Live nation

Trending on Billboard

Olivia Dean spoke, Ticketmaster has taken action.

Last Friday, Nov. 21, the English artist took a moment out of her busy scheduled to lay one on Ticketmaster, Live Nation and AEG Presents for the resale ticket prices to her 2026 North American tour.

Tickets to her The Art of Loving Tour went on sale to the general public that day, and sold out in minutes. Though, with some resale prices climbing into the thousands of dollars, Dean had some harsh words.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

“@Ticketmaster @Livenation @AEGPresents you are providing a disgusting service,” she wrote on Instagram Stories. “The prices at which you’re allowing tickets to be re-sold is vile and completely against our wishes. Live music should be affordable and accessible and we need to find a new way of making that possible. BE BETTER.”

Ticketmaster is trying to “do better,” by capping all future ticket resale prices for the tour on its platform and refunding fans for any markup they already paid to resellers on Ticketmaster.

According to a statement from Ticketmaster, which merged with Live Nation in 2010, Ticketmaster has activated its Face Value Exchange for the tour, with immediately effect, and without transfer restrictions. That move should ensure that any future ticket sales on its site are capped at the original price paid — with no added fees, the message continues.

Refunds will be processed by Dec. 10, the company insists, though may take additional days to post, depending on individual banks.

“We share Olivia’s desire to keep live music accessible and ensure fans have the best access to affordable tickets,” comments Michael Rapino, CEO, Live Nation Entertainment. “While we can’t require other marketplaces to honor artists’ resale preferences,” Rapino adds, “we echo Olivia’s call to ‘Do Better’ and have taken steps to lead by example. We hope efforts like this help fans afford another show they’ve been considering—or discover someone new.”

The ticketing giant shared some insights into sales for the tour, for which demand was so “high,” the artist added three additional nights at the Madison Square Garden.

After reviewing all sales, reads Ticketmaster’s message, less than 20% of primary tickets were listed for resale –“showing that Olivia’s demand was driven by genuine fans who intend to go to the show rather than resellers out for profit.”

Dean had been opening for Sabrina Carpenter on the final leg of the U.S. singer’s Short n’ Sweet Tour, and announced her own North American headlining trek earlier in November.

A London native, Dean’s star has been on the rise of late, thanks in part to her Saturday Night Live debut Nov. 15, and her subsequent trip to Australia, where she performed an exclusive open-air show in Sydney and at the 2025 ARIA Awards.

That whistlestop trip down under translated immediately into a No. 1 on the ARIA Chart, as “Man I Need,” lifted 2-1 for the very first time. Dean currently has four tracks on the Billboard Hot 100, including “Man I Need” at No. 5. The 26-year-old’s The Art of Loving album is also slotted at No. 5 on the Billboard 200 dated Nov. 22.

Dean’s 2026 tour kicks off in the U.K. and Europe, beginning with Glasgow, Scotland, in April, and wraps June 20 in Dublin. Her U.S. summer trek is slated to kick off in San Francisco on July 10, and she’ll be making stops in Los Angeles, New York City, Atlanta, Toronto, Las Vegas, Boston, Houston and finish up in Austin on Aug. 28.

Trending on Billboard

Ball Park Music are getting another boost from their career-defining support slot on Oasis’ blockbuster Australian reunion tour, with the Brisbane five-piece featured in the latest instalment of Live Nation’s Soundcheck series.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

The behind-the-scenes episode documents the band stepping onto the biggest stages of their career, performing to arena-sized crowds across the country as Oasis returned to Australian venues for the first time in more than a decade.

The new video follows Ball Park Music from soundcheck through to showtime, capturing the emotional and technical build-up before the house lights drop. The band — who have long cited Oasis as formative influences — are shown tuning up backstage, taking in the scale of the arena, and reflecting on the surreal nature of opening for one of the most culturally dominant bands of the ’90s and 2000s.

“It’s hard to even describe what it feels like to open for Oasis,” the band say in the episode. “We’ve all grown up with their music and to suddenly be standing there, playing before them, it’s surreal. You can feel the crowd buzzing from the moment you walk out. It’s a mix of nerves and pure joy. Nights like that remind you why you started playing music in the first place.”

The Oasis tour itself has been one of the major Australian live music stories of 2025, prompting rapid sellouts across multiple cities and adding extra dates to meet demand. For Ball Park Music, the run marks a significant step up following a strong year that already included major touring and chart success.

Earlier in 2025, the group scored their first ARIA No. 1 album with Weirder & Weirder, extending their streak of consecutive top-10 entries on the ARIA Albums Chart. Until then, three of the band’s releases had stalled at No. 2: Puddinghead (2014), Ball Park Music (2020), and Weirder & Weirder (2022).

The Soundcheck episode portrays this shift in real time. Cameras capture the band navigating the fast pace of arena production, walking onstage to tens of thousands of fans, and later watching Oasis’ performance from the side of the stage. There are quieter moments too: the group describing their pre-show nerves, laughing about technical mishaps, and taking in the “full-circle” nature of the moment.

Live Nation’s Soundcheck series has previously highlighted artists across the Australian touring landscape, including Anna Lunoe, Teen Jesus and the Jean Teasers, Coterie and Dallas Frasca. The Ball Park Music instalment continues the focus on documenting live performance culture from the inside — showing the realities and emotions artists experience at key turning points in their touring career.

Watch the extended episode of Live Nation’s Soundcheck with Ball Park Music and Daphne Berry here.

Trending on Billboard

Attorneys for Live Nation and Ticketmaster are hoping to end the Department of Justice’s sweeping antitrust case before it goes to trial, filing a 51-page summary-judgment motion that argues the claims of the DOJ and the 41 state AGs who joined the suit have failed to prove that the concert giant operates like a monopoly.

The filing, submitted to Federal Judge Arun Subramanian in the Southern District of New York, casts the government’s lawsuit as an overreach that collapses due to a lack of evidence.

Related

Live Nation’s attorneys at Latham Watkins and Cravath, Swaine & Moore allege that the DOJ began the litigation with harsh accusations against Live Nation, saying the DOJ accused the global promoter of operating “multiple, self-reinforcing monopolies” replete with “‘systematic’ and ‘intentional’ corruption of competition across ‘virtually every aspect of the live music ecosystem.’”

“Strong words,” Live Nation lawyers write. “If there was a lick of truth to them, one would expect Plaintiffs to now have mountains of evidence… And yet… Plaintiffs have barely a molehill.”

Live Nation’s attorneys go on to argue that the government has not proven the most fundamental element of a monopolization claim: monopoly power. Citing long-standing Supreme Court precedent, the company notes that “monopoly power is the foundational element of every monopoly maintenance case,” and insists the DOJ has failed to meet that threshold.

Instead of using traditional evidence of monopoly power to make its case – like high prices or significant barriers to entry — Live Nation says the DOJ case is built on inferences and derivative legal arguments, relying on “gerrymandered” market definitions to make its case. According to the motion, the government relies on a convoluted formula to define a “major concert venue,” singling out venues with capacities above 8,000 that host 10 or more concerts during at least one year in the 2017–2024 period. Stadiums, large theaters, smaller amphitheaters and many other common concert venues are excluded.

Related

Live Nation argues this structure ignores how competition in the concert business actually works, noting that “made-for-litigation markets plainly do not encompass ‘the area of effective competition’ that the law requires,” pointing out that rival ticketing companies such as SeatGeek, AXS, Eventim and Paciolan compete broadly and do not restrict their efforts to the DOJ’s handpicked venues.

Company attorneys argue that the DOJ’s narrowed market definition is the only way the government can claim Ticketmaster has a monopoly. According to Live Nation, the DOJ’s own expert calculated that Ticketmaster’s market share would fall from 86% to 49% if stadiums — venues the DOJ included when it challenged the Live Nation–Ticketmaster merger in 2010 — were defined as “major concert venues.”

“Far from having the ‘power to exclude competition,’ Ticketmaster has lost over 30 points of market share since the merger,” in 2011 between Live Nation and Ticketmaster, the company’s attorneys claim.

Beyond market definition, the company spends considerable space pushing back on one of the DOJ’s central theories: that Ticketmaster’s long-term exclusive ticketing contracts with venues hamper competition. Live Nation argues that exclusivity has been the industry standard in North America for decades and remains preferred by venues because it leads to higher up-front payments, smoother operations, integrated technology, and reduced consumer confusion about where to buy tickets.

“Every venue witness has testified that they seek and prefer exclusive ticketing contracts,” the memo reads, arguing that no venue manager interviewed in the lawsuit claimed to be coerced into an exclusive contract or pushed for a multi-ticketer system and was prevented from pursuing one.

Related

The DOJ has also accused Live Nation of tying concert promotion to its Ticketmaster’s offering, alleging that the company threatens or retaliates against venues by steering Live Nation-promoted tours away from buildings that choose rival ticketing services. Live Nation’s lawyers said evidence behind these allegations was paper thin, writing, “At most three venue witnesses support this claim—one in the last five years. … Three out of thousands could not possibly prove the market-wide anticompetitive effects required for a monopolization claim.”

According to the filing, the rest of the government’s evidence comes from rival ticketing companies — statements Live Nation calls inadmissible hearsay that cannot survive summary judgment. The company further notes that similar allegations were investigated by the DOJ in 2019, leading to a modification of the consent decree but not a finding of systemic misconduct. Since then, Live Nation says, “the outside antitrust monitor… has not reported a single violation.”

The company also disputes the government’s claims tied to Live Nation’s amphitheaters. Prosecutors allege that Live Nation illegally ties access to amphitheaters to its own promotion services, discouraging artists from working with independent promoters. Live Nation responds that this theory is contradicted by how touring actually works: artists, it says, control routing decisions, approve venues, set ticket prices, and choose their promoters based on guarantees and deal terms. The filing points out that the DOJ deposed only one artist throughout the entire case and that his testimony did not support the government’s claim. According to the motion, the artist “answered, without ambiguity or qualification,” that he had not been coerced to hire Live Nation as a condition of playing an amphitheater. “That is no basis for a trial,” the filing states.

Live Nation insists its amphitheaters are a competitive asset and not a leverage point to suppress competition. The company analogizes amphitheaters to tools of the trade: promoters, not artists, rent the venues, and the ability to offer those venues is part of how promoters compete for tours. The motion argues that amphitheaters typically are not rented to competing promoters for structural business reasons, not because of an anticompetitive scheme.

Related

Throughout the filing, Live Nation repeatedly invokes the DOJ’s own prior statements from 2010 in which the agency acknowledged the benefits of the company’s vertical integration with Ticketmaster. In approving the Live Nation–Ticketmaster merger, the DOJ wrote that “vertical integration can produce procompetitive benefits” and that “most instances of vertical integration… are economically beneficial.”

Live Nation attorneys also argue regularly in their memo that the DOJ cannot show harm to consumers—not through higher prices, a drop in shows or a decline in concert quality. Citing Microsoft and other precedent, Live Nation argues that such evidence is indispensable in a monopolization case. The filing states, “There must be evidence of actual harm to consumers; ‘harm to one or more competitors will not suffice.’ Plaintiffs never show that anything Defendants have done harmed artists or venues.”

The motion concludes by arguing that after extensive discovery, there are no triable issues remaining to be adjudicated. “The faithful application of law to the evidence adduced should yield summary judgment for Live Nation and Ticketmaster,” the filing states.

Attorneys for the government will have their chance to file a response in the coming weeks before Judge Subramanian determines whether the case proceeds to trial. If the summary-judgment motion is granted, much or all of the government’s case could be dismissed outright or the government could be forced to refile parts of its lawsuit.

Live Nation is also facing a lawsuit by the Federal Trade Commission over how the company operates its secondary ticket business.

Trending on Billboard Live Nation Australia and the Australian Open are expanding the Grand Slam’s entertainment footprint with AO Live Opening Week, a new four-night concert series launching Jan. 13–16, 2026. Explore See latest videos, charts and news The announcement arrives under a growing trend of major sporting events integrating large-scale live music programming, aligning […]

Trending on Billboard

Music fans would choose a concert over having sex if it meant seeing their favorite artists perform, according to a recent survey from concert promoter giant Live Nation.

Titled “Living for Live,” the global report includes insights from more than 42,000 fans (defined as anyone who attended a concert in the last year) aged 18 to 54 across 15 different countries, including all of North America, most of Western Europe, Australia, Japan, Thailand and Brazil.

Related

According to the survey, fans have named concerts as the world’s top form of entertainment, outranking attending movies, sporting events and even having sex, with 70% of respondents saying they would choose a concert by their favorite artist over lovemaking.

“This report confirms what we’re seeing on the ground everywhere,” said Russell Wallach, Live Nation’s global president of media and sponsorship, in a statement. “Live music isn’t just growing, it’s shaping economies, influencing brands, and defining culture in real time. Fans have made live the heartbeat of global entertainment, and it’s now one of the most powerful forces driving connection and growth worldwide.”

The study is meant, in part, to drive new insights about the millions of fans who attend concerts every year on behalf of the 1,500 major brands and sponsors that spent $1.2 billion with the company in 2024, according to Live Nation’s year-end financials.

Related

The study found that 35% of fans plan to attend at least four concerts per year, while 29% of festivalgoers plan to attend at least four festivals per year. The report also found that 85% of fans said music was a core part of their identity, that 77% felt part of something bigger at shows, and that, among parents, the number one passion many hoped to pass on to their children was a love for live music.

The report also found that demand for female artists was continuing to grow, with 76% of responding fans reporting that they wanted more female-led lineups and 60% reporting a desire to see more festivals spotlight female talent.

The report covers a broad range of how fans view the importance of live music in their lives, the global nature of touring and the economic impact touring can have on local markets. A complete summary of the report can be found at livingforlive.livenationforbrands.com.

Trending on Billboard

There were flames, fireworks, and an unexpected blast of “Smoko,” as Metallica’s M72 tour stopped by Brisbane’s Suncorp Stadium on Wednesday night, Nov. 12.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

The Rock Hall-inducted metal giants have been extra sweet to audiences on this trek, their first down under since 2013, by playing a homegrown classic on each tour date.

For their tour opener Nov. 1 at Perth’s Optus Stadium, the Bay Area legends carved out a rendition of John Butler’s “Zebra,” which the Western Australian native responded to with his own cover of Metallica’s “Enter Sandman.”

Then, at Adelaide Oval on Nov. 5, the rockers covered INXS’ Billboard Hot 100 leader “Need You Tonight,” and segued into the Angels’ classic from 1976, “Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again,” led by bass player Robert Trujillo at the mic. For their Melbourne show, at Marvel Stadium, Metallica covered “Prisoner of Society” the alternative rock trio the Living End.

The rumor mill was grinding away ahead of Metallica’s lone show in the Sunshine State. Would they cover a Powderfinger song, or the Go-Betweens? Perhaps the Saints? Or maybe a leftfield choice by performing the Bee Gees, the Veronicas or even Keith Urban.

As it turned out, Metallica hit the right note with a cover of the Chats’ “Smoko,” originally released on the Sunshine Coast punk rock act’s 2017 EP, Get This in Ya!!. Trujillo once again took vocal duties, accompanied by lead guitarist Kirk Hammett. “We like to celebrate music from your hood,” Trujillo remarked.

A “smoko” is, for those uninitiated, an Australian expression for a break from work, or more specifically, a pause to smoke.

Eamon Sandwith and Co. were thrilled with the nod. “Stoked to make it to the ‘doodle’ section of the set, thanks Metallica,” reads a social post from the ARIA Award-winning band.

Metallica opened the show with a mainscreen montage of the fan photos, set to “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ’n’ Roll)” by AC/DC, whose own tour of Australia kicked off at the same time, 1,000 miles south of Brisbane, at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. AC/DC will visit Brisbane’s Suncorp Stadium, twice, in December.

“Thank you, we missed you a lot,” frontman James Hetfield told the audience, gathered on an unusually cool November night. “We’re very grateful to be here. This is love.”

Hetfield also insisted that he had “the best job in the world,” which he well could, before Metallica launched into “Sad But True,” an anvil of a song.

Metallica may have mellowed through the years, but they’re still hard as hammers, which they proved with a set that flew high and never came down. The encore, of “Master Of Puppets,” “One,” and “Enter Sandman” could’ve woken the dead. Maybe the fourpiece was tipped off that the venue was once Paddington Cemetery, a burial ground.

Late in the set, Hetfield welcomed the capacity house as members of the “Metallica family,” some as veterans, others newcomers. “That’s why we’re here. To forget all the bull**** in life.” As good parents, Hetfield, Hammett, Trujillo and drummer Lars Ulrich stayed on stage well after the last chord rung out, to share gifts of drumsticks, guitar picks and take turns in thanking the fans.

Produced by Live Nation Australia, the tour continues at Sydney’s Accor Stadium (Nov. 15) and wraps up Nov. 19 at Auckland’s Eden Park. Evanescence and Suicidal Tendencies are the support on this leg of the M72 World Tour.

Trending on Billboard

Music stocks had their worst week in three months, as most companies that reported earnings this week were penalized for not offering more to investors. Spotify, Live Nation, SM Entertainment and Reservoir Media all finished the week ended Nov. 7 in the red — though live entertainment companies Sphere Entertainment and MSG Entertainment bucked the trend by posting sizable gains after putting out their quarterly earnings reports.

The 19-company Billboard Global Music Index (BGMI) fell 5.0% to 2,703.11 as losers outnumbered winners 15 to 4. After soaring earlier in the year, the BGMI is now 13.3% below its all-time high of 3,117.20 (in the week ended June 30) and is now equal to its value in early May.

Related

iHeartMedia was a notable exception to the carnage. The radio company’s shares jumped 55.9% to $4.63 after a report at Bloomberg said the company is in talks to license its podcasts to Netflix. Netflix is known to be seeking video podcast content and has also reportedly approached SiriusXM about distributing its podcasts. The week’s high mark of $4.77, reached on Thursday (Nov. 6), was iHeartMedia’s highest mark since March 17, 2023.

Sphere Entertainment Co. rose 12.6% to $77.08 after the company’s earnings report on Tuesday (Nov. 4) showed an improvement in the Sphere segment’s operating loss. Led by the popularity of The Wizard of Oz, the number of film viewings, called The Sphere Experience, rose to 220 from 207 in the prior-year period. Sphere’s shares are now up 81.5% year to date.

MSG Entertainment (MSGE) shares gained 5.3% to $46.51 following the company’s earnings report on Thursday. MSGE’s revenue jumped 14% to $158.3 million while its operating loss deepened to $29.7 million from $18.5 million a year earlier. J.P. Morgan raised its price target to $47 from $41, citing management’s comments on pricing and higher expectations for the Christmas Spectacular at Radio City Music Hall.

Related

Companies such as Live Nation and Spotify reported solid results but suffered a large share price decline — part of a trend that extends well beyond music companies, Bernstein analysts wrote in an investor note on Thursday: “We’ve seen a brutal theme emerge across the consumer [technology, media and telecommunications] sector: stocks that deliver perfectly in-line or modestly better than expected results are still getting sold.” Growth is not good enough, they explained, and investors are “shooting first and asking questions later” when a company doesn’t have a “bulletproof guide” for the next year or two.

Live Nation shares ended the week down 6.0% to $140.51 after the company reported third-quarter earnings on Tuesday (Nov. 4). Despite showing continued revenue and adjusted operating income growth, Live Nation’s share price fell 10% the following day, though the price recovered some losses in each of the next two trading days. Bernstein maintained its $185 price target and called the sell-off a buying opportunity, but numerous other analysts lowered their Live Nation price targets, including Oppenheimer (from $180 to $175), Evercore (from $180 to $168), Morgan Stanley (from $180 to $170), J.P. Morgan (from $180 to $172) and Roth Capital (from $180 to $176).

Also releasing third-quarter earnings on Tuesday was Spotify, whose stock fell 5.9% to $616.91 in the aftermath. The company reported 12% revenue growth, but the title of Bernstein’s investor note on Tuesday perfectly captured Spotify’s need to constantly impress investors: “When you trade at 50x EPS, you’d better make sure everybody’s happy.” Meanwhile, J.P. Morgan called the company’s fourth-quarter outlook “slightly mixed”: The company’s guidance on monthly average users and gross margin were “above expectations,” it said, but guidance on subscribers, revenue and operating income were lighter than expected. Guggenheim lowered its price target to $800 from $850, noting that results met expectations but that “questions remain” on Spotify’s ability to improve margins through price increases.

Related

Elsewhere, Reservoir Media fell 3.0% to $7.37 following the release of its quarterly earnings on Tuesday, while Warner Music Group, which reports earnings on Nov. 20, fell 5.4% to $30.23. Universal Music Group, which reported earnings on Oct. 30, dropped 3.4% to 22.48 euros ($26.01).

K-pop company SM Entertainment fell 14.1% to 102,600 KRW ($70.47), having dropped 9.6% in the two days following the release of third-quarter results on Thursday. Other K-pop companies also experienced large declines as HYBE dropped 10.4%, JYP Entertainment dipped 11.0% and YG Entertainment sank 21.3%, likely because of a report that BLACKPINK’s next album has been delayed until January 2026.

Most indexes had an off week. In the U.S., the Nasdaq composite fell 3.0% to 23,004.54, marking its worst week since April. The S&P 500 dropped 1.6% to 6,728.80. The U.K.’s FTSE 100 sank 0.4% to 9,682.57. South Korea’s KOSPI composite index plummeted 3.7% to 3,953.76. China’s Shanghai Composite Index rose 1.1% to 3,997.56.

Created with Datawrapper

Created with Datawrapper

Trending on Billboard

Live Nation reported an 11% increase in total revenue in the third quarter on Tuesday (Nov. 4), the result of continued fan demand for live music and a shift to stadiums from amphitheaters and arenas.

On a call with analysts and investors, CEO Michael Rapino and COO Joe Berchtold discussed the finer points of the results. Although it’s only November, all signs point to more growth in revenue, ticket sales, attendance and sponsorships in 2026. Fan demand isn’t falling back to earth any time soon, and Live Nation has made investments — renovations, new venues and acquisitions — to capture as much of that demand as possible.

Related

Here are some of the highlights from the earnings call and Tuesday’s earnings release.

Stadiums Dominated 2025 and Will Be Big Again in 2026

In the concert business, the venue matters. Live Nation’s owned and operated amphitheaters historically generate better margins than other venues, but in 2025, there have been more stadium shows. “A lot of artists decided not to play arenas and amphitheaters and go for stadiums,” said Rapino. In fact, in the third quarter, Live Nation had 250 fewer amphitheater shows and 120 more stadium shows, according to Berchtold. But because Live Nation operates some of those stadiums — such as Rogers Stadium in Toronto and Estadio GNP in Mexico City — those shows boosted the quarter’s per-fan profitability, Berchtold said.

With the FIFA World Cup taking place in the U.S., Canada and Mexico in the summer of 2026, there have been some concerns that soccer matches would limit stadiums’ availability and put a damper on North America tours. But those fears “haven’t seemed to come to life,” Rapino said, adding that stadiums should have “a very strong year [in 2026].”

Related

Fans Keep Spending

People may be suffering through nagging inflation and feeling economic jitters, but music fans are proving to be a resilient bunch, as per-fan spending at Live Nation’s owned and operated venues rose 8% through October. Part of the growth comes down to offering the right products. Non-alcoholic drink sales were up by 20%, and ready-to-drink options were up, too. The growth can also be attributed to renovations at amphitheaters that created VIP areas with premium food and beverage options.

Amidst the growing importance of VIP options to Live Nation’s business, the company said it’s not seeing any pullback from lower income brackets. “No, we have not seen any of that,” Rapino said when asked by Citi analyst Jason Bazinet if there was evidence of “bimodal” consumer behavior. Many shows for 2026 are already on sale, Rapino noted, and the company saw “no pull-back anywhere.”

More Gains into the Fourth Quarter and 2026

The fourth quarter and 2026 are expected to continue the trends seen in the first three quarters of 2025. Deferred revenue — money collected but not yet recognized as revenue for accounting purposes — is an important metric for assessing demand for upcoming events. Live Nation’s deferred revenue is up big from a year earlier: Event-related deferred revenue of $3.5 billion was up 37% from the prior-year period, and Ticketmaster’s deferred revenue of $231 million was up 30%. In addition, Live Nation says its large venue show pipeline for 2026 is up by double-digits, and ticket sales for concerts in 2026 have already reached 26 million. Sponsorship commitments for 2026 are up double-digits, too, according to the company.

Related

An International Tipping Point is Coming

Fans at international concerts are on track to surpass U.S. fans, the company revealed on Tuesday. In fact, international business is driving Live Nation’s growth. Whereas total fee-bearing gross transaction value (GTV) was up 7%, it rose 16% in international markets. And of the 26.5 million net new tickets from Ticketmaster enterprise clients, 70% came from outside the U.S. Additionally, more than half of the 5 million fans expected to attend concerts at Live Nation’s large (over 3,000 capacity) venues in 2026 will come from international markets.

Confidence in the Federal Antitrust Lawsuit

The U.S. Department of Justice’s lawsuit against Live Nation and Ticketmaster is set to go to trial on March 6. While the company’s latest quarterly SEC filing admits the case “could involve significant monetary costs or penalties,” its executives are publicly confident the lawsuit won’t lead to a nuclear option: namely, breaking up Live Nation and Ticketmaster. Berchtold pointed to the remedies decision in September in the Department of Justice’s case against Google, which aimed to restore competition in the internet search and search advertising markets. The court placed certain remedies on Google — a ban on exclusive distribution of Google Search and Chrome, for example — but didn’t break up the company. To Live Nation, the decision “very much validated our view that the claims in our case can’t lead to a breakup of Live Nation and Ticketmaster even if the DOJ prevails on one claim or another,” said Berchtold.

Trending on Billboard

Live Nation’s revenue grew 11% year over year to a third-quarter record of $8.5 billion, the company announced Tuesday (Nov. 4).

The world’s largest concert promoter and ticketing company continued to benefit from vigorous consumer demand for live music since the touring business came back from the COVID-19 pandemic. Adjusted operating income (AOI) of $1.03 billion was a 14% increase from the prior-year period. Importantly, event-related deferred revenue and Ticketmaster deferred revenue were up 37% and 30%, respectively, suggesting Live Nation is well situated for upcoming quarters.

Related

“Strong fan demand drove another record quarter, as we continue to attract more fans to more shows globally,” CEO Michael Rapino said in a statement. “With these tailwinds, 2026 is off to a strong start with a double-digit increase in our large venue show pipeline and increased sell-through levels for these shows.”

Foreign exchange had a small impact on reported results. In constant currency, revenue was up 9% (compared to 11% as reported) and AOI was up 12% (compared to 14% as reported).

Within the concerts division, record-high stadium show attendance drove revenue up 11% to $7.3 billion and AOI up 8% to $514 million. Live Nation hosted 51 million fans, and attendance was up by double-digits in all major markets. International markets were led by Europe and Mexico, where attendance growth reached double-digits.

Related

Fan demand has undergone explosive growth since the COVID-19 pandemic. Live Nation’s third-quarter revenue of $8.5 billion was 38% greater than the $6.15 billion it generated in the same quarter of 2022. That improvement is dwarfed by the 125% revenue growth the company has experienced since the third quarter of 2019, a time before Live Nation acquired a majority stake in Mexican promoter OCESA in 2021.

Within the Venue Nation segment, Live Nation’s division that owns and operates venues worldwide, fan spending through October rose 8% at amphitheaters and 6% at major global festivals. Investments in renovations have helped some venues improve fan spending. For example, onsite fan spending at Jones Beach in New York was up 35% through October, while onsite spending at Estadio GNP in Mexico City tripled in the first ten months of the year.

At Ticketmaster, Live Nation’s ticketing division, revenue climbed 15% to $798 million while its AOI jumped 21% to $286 million. The improvement came from a combination of more ticket sales and higher average ticket prices: In the quarter, fee-bearing tickets rose 4% to 89 million, while fee-bearing gross transaction value (GTV) rose 12%.

Related

Through the first nine months of 2025, Ticketmaster’s total fee-bearing GTV rose 7% due to a 16% increase in international markets. Primary fee-bearing GTV improved 8% while secondary GTV declined 1% on lower sports activity.

Live Nation’s sponsorships division had record revenue of $443 million, up 13% from the prior-year quarter. With a gross margin percentage of 71%, the highest of the company’s three divisions, sponsorship’s AOI of $313 million, up 14% year over year, bested Ticketmaster on 44% less revenue.

The number of the sponsorships division’s strategic partners rose 14%. New agreements include consumer brands Hollister, Kraft Heinz and Patrón. The division added a multi-year deal with Trips.com in Asia and expanded its partnership with Mastercard to additional markets, including Hong Kong, South Africa and the Middle East.

Related

Live Nation is on pace for a record-setting 2025. Through the first nine months of the year, revenue is up 8% to $18.89 billion and AOI is up 9% to $2.17 billion. The record-setting third quarter is expected to flow into a strong fourth quarter. Arena, theater and club shows will bring the company to full-year attendance of approximately 160 million, which would be a 6% increase from the 151 million fans it saw in 2024. Live Nation expects to deliver double-digit AOI growth for the full year.

Looking ahead to 2026, the company expects continued growth. In addition to growth in deferred revenue — money received for future events — Live Nation expects a double-digit increase in large venue shows in 2026. Average grosses for 2026 concerts are up double-digits on strong sell-through levels.

As demand for concerts appears strong heading into the busy summer months, Live Nation led nearly all music stocks this week by jumping 7.7% to $148.87. On Friday (June 20), the concert gian surpassed $150 per share for the first time since Feb. 25, and its intraday high of $150.81 was roughly $7 below its all-time high of $157.49 set on Feb. 24. Earlier in the week, Goldman Sachs increased its price target on the stock to $162 from $157, implying Live Nation shares have an 8.8% upside from Friday’s closing price.

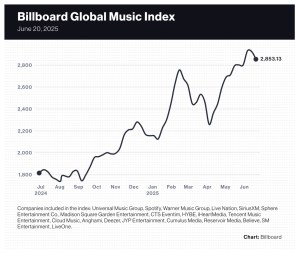

The 20-company Billboard Global Music Index (BGMI), which tracks the value of public music companies, finished the week ended June 20 down 2.4% to 2,853.13, its second consecutive weekly decline after nine straight gains. Despite large single-digit gains by Live Nation, MSG Entertainment and SM Entertainment, the index was pulled down due to losses by its two largest components: Spotify and Universal Music Group (UMG). The week’s decline lowered the BGMI’s year-to-date gain to 34.3%, though it’s still well ahead of the Nasdaq (down 0.9%) and the S&P 500 (up 0.4%) on that metric.

Markets sagged in the latter half of the week as investors expressed concerns about tensions in the Middle East and thepotential impacts on global oil supplies and gas prices. The tech-heavy Nasdaq finished the week up 0.2% to 19,447.41 while the S&P 500 fell 0.2% to 5,976.97. In the U.K., the FTSE 100 dropped 0.9% to 8,774.65. South Korea’s KOSPI composite index jumped 4.4% and China’s SSE Composite Index dipped 0.5%.

Trending on Billboard

New York-based live entertainment company MSG Entertainment rose 5.6% to $38.44, bringing its year-to-date gain to 7.1%. Elsewhere, SM Entertainment stock saw a 4.5% improvement, taking its 2025 gain to 90.4% — the best amongst music stocks save for Netease Cloud Music, which has seen a 111.2% year-to-date gain.

With streaming stocks posting the biggest gains of the year, Spotify shares reached a record high of $728.80 on Wednesday (June 18) but stumbled over the next two days and finished the week down 0.5% to $707.42. That decline took Spotify’s year-to-date gain down to 51.6%.

UMG shares fell 4.2% to 26.73 euros, marking its largest one-week decline since falling 9.2% in the week ended April 4. At the same time, Bernstein restarted coverage of UMG shares this week. Analysts believe it’s a “best in class” music company, which “implies predictability, a capital allocation framework consistent with industry trends, and steady operating leverage,” analysts wrote. Bernstein set a 33 euro ($38.03) price target, implying 23% upside over Friday’s closing price.

Shares of music streaming company LiveOne fell 6.5% on Friday and finished the week down 10.0% after the company released earnings results for its fiscal fourth quarter and year ended March 31. Fiscal fourth-quarter revenue fell 37.6% to $19.3 million due primarily to a decrease in Slacker revenue. For the full year, revenue slipped 3.4% to $114.4 million and adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) fell 18.7% to $8.9 million.

Billboard

Billboard

Billboard

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio