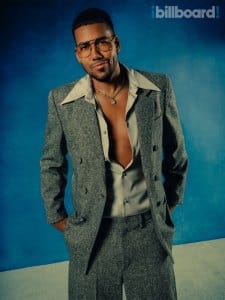

Santos

Malike Sidibe

The launch strategy was equally secretly planned. On Oct. 31, Halloween, Santos, unrecognizable in an Ace Ventura costume, announced on his Instagram account “new album November 28” — with a link in his bio to preorder it — along with a video of him partying in New York with an album in his hands. Days later, on Nov. 10, a massive listening party for his fans scheduled for Nov. 26 at Madison Square Garden was announced on Univision shows such as Despierta América and El Gordo y La Flaca and radio station WXNY-FM (La X 96.3) New York, where listeners could call in to win tickets. According to Santos’ publicist, at the time of the announcement, 7,000 people were online looking for tickets, all assuming that “it’s a [solo] Romeo album.”

Of course, there were no singles or previews. A music video featuring two songs — “Estocolmo” and “Dardos” — will be released simultaneously with the album. To communicate with the director, they used the code names “Batman” and “Robin.”

The collaboration between the two powerhouses is highly anticipated by bachata fans, and the fact that the project wasn’t rushed gives it new urgency and importance. Superstars of the genre from different generations, they are also very different in style — Santos with his sweet, high-pitched voice and use of traditional guitars; Royce with his light lyric tenor and a more pop/urban sound. And both have redefined the genre. Santos, 44, revived bachata when it was considered traditional regional music, giving it a sensual twist with touches of contemporary New York that captivated a new generation. Royce, 36, came later with bachata versions of Motown classics.

Santos rose to fame in the mid-1990s as leader of the group Aventura before launching a brilliant solo career in 2011 with Fórmula, Vol. 1, the longest-running bachata album by a solo artist on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart (17 weeks at No. 1); more recently, he was No. 2 on the Top Latin Artists of the 21st Century list (behind only Bad Bunny). Royce debuted in 2010 with a self-titled set that reached No. 1 on Top Latin Albums, which he has topped five times.

Both born in the Bronx to Dominican parents (except for Santos’ mother, who is Puerto Rican), they met at a family party. “Aventura was huge at the time,” Royce recalls. “I was in my room playing PlayStation. I heard the revolú [commotion], so many people outside. I went out and took a picture [with him],” adding that he was starstruck by the singer’s presence. Now, “This is a full-circle moment. What Romeo and Aventura have done has inspired me.”

“Romeo Santos and Prince Royce are two wonderful artists, two exceptional professionals — and even better human beings — who have dedicated their careers to bringing bachata to the world,” Afo Verde, chairman/CEO of Sony Music Latin Iberia, told me days after the interview. “Each of the songs on this brilliant album reflects the talent, creativity, passion and dedication of both of them. We can’t wait for all the fans to experience this magical album they’ve created together.”

Sitting down to talk for the first time about their most closely guarded secret in an exclusive interview with Billboard Español, Santos and Royce delve into the project, their friendship and the future of the genre that made them famous.

Prince Royce

Malike Sidibe

To begin, who approached whom? Who said, “Let’s do it”?

Romeo Santos: I’d like to take credit, but the truth is, the first person to mention the idea of recording not one, not two, but a whole album, was this gentleman right here. (Gestures to Royce.) And that was literally seven years ago, right?

Prince Royce: A long time ago, yes. I felt a lot of pressure from the public, really. If we make a song, what will it be? It can have pop elements, it can have very traditional elements, it can be a fusion. And I was thinking about how to fuse these two worlds, which, although it’s bachata, are two different styles of bachata. I always thought, “Man, how iconic would it be if we made an album, if we could give everyone these different kinds of flavors and colors?”

Santos: Yes, because that’s a valid point. When he says “the pressure,” it’s like a song will have an audience who will say, “I like this one,” but there will be another type of fan who will say, “Yes, but it’s too slow.” There are those who say, “Yes, but it’s too fast.” “Yes, but it doesn’t have that bitterness or it’s too depressing.” We have a production that fills all the gaps.

You recorded three previous tracks — one in 2017 for Golden, another in 2022 for Fórmula, Vol. 3 and a third later — and none of them were released. After three attempts, what motivated you to keep trying and not give up?

Santos: I think we started evaluating the three songs we had already recorded. “Where was the problem? How could the chorus of these three songs be improved? Was it the verse, the arrangement?” And at least I had the goal of making the songs feel organic, not like we took a song, sent a verse to Royce or vice versa, just to say we collaborated. I think it had to happen this way: three failed attempts to lead to this production. I don’t think I could have worked with Royce in a more ideal way. The best songs we were able to create are on this album.

Royce: I think for me it was, “We shouldn’t rush things.” Nowadays a lot of people lack patience, and I’ve always been very patient. I’m not a quitter, and he’s definitely not a quitter.

Santos: And you know what I respect? He was honest with me about those three songs. I mean, if he had been a hypocrite and told me, “They’re great,” this project wouldn’t have happened. But he was like, “I don’t know, loco, they’re OK, but do you think so?” So I kind of analyzed them. And honestly, every time I presented him with a song, I felt it was better than the last one.

How is it possible that none of this leaked in all these years?

Santos: Well, I’ll just say that in the world of privacy, I’m an expert. I feel very comfortable, even if it’s a little stressful, working on projects with the element of surprise. I’m used to it; I don’t like to prepare people.

Royce: In my case, I just don’t want to jinx it either. I know how he works, I’ve known him for many years. For me it was such an important project that I wanted the element of surprise, I wanted to surprise the audience, I wanted to focus on the project without anyone interfering and simply work.

Santos: Another factor was that we genuinely posted photos and videos together because we were hanging out. I think that when people saw those pictures and didn’t hear any music, they kind of overlooked it. And I didn’t know at the time that this was also what would work as a strategy for us. We managed to keep it a secret for several reasons. Also because technology has changed so radically these days that you can record a production, an album, whatever at home. We didn’t go to public studios; everything was recorded during vacations — we were in a villa with our friends and family, in my home studio in New York. We visited his house many times. That part was easy, honestly.

Royce (left) and Santos

Malike Sidibe

Tell me about “Batman” and “Robin.”

Santos: Ah, that was the code.

Royce: I called it the “Bora Project” with my small team.

Santos: We created this “Batman” and “Robin” thing, but for different aspects; for filming music videos, talking to the director: “Remember, Royce is Robin, I’m Batman.” Until it became second nature. Now I say to him: “What’s up, Robin?”

The fact that the record label hasn’t even heard the album speaks volumes about the creative freedom the label has given you to work together.

Santos: Look, I’m very grateful to Afo [Verde], to the whole Sony team really, but Afo is one of those people who respects the creative side of artists. And I remember sending Afo a message about two months ago, more or less, saying, “Brother, I have a project that I think is going to excite you. You’re going to love it, and I want to share this project with you. I want you to listen to it, to be one of the first.” Afo tells me, “I knew you were planning something,” because my last post was, if I’m not mistaken, on Jan. 8 of this year, and I’ve been ghosting on social media.

How easy or difficult was it working together as two big artists with such distinctive styles?

Royce: From the moment we made that first song [that actually worked], everything flowed for me. It was like there was a whole year where I felt like we were creating something incredible. I was so happy. And I really admire how he pushed me in the studio.

Santos: Thank you. I’m kind of a maniac.

Royce: I hadn’t felt like that in a long time. The fact that I thought I was doing well and [he’d tell me], “No, you can do better, bro,” and just keep at it…

Santos: And vice versa, because I’m so used to directing myself that sometimes you overlook certain things you stop doing as a performer. … The interesting thing about this project is that it has his essence, my essence, but musical proposals that neither of us has offered to the fans before.

Who was more involved in the production?

Santos: I would say I was… [But] I reiterate: He was very key because he trusted me, but also kind of challenged me. When I showed him a song, he was very honest, as he’s always been. So I went in already with that challenge.

What new elements will the audience hear?

Royce: There are new elements like “Dardos,” which has a lot of fusion. There are Afrobeat vibes, tropical vibes, different types of guitars, violins. [The song] “Better Late Than Never” starts off very pop, a cappella. And I think there are many elements, within bachata as well, in the way the guitar is played; there’s a bit of a rock flow.

Santos

Malike Sidibe

What did you think when you heard the album for the first time in its entirety?

Santos: We hugged with happiness.

Royce: I was jumping around, I was tipsy. … I was super excited. For me, it has been an honor to record this album. It has been a very beautiful experience in the studio as well.

Santos: You know what I used to tell him? “This pendejo sings beautifully!” Because I was listening to him from a different perspective. I love producing, and when you create a melody thinking of someone else, in my case, I enjoy it more than I enjoy singing it myself. And sometimes he sang a melody even better than what I envisioned.

Were you already a fan of Prince Royce’s music?

Santos: There’s a mutual respect. I’ve always told him about the songs I love from his repertoire. For me, “Incondicional” is one of those songs that, if you ask me what Romeo hasn’t done in bachata, both with Aventura and as a solo artist, when I heard that song I said, “F–k, mariachi with bachata!” That was great.

Royce, is there a song by Romeo you wish you had written?

Royce: There are many. I’ve always been a fan of “La Novelita” by Aventura. “Infieles.” “Eres Mía”… I think he’s a walking encyclopedia of bachata; he knows every bachata song and has a lot of musical knowledge. And he’s a genius with lyrics, truly.

As friends and colleagues, do you ever call each other for advice?

Santos: Of course. We’ve talked a lot long before this project. It’s a truly genuine friendship.

Prince, what’s the best advice you remember Romeo giving you?

Royce: There are many that I probably can’t say on camera. No, just kidding. (Laughs.) In terms of advice — not just musical; it could be business, it could be personal — we’ve had many conversations and he’s always been, I really mean it, very real with me… And I’ve always respected that.

Santos: I can tell you that one piece of advice he gave me once was, “Don’t take things so seriously.” I have that problem. Sometimes we forget to have fun. Especially when you have a plan, the rollout, marketing, a million things, and I feel like he has that quality. He loves what he does, just like I do, but maybe I’m too… What’s the word?

Royce: Particular, detail-oriented…

Santos: Yeah, sometimes that kind of takes away the fun.

Royce

Malike Sidibe

Let’s talk about the state of bachata. How do you see the genre right now?

Santos: How far the genre has come is impressive, especially when you see artists who aren’t bachata singers navigating this genre of heartbreak. When I listen to Rosalía, Manuel Turizo, Maluma, Shakira, Rauw Alejandro, Karol G, that’s an excellent sign that good work has been done since the beginning.

However, a superstar on the level of Romeo Santos and Prince Royce hasn’t emerged. Why do you think this has happened?

Santos: I think there are a lot of Prince Royces and Romeos in an attic, in a basement, creating the new sound. The thing is, this business isn’t easy. And when I say it’s not easy, it’s not easy for us either. There’s a very essential key that few apply, and that’s perseverance. If you analyze my career, people remember Aventura from “Obsesión,” but we’d been hard at work six years prior to that.

Royce: I think a lot of people always see the success but they never see the failures, what didn’t happen, the doors you knocked on. And I think that nowadays it’s very important to be different… and to bring something that Romeo Santos didn’t bring and that Prince Royce didn’t bring, because they’re already here.

Going back to your wonderful project, an album is usually followed by a tour. Do you plan to go on the road together? What do you envision for that show?

Santos: Obviously, yes, we are considering a tour, God willing, and a worldwide one so people can enjoy both of our repertoires. And when it happens, God willing, we don’t want it to feel like a show where he goes onstage, sings his setlist, then I sing mine. No. We want it to be an experience where, whether you’re a fan of Royce and me or just a fan of him or just of me, it’s a musical journey through both of our repertoires.

What would you say to Prince Royce fans who aren’t Romeo Santos fans, and to Romeo Santos fans who aren’t Prince Royce fans?

Royce: Well, personally, I think they’re going to become fans of all of us.

Santos: You want to know what I’d tell his fans? That they’re going to have to put up with Romeo! (Laughs.) No, but seriously, this is a treat, a gift for both sets of fans, because I think — and I don’t want to sound repetitive — that it’s a production where each song is dedicated to different styles, to his essence, to mine. But there’s something else you’ll notice about it: There’s no one taking center stage here. There isn’t a song where he sings more than me or me more than him. Maybe your favorite part of this particular song is Royce’s chorus, and maybe your favorite part is the pre-hook I did, but I hope you like it, that it evokes some kind of emotion in you in a positive way, because we made it with all the love we could put into a project.

Trending on Billboard

Corinne Bailey Rae has a certain affect on people. She’s the kind of artist that even a brief glimpse of can spark a musical memory even in the most public of places. “I’ll be in an elevator and people see me walk in and they just start whistling ‘Put Your Records On’ to themselves,” Rae laughs. “I don’t even think they notice they’re doing it! But I just love that it has that impact on people.”

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

That particular record, first released in 2006 from her self-titled debut LP, burrows in deep. The song reached No. 2 on the U.K. Singles Chart, appeared on the Billboard Hot 100, and was nominated for two categories at the Grammys the following year: song of the year and record of the year. At almost a billion streams on Spotify alone, its place in the 21st century British pop canon is secure, and its gorgeous melody and empowering message resonate almost two decades down the line.

We meet Rae in her hometown of Leeds ahead of her performance at Billboard U.K. Live at Manchester’s Aviva Studios, home of Factory International. The intimate performance will kick off a series of 20th anniversary celebrations for the 46-year-old musician, which also includes the release of a children’s book Put Your Records On in March, and a show at the iconic Royal Albert Hall in London in October 2026.

Her debut album, Corinne Bailey Rae, was released in February 2006 and peaked at No. 1 on the U.K.’s Official Albums Chart, and at No. 4 on the Billboard 200, an astonishing feat for a British debut solo star. The LP featured another breakout song “Like a Star,” which showcased Rae’s gorgeous vocal capabilities and wistful, impactful songwriting style.

She was soon in the same studios as her heroes, working with them on new music and taking invaluable advice. Stevie Wonder, Prince, Herbie Hancock and Bill Withers, to name a few, all recognised Rae’s talent. Accolades continued to flow Rae’s way – a Grammy win for best R&B performance in 2012, for one – and her second studio LP The Sea (2010) was nominated for the U.K.’s Mercury Prize. Informed by the death of her husband Jason Rae in 2008, the record showcased moments of raw grief, but also hope and healing.

Photography by Shaun Peckham

Shaun Peckham

Her sound, soulful pop with nods to indie-rock and R&B, earned her placements on 50 Shades Darker soundtrack and a brief cameo on Tyler, the Creator’s Flower Boy LP. In 2023, she released Black Rainbows, a sprawling epic that was influenced by an exhibition held at Stony Island Arts Bank in Chicago which focused on Black history in the city. Fans and critics alike were stunned by the LP, one that was packed in feminist punk (“New York Transit Queen”), spiritual jazz (“Before The Throne of the Invisible God”), and big tent rave (“Put It Down”). Reviewers commended the stark left-turn, and another Mercury Prize nod beckoned.

It was on that awards night – ultimately won by Leeds’ band English Teacher for This Could Be Texas – that Rae’s impact and longevity came into view for her. “For some reason I was behaving like such a mother hen… totally unsolicited, by the way,” she laughs, reminiscing on meeting fellow Yorkshire artist Nia Archives and country-pop crossover star CMAT. “I was going up to these cool young musicians like, ‘Hi, you don’t know me, but here’s some advice: don’t feel like you have to rush your second album, do your thing.’”

Rae’s advice, no doubt, was heeded. Her stellar career has thrown up situations that she could only have dreamed of when she was gigging in the indie-rock band Helen in Leeds in the early ‘00s, and seen her overcome the most difficult of challenges. Almost twenty years to the day since “Like A Star,” her debut single, was released, she reflects on the lessons she’s learned, the rewarding creative journey she’s been on – and what comes next.

We’re speaking around the anniversary of your debut single. How do you look back on that era?

I have really fond memories of making “Like A Star.” I think it was quite different for the time. It was more like my true voice, and quite conversational and small. It wasn’t what you might think is a ‘pop voice.’ A lot of doors had been opened by people like Björk or Martina Topley Bird [collaborator on Tricky’s Maxinquaye] and that made me realize there were all these different ways to sing. It didn’t have to be like Mariah Carey-style, with that unreachable big singing voice.

Once “Like A Star” was released, things moved quickly…

The pace of it was quite staggering. The residency I was performing at in London over the course of four Thursdays went from not being sold out in week one, to queues around the block, and then I ended up performing on [BBC Music show] Later… with Jools Holland so early on in my career. This was all before the album came out, so I thought, ‘Wow, I keep getting asked to do stuff, so I’ll just say yes to everything.’ The album came out and I remember being on tour and someone telling me that the LP had gone to No. 1. I was like, ‘Wait what?’ I just couldn’t believe it.

That’s all you want as a musician is to get somewhere. And I had tried for a few years with my band and we didn’t get much love. This was my first record and it felt like it’d gone from 0 to 100.

Did you cope with the attention OK?

I think I did, you know. I was a little bit older at 25, so it wasn’t like I was 19 and still figuring out who I was. I had good friends and had good advice from my manager and friends. I also feel like when I was in the US, certain people would look after me and lean into me and give some words of advice. Whether that was Questlove, Prince, Stevie Wonder, just these people who were gods of music, but also a lot older than me.

I remember Herbie Hancock specifically saying not to rush into the second record and to take a minute. I thought that was really good advice to not feel the pressure, or feel that everyone would fall out of love with me.

When I came to my second record I felt that I had a different thing to say. That was then the moment to keep pushing out. Even when we played live at that time, I always added in this Led Zeppelin cover of “Since I’ve Been Loving You.” I wanted people to see I could do other things, and make sure that I wasn’t in a box.

Photography by Shaun Peckham

Shaun Peckham

Your life changed quite significantly between album one and two, following the loss of your husband. How did that event inform what you were doing creatively?

“When I look back at [debut LP Corinne Bailey Rae], it’s on the other side of… not a wall, but a divide between my two adult lives. That moment [Jason’s death] felt like the end of what that first album term was. I felt like my life was divided between the before and after of that.

As well as changing my life, it also changed my career in a really big way. I knew that I wasn’t really robust enough to be in an industry ‘capitalizing’ on the big industry success of the first record, and setting up sessions with all these big names anyway. I just wasn’t in that place, and the label really knew that and I think that they really left me to it.

But by the time the third record came around [The Heart Speaks in Whispers, 2016] they were really on my case. That put so much pressure on me, which was really difficult. That made it take miles longer and it wasn’t what they wanted and it was more tricky.

In the past you mentioned that the press expected a certain response to Jason’s passing, but you didn’t give them what they wanted…

It was a very aggressive time journalistically, but I just feel really lucky that I’ve had good people around me. I knew Amy [Winehouse] and that was really frightening to see that side of people, and to see the vulnerability of going from being a cool jazz singer, to the biggest thing in British pop music. That is not a place you desire to be – no one wants to be there. Plus, there was a need to tear down successful people in this country, which has been so strong for years, and it was definitely like that for women at that time.

Photography by Shaun Peckham

Shaun Peckham

Black Rainbows was a record that really expanded your sonic palette. How do you look back on that record?

I love that album so much. It felt really special to me because it was so freeing. I’d just come out of my label deal and I wasn’t really looking for anything to do next.

But I was invited to come to the Stony Island Arts Bank [a Chicago-based archive of Black art and culture], and I was just so inspired. All the time we were in there, these people were coming in and all of these black performers, photographers, documentary-makers. I ended up writing about all of these images and stories from Chicago’s history just to try and make sense and process what I’d seen.

That LP was considered something of a ‘left-turn’ for you. Did you feel that was a fair assessment?

It was a left-turn in terms of what I would share, I guess. In my band , I used to play a lot of indie music and heavy stuff. And before that, I was in a church where I’d play these big wig-outs that stretched on for over 20 minutes. But sharing that felt very freeing and felt new.

Black Rainbows was initially going to be a side project, and it wasn’t going to have my name on it – I didn’t want to feel like I was messing up what I’d done before. But I like that music allows you room to grow to gather an audience that trusts you. 20 years is a long time in anyone’s life, and you don’t want to stay still and not change, or to be the same person at 46 that you were at 26.

What changes have you seen in the music industry over the past 20 years?

The biggest change is that people don’t think you should pay money to have music. It’s such a different paradigm, but music is almost a conceptual thing. There’s a generation of people who think that music just happens and appears on streaming services, their favorite shows or wherever. There’s a real disconnect between the people who make the music and the listener.

I can’t say how that might change but at the same time, if it doesn’t all we’re going to get is the music of a really narrow group of people: artists who can do a really good sponsorship with a trainer brand to fund their creative work, or rich people with privileged backgrounds. We’re missing out as a society on what working class people or struggling artists might think if we’re not going to pay artists to do what they do.

Tell us about the children’s book Put Your Records On that you’re releasing in 2026…

I was reading a lot of children’s books for my children when I came up with the idea – and I just thought that I could say something here. I wanted to speak about music and the feelings that different songs can conjure, and that there’s a song for every feeling that you’ll ever have. Music has always been a way to explore my feelings and a way to free me. I’m finding writing, with the pen and the words, really exciting and liberating. I’d love to do more in the future.

And musically, are you working on a new project at the moment?

I am working on new music. That’s the thing I’m really excited about is trying to work out: what the sound and direction is, what I want to say and who it’s going to be with. I feel really inspired right now, and Black Rainbows has really freed me into not overthinking things – that’s been really important.

Photography by Shaun Peckham

Shaun Peckham

Shoot production by WMA Studios. Photography by Shaun Peckham. Photography assistance by Jack Moss. Grooming by Bianca Simone. Shot at Light Space Studios, Leeds.

Trending on Billboard

Rosalía offers an exasperated laugh as she sits down, having tried on a variety of equally stunning outfits only to end up in the casual clothes she arrived in: black pants and a camo jacket lined with fur. It’s the same jacket she was spotted wearing at a Parisian cafe in early October, seated alone with a cup of tea while poring over the sheet music of a song from the 1900 Puccini opera Tosca.

The Barcelona-born singer’s candid moment with the canonical tragedy was significant — one of many subtle nods that she was pursuing something outside the typical parameters of modern mainstream music. Rosalía studied musicology in college, and over the last eight years has often meshed a wide variety of genres and influences in her songs. But for someone who rose to global fame on the cutting edge of culture, studying the musical notation of a century-old opera communicated a pointed message.

Weeks later, fans began to understand why. On the evening of Oct. 20, she took to Madrid’s Callao Square with giant projector screens, where a countdown unveiled the release date for her fourth album, Lux (Nov. 7 on Columbia Records), as well as its cover art, which features Rosalía dressed in all white, wearing a nun’s habit and hugging herself under her clothing.

Every move Rosalía has made over the past three years while crafting Lux has been considered, intentional and entirely in her own world. Having risen to fame with the flamenco-inspired pop of her Columbia debut, 2018’s El Mal Querer, she flipped the script with her eclectic, energetic 2022 album, Motomami, which spanned pop, reggaetón, hip-hop, electronic and more and became her first album to chart on the Billboard 200, peaking at No. 33. But Lux is something different: an orchestral, operatic opus recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra that blends history and spirituality and experiments with form, language (she sings in 13 different ones throughout the album’s 18 tracks) and the very idea of what is possible for a major recording artist in 2025, for a project that’s more Puccini than pop — not that it doesn’t have its moments of catchy relatability.

“It’s like an album she wrote to God — whatever each person feels God is to them,” says Afo Verde, chairman/CEO of Sony Latin Iberia, which works with Rosalía alongside Columbia. “This is an artist who said, ‘I want to walk down a path where few walk.’ And when you navigate inside the album, you completely understand the genius behind it.”

Araks bra, Claire Sullivan skirt, Louis Verdad hat.

Alex G. Harper

Rosalía spent the better part of three years crafting Lux’s lyrics and instrumentation, drawing from classical music, native speakers and instrumentation, and the giants of the past — women including Saint Rosalia of Palermo; the Chinese Taoist master/poet Sun Bu’er; the biblical figure of Miriam, sister of Moses; and even Patti Smith all figure into its cosmology — to create something that feels both worldly and otherworldly, a distinct take on navigating life’s chaos. It was also a period where she experienced personal and professional changes: She broke off her engagement to Puerto Rican reggaetón star Rauw Alejandro, switched management and landed her first big acting role in the forthcoming third season of hit HBO series Euphoria, all while immersed in making the album.

“In general, just to be in this world is a lot; sometimes it’s overwhelming,” she says on a fall day in Los Angeles. “In the best-case scenario, the idea would be that whoever hears it feels light and feels hope. Because that was how it was made and where it was made from.”

“This record takes you on a complete journey; the singing on it is just astounding,” says Jonathan Dickins, who runs September Management, home to Adele, and who began representing Rosalía in June. “I think she’s a generational artist. I’m lucky enough to have worked with one, and now I’m lucky enough to work with another. She is an original.”

To make Lux, Rosalía relied on several of her longtime collaborators — producers Noah Goldstein and Dylan Wiggins and engineer David Rodriguez among them — and tasked them with taking a new approach. “The whole process helped me grow as a musician, as a producer, as a sound engineer,” says Goldstein, who has also worked with Frank Ocean, Jay-Z and FKA twigs. “That’s one of my favorite things about working with Rosalía: I’m always learning things from her.”

She also tapped new collaborators such as OneRepublic singer and decorated songwriter Ryan Tedder (who spent three years DM’ing Rosalía, hoping to eventually work together) and urged them to push their boundaries. “For an artist to give me the freedom to just express myself in that way, God, that is the most fun I’ve ever had,” says Tedder, who has worked on mammoth albums by Adele, Beyoncé and more throughout his career. “I’ve been asked by everybody, ‘What does the new Rosalía stuff sound like?’ And I literally say to everybody, ‘Nothing that you possibly would imagine.’ ”

Alex G. Harper

Fans got their first taste of Lux when Rosalía dropped the single “Berghain,” which features Björk and Yves Tumor, in late October. The song kicks off with a string orchestra introduction followed by a Carmina Burana-like chorus and then Rosalía singing in an operatic soprano voice — in three languages.

For Rosalía, challenging preconceptions about the type of music she, or anyone, can make is part of the point — thinking outside the box, following her inspiration and constantly learning, finding and creating from a place of curiosity and openness to new experiences and ideas. “I think that in order to fully enjoy music, you have to have a tolerant, open way of understanding it,” she says. “Because music is the ‘4’33” ’ of John Cage, as much as the birds in the trees for the Kaluli of New Guinea, as much as the fugues of Bach, as much as the songs of Chencho Corleone. All of it is music. And if you understand that, then you can enjoy in a much fuller, profound way, what music is.”

When did you start working on this album?

I don’t think that it’s easy to measure when something like this happens or starts. The album is heavily inspired by the world of mysticism and spirituality. Since I was a kid, I’ve always had a very personal relationship with spirituality. That’s the seed of this project, and I don’t remember when that started.

How did you approach Lux differently?

This album has a completely different sound than any of the projects that I’ve done before. It was a challenge for me to do a more orchestral project and learn how to use an orchestra, understand all the instruments, all the possibilities, and learn and study from amazing composers in history and say, “OK, that’s what’s been done. What can I do that feels personal and honest for me?” And also the challenge of having that inspiration in classical music and trying to do something that I haven’t done before, trying to write songs from another place. Because the instrumentation is different from all the other projects I have done. But also the writing, the structures, it’s very different.

Chloé dress, shoes, and scarf.

Alex G. Harper

After Motomami, your success and fame hit a new level. How did that help you make this album?

All the albums I’ve done helped me be able to be the musician I am today and make this album now. Lux wouldn’t exist if I hadn’t taken the previous steps. Each album helped me release something, to free myself as much as possible. Every time I go to the studio, it’s from wanting to play around, try something different, to find different styles of making songs. I always try to stay open.

You’ve said Motomami was inspired by the energy of L.A., New York, Miami. What was your mission in making Lux?

It’s made from love and curiosity. I’ve always wanted to understand other languages, learn other music, learn from others about what I don’t know. It comes from curiosity, from wanting to understand others better, and through that I can understand who I am better. I love explaining stories. I like to be the narrator. I think as much as I love music itself, music is just a medium to explain stories, to put ideas on the table. So that’s what this project is for me. I’m just a channel to explain stories, and there’s inspiration in different saints from all across the world. So you could say it feels like a global thing, but at the same time, it’s so personal for me. Those stories are exceptional. They are remarkable stories about women who lived their lives in a very unconventional way, of women who were writers in very special ways. And so I’m like, “Let’s throw some light there.”

What I know is that I am ready, and this is what I needed to do. What I know is that this is what I was supposed to write about. This is my truth. This is where I am now.

What contributes to the fact that the album feels so global is you sing in 13 languages on it.

It took a lot of writing and scratching it and sending it to someone who would help me translate and be like, “This is how you would say this in Japanese. This is how it sounds.” There were so many things that I had to play with and take under consideration. Because it’s not just writing. It’s not just on paper. It has to sound good. There’s a big difference for me when I write, for example, a letter for somebody that I love than if I write a song. It has to have a certain sound, a certain intention of musicality.

It was a big challenge, but it was worth it. It made me grow so much. And I feel like every word on this album, I fought for it, I really wanted it, and then I waited for it, and then it came. It took me a year to write just the lyrics for this album, and then another year of arranging music and going back to the lyrics and retouching. It took a lot of effort searching for the right words: “How is this not just going to be heard, but also, if you read it, how does it feel?”

Rosalía photographed September 24, 2025 at Quixote Studios in Los Angeles. Colleen Allen top and skirt.

Alex G. Harper

The lyrics read like a novel.

There’s a whole intentional structure throughout the album. I was clear that I wanted four movements. I wanted one where it would be more a departure from purity. The second movement, I wanted it to feel more like being in gravity, being friends with the world. The third would be more about grace and hopefully being friends with God. And at the end, the farewell, the return. All of that helped me be very strategic and concise and precise about what songs would go where, how I wanted it to start, how I wanted the journey to go, what lyrics would make sense.

Each story, each song is inspired by the story of a saint. I read a lot of hagiographies — the lives of the saints — and it helped me expand my understanding of sainthood. Because my background is Catholic from my family, so you understand it through this one [lens]. But then you realize that in other cultures and other religious contexts, it’s another thing. But what surprised me a lot was that there’s a main theme, which is not fearing, which you can find shared across many religions. And I think that’s so powerful because probably the fears that I have, somebody on the other side of the world has the same ones. And for me, there’s beauty in that, in understanding that we might think that we’re different, but we’re not.

All of these songs are very personal, but “Focu ’ranni” feels especially so. What was the experience of writing that one?

I found out that there’s this saying by Santa Rosalia de Palermo — she was supposed to get married and then she decided not to; she decided to dedicate her life to God. I thought that something in that was very powerful. I researched her story, and that’s why there’s some Sicilian thrown in that song. It was a challenge to sing in that language. That was a challenging song to do and to sing, but I feel grateful that it exists.

You create a world, and a sisterhood almost, on this album. How does a more playful song like “Novia Robot” fit in?

There was this woman who was very inspiring named Sun Bu’er; she dedicated her life to becoming a teacher of the Tao. And the way she lived her life was unconventional at that time. I thought there was something powerful about her story. Apparently, in order to make a journey, she destroyed her face to be able to travel safely. And she had a partner, she had a family, but she decided she wanted to dedicate her life to spirituality. It was so bold and courageous. And at the end of that song, you hear another voice, which is in [Hebrew], that’s inspired by Miriam, this figure who led an entire people and was a rebellious woman and considered close to the idea of sainthood in Judaism. So I thought that it was cool to have those two voices, the same way how in opera there are so many voices co-existing. So I thought in that song that could happen with that playfulness, yes, and playing with the sound of how Chinese Mandarin would sound.

The album is so operatic and orchestral. How did you begin to immerse yourself in those styles and find the people that you worked with to deliver that?

They’re the people I feel comfortable with, so I love sharing time with them in the studio. For example, I worked on [Lux song] “Mio Cristo” for months by myself in Miami and L.A., and I delayed the moment when I would share it. I wanted to make a song that was like my version of what an aria could be. So I remember just going to the studio after so much work, after so much back and forth with an Italian translator, and I [had been] improvising on the piano, trying to find melodies, to find the right chords and notes. I went to the studio and I shared it with Dylan [Wiggins], with Noah [Goldstein], with David [Rodriguez], and I remember they were like, “Yes. That’s the song. There it is.” So it’s been a lot of isolation on one side — a lot of writing — and then on the other side a lot of collective effort in the studio.

It’s such a vivid album. How are you plotting out how it will look visually?

My sister and I work together a lot. I’m very lucky that I get to just keep playing around and having fun like how we used to when we were kids. Her and I love recommending things to each other, we send books to each other. Having a project together is something I feel so grateful about, the fact that my family is involved — my mother, my sister, they’re very important people in my life, and I feel like I can share everything with them. And on the visual side, it was just playing around with references and imagination, just trying to think, “What can we do with this?” Just playfulness. That’s how I think the best things happen — out of joy.

Have you given any thought yet to what a live performance of this album would look like?

Thoughts are never lacking, but we’ll see. I don’t want to think too much how that would look until that really is happening, if that makes sense. But there’s definitely a lot of creativity with how this could be translated to the stage.

Alex G. Harper

At the same time you were working on this, you were filming the third season of Euphoria, your first major acting role. Was that difficult?

It was very challenging to do both. I was recording the album and producing and checking mixes, everything, while I was shooting Euphoria. I had to divide my mind between both and it was also the first time that I was doing something like this — preparing a character, studying lines. These are new things for me and I’m not used to it. It’s very different from making an album and making music. For some reason, I didn’t completely go crazy, and we’re still here.

Did any of that experience seep into the album?

[Euphoria creator] Sam [Levinson] and I are both very sensitive people. For some reason, whatever he’s creating for me resonates for this moment. When we were shooting, when we spoke about the [show’s] story, I didn’t know him that well. I really admired his work, but I didn’t know how his mind worked, how he is as an artist. I realized he has so much sensibility and I connected so much with that, not just with his work, but also him as a person.

How did that role come about?

I shared that I really wanted to start acting, that it was something that I would love to do. The only thing I had done was [the Pedro] Almodóvar [film Pain and Glory in 2019], and when I was 16 I studied theater for a year. I feel like being a musician and being onstage is being a performer, but I had never experienced it as being filmed, learning lines; it’s a very different job. I had done it with Almodóvar, but I was like, “I would love to do it with somebody like Sam, somebody that has a vision as strong as him. Or someone like Sofia Coppola.” So then I heard the third season was happening and I was like, “I would love to audition.”

You had to audition?

Of course! Because I’m not an actress, and that was really scary. But at the same time, something told me that I was supposed to do it. So I did an audition tape, then met an audition person and then something else, and then it happened.

Rosalía photographed September 24, 2025 at Quixote Studios in Los Angeles. Araks bra, Claire Sullivan skirt, Louis Verdad hat.

Alex G. Harper

At the end of your album, you address the concept of death. Are there things in your life that you worry about not having enough time to do?

No. Whenever God decides it’s time to go, it’s time to go. Whatever I have come here to do, I feel like I’m doing; whenever I have to leave, I will leave. That’s how I try to live. I would love to know how it feels to be 100 years old, but that’s not on me to decide. But I would love to keep writing, I would love to keep making music, I would love to keep learning how to cook better, I would love to keep studying — one day I would love to go to college again and study philosophy or theology — and I would love to keep traveling. There are so many times that I travel and feel like I haven’t seen enough or haven’t had enough time to just experience places.

But for now, I’m dedicating myself to my mission, which is making albums and performing. And for me, performing is an act for others. I don’t like touring. I like to be onstage and I love my fans, so I do it. But I love being in my home, calm, reading, cooking, going to the gym, lifting weights and going to sleep. Literally, that makes me so happy; I don’t need a lot. (Laughs.) When you travel, it’s much harder; psychologically it’s a challenge, always. But I also know that there are other jobs that have so much complexity and challenges, and I feel so grateful that I can be a musician.

What’s the biggest challenge that you feel like comes with this career?

The price you pay, the sacrifice, the amount of moments that you lose with your family, with your loved ones. My grandpa died when I was at the Latin Grammys in 2019, and I was about to perform when I found out. I couldn’t even be at the burial. Those things, I’ll have to live with the sadness and the regret of not being there. Those are things that are not the good side of being a musician: always struggling, always being committed to whatever you’re doing, to the people who are there in the audience that night who paid for their ticket to see your performance. Maybe that’s the thing they’re looking forward to the most that week. The price is really high, but this is what I chose, and I’m fully conscious that this is the decision I’ve made.

In releasing this album, what would success look like for you?

Success, for me, is freedom. And I felt all the freedom that I could imagine or hope for throughout this process. That’s all I wanted. I wanted to be able to pour what was inside, outside. And those inspirations, those ideas, make them into songs. I was able to do that, and I will not ask for more.

This story will appear in the Nov. 15, 2025, issue of Billboard.

Trending on Billboard Rosalía offers an exasperated laugh as she sits down, having tried on a variety of equally stunning outfits only to end up in the casual clothes she arrived in: black pants and a camo jacket lined with fur. It’s the same jacket she was spotted wearing at a Parisian cafe in early […]

Trending on Billboard

On a late-spring night, Downtown Miami was a place out of time. Thousands of people gathered dressed to the nines, the women rocking sequined gowns and kitten heels, the men wearing tailored suits and polished dress shoes. Their attire fused Puerto Rican culture and Mafia fantasy and seemed beamed in from decades ago — but the crowd entering Miami’s Kaseya Center on this warm evening wasn’t there for an act of yesteryear, but rather one of the hottest arena artists on the planet.

“It was a whole vibe,” Rauw Alejandro says over Zoom months later, now off the road and back home in Puerto Rico. “It felt like we went back to the past and you can feel that energy. It’s not mandatory, but if you dress up, you’ll have more fun because you’re immersed in the story. You’re literally traveling to that time and age.”

Like many arena and stadium stars today, the 32-year-old reggaetón star encouraged audiences to follow a special dress code for his show. His Cosa Nuestra tour this year channeled the elegance and glamour of a certain 1970s New York, along with the Cosa Nostra that ruled it. For the shows, he constructed an alter ego: Don Raúl, a suave Nuyorican hipster living in the Big Apple.

“I lived in New Jersey at an uncle’s house after Hurricane Maria [in 2017],” says the artist born Raúl Alejandro Ocasio Ruiz, who considers New York his second home and whose father was born in Brooklyn. “I went there to work for a year and took the train to the city to continue to do my music. I’m in Puerto Rico most of the time, but for work, my base is New York. So I moved back there three years ago when I was looking for inspiration for this new chapter. I was immersed in the culture… all the Broadway shows, jazz clubs, speakeasies, and I worked with that aesthetic for my new project.”

Rauw Alejandro will appear in conversation during Billboard‘s Live Music Summit, held Nov. 3 in Los Angeles. For tickets and more information, click here.

With Cosa Nuestra, Rauw created a world for his fans to soak themselves in — one far from a typical reggaetón concert. The Broadway-inspired, four-act show featured sophisticated costumes, a six-piece live band and eight dancer-actors, all part of a storyline driven by Rauw’s biggest hits.

The show follows Rauw’s Don Raúl as the young immigrant tries to make it in the big city — and along the way falls in love, experiences betrayal and even gets arrested. “What makes my tour unique is the smoothness of the storytelling and how it connects with my songs from the beginning to the end,” Rauw says. “I think I’m setting the bar very high.”

The ambitious concept has yielded returns that would please Don Raúl. Across spring and summer legs in North America and Europe, respectively, the Live Nation-produced tour grossed $91.7 million and sold 562,000 tickets, according to Billboard Boxscore, making Rauw’s fifth tour the most lucrative of his career. He just returned to the road for dates in South America and Mexico and will wrap the tour with a five-date residency at San Juan’s Coliseo de Puerto Rico José Miguel Agrelot — his second multidate run at the venue this year — in November.

With its achievements, the trek, in support of Rauw’s fifth studio album, 2024’s Cosa Nuestra, has mirrored his chart success. The album and tour take their name and inspiration from another Cosa Nuestra, the genre-defining 1969 salsa album by Willie Colón and Héctor Lavoe, two influential salsa figures who revolutionized the golden era of big-band artistry and popularized the genre in the ’60s and ’70s with the culture-shifting Fania label. For the set, Rauw fused his signature perreo, electro-funk and R&B with bomba, salsa and bachata for a sound entirely his own.

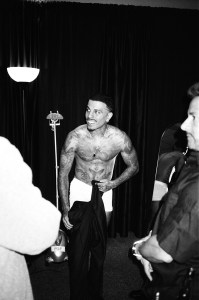

Alejandro backstage at Kaseya Center on May 30 in Miami.

Marco Perretta

Audiences responded: Upon its November release, Cosa Nuestra debuted at No. 1 on Top Latin Albums and Top Latin Rhythm Albums and at No. 6 on the Billboard 200, marking his highest-charting set, and first top 10, among five career entries. In late September, Rauw unleashed another album, the “prequel” Cosa Nuestra: Capítulo 0, which debuted at No. 3 on both Top Latin Albums and Top Latin Rhythm Albums.

“The meaning of Cosa Nuestra is so big that I have to release 20 albums to explain its concept. There’s no time to do that in just one album,” Rauw says with a laugh. “I’m going to continue to bring my roots to the world. Nowadays, I feel so connected with my people and am very proud of where I come from. I don’t have to look outside when I have everything here.” This is how Rauw’s globe-trotting tour came together.

‘I Want To Work With the Best Teams in the Industry’

Rauw’s 2023 Saturno tour grossed $50.2 million but had its entire Latin American leg canceled due to technical and logistical problems. Duars Entertainment, the company led by Rauw’s then-manager, Eric Duars, produced the tour through its Duars Live division, and afterward, Rauw and Duars parted ways. Rauw’s new team, led by the trifecta of co-manager Jorge “Pepo” Ferradas (who has managed Latin stars including Shakira) and longtime Rauw associates Matías Solaris and José “Che” Juan Torres, is now helping him streamline his operation.

Rauw Alejandro: For me, it was very frustrating not completing the Saturno tour. I’m not going to lie: There were months that I would cry in my shower, in my bed, f–king frustrated because I put so much effort in what I do. I took my time. I trained a lot. There were many things that were out of my control. My old team was a mess and disorganized. I consider myself one of the best artists right now, so I want to work with the best teams in the industry.

Jorge “Pepo” Ferradas, co-manager: I received a call from one of Rauw’s lawyers and [his] business adviser, “Che” Juan, and he told me that Rauw was creating a company where he would, in a sense, be the director. I met Matías [Solaris], Rauw’s personal manager, and we created this trilogy management format. We are three different people who have been able to tackle all areas of the business, slightly breaking the norm of having a single manager.

Rauw: After having the same management for seven, eight years, for me, it was a huge change in dynamic in my work and it was challenging. I was kind of scared because there were things I didn’t know how to do. But now, it feels nice to have a team who believes in you and in your project. They’re not afraid to lose anything; they just want an artist that can create and bring new things to the table.

Alejandro (left) with his stage manager Orlando backstage at Kaseya Center.

Marco Perretta

Alejandro (center) with family and friends backstage at Kaseya Center. From left: friend Francis Diaz, uncle Rodny, mom Maria Nelly, and assistant Jose Rosa.

Marco Perretta

Ferradas: Rauw was determined to grow in every area. He knew he was facing the challenge of making perhaps the most important album of his career to date, and we understood that to present it live, we had to put on the best possible production that would reflect the artist’s growth. We had to find strategic partners, in this case Live Nation and UTA [where Rauw signed in 2024], who knew how to think, dream and execute on a grand scale.

Rauw: You either get stuck or you evolve. Now I’m doing the music that I want with the people that I want and I feel really happy. This has been the best year of my career.

‘He Wanted Them To Be Classy With Suits and Ties’

When Rauw headlined New York’s Governors Ball festival in 2024, he introduced his new alter ego by wearing a pinstripe suit reminiscent of a ’70s Nuyorican hipster. But Don Raúl had been in the works well before that — and Rauw would have to wait a little longer to bring him to the masses.

Ferradas: Planning and timing are key to making things happen. Often, the public doesn’t see or isn’t aware of how much time a project like this takes.

Felix “Fefe” Burgos, choreographer: Rauw and I always have conversations, and when he first proposed this entire [Cosa Nuestra] concept to me, I thought, “Oh, damn!” He’ll be working on an album, and we’ll start talking about the next one. As we’re working on one tour, we’re already working on another one. We knew from a long, long, long time ago that he was going to release an album that was going to be very band-incorporated. When he was doing [2022 album] Saturno, he was already talking about Cosa Nuestra.

Adrian Martinez, creator and show director/co-founder of creative agency STURDY: A year before the [Cosa Nuestra] tour started, Q1 of 2024, I went to New York to meet with Rauw and start talking about what Cosa Nuestra was going to be. He played me [lead single] “Touching the Sky” for the first time and told me that was going to be the vibe. We walked around the city that same night for about two hours, went to different parts, took photos of buildings and talked about architecture. We went to eat, went to a bar and talked about what we wanted to do. These were all super-early ideas, but we had a year to develop [them]. It gave us an ample amount of time to really home in on the details.

Rauw: It was difficult to create this tour. I like to wait for people to listen to the album and see how they respond before I create the show rundown — which songs am I going to take out of my old catalog? Which are the new songs I’m going to add? It’s a whole lot of thinking to make it smooth and nice, and that takes time. It all started after my performance at Gov Ball in June.

Alejandro performs at Viejas Arena on April 30 in San Diego.

Marco Perretta

José “Sapo” González, musical director: Right before Saturno came out, Rauw was already saying he eventually was going to need a full band but that he wanted them to be classy with suits and ties. This all became reality for his performance on the Today show in [2024] and he never looked back.

Ferradas: Last year, the strategy was to do festivals and TV specials, always knowing that the tour would be scheduled for 2025. He [played] several [festivals], including Sueños in Chicago, Global Citizen in New York and [played] the MTV Video Music Awards for the first time.

Mike G, partner/agent, UTA: His team invited us to a one-week camp to share ideas and strategies, so they really let us form part of his overall business, which I think gave us an advantage as agents. The more we know about a project, we can plan a lot better.

Rauw: As an artist, what helps me a lot is to plan my work two to three years ahead. I don’t like to repeat myself in projects. I like to do different music, and having a map and being organized helps me go through it. I get a lot of inspiration and I’m always taking notes. Yes, I’m in this chapter right now, but I’m already planning my next one. I think that helps me [remain] innovative and versatile in this industry.

‘It’s a Broadway Show in an Arena’

Rauw knew he wanted a special live treatment for the world he had created on Cosa Nuestra. But translating the album to the stage — and with the elaborate, Broadway-caliber production he wanted — was tough.

Martinez: We knew it was going to be all New York. It was inevitable. Immediately, we thought of the things that were important to New York and how these stories were told. Personally, I thought of West Side Story. How do we take inspiration from that to give an ode to what’s come before? Rauw and I even went to see The Great Gatsby together [on Broadway]. Then we sat together for two straight days to write the script and [develop] what the narrative was going to be. We had a blank page up on his TV, and we went through all the acts.

Mike G: His tour is a movie, very cinematic. I think he set the bar very high. It’s about cultural ownership, authenticity, about pride. The production feels very personal. You follow the storyline, you get invested in it, and that’s hard to do during a concert. He’s telling a story while playing some of his best records.

Rauw: Cosa Nuestra is not a stadium show. It’s a Broadway show in an arena. I would even say it’s the biggest Broadway show. In a stadium, you [wouldn’t] be able to see all the details because it’s too big. We planned this show for arenas.

Alejandro performs at Toyota Center on April 17 in Denver.

Marco Perretta

Alejandro performs at United Center on May 9 in Chicago.

Marco Perretta

Burgos: The part I felt was challenging was, “How do we make a concert into a Broadway play?” Because at the end of the day, this isn’t a Broadway play. This is a concert, but you want it to feel like a show.

Martinez: There were so many props, production elements that all had to work together so closely. We were down to milliseconds on transitions. The Saturno [tour] was also time-coded but [had] less going on and more just [relied] on him singing, dancing and interacting with the crowd. There weren’t really any theatrics [on that tour] compared to what we did in Cosa Nuestra.

Burgos: Everything in that show is choreographed. We needed the cues to be perfect because there was very little room for freedom in certain aspects. When we did the choreography for [the tours supporting 2020’s] Afrodisiaco and [2021’s] Vice Versa, yeah, you can floor-hump because that was the vibe, but for Cosa Nuestra, he wanted it to be classy. We wanted the choreography to be sensual but not vulgar.

Rauw: Throughout my entire career, I’ve been focusing on being one of the best performers in the world, and I focused a lot on dancing, but having a live band was my dream. It allowed me to explore different sounds while feeling more classic, more clean, more elegant.

González: The band unifies all of his catalog into this new universe. The best example is what we did with [Saturno’s] “No Me Sueltes,” which now passes through a bunch of musical genres and fits right into Cosa Nuestra. The band also adds versatility and energy and a vibe. It’s not a background band — everything is about enhancing Rauw and making that connection with the fans stronger.

Martinez: We were all feeling like we were taking a huge risk. This was never done in the genre. How were people going to react to the pace? When you break down the show, it’s so different from your typical concert. We said, “As long as we’re all on the same page about this, it could be great, or not” — but we believed in it.

Alejandro performs at Toyota Center on May 6 in Houston.

Marco Perretta

Alejandro performs at The O2 Arena on June 17 in London.

Marco Perretta

Sean Coutt, merchandise creative director/founder of fashion label Pas Une Marque: Cosa Nuestra is almost a personal story of Rauw and his upbringing in New York, so creatively, [the merchandise] had to tie in. Rauw approved every single design himself. That really shows that he’s very dedicated to his fans and that he cares about what we’re putting out. He really wants that to be an opportunity for fans to see that he’s not only creatively onstage but also 360.

Rauw: I make the final decisions on everything related to the tour: the music, the stage, the band, the dancers, the lighting, the props. I’m very involved with all the teams. I have a huge team who are the best, but I’m very picky and need to see everyone’s work.

Ferradas: Rauw represents this generation of artists who are superinformed, involved and very clear about what they want. He always fought to achieve what he wanted, and he corrected us every step of the way so things would come out as he envisioned it. It came naturally. He’s very involved in the artistic side of things.

‘He’s a Cultural Icon’

With a new team in tow that’s helping him reach an even larger global audience, Rauw is gearing up for his next career move — and a much-needed vacation.

Ferradas: We knew we wanted to start in the United States; it was key to be able to showcase the show there and hold 30 concerts, including [four dates in] Puerto Rico. We knew we had to go to Europe in the summer and continue in Latin America, where the most loyal fans are, and then come back and finish in Puerto Rico.

Mike G: In London he played at the O2 Arena for the first time, and Germany is always a unique market, but he did extremely well. We were never worried about any market. We were very confident, even about the ones he had never visited before. I know there’s going to be growth and opportunity moving forward in Asia. He held a festival there last year, so I think that’s going to be another great market for him.

Rauw: I would love to conquer Asia with my music; it’s one of my goals. I’ve been to Japan many times and performed there for the first time last year. It’s totally different performing for them. Japanese people are really organized. It’s not like us Latinos that are loud and crazy. Setting a new goal is what always keeps me going and gives me energy to continue working and craft my art.

Alejandro backstage on the opening night of the Cosa Nuestra tour at Climate Pledge Arena on April 5 in Seattle.

Marco Perretta

Hans Schafer, senior vp of global touring, Live Nation: When you talk about global benchmarks, Rauw’s position competes on the same level as top global pop acts, not just within Latin music. When we talk about his place in the industry and what this tour has accomplished, it’s as high up with any of the other global acts, regardless of genre.

Mike G: He’s a cultural icon and he’s growing outside of his core genre. The unique thing about Rauw — and what separated him from a lot of artists in certain key markets — is that he can do 50,000-plus tickets.

Schafer: When we look at some of the tours internationally that we’ve been doing, including Rauw’s European leg that we did in the summer, you see the diverse markets and that those fans are there. Those fans are crossing over, even more so than what we’ve seen in the past.

Mike G: When you think about Rauw, he is in the conversation. His work ethic, high energy; he’s physically dynamic, he’s got a strong stage presence. He has that crossover appeal; he has a loyal fan base. The demand is big, it’s major. If he wanted to do stadiums next year, he could do it, but he needs to take a vacation first. He needs to put his phone down, rest, and when he’s ready, we can plan accordingly. He has that luxury.

Rauw: I haven’t taken a break since I started touring this year. I began working on this tour after my birthday [Jan. 10] and continued working until today. My next vacation is going to be Christmas. After the holidays, I’m probably going to disappear for a while, but meanwhile, I’m already with a small notebook and taking notes for my next chapter.

This story appears in the Oct. 25, 2025, issue of Billboard.

Trending on Billboard On a late-spring night, Downtown Miami was a place out of time. Thousands of people gathered dressed to the nines, the women rocking sequined gowns and kitten heels, the men wearing tailored suits and polished dress shoes. Their attire fused Puerto Rican culture and Mafia fantasy and seemed beamed in from decades […]

Nearly a decade before contemporary Christian music (CCM) star Brandon Lake was headlining arenas, topping Billboard’s Christian Airplay charts and winning Grammy Awards, he was a young church worship leader in Charleston, S.C., who just wanted to record an album — and took an unorthodox route to making that happen.

“I did a GoFundMe campaign. I said, ‘If you pledge a certain amount, I’ll tattoo your name on my leg,’ ” explains Lake, 34, as he sits across from me onstage in the sanctuary of Seacoast Church, the Charleston megachurch where he began leading worship as a teenager. He taps his left leg: “So I have 22 last names of folks who donated tattooed on my thigh.”

In 2016, he released the result of that campaign, Closer — and since then, his songwriting skill; gritty, full-throttle vocals; and willingness to address sensitive topics like anxiety and mental health in his music have made him one of the biggest stars in the CCM world. He has released four more albums and dominated Billboard’s Christian music charts, landing 43 entries on Hot Christian Songs, including 2023’s 31-week No. 1 “Praise,” recorded with the collective Elevation Worship.

But though he remains deeply committed to the Christian market, Lake is also looking beyond it. He recently earned his first crossover hit, making his Billboard Hot 100 debut in November 2024 when the raw, soulful “Hard Fought Hallelujah” bowed at No. 51. In February, he teamed with country hit-maker and fellow ink aficionado Jelly Roll for a collaborative version of the song.

“I just wanted to share this with somebody who really gets this story, who’s lived it,” he says of recording the song about hardship-tested faith with Jelly Roll. “Now to see him carrying this song and how we carry it together and it’s impacting so many lives — that’s the goal.” He adds, “We’re in a perfect time for this kind of collaboration to happen… The truth is, all of us are just as messed up — it’s just some of us are good at hiding it and putting a mask on. Everyone’s on a journey.”

Brandon Lake photographed May 22, 2025 in Charleston, S.C.

Will Crooks

Lake’s Hot 100 debut comes as CCM is having a major moment on the all-genre chart. “Hard Fought Hallelujah” and Forrest Frank’s “Your Way’s Better” appeared simultaneously on the chart this year — the first time in more than a decade that two CCM songs were on the Hot 100 at the same time. The last time a non-holiday song recorded by a primarily CCM artist reached the Hot 100 was Lauren Daigle’s “You Say,” in 2019.

Those breakthroughs occurred amid an overall rise in consumption of CCM over the past 18 months. According to Luminate, in the first half of 2024, sales of track-equivalent albums, streaming-equivalent albums and on-demand audio for the genre grew 8.9%, with CCM ranking as the fourth-fastest-growing musical genre after pop, Latin and country. The music’s broadening sounds, as well as increased collaborations between CCM and secular artists over the past several years, have helped CCM songs become more heavily integrated into mainstream playlists: Spotify has noted that during the past five years, CCM experienced a 60% growth rate globally and a 50% growth rate in the United States on its platform, as artists previously confined to the genre started to penetrate mainstream spaces.

That strong upward trajectory owes in large part to a new generation of CCM artists such as Lake, Frank, Josiah Queen and Seph Schlueter. They relish crossing genre lines: Frank’s music, for instance, is more rooted in pop and hip-hop, while Lake’s songs anchor worship lyrics aimed at church congregations in a range of sounds including rock, blues and country. And they are also digital natives who have been intentional in harnessing the power of social media and streaming to widen the genre’s audience; a viral TikTok dance clip, for instance, gave Frank’s “Your Way’s Better” a major streaming boost.

Lake was among Luminate’s top five CCM artists in the first half of 2024, and his star has only risen since then. During his appearances at CMA Fest, held June 5-8, a social media clip of him and Jelly Roll performing “Hard Fought Hallelujah” earned over 1 million views, while a clip of the audience singing Lake’s hit “Gratitude” a cappella during a separate CMA Fest appearance earned more than 3 million views in just over 48 hours. The success of “Hard Fought Hallelujah,” in particular, has put Lake — and his faith-centered message — before broader and more mainstream audiences than he ever dreamed of: performing on American Idol, joining Jelly Roll onstage at Stagecoach in front of 75,000 fans, playing the Grand Ole Opry and CMA Fest.

From the start, collaboration has been key to Lake’s success. Closer was circulated in church and worship music circles, leading him to some of his first songwriting connections, like Tasha Cobbs Leonard, Nate Moore and Maverick City Music co-founder Tony Brown, with whom he co-wrote Cobbs Leonard’s Grammy-nominated 2019 song “This Is a Move.” Other early co-writes included team-ups with worship music collectives Maverick City Music, Bethel Music and Elevation Worship; all helped Lake expand his sound. Alongside more traditional-sounding worship anthems, his 2021 album, House of Miracles, included the soulful rock song “I Need a Ghost.”

Later that year, Elevation Worship’s “Graves Into Gardens,” co-written by and featuring Lake, topped the Christian Airplay chart and was certified platinum by the RIAA. “That’s when the floodgates opened,” he recalls. “I was getting calls from everywhere, asking me to do a concert or do collaborations — I can’t even remember how many collabs I’ve done, songs I’ve written with other people that were like, ‘Let’s just do it together.’ ” At the time, Lake notes, he didn’t even have a manager. (Since 2021, he has been with prominent CCM management company Breit Group.) “I literally kept all of my dates I said yes to in my Notes app,” Lake explains. “My manager now has that framed, I think, because of how much we’ve grown. I learned so much being around so many of my heroes.”

In 2023, Lake cemented his solo hit-maker status when “Gratitude” topped Hot Christian Songs for 28 weeks. Since, he has continued notching solo and collaborative hits, including “Fear Is Not My Future” with Maverick City Music and “Love of God” with Phil Wickham. (He’ll tour arenas and stadiums with the latter this summer.) And on June 13, he released his fifth studio album, King of Hearts, on Provident Entertainment.

Sonically, the album finds Lake deepening his exploration of diverse genres, including country (“Daddy’s DNA,” “Spare Change”), gospel (“I Know a Name,” with luminary CeCe Winans) and hard rock (“Sevens”), and features additional collaborations with writer-producer Hank Bentley and Christian rapper Hulvey, among others.

And amid the run-up to releasing King of Hearts, Lake launched another major project. In early 2025, CCM supergroup Sons of Sunday debuted, featuring Lake alongside Moore, Steven Furtick, Pat Barrett, Chris Brown and Leeland Mooring. The group has already notched four entries on Hot Christian Songs, and its self-titled debut album bowed at No. 3 on the Top Christian Albums chart upon its release in May.

“My favorite things I’ve ever created were created in community, so I think that’ll be a huge piece of my future,” Lake says. “I’ll roll with anybody who wants to go after the same things, who has the same values as me.”

Brandon Lake photographed May 22, 2025 at Seacoast Church in Mount Pleasant, S.C.

Will Crooks

As his star rises, he has stayed close to his South Carolina roots. Instead of moving to Nashville, the epicenter of the CCM industry, Lake lives with his wife, Brittany; their three sons; and a menagerie including cows, mini-donkeys and two dogs on a sprawling rural property just outside Charleston. Much of King of Hearts was recorded in a three-room Charleston studio owned by Lake’s longtime collaborator, producer-writer Micah Nichols. And even when he’s on the road, Lake makes a point of staying connected to his hometown: In 2022, he concluded the first leg of his first headlining tour with two sold-out shows at Seacoast Church; next May, he’ll wrap his 48-city King of Hearts tour at Charleston’s 12,000-seat Credit One Stadium.

But regardless of venue size or location, Lake’s goal remains the same. “When we go out on tour and it’s this huge production, huge lights and sound, I’m not doing anything other than just having church — just maybe a few more lights in cool moments,” he says with a chuckle. “It’s entertaining, but really, I want [concertgoers] to be able to say, ‘I went to the King of Hearts tour, and my life has forever changed.’ ”

What do you recall about your first time performing?