Live nation

Page: 3

Investors seeking shelter from the chaos unleashed by President Trump’s often incoherent tariff policy can find safety in companies without direct exposure to tariffs or the teetering advertising market. And music, especially digital music, will be able to weather the storm, say many analysts — with one major exception.

To understand what people are thinking about tariffs’ impact on the business world, look no further than stock prices. The performance of various music-related stocks reveals how investors are betting that economic uncertainty will affect various companies.

Many stocks — especially those of companies traded on U.S. exchanges — have taken a hit as investors fled for safer alternatives. The Nasdaq and S&P 500, U.S. indexes, are down 6.2% and 6.7%, respectively, since April 1, the day before President Trump announced his tariff plans. Elsewhere in the world, indexes have generally performed better. South Korea’s KOSPI is down just 2.0%. Japan’s Nikkei 225 is off 3.5%. The U.K.’s FTSE 100 is down 4.2%. Germany’s DAX has lost 5.9%.

Trending on Billboard

Within music, companies that get most of their revenue from streaming are faring relatively well. Since April 1, Spotify and Deezer have each gained 4.0%, two of the better showings for music stocks. Cloud Music improved 3.9%. Tencent Music Entertainment, on the other hand, has fallen 15.1%, although its share price remains up 8.1% year to date.

Record labels and publishers have also been holding up well, in relative terms, particularly outside the U.S. Since April 1, shares of Universal Music Group (UMG) — which is headquartered in the U.S. but trades in Amsterdam — and Warner Music Group (WMG) are down 8.0% and 7.1%, respectively. Reservoir Media lost 3.0%. K-pop companies — much like South Korean companies in general — have fared well. Since April 1, SM Entertainment has gained 7.9%, YG Entertainment is up 1.1% and JYP Entertainment has gained 0.7%. HYBE fell 3.4%.

UMG and WMG’s post-tariff declines are slightly greater than the drops in the Nasdaq and S&P 500 of 6.7% and 6.2%, respectively. But both UMG and WMG had strong starts to 2025, and their year-to-date losses of 4.5% and 6.1% are far better than the S&P 500’s 10.2% drop and the Nasdaq’s 15.7% year-to-date decline.

Some live music companies’ stocks have been resilient, too. Live Nation shares are down 3.7% since April 1, while German concert promoter CTS Eventim is up 3.2%. Sphere Entertainment Co., owner of the Sphere venue in Las Vegas, is an exception. Sphere Entertainment shares have plummeted 23.1% since President Trump’s tariff announcement, a far more significant drop than the stocks of other companies — Caesars Entertainment, Wynn Resorts, MGM Resorts — that rely on consumers’ willingness to part with their money in Las Vegas.

For many U.S. media stocks, the direct impact of tariffs is “relatively muted,” wrote Citi analysts in an April 7 report, as many of the companies rely on discretionary spending, not ad revenue. Apple and other tech companies, for example, got an exemption from the 145% tariffs on Chinese imports but must still pay the blanket 20% tariff. Companies that get much of their revenues from subscriptions — Netflix, Spotify, UMG and WMG — will be less impacted.

Music streaming, most notably subscription services, is considered by equity analysts to be safe from whatever tariff-induced economic chaos awaits the global market. “Digital goods are unaffected by tariffs,” wrote TD Cowen analysts in an April 14 investor report. Subscription services, they argued, provide enough bang for the buck, and customers have such an emotional attachment to music that subscribers are unlikely to leave in “meaningful” numbers if the economy goes south.

Streaming and subscription growth slowed in 2024, but many analysts expect improvements to come from a regular drumbeat of price increases, renewed licensing deals and super-premium tiers. That said, analysts believe that Spotify’s latest licensing deals with UMG and WMG, and upcoming deals with other rights holders, better reward labels and publishers for price increases. As a result, TD Cowen slightly lowered its estimates for Spotify’s revenue, gross profit margin and operating income in 2025. Likewise, in an April 4 note to investors, Guggenheim analysts lowered their estimate for Spotify’s gross margin in the second half of 2025.

Companies reliant on advertising revenue will also take an indirect hit. Citi estimates that $4 trillion of imports could generate $700 billion in tariffs and reduce personal consumer and ad spending by 1.9%. Tariffs have ripple effects, too. Because household net worth and personal spending are highly correlated, says Citi, the recent declines in stock prices could reduce personal and advertising spending by 3.0%.

Consumer spending is at the heart of the concert business, but analysts agree that fans’ affection for their favorite artists protects live music from economic downturns. As a result, Live Nation has “less risk than the average business that depends on discretionary spending,” according to TD Cowen analysts.

Advertising-related businesses aren’t so lucky, though. As tariffs raise prices and household wealth declines, personal spending also declines, and, in turn, brands pull back on their advertising spending. Investors’ expectations for advertising-dependent businesses were apparent before April but have become clearer since President Trump’s April 2 tariff announcement. iHeartMedia, which closed on Thursday (April 17) below $1.00 per share for the first time since June 4, 2024, has dropped 35.3% since April 1 and fallen 50.3% year to date. Cumulus Media has fared even worse, dropping 47.5% since April 1 and 62.7% year to date. Townsquare Media has fallen 12.8% in the tariff era and 23.8% year to date.

J.P. Morgan analysts believe iHeartMedia’s full-year guidance of $770 million is “somewhat optimistic” given economic uncertainties and ongoing pressures in the radio business. It forecasts full-year EBITDA of $725 million — nearly 6% lower than iHeartMedia’s guidance. If things wind up going more the way J.P. Morgan predicts than iHeart, it would be a big blow to the company and an unfortunate bellwether for the already struggling radio business. While other music industry sectors look to ride out the tariffs at least in the shorter term, the economic uncertainty introduced by the Trump administration may only hasten radio’s ongoing decline.

As Billboard has noted numerous times in recent weeks, investors are attracted to music assets because they are counter-cyclical, meaning they don’t follow the typical ups and downs of the economy. Consumers will, by and large, stick with their music subscription services and continue going to concerts. But by introducing the tariffs, the Trump regime exposed one of radio’s greatest weaknesses as a business: a greater exposure, due to its reliance on advertising, to the state of the wider economy.

Billboard

Led by Spotify and Live Nation, music stocks surged on Wednesday (April 9) after the U.S. Treasury placed a 90-day pause on most tariffs and recaptured some of the losses from the chaotic previous week.

A week after losing $12 billion in market value, Spotify was one of the top-performing music stocks of the week, gaining 8.0% and offsetting most of the previous week’s 10.3% decline. A 9.8% gain on Wednesday helped improve the streaming company’s two-week loss to 3.1%.

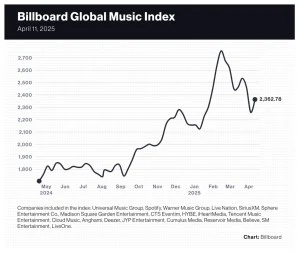

The 20-company Billboard Global Music Index (BGMI) gained 4.6% to 2,362.78 on Wednesday’s 90-day tariff pause. That welcome news recaptured only a fraction of the previous week’s losses, however, and music stocks were hurt by a weakened U.S. dollar and growing fears the U.S. could slip into a recession. After losing 8.2% in the previous week, the index’s two-week loss stands at 4.0%.

Trending on Billboard

U.S. markets rebounded after a miserable week. The Nasdaq rose 7.3% to 16,724.46, bringing its two-week loss to 3.5%. The S&P 500 rose 5.7% to 5,363.36, giving it a two-week decline of 3.9%.

Many markets outside of the U.S. were down, however. In the U.K., the FTSE 100 dropped 1.1%, giving it a two-week loss of 8.0%. South Korea’s KOSPI composite index was down 1.3%, adding to the previous week’s 3.6% decline. China’s SSE Composite Index dipped 3.1% a week after falling 0.3%.

Music streamer LiveOne was the week’s biggest gainer after jumping 18.0% to $0.72. The company’s preliminary results for fiscal 2025 released on Monday (April 7) showed the music streaming company had revenue of more than $112 million, while subscribers and ad-supported listeners surpassed 1.45 million. Even after the large increase, LiveOne shares have fallen 47.4% year to date.

Live Nation, which jumped 7.2% to $129.52 this week, is the only music company to post a gain over the past two weeks. The concert promoter’s share price dropped 3.4% the previous week but, with the help of a 10.9% jump on Wednesday, recovered well enough for a two-week gain of 3.6%.

Record labels and publishers finished the week in the middle of the pack. Warner Music Group fell 1.5% to $29.03, bringing its two-week decline to 8.0%. Universal Music Group was down 1.6%, giving it a two-week decline of 10.7%. Reservoir Media rose 0.7% to $7.10, giving it a two-week deficit of just 2.1%.

Sphere Entertainment Co. is one of the worst-performing music stocks over the past two weeks with an 18.5% decline. The company’s shares finished the week up 1.3%, barely offsetting the previous week’s 19.5% decline. A spike on Wednesday was partially offset by declines of 4.3% and 7.7% on Tuesday (April 8) and Thursday (April 10), respectively.

Most radio companies, which are heavily exposed to slowed advertising spending during recessions, had another down week. Cumulus Media dropped 22.5% to $0.31, bringing its two-week loss to 34.0%. iHeartMedia fell 4.2%, which took its two-week decline to 29.9%. Townsquare Media was down 4.9% this week and 13.6% over the past two weeks. Satellite broadcaster SiriusXM, which was upgraded by Seaport to buy from neutral, gained 2.6% this week, narrowing its two-week loss to 12.0%.

The two Chinese music streaming companies on the BGMI fared poorly despite the recoveries by Spotify, LiveOne and Deezer, which gained 2.3%. Tencent Music Entertainment fell 5.5% to $12.24 but was likely helped by Nomura initiating coverage this week with a buy rating and a $17.20 price target. Cloud Music shares dropped 5.7% to 141.50 HKD ($18.24).

K-pop companies, which bucked the downward trend the previous week, posted declines as well. SM Entertainment fell 8.2%, HYBE dropped 8.1%, JYP Entertainment sank 5.8% and YG Entertainment dipped 4.1%.

Billboard

Billboard

Billboard

HYBE Interactive Media (HYBE IM) secured an additional KRW 30 billion ($21 million) investment, with existing investor IMM Investment contributing another KRW 15 billion ($10 million) in follow-on funding. Shinhan Venture Investment and Daesung Private Equity joined as new investors in the company, which plans to expand its game business using HYBE’s K-pop artist IPs. To date, HYBE IM has raised a total of KRW 137.5 billion ($100 million). With the new money, the company plans to enhance its publishing capabilities and execute its long-term growth strategy by allocating it to marketing, operations and localization strategies to support the launch of its gaming titles.

Live Nation acquired a stake in 356 Entertainment Group, a leading promoter in Malta’s festival and outdoor concert scene that operates the country’s largest club, Uno, which hosts more than 100 events a year. The two companies have a longstanding partnership that has resulted in events including Take That’s The Greatest Weekend Malta and Liam Gallagher and Friends Malta Weekender being held in the island country. According to a press release, 356’s festival season brought 56,000 visitors to the island, generating an economic impact of 51.8 million euros ($56.1 million). Live Nation is looking to build on that success by bringing more diverse international acts to the market.

Trending on Billboard

ATC Group acquired a majority stake in indie management company, record label and PR firm Easy Life Entertainment. The company’s management roster includes Bury Tomorrow, SOTA, Bears in Trees, Lexie Carroll, Mouth Culture and Anaïs; while its label roster boasts Lower Than Atlantis, Tonight Alive, Softcult, Normandie, Amber Run, Bryde and Lonely The Brave. Its PR arm has worked on campaigns for All Time Low, 41, Deaf Havana, Neck Deep, Simple Plan, Travie McCoy and Tool.

Triple 8 Management partnered with Sureel, which provides AI attribution, detection, protection and monetization for artists. Through the deal, Triple 8 artists including Drew Holcomb & the Neighbors, Local Natives, JOHNNYSWIM, Mat Kearney and Charlotte Sands will have access to tools that allow them to opt-in or opt-out of AI training with custom thresholds; protect their artist styles from being used in AI training without consent by setting time-and-date stamp behind ownership; monetize themselves in the AI ecosystem through ethical licensing that can generate revenue for them; and access real-time reporting through Sureel’s AI dashboard. Sureel makes this possible by providing AI companies “with easy-to-integrate tools to ensure responsible AI that fully respects artist preferences,” according to a press release.

Merlin signed a licensing deal with Coda Music, a new social/streaming platform that “is reimagining streaming as an interactive, artist-led experience, where fans discover music through community-driven recommendations, discussions, and exclusive content” while allowing artists “to cultivate more meaningful relationships with their audiences,” according to a press release. Through the deal, Merlin’s global membership will have access to Coda Music’s suite of social and discovery-driven features, allowing artists to engage with fan communities by sharing exclusive content and more. Users can also follow artists and fellow fans on the platform and exchange music recommendations with them.

AEG Presents struck a partnership with The Boston Beer Company that will bring the beverage maker’s portfolio of brands — including Sun Cruiser Iced Tea & Vodka, Truly Hard Seltzer, Twisted Tea Hard Iced Tea and Angry Orchard Hard Cider — to nearly 30 AEG Presents venues nationwide including Brooklyn Steel in New York, Resorts World Theatre in Las Vegas and Roadrunner in Boston, as well as festivals including Electric Forest in Rothbury, Mich., and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival.

Armada Music struck a deal with Peloton to bring an exclusive lineup of six live DJ-led classes featuring Armada artists to Peloton studios in both New York and London this year. Artists taking part include ARTY and Armin van Buuren.

Venu Holding Corporation acquired the Celebrity Lanes bowling alley in the Denver suburb of Centennial, Colo., for an undisclosed amount. It will transform the business into an indoor music hall, private rental space and restaurant.

Secretly Distribution renewed its partnership with Sufjan Stevens‘ Asthmatic Kitty Records, which has released works by Angelo De Augustine, My Brightest Diamond, Helado Negro, Linda Perhacs, Lily & Madeleine, Denison Witmer and others. Secretly will continue handling physical and digital music distribution, digital and retail marketing, and technological support for all Asthmatic Kitty releases.

Symphonic Distribution partnered with digital marketing platform SymphonyOS in a deal that will give Symphonic users discounted access to SymphonyOS via Symphonic’s client offerings page. Through SymphonyOS, artists can launch and manage targeted ad campaigns on Meta, TikTok and Google; access personalized analytics for a full view of fan interactions across platforms; build tailored pre-save links, link-in-bio pages and tour info pages; and get AI-powered real time recommendations to improve marketing campaigns.

Bootleg.live, a platform that turns high-quality concert audio into merch, partnered with Evan Honer and Judah & the Lion to offer fans unique audio collectibles on tour. Both acts are on tour this fall. The collectibles, called “bootlegs,” are concert recordings taken directly from the board, enhanced using Bootleg’s proprietary process, and combined with photos and short videos.

The music business has earned a reputation for being recession-proof. In bad economic times, people still pay for their music subscription services and want to go to concerts. Some synch opportunities may dry up as advertisers make cutbacks, but overall, the music is a hearty business that doesn’t follow typical economic cycles.

Music business stocks, however, aren’t immune to fluctuations in the market and investors’ worries about the increasingly fragile state of the economy. This week, just three of the 20 companies on the Billboard Global Music Index (BGMI) finished with gains, and five stocks had losses in excess of 10%. Despite a host of strong quarterly earnings results in recent weeks, President Donald Trump’s tariffs on goods from Canada, Mexico, China and Europe have caused markets to panic, taking down music stocks along with the industrial and agricultural companies most likely to be affected.

The S&P 500 entered correction territory on Thursday (March 13) when it closed down 10% from the all-time high. The Russell 2000, an index of small companies, was down 18.4% from its peak. Most stocks improved on Friday (March 14) as markets rallied — despite a decline in the University of Michigan’s consumer confidence index — but the first four days of the week were too much to overcome. The S&P 500 finished the week down 2.3% and the Nasdaq composite closed down 2.4%.

Trending on Billboard

Markets outside of the U.S. fared better than U.S. markets. The U.K.’s FTSE 100 dropped just 0.5%. South Korea’s KOSPI composite index rose 0.1% and China’s SSE Composite Index improved 1.4%.

Even though 17 of the 20 companies on the BGMI posted losses this week, the index rose 0.5% to 2,460.71 because of Spotify’s 8.1% gain, and the dollar’s nearly 1% increase against the euro offset the weekly declines of 17 other stocks. Spotify is the BGMI’s largest component with a market capitalization of approximately $117 billion — more than twice that of Universal Music Group’s (UMG’s) $50.2 billion. The stock also received rare good news this week as Redburn Atlantic initiated coverage of Spotify with a $545 price target (which implies 5.5% upside from Friday’s closing price) and a neutral rating.

UMG shares fell 8.8% on Friday, a reaction to Pershing Square’s announcement on Thursday that it will sell 50 million shares worth approximately $1.5 billion. Pershing Square CEO Bill Ackman called UMG “one of the best businesses we have ever owned.” JP Morgan analyst Daniel Kerven admitted the news was “a near-term negative for confidence” in UMG but saw Pershing Square’s decision to sell shares as a move to take profits and re-weigh its portfolio (UMG was 27% of Pershing Square’s holdings) rather than a commentary about UMG’s long-term potential or recent operating performance. UMG shares ended the week down 8.2% to 25.46 euros ($27.78) but remained up 6.5% year to date.

Live Nation shares dropped 6.5% to $119.22, marking the stock’s fourth consecutive weekly decline. During the week, Deutsche Bank increased its Live Nation price target to $170 from $150 and maintained its “buy” rating. On Friday, a judge denied Live Nation’s request to dismiss an accusation that the promoter illegally forced artists to use its promotion business if they wanted to perform in its amphitheaters.

Other U.S.-based live entertainment companies also fell sharply. Sphere Entertainment Co. fell 10.1% to $31.55. MSG Entertainment dropped 1.3% to $31.46 despite Wolfe Research upgrading the stock to “outperform” from “peer perform” with a $46 price target. Vivid Seats, a secondary ticketing platform, fell 28.1% to $2.86 after the company announced fourth-quarter earnings.

Radio companies, which tend to suffer when economic uncertainty causes advertisers to pull back spending, had yet another down week. iHeartMedia fell 12.0% to $1.61. Cumulus Media dropped 11.5% to $0.46. And SiriusXM, which announced layoffs this week, fell 10.1% to $22.67. Year to date, iHeartMedia is down 24.4% and Cumulus Media is down 40.3%. SiriusXM, on the other hand, has gained 1.4% in 2025.

K-pop stocks also fell sharply despite South Korea’s market finishing the week with a small gain. HYBE, SM Entertainment, JYP Entertainment and YG Entertainment had an average decline of 7.4% for the week. Collectively, however, the four South Korean companies have had a strong start to 2025 and, after this week, had an average year-to-date gain of 19.3%.

A federal judge says the Justice Department can move ahead with a key allegation in its antitrust case against Live Nation: That the company illegally forces artists to use its promotion services if they want to perform in its massive network of amphitheaters.

In a written ruling issued Friday (March 14), Judge Arun Subramanian denied Live Nation’s request to dismiss an accusation that the concert giant illegally required artists to buy one service if they wanted to purchase another one — known in antitrust parlance as “tying.”

Ahead of the ruling, attorneys for Live Nation had argued that it was merely refusing to let rival concert promoters rent its venues, something that’s fair game under longstanding legal precedents. But the judge wrote in his ruling that the DOJ’s accusations were clearly focused on artists, not competing firms.

Trending on Billboard

“The complaint explains that due to Live Nation’s monopoly power in the large-amphitheater market, artists are effectively locked into using Live Nation as the promoter for a tour that stops at large amphitheaters,” the judge wrote, before adding later: “These allegations aren’t just about a refusal to deal with rival promoters. They are about the coercion of artists.”

The decision was not on the final merits of the DOJ’s case; the feds must still provide factual evidence to prove that Live Nation actually coerced artists. But at the earliest stage of the case, when courts must assume allegations are true, Judge Subramanian ruled that the DOJ had done enough to move ahead.

The DOJ and dozens of states filed the sweeping antitrust lawsuit in May, aimed at breaking up Live Nation and Ticketmaster over accusations that they form an illegal monopoly over the live music industry. The feds alleged Live Nation runs an illegal “flywheel” — reaping revenue from ticket buyers, using that money to sign artists, then leveraging that repertoire to lock venues into exclusive ticketing contracts that yield ever more revenue.

Among other accusations, the government argued that Live Nation was exploiting its massive market share in amphitheaters — allegedly 40 of the top 50 such venues in the country – to force artists to use its concert promotion services.

“Live Nation has a longstanding policy going back more than a decade of preventing artists who prefer and choose third-party promoters from using its venues,” the DOJ wrote in its complaint. “In other words, if an artist wants to use a Live Nation venue as part of a tour, he or she almost always must contract with Live Nation as the tour’s concert promoter.”

Not so, argued attorneys for Live Nation. In its own court filings, the company said that it merely refuses to rent out its portfolio of amphitheaters to the competing concert promotion companies that artists have hired — and that it is “settled law” under federal antitrust statutes that a company has “no duty to aid its competitors.”

In Friday’s decision, Judge Subramanian said that argument could succeed at trial, but that the DOJ’s basic legal theory was sound enough to survive for now: “The facts may ultimately show that the tying claim here is nothing more than a refusal-to-deal claim,” the judge wrote. “But at this stage, the court’s role is to determine whether the complaint states a plausible tying claim, and it does.”

Live Nation did not immediately return a request for comment. A trial is tentatively scheduled for March 2026.

Live Nation, Sphere Entertainment Co. and MSG Entertainment stocks fell this week as markets were hurt by fears about the impacts of U.S. tariffs, ongoing inflation and government layoffs.

Live Nation, which reported record full-year results on Feb. 20, dropped 11.0% to $127.51, erasing the stock’s entire year-to-date gain. Sphere Entertainment Co. dropped 18.8% to $35.45 following the company’s quarterly earnings on Monday (March 3). MSG Entertainment slipped 7.7% to $31.86.

U.S. stocks had their worst week in months. The Dow slipped 2.1%, the S&P 500 dropped 3.1% and the Nasdaq Composite fell 3.5%. In the U.K., the FTSE 100 dipped 1.5%.

Trending on Billboard

On Friday, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent told CNBC that the U.S. economy would go through an adjustment period with less government spending. “The market and the economy have just become hooked,” he said. “We’ve become addicted to this government spending, and there’s going to be a detox period.”

Doubts about live music’s ability to sustain growth in the current economic climate were captured in a CFRA analyst’s note. “Live entertainment and exorbitant ticket prices have raised investor concerns whether record demand will recede with a rising household cost of living and lower consumer confidence,” analyst Kenneth Leon wrote in a March 5 note to investors.

Nevertheless, Leon maintained its $135 price target and upgraded Live Nation shares to “hold” from “sell.” The company, he added, “is a market leader in tickets and continues to fund large capital expenditures to expand its own venues.”

Sphere Entertainment Co. shares fell 13.6% on Monday (March 3), the day the company released quarterly earnings, and slipped another 6% through Friday (March 7). Revenue fell 2% to $308.3 million from the prior-year period, although revenue for the Sphere venue was up 1%. At the company’s MSG Networks division, revenue dropped 5% and its $34.2 million operating profit turned into a $35 million operating loss.

Numerous analysts made downward revisions to their Sphere models after the earnings release. Benchmark dropped its price target to $35 from $36. JP Morgan cut its price target to $54 from $57. And Seaport cut its earnings-per-share estimate for the current quarter to -$2.03 from -$1.66.

Other companies in the live entertainment space also declined. MSG Entertainment fell 7.7%, Vivid Seats dropped 3.9%, Eventbrite dipped 2.1% and German concert promoter CTS Eventim lost 0.6%. Many other companies that depend on consumer discretionary spending also fell this week, including Expedia Group (down 6.9%), Hyatt Hotels (down 3.7%) and cruise operator Carnival Corporation (down 13.7%).

The 20-company Billboard Global Music Index (BGMI) dropped for the third consecutive week, falling 6.3% to 2,449.61. Although the index is up 15.3% year to date, it has fallen 11.1% in the last three weeks. Most of the index’s most valuable companies were among the week’s winners. Other than Live Nation, none of the 13 stocks that lost ground are among the index’s most valuable companies — with one major exception.

Spotify, the BGMI’s largest single component, dropped 12.6% to $531.71, putting the stock 18.5% below its all-time high set on Feb. 13. With a market capitalization of roughly $105 billion, Spotify is large enough to influence the fortunes of an index that contains 19 other stocks. Despite having a few off weeks, however, Spotify is the best-performing music stock of the last year and has gained 14.0% year to date.

Universal Music Group (UMG) shares rose 6.8% on Friday following the company’s fourth-quarter earnings release on Thursday (March 6), though itended the week up just 3.3%. Warner Music Group appeared to benefit from investors’ enthusiasm about UMG’s earnings as its shares rose 2.0% to $34.39.

iHeartMedia CEO Bob Pittman caused his company’s stock to spike 23% on Thursday after an SEC filing revealed the executive purchased 200,000 shares. Investors noted the CEO’s optimism in his company’s future, and the stock ended a downward slide to finish the week up 3.4% to $1.83.

The week’s biggest gainer, Chinese music streaming company Tencent Music Entertainment (TME), rose 9.2% to $13.31. TME benefitted from a surge in Chinese stocks as comments made during the country’s parliamentary meetings this week fueled optimism that the government will provide stimulus for Chinese technology companies. The company will release fourth-quarter earnings on March 18.

Cumulus Media was the week’s biggest loser after dropping 27.8% to $0.52. The company revealed on Friday that it received a warning from the Nasdaq stock exchange that it faces a de-listing for failing to meet the minimum shareholders’ equity threshold of $10 million.

In 2000, after Larry Magid sold his Philadelphia promotion company Electric Factory Concerts for an undisclosed sum, the buyer, Robert Sillerman, called at 12:30 a.m. to congratulate him. Then Sillerman said, “Now you congratulate me.”

“OK, congratulations on what?” Magid asked Sillerman, his new boss.

“Well, we merged,” Sillerman said.

Sillerman, then executive chairman of SFX Entertainment, was referring to his company’s $4.4 billion dollar sale to San Antonio, Texas-based broadcast behemoth Clear Channel Communications, which he’d finished at almost exactly the same time he bought Magid’s company. Thus, Magid would become an employee not of SFX, but Clear Channel, for the next five years — a period that was not easy for Magid, who had been Philly’s top independent promoter since roughly 1968, when he opened the Electric Factory club with a Chambers Brothers show. “It just seemed to be a struggle,” he recalls. “There were a lot of meetings, none of which we were used to.”

All this took place 25 years ago this week — Clear Channel’s purchase of SFX was announced Feb. 29, 2000 — and it would change the concert business forever. For decades, the live industry was ruled by unaffiliated local promoters like Magid, who ran their cities like local cartels as rock’n’roll evolved from tiny events to stadium concerts. Sillerman had spent the past three years buying out those local promoters — an acquisition spree that included big names like the late Bill Graham’s company in the Bay Area (for a reported $65 million), Don Law‘s company in Boston ($80 million) and lesser-known indies such as Avalon Attractions in Southern California ($27 million). The result was a consolidated behemoth that guaranteed advance payments of up to millions of dollars for top artists to do national tours, prompting promoters to raise prices for tickets, parking, food and alcohol to pay for their costs — all of which has become standard industry practice for concerts over the ensuing 25 years.

Trending on Billboard

Then Sillerman turned around and sold everything to Clear Channel.

By that point, the concert business no longer operated as a collection of regional fiefdoms — in which Bill Graham Presents and its Bay Area competitors competed for, say, a U2 date — but as a central entity in which SFX booked U2’s entire U.S. tour. In 2000, SFX was to promote 30 tours, from Tina Turner to Britney Spears to Ozzfest, “light years beyond what any other company has ever attempted,” Billboard reported at the time. “It has become nearly impossible for a major act to tour without SFX being involved in some way.”

“What [Sillerman] accomplished revolutionized the business. It was probably the biggest impact in the industry since the Beatles,” recalls Dennis Arfa, longtime agent for Billy Joel and others, who sold his talent agency to SFX and worked there for several years. “Bob took the business from a millionaire’s game to a billionaire’s game. From the street to Wall Street.” (Sillerman died in 2019.)

Sillerman’s sale to Clear Channel offered an even more tantalizing promise for the concert business: linking hundreds of top radio stations with top promoters and venues — “taking advantage of the natural relationship between radio and live music events,” Lowry Mays, Clear Channel’s chairman and CEO, said at the time of the sale.

But the venture ultimately failed. Many of the SFX promoters never felt they fit in at San Antonio-based Clear Channel. “We knew we were dealing with a very conservative family out of Texas — that was people’s main concern,” recalls Pamela Fallon, who’d worked with Boston promoter Don Law when SFX bought his company, then became a Clear Channel senior vp of communications. “We were pretty footloose and fancy-free in the concert business.”

Clear Channel’s meetings-heavy corporate culture reflected Mays, a former Texas petroleum engineer who, by 2000, had expanded the company from a single station in the early 1970s to a media giant with 867 radio stations and 19 TV stations, a robust billboard business and a weekly consumer base of 120 million. Along the way, Mays helped build conservative talk radio, using Clear Channel-owned syndicate Premiere Radio Networks to expand the reach of Rush Limbaugh, Laura Schlessinger and other right-wing hosts.

In 2001, writing in Salon, former Billboard reporter Eric Boehlert, later a progressive media critic, called Clear Channel “radio’s big bully.” In 2003, U.S. Senators questioned Mays about Clear Channel’s business practices during a committee hearing on media consolidation; the Eagles’ Don Henley showed up to accuse Clear Channel of strong-arming artists to work with the company, as opposed to its competitors. John Scher, a New York promoter who did not sell to SFX, Clear Channel or Live Nation, adds today: “The merger with Clear Channel, in some markets, was the death knell to local promoters: Sell to Clear Channel, or not be able to do any significant marketing with their radio stations.”

But the Clear Channel vision of combining radio with concerts had a fundamental flaw: It may have violated antitrust laws, as a rival Denver promoter claimed in a 2001 lawsuit, alleging the company blacked out radio airplay for artists who booked tours with Clear Channel rivals. (The parties settled in 2004.)

Other flaws in the “mega-merger,” as Billboard referred to it in a March 2000 front-page headline, were less public. In every market, according to Angie Diehl, a longtime marketing exec for promoters, who worked for both SFX and Clear Channel at the time, there were multiple competing radio stations that could present a concert. There were also multiple competing rival concert promoters. Clear Channel aimed to lock down all of these entities in one city so the company could control all the marketing, advertising and promotion of, say, U2.

“But there’s only one U2,” Diehl says. “The artist still dictates what they want. If you want U2 to play for you, and U2 says, ‘Well, we want KROQ to present the show,’ that’s who’s going to present the show.” Arfa adds that the combined company “never quite lived up to its synergistic ambitions.”

Perhaps recognizing this reality, Clear Channel spun off its concert division in 2005 — which would come to be known as Live Nation, led by Michael Rapino, a Canadian promoter who’d also sold his company to SFX. At first, despite emerging as the world’s biggest promoter, Live Nation struggled with hundreds of millions of dollars in debt — $367 million from the initial Clear Channel spin-off, growing to $800 million due to venue-maintenance fees over the next few years. But Rapino steered the promoter into a merger with ticket-selling giant Ticketmaster in 2008, providing crucial cashflow for years to come. “Until the Ticketmaster merger, I don’t think it made any money,” Scher says, adding that he used to book 30 to 40 New York arena shows per year, but industry dominance among Live Nation and top rival AEG has forced him to downsize to three or four. “They are formidable adversaries.”

In the long run, Live Nation solved a problem that the short-lived, SFX-infused Clear Channel Communications never quite figured out. (Clear Channel Communications renamed its radio operation iHeartMedia in 2014; Mays died in 2022.) So despite the promise — and the fears — that Clear Channel would take over the concert business and shut out competition, it was actually what came before and after the $4.4 billion acquisition that proved far more significant. Before the acquisition, SFX was the entity that expanded concert promotion from regional to national; after the acquisition, Live Nation made the concert industry more profitable than ever.

The promise of Clear Channel “synergy,” during its concert-industry excursion from 2000 to 2005, never fully paid off. “The idea was they were going to be able to promote all our concerts over their radio stations,” recalls Danny Zelisko, a Phoenix promoter who sold his company, Evening Star Productions, to SFX. “But at Clear Channel, [promoters] were the stepchild in the backseat. We were almost a dirty word. There was never anything about bringing the radio and the concerts together. It just wasn’t meant to be.”

A busy year in high-margin amphitheaters and arenas pushed concert promoter Live Nation to a record $2.15 billion in adjusted operating income (AOI) in 2024, up 14%, on record revenue of $23.16 billion, up 2%.

In the concerts division, full-year revenue rose 2% to $19.02 billion. Despite having 30% fewer stadium shows in 2024, the total number of fans grew to a record 151 million from more than 50,000 Live Nation events. A heavy slate of concerts at arenas and amphitheaters, where Live Nation can offer VIP experiences and capture more revenue from food and beverage sales, helped AOI climb 65% to $529.7 million and AOI margin — AOI as a percentage of revenue — reach a record 2.8%.

Ticketing revenue for the full year increased 1% to $2.99 billion while AOI dropped 1% to $1.12 billion. Ticketmaster had 23 million net new enterprise tickets that were signed in 2024, with two-thirds coming from international markets.

Trending on Billboard

Sponsorships and advertising revenue grew 9% to $1.2 billion and AOI rose 13% to $763.8 million. Led by festivals in Latin America and Europe, international markets were up double digits. The number of new clients increased 20%.

Live Nation is expecting 2025 will top its record-setting 2024. Through mid-February, stadium shows are up 60% from the prior-year period and 65 million tickets have been sold for Live Nation concerts, a double-digit annual increase. Ticketmaster’s transacted ticketing revenue for 2025 shows is up 3% to 106 million tickets, due mainly to an increase in concert demand.

The current year “is shaping up to be even bigger thanks to a deep global concert pipeline, with more stadium shows on the books than ever before,” CEO Michael Rapino said in a statement. Currently, Live Nation’s stadium tours for 2025 include Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter tour, Morgan Wallen’s I’m The Problem Tour, Kendrick Lamar and SZA’s Grand National Tour, and Post Malone and Jelly Roll’s Big Ass Stadium Tour.

Consolidation fourth-quarter revenue dropped 2% to $5.68 billion as concerts revenue dipped 6% to $4.58 billion and ticketing and sponsorships and advertising grew 14% and 10%, respectively. Fourth-quarter AOI fared better, however, rising 35% to $157.3 million despite concerts AOI falling 16%.

Live Nation is ending its “concerts all summer long” program at the company’s amphitheaters and plans to replace the multi-show offering with something different, company officials tell Billboard. On Tuesday (Feb. 18), the Live Nation Lawnie Instagram page announced the end of the six-year-old program, in which music fans paid a flat fee for a […]

HipHopWired Featured Video

Source: NurPhoto / Getty

Live Nation Urban, helmed by its president Shawn Gee, announced on Thursday (Feb. 13) an investment partnership in the Breakr platform, which aids creators in marketing their wares. Breakr, founded by a pair of brothers, aims to empower recording labels, online content creators, and related creatives in their marketing endeavors.

Breakr, founded in 2020 by siblings Anthony and Ameer Brown, frames its company as one that “operates at the intersection of music, creators, and technology, empowering music labels, creative agencies, owned media properties, and brands to discover, select, pay, and contract with independent online content creators for promoting songs, products, and services.”

With the backing of Live Nation Urban, Breakr introduced its BreakrPay™️ system, which puts its focus on making paying creatives a seamless process and cutting down on payment delays. In short, BreakrPay™️ is designed to make sure that content creators and influencers, all of whom truly push brands to the forefront, are paid equitably and on time while doing away with the outdated net 30-90 payout structure.

Breakr has broken deals in the past with Sony Music, Interscope, and BMG among other partners in order to push through innovative musicians in the TikTok and Instagram spheres to break their records and reach larger audiences. Breakr has also worked with brands such as Celsius, Samsung, Billboard, and more.

“The creator economy has changed the way we all connect with audiences, driving innovation and economic activity at an unprecedented scale. Breakr is a tech platform that was a core part of Live Nation Urban’s marketing mix for the better part of a year. After meeting the founders and understanding their vision, it was an easy decision for us to invest in Tony and Ameer and their trail-blazing platform,” said Shawn Gee, Founder and President of Live Nation Urban in a statement. “Our investment reflects our belief in the founders and in the transformative power of creators and the technology that empowers them to thrive.”

Anthony Brown, Co-Founder and Co-CEO of Breakr added in. the statement, “From Breakr’s founding, projects like our #RoadtoRollingLoud competition with Rolling Loud to our extensive work with indie labels as well as the ‘Big 3,’ we’re committed to creating opportunities, discovering talent, and financially empowering creators and change-makers worldwide. Our partnership with Live Nation Urban and Shawn is the exciting beginning of a new chapter where we can expand our vision further than ever before, particularly with brands.”

“Breakr’s proprietary technology is revolutionizing the way brands and agencies connect with creators, offering seamless campaign management, real-time analytics, and instant payments—all within a single ecosystem. Our white-label infrastructure empowers partners to scale their operations effortlessly while maintaining full control over their campaigns and finances. This partnership with Live Nation Urban will allow us to expand our reach and continue developing industry-leading solutions that drive measurable impact in the creator economy,” shared Ameer Brown, Co-Founder and Co-CEO, of Breakr.

The Live Nation Urban investment will be under a new venture fund known as the Black Lily Capital Fund and has involvement from the larger Live Nation outfit. This fund will grant support to Black founders who work within or are connected to the realm of live music with a special dedication given towards newer businesses.

Learn more about Breakr here.

Source: Live Nation Urban / Breakr

—

Photo: Breakr/Live Urban Nation/Getty

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio