superfans

To draw his K-pop fan army onto the new OpenWav app, pop singer Kevin Woo schooled his nearly 4.4 million social-media followers on how it works. Then he sold stuff to them: $10,000 worth of hoodies and water bottles and $1,200 worth of tickets to a Los Angeles listening party in March for his single “Deja Vu.”

“It’s very refreshing,” says Woo, formerly of hit boy band U-KISS. “It gives me so much freedom to do what I want and not have to stress about ‘Where am I going to get my next paycheck? How do I know when the label’s going to pay me out?’”

OpenWav, co-created by tech entrepreneur Jaeson Ma, who co-founded influential label 88rising and was an early investor in what became TikTok, launches Wednesday (June 11) with a splashy Indie Music Week party in New York attended by Ma and artist/OpenWav executive Wyclef Jean. It’s one of many platforms designed to help indie artists reach their most devoted followers and participate in a superfan market that Goldman Sachs predicted could reach $4 billion over the next five years. The app joins a crowded market that includes SoundCloud’s “fan-powered royalty” system and a long-promised Warner Music Group (WMG) app that launched a test version starring Ed Sheeran in April.

Trending on Billboard

Ma’s invention, which has drawn $30 million from investors such as WMG and CAA’s Connect Ventures, has an all-in-one smartphone interface that allows artists to stream new songs and videos, sell tickets and quickly design (through the use of AI tools), sell and ship merch. Ma spent two years setting up an international network of 200 factories that accommodate orders of any size. “I can put my design on a premium hoodie that’s like Yeezy off-white level, and if one fan buys that hoodie, we will make it and ship it to their doorstep directly — with zero inventory,” Ma says. “It’s pretty crazy what we’ve been able to do.”

“I call this the Gen-Z Sears catalog,” Ma says on a Zoom as he scrolls through the custom golf balls, water bottles and other products available through the app. “I don’t want to say we’re faster than Amazon or Alibaba — we’re not faster. We’ve built a similar supply-chain ecosystem and made it specifically to be on-demand for artists and creators.”

In a music business where few artists can make a living from streaming revenue alone, and must tour, sell merch and develop sizable loyal fanbases to buy their products, “superfan” has become a gold-rush buzzword. (OpenWav fits this category even though Ma avoids using the term “superfan app.”) In March, Australian producer Alan Walker launched an app designed to interact more directly with fans than he could on Instagram or TikTok; Boston metal band Ice Nine Kills’ app, Psychos Only, offers exclusive merch and exclusive ticket pre-sales with a $7 monthly membership fee.

“This started out several years ago with Patreon, and we learned that for premium content, fans will pay if you create something valuable,” says Dan Tsurif, vp of digital marketing for 10th Street Entertainment, Ice Nine Kills’ management company.

Ma’s bet for OpenWav is that dedicated fans will pay $10 a month — “a Starbucks coffee,” he says — and 1,000 of them will provide each participating artist with $120,000 in annual salary. But some in the music business wonder whether such artist-to-fan tools will be relevant for a broad range of artists. K-pop stars like Woo benefit from a loyal fanbase built meticulously over years of savvy music-company marketing, and veteran touring stars from Taylor Swift to Umphrey’s McGee have spent decades building fanbases on the road, but everyone else may struggle on this kind of app.

“In K-pop, they’re already obsessive about collecting things and buying merch. With a touring artist, they’re used to buying VIP [tickets] or merch,” says Aidan Schechter, a partner at management and publishing company 1916 Enterprises and founder/CEO of management music-tools venture Patchbay. “I don’t think artists and artist teams are able to keep up with the demands of consistent posting and exclusive content creation on a lot of these apps. Artists and their teams don’t have enough stamina.”

For Woo, 33, who came up in the South Korean K-pop industry, OpenWav is a crucial tool for remaining independent. The app, which he has been beta-testing most of this year, pays 80% of merch and ticket sales to the artist and keeps 20%. Woo says OpenWav allows him access to all his sales data and analytics — he has used it, for example, to discern that he has a surprisingly large listener base in Austin, Texas, leading him to a recent South by Southwest showcase.

“I’ve been in a K-pop boy band for over a decade, and knowing how the whole system worked, I wanted to start my own venture,” he says. “As I started to learn more about the app, I fell in love with how easy and seamless it was. It’s like TikTok meets Spotify.”

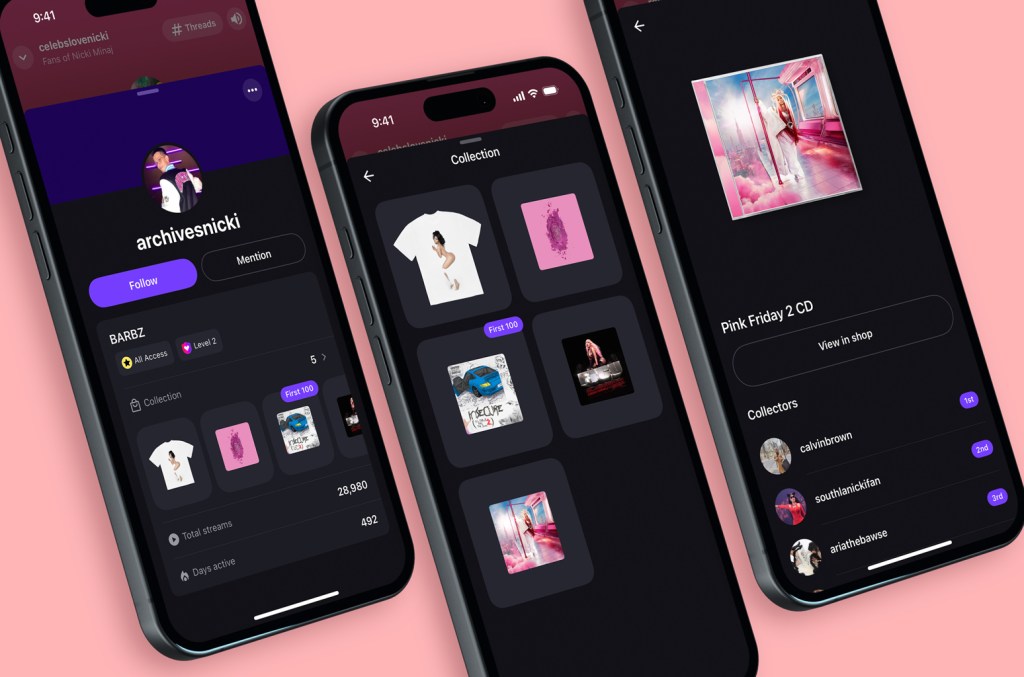

Stationhead announced the launch of a new feature on Wednesday (May 28): Collections, which allows users to show off the physical and digital merchandise that they have bought through the fandom platform.

“We were inspired by what fans were already doing,” Ryan Star, founder and CEO of Stationhead, said in a statement. “They would post receipts to prove they were there first — that they didn’t just show up late to the party. We wanted to honor that devotion and make it more fun, meaningful, and permanent.”

Stationhead debuted in 2017 as an app that allowed Spotify subscribers to transform their playlists into personalized radio stations. “It turns everybody into a DJ, basically,” Troy Carter said at the time. “You can play music, you can go live, there’s a great flow and people are commenting — it’s almost as if you took Facebook Live and layered it onto the platform.” When the civilian-turned-DJ played music, every listener also streamed it on their Spotify account, so the streams counted towards the charts.

Trending on Billboard

In January 2023, the platform added “channels,” rooms dedicated to the fanbases of specific artists. A year later, when “superfan” became the buzzword of choice for the major labels, Stationhead was well positioned to take advantage of additional interest.

The company says it now has 20 million users, and half of them are between 18 and 25. It makes money primarily from taking a portion of downloads that are sold through the platform.

The rollout of Collections follows close on the heels of another new initiative, Stationhead Shop, which launched in March, allowing artists to sell their merch on the platform through an integration with Shopify.

The goal of Stationhead Shop, Star explained, was twofold: To “combine the excitement of the merch booth with the scale and social currency of a gaming platform,” while also providing artists with another way “to monetize and build direct relationships with their most passionate and loyal fans.”

After fans buy something, they now have the ability to flaunt their purchase. “In a world where your online identity matters, this is how fandom shows up,” Star added. “If Roblox and Fortnite taught a generation to express themselves through virtual skins and items, we see Stationhead Collections becoming that for music.”

Interest in superfans and their revenue potential has become so strong that market research firms and equity analysts are digging into the topic. This week, Bernstein released a report on music streaming services’ potential moves and MIDiA Research released a new report about music streaming pricing strategy.

For the uninitiated, a music superfan has been defined by Luminate as those fans who interact with artists and their content in multiple ways, including streaming, social media, physical music purchases and buying merchandise. These superfans make up 19% of U.S. music listeners, according to Luminate, and are more likely than the average fan to buy physical music, spend more on music, discover new music, connect with artists on a personal level and participate in fan communities.

Efforts are well underway to tap into superfans. Labels and artists employ e-commerce to sell merchandise, LPs and CDs directly to consumers, circumventing traditional retail channels and building a direct billing relationship with the most valuable fans. Startups such as EVEN and Fave — Sony Music and Warner Music Group are investors in the latter — are focused on connecting artists with their most fervent supporters. Given the multi-billion-dollar size of the music streaming market, though, Spotify’s plan to launch a superfan tier could be the most impactful play.

Trending on Billboard

Bernstein’s “Superfan Economics 101” report argues that a super-premium tier will help music streaming platforms achieve “sustained success in an increasingly competitive environment.” Analyst Annick Maas sees superfan-focused products as a function of the shift from mass consumption to direct-to-consumer tactics. Reaching out to smaller subsets of a larger audience, he writes, allows a streaming platform to “create a sense of belonging for its subscribers” and increase loyalty and engagement. That an equity analyst would highlight superfans in a report to investors speaks to the revenue potential in targeting subsets of consumers and the likelihood that publicly traded companies will make superfans a larger priority.

MIDiA Research also added to the superfan knowledge base this week by releasing a report based on a survey of 2,000 U.S. consumers. The main takeaway is that MIDiA found widespread interest in paying a higher price for a streaming service with additional features: Just under three-quarters of people surveyed have “some level of interest” in paying for a super-premium tier as an add-on to the basic subscription plan.

Exactly what people are willing to pay varies greatly, though: 22% of respondents are willing to pay an additional $1.99 per month fee while 10% are willing to pay an additional $13.99, more than double the current $11.99 price for an individual subscription.

To give an idea of the amount of revenue at stake, consider that there was an average of 100 million subscribers of subscription music services in the U.S. in 2024 who paid an average of $8.91 per month, according to the RIAA. (That figure does not include limited-tier subscriptions such as ad-free internet radio.) Those 100 million subscribers generated $10.69 billion over the year, which works out to $106.87 per subscriber per year.

If 10% of those 100 million subscribers — which include student and family plans in addition to standard individual plans — paid more than double the current price, total revenue would increase 10.8% to $11.76 billion, equal to $117.56 per subscriber annually or $9.80 per month. The 10.8% revenue growth is equal to $1.15 billion of incremental royalties.

The RIAA’s average revenue per user (ARPU) of $8.91 for 2024 is lower than the $11.99/$12.99 price being charged for the most popular individual plans, suggesting the 100 million subscribers figure includes many student and family plans. So, to measure the effect of the price increase on the RIAA’s ARPU, I multiplied ARPU by the ratio of the super-premium individual plan ($12.99 + $13.99) to a standard individual plan ($12.99).

So, without an increase in the number of subscribers or a price hike, doubling the fee for a tenth of subscribers would deliver a 10.8% revenue boost. Not all of those consumers would jump to the super-premium tier at once, however, meaning a double-digit increase in subscription revenue would accrue gradually over multiple years.

Charging an additional $1.99 super-premium fee on top of a standard subscription price would result in an incremental $334 million. Total revenue would increase 3.1% to $11.02 billion and ARPU would rise from $8.91 to $9.18.

Another option to expand the subscription base is a low-priced, “subscription-light” tier that incorporates advertising into paid subscriptions. Music streaming subscriptions have kept advertising out of their paid products, but there have been suggestions — namely from Goldman Sachs analysts who prepare the influential Music in the Air report — that a subscription-light tier that includes ads could help expand the subscription market.

Paid video subscriptions used to be a respite from the advertising world, but advertising has become well established on video platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime and Hulu. Amazon Prime now inserts ads in movies, and Netflix and Hulu offer a low-cost, ad-supported option to make their products palatable for more price-conscious consumers.

But MIDiA’s survey suggests a subscription-light option is unpopular. About three-quarters of respondents who aren’t currently subscribed to a music streaming service aren’t interested in starting. This sizeable group of consumers doesn’t listen to music often enough to pay, or they find the current prices too high. Excluding the 100 million U.S. subscribers, there are approximately 188 million Americans aged 13 or older who do not subscribe to a streaming service (there are 51.9 million people under 13). Based on MIDiA’s findings, roughly 141 million of them aren’t interested in paying for a subscription. For them, there’s also YouTube and ad-supported radio.

What’s more, a subscription-light offering could be problematic. MIDiA found that ad-supported paid streaming attracted interest only “at very low price points” and warned it could harm overall subscription revenues by cannibalizing normal subscription tiers. With paid subscriptions currently creating the majority of U.S. recorded music revenue, and with subscription growth playing a prime role in Wall Street’s expectations for music companies, both platforms and labels may be unwilling to put that revenue at risk by offering a less expensive choice to millions of consumers who may soon be looking for ways to tighten their belts.

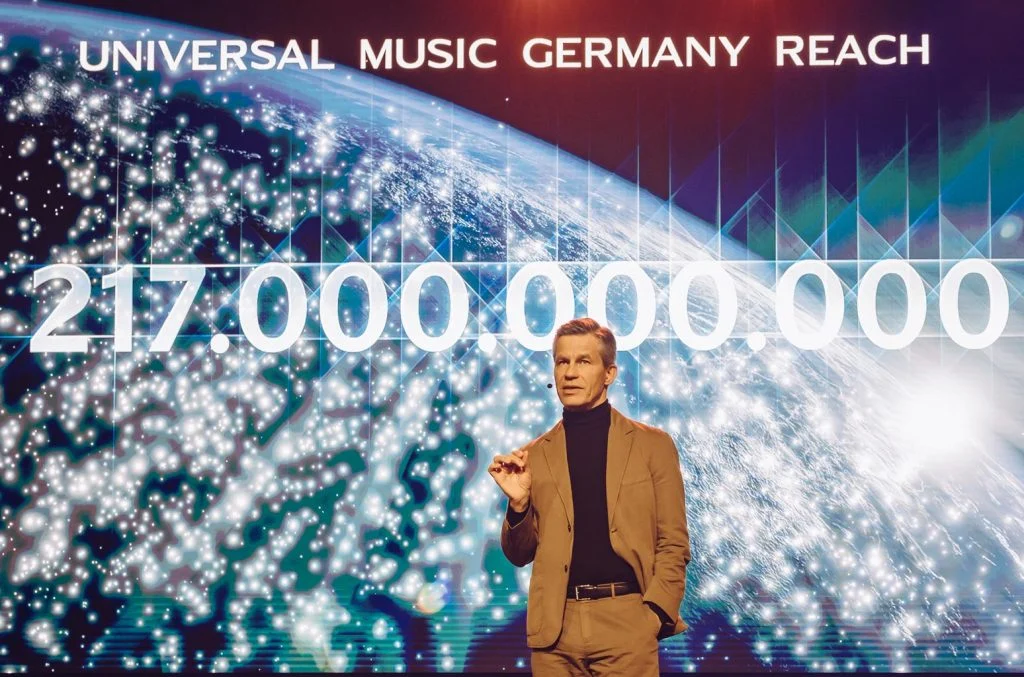

At Universal Inside, held Wednesday (March 26) at the Tempodrom in Berlin, UMG Central Europe chairman/CEO Frank Briegmann showcased some of the label’s acts, updated attendees on the state of the German music market and offered a glimpse into the company’s future.

After an appearance by the pop act Blumengarten, Briegmann shared some good news about the German business. As streaming growth slows in other regions, Germany still has plenty of headroom, which is why the market grew 7.8% in 2024, surpassing the 2 billion euro mark for the first time. He also made the point that this was good news for artists, who one study showed increased their collective revenue faster than labels between 2010 and 2022.

Briegmann also laid out a plan for growth that relies on UMG’s “artist-centric model” to increase payments to acts that meet certain criteria, as well as the “streaming 2.0” idea that is intended to induce superfans into paying more for subscriptions. The label had an impressive 2024, accounting for five of the year’s top 10 albums, including Taylor Swift and Billie Eilish releases in the top two spots. Briegmann also pointed to the success of UMG’s classical label Deutsche Grammophon, where he is also chairman/CEO, as a particular highlight.

Trending on Billboard

Much of the potential for growth lies in superfans, Briegmann said, and pointed to the history of UMG’s efforts to identify, track and reach them directly. The latest iteration of that is a new in-house direct-to-consumer operation, SPARKD, which will offer artists a new service to reach consumers with both albums and merchandise sold by UMG’s Bravado, which will be integrated into the label business in Germany. Bravado will continue to do business with both UMG artists and others. The idea is to use existing data to drive more different kinds of business — which would, in turn, generate more data. Already, Briegmann said, Bravado had grown its German merchandise revenue by 50% in the last three years, thanks in large part to its direct-to-consumer business.

Universal Inside is never all business, and as usual, Briegmann introduced some of the label’s artists. He briefly interviewed German pop star Sarah Connor, who spent much of her career singing in English but will soon release the final album of a German-language album trilogy, Freigeistin. Deutsche Grammophon president Clemens Trautmann introduced the label’s star pianist Vikingur Ólafsson, and Gigi Perez played two songs on acoustic guitar.

The event closed with a brief speech from Berlin Senator for Culture and Social Cohesion Joe Chialo about the significance of the Electrola label, after which the German act Roy Bianco & Die Abbrunzati Boys played a few songs, joined for the classic “Ti Amo” by the schlager icon Howard Carpendale.

Get ready for a new era of innovation by streaming services. That was the message sent by Universal Music Group (UMG) chief digital officer Michael Nash during the company’s fourth quarter earnings call on Thursday (March 6), during which he noted that the label is currently in talks with all of its streaming partners — not just Spotify — about super-premium tiers.

“There’s a continuing wave of innovation that we’ve seen really transform our business and transform the digital landscape in particular, over the last decade, and we anticipate that that’s going to continue as the market grows,” said Nash.

Not that streaming services haven’t been innovating since day one. Listeners have enjoyed new ways to discover music (the growth of playlists, personalized listening and algorithm-driven radio stations), follow their favorite artists (album pre-saves) and view concert listings and lyrics. From 2011 to 2014, Spotify allowed developers (Rolling Stone, Billboard, Tunewiki and Songkick, among others) to build apps that lived inside its platform and utilized its song catalog. Services such as Tidal and Qobuz have made high-fidelity audio a part of their brand identities. And over the years, the types of subscription offerings expanded from individual plans to encompass family plans and affordable student options.

Trending on Billboard

But the type of innovation that Nash referenced is different. Except for high-fidelity audio, streaming innovations haven’t resulted in greater revenue per user — all the features packed into streaming services haven’t cost the consumers anything extra. That’s going to change. The next wave of music streaming will have products and services that carry higher prices. After decades of providing the same service to all customers, streaming platforms will segment the market and offer premium products to a subset of their subscribers.

Super-premium streaming is one component of what UMG calls “streaming 2.0.” On Thursday, CEO Lucian Grainge explained that streaming 2.0 “will build on the enormous scale we’ve achieved thus far in streaming’s initial stage. This next stage of streaming will see it evolve into a more sustainable and growing, artist centric ecosystem that improves monetization and delivers great experiences for fans.” Offering multiple tiers rather than a single subscription plan, Grainge said, “enabl[es] us to segment and capture customer value at higher than ever levels.”

Conversations about superfan offerings have extended as far as concert promotion and ticketing. Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino revealed during the company’s fourth-quarter earnings call that streaming services are interested in pre-sale ticket offers. “We’ve talked to them all about ideas on if they wanted inventory,” he revealed on the Feb. 20 call. “There’s a cost to that, and we would entertain and look at that option if it made sense for us in comparison to other options we have for that pre sell.”

Spotify is known to be working on a superfan product — CEO Daniel Ek revealed in February that he is testing an early version — but Nash suggested other streaming services could follow suit. “We’re in conversations with all of our partners about super-premium tiers,” he said. “We think this is going to be an important development for segmentation of the market.”

JP Morgan believes the customer segmentation that Nash referenced will be a component of UMG’s growth over the next 10 to 20 years. “In a streaming 1.0 world UMG was reliant on DSPs raising retail price rises if it was to benefit from a higher wholesale price; in a streaming 2.0 environment UMG has visibility on wholesale price rises that underpin its growth algorithm, while still having potential upside should DSPs raise prices above the minimum,” analysts wrote in a March 6 investor note.

UMG’s market research suggests that 20% of music subscribers are likely to pay for a superfan streaming product, according to Nash. If Spotify reaches that threshold, it will have converted roughly 53 million of its 263 million subscribers into higher-paying customers (as of Dec. 31). It’s already worked for at least one company outside the U.S., as Tencent Music Entertainment has already proven there’s demand for a high-priced, value-added streaming product: Its Super VIP tier, which costs five times the normal subscription rate, had 10 million subscribers at the end of September — over 8% of TME’s 119 million total subscribers. If other streamers can successfully follow suit, new superfan streaming products will generate more revenue for artists, rights owners and streaming platforms — and help the music business continue to grow for years to come.

For two decades, the price of a music streaming service was frozen at $9.99 per month. Prices only began rising in 2022, leading to improved economics for both streaming companies and rights holders. Now, streaming platforms are closer to taking another leap forward in monetization.

The next phase of the music business, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek said during the company’s earnings call on Wednesday (Feb. 5), is tailoring experiences to “different subgroups” such as lucrative superfans. In fact, Spotify has already developed something for these subscribers, and Ek is currently testing the unnamed product. “I’m personally super excited about this one, and this is a product I’ve been waiting on for quite some time as a super fan of music,” he said. “And I’m playing around with it now, and it’s really exciting.”

Targeting superfans is part of Spotify’s current focus on launching new products. Ek called 2025 “the year of accelerated execution,” meaning the company “can pick up the pace dramatically when it comes to our product velocity.” Exactly how these new products will be monetized and ultimately impact artists and rights holders is unknown. But Alex Norström, Spotify’s co-president/chief business officer, hinted at both higher price points and an a la carte approach when he told analysts that “future tiering” and “selling add-ons to our existing subscribers” are two of the ways Spotify thinks about increasing average revenue per user.

Trending on Billboard

Recently updated licensing agreements with Universal Music Group (UMG) and Warner Music Group (WMG) also hint at the pending arrival of superfan products and additional pricing tiers. In announcing renewed deals with Spotify, both UMG and WMG cited their agreements’ ability to enable new paid subscription tiers and exclusive content bundles.

Sony Music and independent distributors and publishers have not announced a similar renewed agreement, however, and new licensing agreements with all of them would be necessary for the kind of product Spotify has described, says Vickie Nauman of digital music advisory and consultancy CrossBorderWorks. “If there is a superfan layer that is built around sound recordings, then it’s going to require licensing with revenue share between platform, publishers, labels and PROs,” she says.

Exactly what Spotify’s superfan product will look like and require from artists remains to be seen. Nauman hopes Spotify will learn from past mistakes. “I’m not sure what the killer features for a superfan might look like, but whether niche apps or DSPs, this cannot require the artist to do much if anything,” she says. “We have a long history of failure of initiatives requiring artists to post on social, port their fans to a new app and deliver custom content, and this simply doesn’t work. Artists want to be artists.”

New licensing deals also open the way for a more expensive, high-resolution audio tier which Spotify first began teasing in 2021. “Of course, the success of launching with a limited content pool depends on what’s on offer with the new service, but there’s not a big downside to launching a new service that has limited hi-res music, where the selection of music is highly likely to increase over time,” says digital music veteran Dick Huey of consultancy Toolshed. “I doubt that adding hi-res music to Spotify will be particularly controversial, in particular because they’ll bring an upsell to labels, that of higher subscription costs. Also, because other services already offer hi-res music.”

Whatever the final product, streaming services’ targeting of superfans — if history is any precedent, competitors will follow Spotify’s lead — will produce incremental revenue for Spotify and more royalties for creators and rights owners. The new additions could also help reduce artists and songwriters’ frustrations about the economics of streaming music that have plagued Spotify. As for subscribers who opt into the new offerings, they’ll get more features and artist access in return for higher fees. In short, these new iterations of Spotify should create a win-win-win for all parties in the equation.

Artists such as Ariana Grande, Dua Lipa, Megan Thee Stallion and Conan Gray helped Weverse, HYBE’s social media/fandom platform, grow its users by 16% in both the U.S. and Canada in 2024, the company announced Wednesday (Jan. 22). Weverse users also saw strong growth elsewhere, rising 21% in Brazil, 14% in Mexico, 22% in Japan and 54% in Taiwan. Originally a platform for K-pop groups, the platform has grown along with HYBE’s global expansion and posted 19% user growth across all territories.

Those statistics and more come from the new 2024 Weverse Fandom Trend Report, a recap of the platform’s tremendous growth and a testament to fans’ interest in their favorite artists. Joon Choi, president of Weverse Company, called 2024 “a transformative year” that expanded the platform’s artist communities, fan engagement and commerce activities. “Weverse remains committed to innovating its services to meet the evolving needs of artists and fans, solidifying its position as the center of global fandom culture,” he said in a statement.

Trending on Billboard

As much of the music industry begins to focus on better serving superfans, Weverse has already established itself as a money-making destination for fans of a select group of artists. The platform launched in 2019 and last year introduced a subscription tier that provides ad-free viewing, video downloads for offline access, high-quality streaming and language translation. “Digital membership, we believe, is the very first cornerstone of the future evolution [of Weverse],” Choi told Billboard in December.

Like a typical social network, Weverse allows artists to publish messages and content and gives fans an opportunity to leave comments. In 2024, Weverse Artists on the Weverse platform shared approximately 206,000 posts and fans generated 370 million posts. SEVENTEEN had the highest number of posts while ENHYPEN had the most comments. The platform also allows fans to send direct messages to artists — a perk for subscribers. Last year, artists sent 698,000 direct messages to fans and fans sent 96.36 million messages to artists. More than half (55%) of artists on Weverse send direct messages to fans at least every two days. Fans also sent 4.88 million personally decorated digital letters. Jung Kook received the most fan letters while LEEHAN of BOYNEXTDOOR responded to the most fan letters.

Weverse also hosted 5,787 live broadcasts on Weverse Live, the platform’s live streaming feature, totaling 4,779 hours of content in 2024 (artists don’t only live stream concert performances on Weverse Live and in fact usually opt for casual interactions and Q&A sessions with fans). Weverse Live videos were viewed 426 million times by 11.25 million unique Weverse users in 2024, while the top live stream of the year was “Missed You a Lot” by Jung Kook, which amassed 23 million real-time views.

E-commerce separates Weverse from a typical social network. Through Weverse Shop, Weverse sold 20.6 million pieces, a 13% increase from 2023. Physical merchandise such as albums and collectibles improved 10%, while Weverse Shop also sold 3.4 million pieces of digital merchandise, including artist memberships and online content, a 24% increase. Other than Weverse’s home market of South Korea, the United States and Japan were the top markets for merchandise. The top-selling digital items were artist memberships: BTS ARMY memberships were most popular in Oceania, Latin America and Europe while SEVENTEEN’s CARAT memberships were most popular in North America.

For all the value derived from social media, artists and labels have yet to generate revenue directly from their activity on Facebook, Instagram and other platforms. In contrast, Weverse, a social media and e-commerce platform owned by South Korean company HYBE, changes up the typical social media dynamic by generating direct revenue from the fandom it facilitates.

This month, in an effort to generate even more revenue from superfans, Weverse introduced a digital membership tier that offers additional perks such as ad-free viewing, video downloads for offline access, high-quality streaming and language translation. The paid digital membership is separate from the fan clubs offered on the platform and Weverse’s own direct messaging feature that allows users — for a fee — to message their favorite artists.

“Digital membership, we believe, is the very first cornerstone of the future evolution” of the music business,” Weverse CEO Joon Choi tells Billboard. He adds that in the first two weeks that digital memberships were made available on the platform, 79 artists (out of 162 active artist communities on Weverse) have given fans the option of signing up for them.

Trending on Billboard

Weverse is an anomaly in social media: a platform with a small number of high-demand musicians rather than a large number of mostly unpopular artists. Launched in 2019, Weverse had 9.7 million monthly active users (MAUs) as of Sept. 30, according to HYBE’s latest financial results, down from 10.6 million a year earlier. The platform is a Swiss Army knife of a promotional vehicle. Artists not only post media content and updates but also conduct live-streams and respond — for a fee — to fans’ direct messages, while the platform additionally sells concert live streams, music and merchandise. And HYBE’s most popular artists can rack up amazing numbers on the platform: Earlier this week, BTS member Jung Kook set a Weverse record with 20.2 million real-time views of a 2.5-hour live broadcast in which he spoke to fans during a break from his military duty.

In recent months, Weverse expanded beyond K-pop artists by welcoming such Western, English-language stars as Ariana Grande and The Kid Laroi, hinting at possibilities that have record labels salivating. Goldman Sachs analysts have estimated that improved monetization of superfans — including new digital platforms, greater emphasis on vinyl buyers and higher-priced music subscription plans — could result in $3.3 billion of incremental revenue globally by 2030. Given the potential, it wasn’t surprising to hear both Warner Music Group CEO Robert Kyncl and Universal Music Group CEO Lucian Grainge express their interest in superfan products and experiences earlier this year. In September, UMG CFO Boyd Muir said the company was in “advanced talks” with Spotify about a high-priced superfan tier — something Chinese music streaming company Tencent Music Entertainment already launched with early success.

In the early days of its membership tier, Weverse is still figuring things out. “We are pioneering this field, so we see a lot of unknowns,” says Choi. For example, he says Weverse has heard from many labels that it should bundle the digital membership tier with fan clubs already offered by artists into something like a premium membership tier (of the 162 active artist communities on Weverse, 72 currently offer fan clubs). He adds that Weverse would not make the decision independently but is discussing it with labels. “Combining them together in the future, I think it’ll be stronger than what we offer right now,” says Choi.

The rollout of the membership tier hasn’t been without controversy, though. In October, an article at The Korea Herald quoted an email from Weverse to its partner record labels in which the company said participation in the membership tier is “mandatory for all artist communities hosted on Weverse.” The article also quoted a South Korean lawmaker who called on the country’s Fair Trade Commission to investigate Weverse’s “new forms of monopolistic practices and determine whether unfair treatment is occurring against affiliated companies using the platform.” Weverse says it has not been contacted or investigated by regulators.

Choi pushes back against the assertions in The Korea Herald, saying artists on the platform are not required to offer a subscription tier, in contrast with the email quoted by the newspaper. “That’s not mandatory,” he insists. In a separate statement to Billboard, Weverse said it “aims to roll out digital membership to all communities” but that the decision “is the choice of labels and artists” and, in any event, fans will still be able to use many existing Weverse services for free. Despite Weverse playing an integral role in the marketing and promotion of K-pop artists, Choi argues it doesn’t have enough market power to make such demands: “We are not in a dominant place where we can just present the policy and dictate our policy to the artist or labels however we want.”

Weverse has also received criticism for its revenue-sharing splits with labels, with The Korea Herald additionally citing an anonymous source as saying the company proposed a “disproportionate” share of the revenue ranging from 30% to 60%, leaving the artist and label with anywhere from 40% to 70%. Choi declined to comment on the business arrangements that determine how much subscription revenue Weverse keeps but noted the platform is investing money into the subscription tier to create features valuable to artists and their fans.

The pushback encountered by Weverse foreshadows the challenges platforms and labels will face as superfan platforms proliferate and the stakeholders wrangle over how the money will be shared. Labels and publishers have spent decades trying to get more value from streaming services, and short-form video apps like TikTok necessitated new conversations about how to compensate creators for the value they bring to the platform. As Choi says, “What we’re doing is basically creating a new value by connecting the artist and super fans in the same place.” In the process, HYBE has pioneered a new model that could become standard practice for artists and labels in the music business of the future.

Andrew Batey is best known to the music industry as the founder of streaming fraud prevention company Beatdapp. But for the last six years, Batey has been simultaneously building up a venture capital firm called Side Door Ventures. “I always wanted to just be viewed as a founder, but Beatdapp is probably my last company,” says Batey, a serial entrepreneur, who has also built companies in the restaurant and digital marketing industries. “I started thinking about where I want to transition to eventually, and I believe it’s investing.”

For the last 15 years, Batey says he’s mentored hundreds of companies at different accelerators, which is where he got the itch to start stepping into the investor role. After years of angel investing to check his aptitude, he realized, “I feel like I’m really good at picking the right companies.”

Side Door quietly launched in 2018 and comprises 14 different smaller funds covering a wide array of disciplines — space travel, blockchain, manufacturing and more. Investors are also interested in music and entertainment, too, though Batey says it needs to be something he believes he can grow “by 100x” and “there are not that many” entertainment startups that fit that bill. To date, he’s made investments in companies like SpaceX, Pipe, Plaid, Varda and EtherFi, as well as music-related startups like JKBX and the now-defunct superfans app Renaissance, which he felt particularly passionate about.

Trending on Billboard

In total, Batey says Side Door has averaged 61% gross internal rate of return across all funds since its launch and has over 100 companies in its portfolio.

Now that Beatdapp has established itself as an industry leader with partnerships with Universal Music Group, the Mechanical Licensing Collective, Beatport, SoundExchange and more, Batey is ready to talk about Side Door Ventures for the first time.

Why are you making your press debut, six years into Side Door Ventures?

To talk about it too early seemed like a giant, “Look at me! Look at me!” And that’s not really what a founder needs — a founder needs help. I’ve always just felt comfortable being the neck that moves the head, but I’ve lost my ability to be stealthily leading this, the more checks we’ve written.

In the beginning, a lot of startups just thought I was a founder. As soon as we had that founder-to-founder rapport, the person would just start sharing all these things that he wouldn’t have shared with an investor. But none of them were deal breakers. I found the transparency actually really great. There was a strength in meeting a founder at their level, without them knowing you’re the investor.

I named the fund Side Door Ventures because they never saw it coming when I would meet with the founder. They just thought I was mentoring them, and then I would suddenly be like, “I’d like to write a half million dollar check.”

It really favored us well because I wasn’t convincing them why they needed our money. I gave them advice and mentorship first, and then told them I wanted to write the check and that’s the exact thing they want. Many want someone that’s going to be helpful, and not someone just writing a check. In really tight funding rounds where people get pushed out, we often got into them early on when we should never have been.

But the cat’s out of the bag, and I’m ready to just own it.

What makes Side Door Ventures different from others in the field?

Fundamentally, the way we’ve been billed as a fund is entirely different than everyone else. We intentionally started with small funds that are $10 million to $30 million each. We have 14 funds overall.

When I started the fund, I had a big family that offered to give me $100 million to get started, and they wanted to know what my strategy would be. I always felt that big funds are really hard to return. So my strategy was, Why don’t we make a bunch of smaller funds of higher return multiples that traditionally perform better?

When I started talking to fund managers, though, they thought it was crazy. They’re like, “Institutions won’t bankroll that — a pension fund wants to have a check size of at least $10 million.” If you’re building a fund to please people covering their ass, you’re not building a fund for optimal returns. And if I was building a fund for optimizing returns, and if this was my money, I would go the opposite way and make a bunch of small funds. So my customer investor is totally different than most. My customers are high net worth individuals and families who care more about the returns, and less about whether I check a box.

For every small fund we have a slightly different iteration. We have one with the state of Michigan which is just focusing on manufacturing, advanced materials and mobility — things that the state of Michigan has talent resources for. We have a web3 fund which focuses on blockchain. We have a seed fund which is focused on seed investing. We have a European fund focused on European college students, specifically. I don’t know any other funds doing it like this.

Most Billboard readers know you as the founder of Beatdapp. Given that background, do you have interest in investing in companies that are complementary to what Beatdapp does?

Because of Beatdapp, I have views on where the industry could still use a lot of help, and I probably have some unique data insights about where there’s juice to squeeze. But I view Side Door and Beatdapp as entirely separate. We don’t have any of the same investors, so I don’t take money in one entity and then bring it to the other. It’s a fully firewall situation where we have different investors, different teams, different everything.

If there is anything that I’m too privy to because of my work outside of Side Door — let’s say that I have a relationship with founders of a company — I generally sit out of the investment committee and let the rest of the committee decide so that there’s no bias going into the decision making.

I love music and entertainment. It’s a big part of my background, so I obviously want to invest in things that are in that sector. But the majority of all music companies exit for under $15 million. The reality is that music is not the best venture-backable investment, which means that there are very few companies that meet the sort of the requirements to warrant a venture capital investment from us.

We have a bunch of funds, but they’re all basically investing in things we think could [provide] 100x [returns]. So if you’re a music startup valued at $20 million, how many companies have exited that are over $2 billion? The answer is probably only a handful — like Spotify.

That means one of two things. I either have to catch you way earlier, like in your first round, or you need to be such an outlier that I believe the market will move in your direction. For example, we invested in JKBX. Why? If you think about JKBX as a trading entity and the fact that it’s more of a fintech play than it is a music play, you could see a platform getting traction. Now, will they make it or not? Only time will tell. But they have the profile to potentially be worth billions of dollars if they can build that habit formation and become another asset type.

You have mentioned before that you learned a lot from investing in a superfan company, Renaissance, which ultimately went bust. Monetizing the superfan is such a hot topic in the music business right now. What did that experience teach you about the viability of superfan-related startups?

We see 7,000-8,000 deals a year, and I cannot think of another case where I saw a consumer-facing application that was as sticky with their fans as Renaissance. They had a million downloads — all organic, no marketing. They had 47% day-90 retention, meaning 47% of all users stuck with it after 90 days, which is insanely good. I think the average user launched the app 21 times per day — that’s like Instagram level.

The problem is that I don’t think they knew how to fully monetize it. Artists didn’t want to pay for it, labels didn’t want to pay for it. There wasn’t a big enough venture-backable business there. It was more of a $10 million to $15 million business, but how do you make that a $100 million business? They were struggling to figure out what could be scaled.

If this company who had the viral, organic growth and absolutely crushed it couldn’t figure out how to get those customers to pay, and couldn’t figure out how to get artists to pay, and couldn’t figure out how to get labels to pay, then how are any of these other fan apps going to make money?

The only way I think you can build a successful “superfan” business is by owning the merch pipeline itself — basically, you need to be the one that’s vertically integrated. You need to be integrating and selling the actual goods yourself so that you can build enough margins in there to support the business. If you were just a third party marketplace for all these other goods and services — like posters and tickets and merch — I don’t think there’s enough money there. I don’t believe that’s scalable.

This summer, the major labels filed a lawsuit against two AI music startups, Suno and Udio, and in early September, it was revealed that the use of AI music was instrumental in the scam alleged in the $10 million streaming fraud lawsuit. Do you see this affecting people’s confidence in AI music startups?

It could affect consumer confidence, but I do not think it will dissuade investors. The reality is, investors aren’t afraid of breaking things. Where a lot of people are mad because the status quo is changing, a lot of investors see that as a positive — as they say, “Volatility breeds profitability.”

However, what will succeed here is whoever comes up with a business model where everyone wins and it’s convenient for consumers, and they enjoy the experience. I haven’t seen one that wins yet. I haven’t seen a business model where consumers actually like it.

Look at the Drake–Weeknd guy [anonymous TikTok user Ghostwriter and his song “Heart On My Sleeve,” which used AI to deepfake Drake and the Weeknd]. His song was listened to millions of times, but it also had a pretty equal number of listeners. What that means is people were only listening to it one time or so and then leaving. It was a novelty. It wasn’t something that people saw longterm value in. Until there’s a product that people see longterm value, it’s not going to work.

Universal Music Group and Spotify are in “advanced talks” over a high-priced, superfan tier of the streaming service that offers a better user experience than the standard subscription plan. The status of the negotiations were revealed by UMG CFO Boyd Muir on Tuesday during the company’s Capital Markets Day presentation in London. That a Spotify […]

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio