Interview

Page: 5

Chino Moreno is ready to embark on a new arenas tour with his alternative metal band Deftones, starting Tuesday (Feb. 25) at the Moda Center in Portland, Oregon. It’s the California band’s first tour since 2022, and it will share the stage with The Mars Volta and Fleshwater during some spring dates in the U.S.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

At the same time, the Sacramento-based band plans to release new music this year, Moreno tells Billboard Español in Mexico City. “So the plan is, obviously, to have a record sometime around that time [during the tour.] It’s getting very close to being ready, so yeah, we’re excited,” he says of what would be the successor to Ohms (2020).

Almost eight years have passed since Deftones last visited Mexico, where — as in the rest of Latin America — it has a solid fan base. But with his other project, Crosses, Moreno was in Mexico City last December. Here, he and his bandmate, guitarist and producer Shaun Lopez, closed the tour of their album Goodnight, God Bless, I Love U, Delete (2023) at the Pabellón Oeste of the Palacio de los Deportes, after being on the road between 2023 and 2024.

Trending on Billboard

“We made it happen! We were gonna do a full Latin America tour, but it was just gonna be too much time and it was close to the holidays, so we decided we at least have to go to Mexico City,” Moreno says.

It was Crosses’ first show in the capital and it was an incredible experience for him and Lopez, who had never been here before. Lopez, a former member of the now-defunct group Far, created an unexpected close bond with Mexico when he served as a producer of Mexican trio The Warning‘s album Keep Me Fed (2024) — it was thanks to the Villarreal Vélez sisters that the musician obtained his first Latin Grammy nomination last year, for best rock song, as co-author of their song “Qué Más Quieres.”

“When we wrote it, it wasn’t in Spanish,” Lopez tells Billboard Español. “Sometimes when you do songwriting sessions like that, you don’t hear anything for like a year. And usually when you don’t hear anything, you think ‘Oh, they didn’t like it, they didn’t like me’ or whatever, you know? And then the manager hit me up a year later and he said: ‘Can you send me a session for that song?’ He’s like, ‘The good news is the girls are going to convert it to Spanish, which is going to be actually really cool because it’ll be the only song on the album that’s Spanish.’”

In 2025, Moreno will spend much of the year touring with Deftones, so Crosses will have to take a break before returning to the recording studio. “I don’t know how soon it’ll be, but we definitely want to work on more music,” Lopez says. “We enjoy making it and yeah, I just would like to thank everybody for showing interest in our project.”

As Deftones is soon expected to announce tour dates in Mexico, Moreno confirms that the band is considering the possibility of bringing the festival they have been organizing annually since 2020 in San Diego, California — Día de los Deftones, whose name is a clear reference to the popular Mexican tradition Día de Muertos celebrated on Nov. 1-2 — to Mexico.

“We talked about it a lot recently, so it’s definitely in discussions to do so. We would love to do!” Moreno says. “I mean, I can’t promise, but, you know, it’s been growing really great.”

Depending on when you were first introduced to DPR IAN throughout his decade-plus career in entertainment so far, it may be smart to check on how exactly to address the Australian multi-hyphenate.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Born Christian Yu in Sydney, Australia, in 1990, and known by his Korean name Barom, the future star introduced his first moniker by uploading dance videos to YouTube as B Boy B.yu — a nickname thought up by his mother to remind him to always “be you” or, in young Barom’s case, “B yu”). After high school, he embraced an unexpected swerve to debut in the K-pop industry as Rome, the leader of the boy band C-Clown. When the group split, he reclaimed Christian and used +IAN after directing music videos for the likes of BIGBANG’s Taeyang and iKON’s Bobby, before ultimately landing on his DPR IAN stage name as part of he and his Dream Perfect Regime’s independent, creative musical movement.

But for a friendly conversation like the first episode of Billboard’s The Crossover Convo, he says Ian is “perfect.”

“There are so many eras that I’ve been through and pertaining to those eras is where a lot of those names came out,” DPR IAN explains to Billboard. “Having it all laid out like that really puts a lot of things into perspective. I’ve really just been on the run and on the fly, and I haven’t been able to process a lot of these things; it’s been quite the journey.”

With a musical journey that began with a childhood obsession with progressive-music icons like Daft Punk and Moby, embracing British-pop icons like The Beatles and Spice Girls, to diving into new genres on multifaceted projects like vocalizing over icy EDM on “Do or Die” with DPR ARCTIC, while delivering a psychedelic rock experience for “Diamonds + and Pearls” on the Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings soundtrack, that features a diverse roster of superstars like Simu Lu, Anderson .Paak, DJ Snake, Saweetie, Swae Lee, BIBI, 21 Savage, Mark Tuan of GOT7 and many more.

The Shang-Chi soundtrack peaked at No. 160 on the Billboard 200 in 2021, but IAN built upon the chart momentum with his 2022 full-length Moodswings in to Order (peaking at No. 146 on the chart), which was soon surpassed by Dear Insanity EP from 2023 (No. 138).

But IAN says the music’s personal impact on listeners is more important than how much they buy or consume it.

“I’ve never really expected any of that as I was starting this,” he says in reaction to his organic chart rise. “Even if it affects one person and if it’s enough to change one person’s world for the better, that was enough for me.”

For the premiere episode of The Crossover Convo, take a journey through DPR IAN’s music history and look out for the next star to go through their global-pop music journey next month.

Music festivals are more than just concerts — they’re entire worlds where fans lose themselves in the sound, the energy, and the moment. But what happens when an artist doesn’t just play festivals, but makes music that feels like one? With his latest album Festival Season, SAINt JHN delivers an electrifying experience that blurs the line between live spectacle and studio magic.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Led by high-energy singles like “Glitching” and the genre-bending “Poppin,” Festival Season arrived on Friday (Feb. 21) as JHN’s most ambitious project yet. The album fuses elements of house, hip-hop, punk and electronic music, capturing the thrill of a headlining set and the intimacy of a late-night afterparty. Inspired by the euphoric highs and unpredictable chaos of real-life festivals, SAINt set out to craft a project that feels just as immersive as the events that shaped it.

“Festivals are like a different universe,” he tells Billboard just a day before the album’s release. “I wanted to make something that sounds like you’re in the middle of one – something that makes you want to move, scream, and lose yourself in the moment.”

Trending on Billboard

After making waves with While The World Was Burning, SAINt JHN has spent the last few years pushing his sound to new heights. Whether performing on massive stages or collaborating with some of the most forward-thinking artists in music, he’s built a reputation for tearing down genre boundaries and delivering electrifying music. Now, with Festival Season, he’s bringing that same energy straight to the speakers.

Billboard caught up with SAINt JHN to discuss Festival Season, his genre-blurring sound, the electrifying energy of live performances, and how he’s elevating the festival experience on his own terms.Festival Season is your first full project in four years. What inspired the album’s title, and what’s the overarching theme you want listeners to take away?The reason why it’s called Festival Season is because it sounds like you’re at a live SAINt JHN concert.

And if you’ve ever heard any of my music – and even if you haven’t – I’m genre divergent. I’m a bit disrespectful when it comes to genres. I don’t really play to any one particular sport. I just like what I like. I like the sounds of music. So when you hear this collection from top to bottom, from tip to toe, it sounds like you’re in the middle of a festival, and you’re running from stage to stage to hear your favorite artist.

It’s all just me. But the songs change, and the theme changes, and the mood changes. But if you’ve never been to a performance, this sounds like a pocket performance. You can hear crowd interaction, chants. You’re hearing yelling. You’re hearing fans screaming my name.

Because that’s what it’s like to be at a SAINt JHN show. It’s an enormous concert. The mood changes, the theme changes, the sound changes, but the energy never dies. So Festival Season was born from that. I wanted the people who might have been on the other side of the planet, in a place that I’d never been and never visited, to be able to take home a pocket performance from me.

It’s a world where I perform on a stage in front of you. But you get to see some of the things I go through—the emotions, pains, the curiosities, the uncertainties, the doubts—but everything is at a maximum level. Nothing is low. The decibel is on 10-plus the entire time.

With so many different sounds on this project — Afro-fusion, alternative pop, introspective moments — what song do you think will be the breakout hit, and why?I feel like it’d be a stupid response of mine to tell you what I think would be the breakout hit. I don’t know. I’ve never known what people want. I don’t know what people want from me. I don’t know what people want for themselves. I know the way art works in the best format and the best possible thing is you make the thing that you love, and then people decide from that what they love.

It’s like – I was going to say something stupid, like the guy who probably invented the cheeseburger was probably just trying to make a milkshake, and the cheeseburger came out of it, and they were like, “We like that.” So I think maybe some of that will happen. I do have a creeping suspicion. I got a song I think is gonna go crazy.

I think a bunch of them are gonna go crazy. Well, I think for “The Gangsters,” it’s gonna be sort of undeniable, especially when you hear it live—like, when you really see it presented, I think it’d be hard to deny that. But I don’t got no predictions. I don’t want to be the guy at the Super Bowl going, “Yo, this is the team.”

When fans press play on this album, how do you want them to feel? What emotions or experiences do you hope to evoke?I hope when people listen to this collection, I hope they feel bolder than they’ve ever felt. There’s a feeling that you get when you leave a concert, when you leave a festival.

There’s a certain type of energy that you get to take home with you that doesn’t last a long time. For some people, it lasts a couple of days, for some people maybe a couple of weeks, and for some people, it just lasts moments after it. There’s a heightened endorphin, a certain surge of energy, and I want people to get that.

But I want you to be able to press play again and do it again. Usually, you have to venture back to the performance, into a field where you wore an outfit, where you brought a date, where you spent the money on the tickets. Usually, you have to go hunt the thing that you’re looking for. I wanted you to be able to take it home with you so you could restart it every time you felt something that you needed.

Every album has an ideal setting for full immersion. Where do you think Festival Season is best experienced? Is it a car ride, a morning commute, a late-night listen?I think the best place for you to immerse yourself, to hear this, to experience this, is at a tiny rave. That tiny rave could happen in so many different places, right? But your mindset needs to be a “tiny rave.”

It could happen in your bedroom, but you gotta be ready to ruffle up the bedsheets. It could happen in your living room, but you’re gonna have to be ready to spill some coffee, spill some champagne. It could happen in a car ride, but maybe it’d be hard to focus on driving.

It’s an immersive experience, and in order for you to take it in, you gotta be willing to submit to it. This isn’t like a vending machine where you say, “I want Coca-Cola and Sprite.” This isn’t that.This is — show up. I’m gonna make you something really special. This is omakase. This is when you show up, and the chef says, “I’m going to make you something. It’s going to be exceptional. Don’t make any requests. Just be hungry when you get here and be appreciative when you leave here.”

This album also marks a big moment for you—your signing with Roc Nation Distribution. How does this partnership elevate your vision for the next phase of your career?

I think it’s just more freedom. My entire career, my entire purpose in life — the only things I’m looking forward to and the things that I’m hunting, the thing that drives me in the morning and keeps me up at night – is this type of unbridled freedom that only creatives who reach their maximum peak get to feel.

That’s what I look to feel every day. So to be in partnership with people who share a similar vision, who’ve been disruptive from the beginning of their historic run, it just means I’m in league with the right people. I’m just on the right team.

You’ve always pushed boundaries sonically, but Festival Season feels like an expansion of your artistry. How do you think this album reflects your growth since While the World Was Burning?

I always tell a tale from where I’m at at the time. While the World Was Burning, the world was on fire.Collection one was my first collection. So you get to hear the presentation. You get to see exactly where I’m at. I’m centered in the middle of my universe, but I’m telling a story from the seat of the couch, wherever the couch is positioned. Festival Season – you can tell I’m going back on the road. I’m living in my purpose.I’m in my path. My garden has become the stage, and I just want to introduce you to what I’ve been harvesting.

You can hear the maturation in my language. You can hear the maturation in my tone. You can tell I’m not in the same place you left me at, and I think that’s the purpose. That’s an artist’s purpose—to continue growing and evolving.To find new paths. To find new places to venture. To find scarier formats. To find things that are unexplored. It doesn’t seem like I’m tracing myself.

What tends to happen is, when an artist becomes successful, people want them to run the same route—like, “Keep this. Do it again. Do that same lap again. Do it again so I can see it. I didn’t get to see it the way you started the race. Alright, run it again. Alright, cool, cool. We saw it twice. Now do it three times.” But that’s not what artistry is. That’s not what creativity is. Creativity is complex. Creativity wants to continue creating. Creativity designs itself to continue finding new places.

So to be an ultimate, consummate creative, you have to be willing to break through your own glass box that you’ve built. You have to be willing to run the lap backwards, sideways, on your hands. That’s what I’m doing. It might look like the same race, but I’m definitely not sprinting at the same pace.

You chose “Glitching” and “Circles” as your recent singles. Why did you choose those two?

“Circles” is from [my upcoming album] Fake Tears From a Pop Star, and as I was about to roll out Collection Two entirely, I was starting there because Fake Tears From a Pop Star was going to lead.

But I made a pivot. And I think that’s really incredible – when an artist can actually change paths, change course mid-move. I feel like Michael Jordan in the air, about to go for a dunk and turning it into a layup because I saw the block coming. I saw the contender coming, and I was like, “Nope, watch this.”

And the point – the reason why I did that – was because I thought people weren’t ready for it. That’s the truth. “Circles,” for me, is an incredible song. It’s almost like indie rock meets whatever I am naturally. And without me intending to make indie rock music – I’m just doing whatever I feel. I’m just letting my freedom find its own path. But as I was doing that, I was like, “Ah, this isn’t the right timing.”

And I felt this way before. Because I remember how I felt on Collection One, and I trust my own instincts. If you get there before the audience gets there – if you get there long before they get there – your wait to build a foundation is going to be really aggressive. I’d rather build right as they’re showing up.

So I pushed Fake Tears From a Pop Star back a couple months so that I could get the full expression of what needs to happen. As I’m coming back out, running out the gate four years later, I want it to be disruptive. I don’t want it to be harmonious. I don’t want it to be pretty pastels. I want aggressive colors. I want rage. I want dysfunction.

Because I think we need that. I think in the time that we’re in, simple harmony gets overlooked and misunderstood. So we need to fight before we kiss. So that’s why “Circles” led, and that’s why “Glitching” followed “Circles.” Because when I pivoted from Fake Tears, moving on to Festival Season, there was an energy I was looking for. A certain, unfamiliar, progressive energy.

And the strange thing is, my core audience – the people who have been following and loving SAINt JHN since 2018, 2016, 2017 – they want to hear super melodic music. They don’t actually want to hear things that make them dance. The tempo is strange to them. “Glitching” is strange to them. It’s progress that they don’t want. But I know I have to get there before they arrive — because that’s my job.

You’re heading on your Festival Season North American tour next month, and you’re also hitting Coachella. What’s your vision for the live show experience this time around?

Tough question, because I don’t know what my Coachella set is going to be. I don’t know what the stage design is yet. I’m having a thousand conversations. This is my first time really, really collaborating with any degree of people – just considering how else I can see myself.

It almost feels like Alexander McQueen, shifting from creative direction by him – it’s his brand – and someone else stepping in to execute his vision, but with their taste. So I’m considering that. I’m looking at my world in a completely new way. I want to see what somebody else’s perspective on me is.

So I’m entertaining new conversations. I don’t have a complete vision for what that’s going to look like. Because I’ve always satisfied myself on the road by telling my truth. It’s always been loud. But the way I want to present my story now – I’d like it to be theatrical. That’s the truth. I want you to feel a sense of theater with the same sense of journey, passion, commitment, and pride.

Beyond music, you’ve been making moves in fashion with your new clothing line Christian Sex Club and appearing at major fashion weeks. How does your personal style influence your artistry, and vice versa?

I think it’s just another language for me. Style is just language. Sound is just language. Like when you hear a Trinidadian accent, it’s just the melody of the accent that separates it from a Guyanese accent. So style, for me, is just another type of melody.

It’s a visual melody. When the denim hits the leather, and the leather hits the silk, or the fur hits the canvas, and the canvas hits the viscose. By the way, I hate viscose. They inform each other because I get to live in the world that I create.

Like when you see a movie, and you’re listening to the audio from it, you can see the theatrics of it, and you hear the script and the character development. But what really tells you and informs you how to feel is what they look like and what the wardrobe is. So it gives you a different color and dimension.

It’s just another part of it – another part of storytelling for me, another part of the language. Another way to be more dialed in.

You also made your acting debut in The Book of Clarence last year. What was that experience like, and do you see yourself exploring more roles in the future?

Yeah, I’m gonna be doing a lot more acting. I always thought I would. You know what’s funny? I thought I preferred to be behind the camera – and I probably do. But the people who care enough about me are like, “Yo, shut up. Don’t be stupid. Stand in front of the camera. Do the thing that you do incredibly well.”

James Samuels – he is my brother – he directed The Book of Clarence, wrote it, scored it. He did everything you possibly could do. And I’m like, “Yo, I think I want to direct.” He’s like, “Bro, your magic don’t hide.”

So I won’t hide. I intend on doing a lot less hiding. So you’ll see me in more cinematic presentations, even though I just prefer to be the guy that coordinates. Because I think the people who don’t want to be seen, who aren’t looking for attention, can really do their art and execute it at a maximum level. And I think the people who want to dance in front of the lights end up being just performative. And I never wanted to be performative. I really wanted to do the thing I cared about because I really cared about it.

But with all that bulls—t being said – yeah, you are gonna see a lot more acting from me, because it seems to be something that comes naturally to me.

With Festival Season setting the tone for this next chapter, where do you see yourself creatively and personally in the next few years?

Oh, I can see the next 18 months really, really clearly – without giving away anything, My life works best, and my art works best, when I can see 24 months, 36 months – when I can clearly see my vision for the future. And over the course of the last four years, I’ve been building. The next iteration of it is this year.

I really want to put out three collections. That’s the truth. So I’ve been working on the third collection, because Fake Tears from a Pop Star is done. I won’t give away the name of the third collection, but I’m really excited about it – just as excited as I am for Festival Season. And if I can see the third collection this year, that means I can see the first quarter of next year and what touring next summer looks like.

And that gives me an immense amount of clarity. That means I know where I need to be. I feel overconfident that I’m where I need to be. I’m in lockstep.

Miguel Bosé admits that on the first day of rehearsals for his upcoming Importante Tour 2025-2026, he felt terrified. “Oh my God! How was this done? How did one walk on stage?” he thought. But when the music started, his body began to move and glide naturally across the wooden platform to the rhythm of his famous song, “Nena.”

Everything was set for the great return of the pop icon, after an eight-year hiatus. It was time for the world to witness his personal and artistic rebirth.

“I was ready to come back, and suddenly going on tour became the most important thing in my life,” says an visibly excited Bosé to Billboard Español in Mexico City, where he has lived for the past seven years.

Trending on Billboard

“I feel very motivated, with a lot of desire. Oh!” he adds. “You see, I wanted to wait eight years to let all the past drama settle down and be able to rebuild myself physically, spiritually, mentally, emotionally. All that had to be rebuilt.”

Bosé’s last tour was Estaré in 2017, which started in Mexico that February and followed the concept of his last album to date, Bosé: MTV Unplugged (2016), concluding the following year. His last recording was a cumbia version of his classic “Morir de Amor” with Los Ángeles Azules, included in that band’s 2018 album Esto Sí Es Cumbia.

Today, Bosé looks triumphant for having overcome a crisis that shook him on various levels: He partially lost his voice between 2019 and 2023; ended a 26-year relationship with Nacho Palau; suffered the death of his mother, the Italian actress and model Lucía Bosé; and was the victim of an armed robbery at his luxurious home in Mexican City in August 2023.

“When everything that happened happened, and all the problems began to accumulate from all sides, I blamed Bosé. I said, ‘He is to blame’ — ‘You are to blame, bastard, for being who you are. You have destroyed my life.’ So I deconstructed myself like a Lego, and left all the pieces there for eight years,” he said at a press conference following the interview.

The singer of “Aire” and “Si Tú No Vuelves” points out that he had to exercise humility, and decide that the self-punishment had been enough. Therefore, he says that his 2025-2026 Importante Tour will be a “luminous” and “powerful” concert.

“People are going to hear the super hits,” he says, explaining that he had to leave many songs out of the setlist. “I can’t do a six-hour show. It’s not viable.” He details that this tour will consist of several segments like “a collection of paintings” that will depict various characters, stories and landscapes.

Importante Tour will begin its journey on Feb. 27 at the Congress Center in Querétaro, in that state neighboring the capital of Mexico, and will arrive at the National Auditorium in Mexico City on March 14 and 15, before visiting other Mexican cities.

He will continue in June in his native Spain. And, on Oct. 2, he’ll begin the U.S. trek of the tour at The Theater at Madison Square Garden in New York City. In the coming weeks and months, the artist hopes to announce dates for Latin America.

“I look forward for everyone to come and see luminous, a fun show — a journey through time, through the soundtracks of millions of people — to see this beautiful and bold proposal,” he adds.

With more than 30 million albums sold throughout a five-decade career, Bosé is one of the most recognized Latin pop artists globally. On the Billboard charts, he has placed hits like “Nena,” “Morena Mía,” and “Como un Lobo” on Hot Latin Songs and Latin Airplay, and multiple albums in the top 10 of the Top Latin Albums ranking, including Papito, Cardio, and Papitwo.

And his influence extends beyond music. Awarded with accolades such as the Latin Recording Academy 2013 Person of the Year, the Global Gift Humanitarian Award and Telemundo’s El Poder en Ti, as a philanthropist, Bosé is deeply involved in such causes as Patrimonio Indígena Mex, Fundación Lucha Contra el Sida and National Geographic’s Pristine Seas.

Although the 68-year-old artist — who’s also a writer and an actor — says he has many songs he has written over the last few years, he has no plans to share new material anytime soon, because he considers that releasing albums is “not viable” at a time when music has been digitalized.

“I have already built my career,” he says. “I don’t feel like recording anything right now. How do you sell that music? Are there stores, are there supports? How much do you pay? What does it contribute? How much does it give you financially? Nothing, I have no desire for others to take advantage of the new creations, that neither I nor my fans have something tangible — a CD, a cassette.

“[Instead] I’ll sing to the people the first 30 songs they are expecting to hear [on the tour] — because if I don’t, they will slit my throat,” he concludes with a laugh.

“I’ve been bursting at the seams to be able to talk about this stuff,” Chloe Moriondo tells Billboard of her upcoming album, Oyster. The singer-songwriter shifted her aesthetic across her three previous albums, from the ukulele twee on 2018’s Rabbit Hearted. to heartfelt pop-punk on 2021’s Blood Bunny to fuzzed-out, radio-ready melodies on 2022’s SUCKERPUNCH.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Oyster, due out Mar. 28 on Public Consumption/Atlantic Music Group, functions as an amalgamation of those sounds, while also featuring the 22-year-old’s most vulnerable lyrics by far. “This feels like a very special project,” says Moriondo. “I’m nervous, as I always am before releasing things, but especially because this one’s so personal.”

On Wednesday (Feb. 19), Moriondo released the second preview of the album with “Hate It,” a gleefully unhinged pop track with a creeping bass line and an obsessive protagonist (“Wanna wear your body and trade places / Everybody loves you, and I hate it,” Moriondo sings on the chorus). After showcasing a sardonic streak on SUCKERPUNCH, Moriondo lets the dark humor simmer on the track while the listener is urged to hum along.

Trending on Billboard

“It’s one of the only non-aquatic songs off the album,” Moriondo says of “Hate It,” which is surrounded by songs titled “7 Seas,” “Abyss” and “Shoreline” on Oyster. “I did stick very thematically with the ocean, water and all things aquatic in general. But ‘Hate It’ was an oddball, and it just proved to me that I’m going to continue writing murderous pop love songs till I die, I’m pretty sure. And we just couldn’t leave her off the album.”

Moriondo began working on the new album in early 2023, tinkering on songs for weeks at a time in London and Los Angeles, while also processing the worst breakup of her life. Heartbreak, and how to manage its aftereffects, serves as the undercurrent of Oyster, from the mournful piano ballad “Pond” to the reflective bedroom-pop track “Raw” to the breathtaking “Siren Calling,” which offers closure within the final track.

“It was very cathartic to be able to pour out everything that had been going on in my brain and in my life,” Moriondo notes. “It was nerve-wracking, in some ways. I kind of felt like a baby sea turtle — flopping around, confused — for the first couple sessions and the first couple songs. I felt a little bit nervous, but it also felt like an outpouring of pent-up energy and emotion that I was excited to finally be able to release.”

Not only does Oyster represent the cohesive front-to-back listen of Moriondo’s career, but the singer-songwriter says that she wants every aspect of this album campaign to feel part of a whole — and that she became more hands-on with the planning of execution of this rollout than she’s ever been.

“With this album, I’ve just learned how crucial it can be to be as involved as possible creatively, with every facet of the album,” she says. “With an album like Blood Bunny or Rabbit Hearted., I was so young, and I say this as a term of endearment, but I was still very ignorant to a lot of things. I don’t think I poured as much of myself as I could have into a lot of my previous stuff, in terms of the touring, the vinyl packaging, just the life and blood of it. So I think I’m much more connected creatively to this album than I have been.”

After releasing “Shoreline” as the first taste of Oyster last month, Moriondo also announced a spring headlining tour, which kicks off on Apr. 24 in Detroit. She says that ideas for performing these new songs live have dominated her thoughts for months, and she hopes that her shows are as freeing for her fans as making this album proved to be for her.

“The people who come to my shows, whether they’re longtime fans or new fans or boyfriends or parents of fans, can expect to experience a very immersive show,” Moriondo says with a laugh. “A lot of dancing, a lot of potential crying, and something reminiscent of the Jellyfish Jam from Spongebob.”

After dropping a career-spanning live album (2024’s Then And Now) and joining fellow gospel greats Fred Hammond, Yolanda Adams, and The Clark Sisters on Kirk Franklin’s arena-visiting Reunion Tour, Bishop Marvin Sapp made a move few in the gospel world saw coming – releasing an R&B EP just in time for Valentine’s Day (Feb. 14).

Aptly titled If I Was An R&B Singer, the new EP is a notable – but momentary! — genre pivot from one of the most decorated voices in contemporary gospel music. An 11-time Grammy nominee, Sapp has sent a whopping 14 titles to the top 10 of Billboard’s Gospel Albums, including 2007’s Thirsty and 2010’s Here I Am, both of which spent over 20 weeks atop the chart. He’s also earned four chart-toppers on Hot Gospel Songs, led by 2007’s seminal “Never Would Have Made It,” which achieved rare crossover success, reaching No. 14 on Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs and No. 82 on the all-genre Billboard Hot 100. His most recent Gospel Songs chart-topper, 2020’s “Thank You for It All,” was a finalist for top gospel song at the 2021 Billboard Music Awards.

Trending on Billboard

There’s always a kerfuffle when gospel artists cross over to secular music, but Sapp’s new EP arrives under special circumstances. First, people have been wondering what Sapp would sound like on an R&B song for years – it’s one of the ways he grounds the EP’s narrative in the intro. (“I wonder,” muses on-air personality Tyrene “TJ” Jackson on the track, “What it would sound like… an R&B song, or a whole R&B project by Marvin Sapp?”) Second, after a 36-year career that’s garnered him billions of streams and numerous historic achievements, Sapp is in a place where he feels comfortable taking risks – even if he doesn’t think they’re as dicey as others might.

“I sing gospel because that’s my conviction, but don’t think I can’t do what other people do,” he plainly tells Billboard on Valentine’s Day. “I can do it; I just chose a different genre.”

That relaxed freedom and artistic security shines across If I Were An R&B Singer and its quiet storm-inflected, late-‘80s R&B foundation. Featuring writing and production from a close-knit team, led by his son, Marvin Sapp Jr., If I Were an R&B Singer is an entertaining artistic exercise that never sacrifices or compromises the integrity and overall mission of Sapp’s purpose as a singer and artist.

In a lively conversation with Billboard, Marvin Sapp details the making of his new EP, his favorite line dances, the differences in vocal technique across genres, and the R&B he used to croon in the school lunchroom.

When did you finally decide to make an R&B project?

I didn’t sit down and decide to make it; it kinda just fell in my lap. For my whole 36-year career, people have always asked why I haven’t ever sung R&B music or anything of that nature. I always said the reason was that I didn’t feel like it was my assignment. I feel like whenever you do anything musically, there has to be a conviction that’s attached to it.

My son [Marvin Sapp Jr.] said I should make something like [If I Were An R&B Singer], and his good friend Kolten [Perine] produced the record. I decided to put my career in their hands, more or less, because they’re younger and Gen Z, they get it.

You touch on this during the intro, but talk to me a little bit more about your experience with R&B while growing up Baptist.

I grew up in a very traditional church here in Grand Rapids, MI. We didn’t have drums, didn’t have an organ, we had an upright piano, couldn’t rock, couldn’t clap, couldn’t do any of that. When I was a teen, everybody was listening to New Edition because they were a hot group — but I never felt like they could really sing. I was sitting up listening to people like Peabo Bryson, Teddy Pendergrass –who influenced my style in a gospel way – Con Funk Shun and the Dazz Band. These were the groups and singers who shaped me as an artist. That’s who I played around the house. Even though I chose gospel at the age of 10, you know, I was pretty much raised by those individuals.

When you had someone to sing to in the lunchroom, what songs were you singing?

I was singing stuff by the Dazz Band like “Heartbeat” and “I’m So Into You” by Peabo Bryson. My junior year in high school was everything to me because that’s when Between the Sheets by The Isley Brothers came out. I was singing the whole first side of that album. I remember my first major solo at my middle school was “Sparkle” by Cameo. I can count the number of times I’ve sung R&B in my life, maybe 20 times maximum.

This [project] is a one-and-done. I challenge everybody to get it because it’s not like we’re going to do anything else like this again. I just wanted to try it, and I think I did a pretty good job.

How did you develop the specific style of R&B you were going for on this project?

First, I wanted to make sure I didn’t veer too far away from my assignment and my calling. I still want to be the preacher, the teacher, the pastor, etc. I still want to be able to go back to doing what I feel like I do best — and that is singing the Gospel of Jesus. We wanted to make sure that lyrically, it was about love and relationships, but it was clean like a lot of the ‘80s and ‘90s R&B I grew up listening to. I wanted to revisit that particular style and texture.

I also had a conversation with my son and Kolten about making sure that I didn’t jeopardize who I was for the sake of the project. We came up with something that’s current, sensual, but not sexual. And that was the goal.

Who else was involved in making this project and when did that process begin?

It started last year. I built my own recording studio on my property during COVID, so I recorded it there like my last two CDs. The young man who mixed and mastered it, Curtis Lindsey, is actually my [musical director] and has been with me for maybe 17 years. Of course, my publicist Kymberlee [Norsworthy], my son — who co-wrote “Free Fallin” with Kolten and shot the album cover. I’m a very strong believer in using younger gifts that are around you to help you to remain current. It’s very difficult being an artist of 36 years and being blessed to remain relevant – especially when you’re trying to reinvent and introduce yourself at the same time. You have to make sure that you have people around you who really understand the pulse of what’s happening now, and Kolten and Marvin get it.

Did your approach to singing have any notable shifts between gospel and R&B?

Singing R&B is more melodic. In my gospel music, I might be hollering at you one minute, and the next, I’m singing softly and doing certain riffs. This particular record is more of me singing and people being able to sing with me to the hooks. We were trying to make sure it was catchy so we could give people the opportunity to hear me in a totally new light and recognize my versatility. I was able to use my falsetto a little bit, which I’m not able to do as much on the gospel side. I could do it, but once you recognize what people enjoy you doing, you just do that.

How did you come to an understanding of what R&B audiences want to hear in 2025?

I really studied! Of course, I’ve known Tank for years, and I listened to him. But I knew I couldn’t be a Tank. There’s a new young man [named October London] who I really, really love and listen to a whole not. He sounds like a Marvin Gaye type of artist. I literally sat and studied his music, placement and lyrical content. I listened to people like Joe, old-school Dave Hollister, and so many different people, to create some form of gumbo. I took pieces from each of them. The first song, “Listen,” is kind of a throwback to Kem. I got a clear picture of what people enjoy and what they want to listen to.

“Free Fallin” has a bit of a line dance moment. Could we be seeing you hit those moves soon? Do you have a favorite line dance?

I’m still doing the Cupid Shuffle, man. But I’m also learning the dance for [“Boots on the Ground” by 803Fresh]. I know they gonna do it tomorrow night at this event that I’m at. I’ve been on YouTube trying to figure it out. I’ll probably do a [“make your own line dance” challenge] for “Free Fallin” too.

You said this is a “one-and-done” project, but what do the promotional plans look like for the EP? Is a tour in the works?

There aren’t plans for me to tour it, because I don’t think that’s my actual assignment. We’re going to definitely see about getting airplay on R&B radio for “Free Fallin,” because I really think that song’s a vibe, to be perfectly honest. But I haven’t even thought that far. I just wanted to do something that was on my bucket list.

What were those internal conversations with your team like, considering you’re momentarily pivoting to R&B as one of the most highly regarded working artists in contemporary gospel music?

Kymberlee and I sat down and had a real conversation about it — because we were about to hit the road to do the Reunion Tour with Kirk Franklin, Fred Hammond, Yolanda Adams, and The Clark Sisters. This was a big tour, and we had just dropped my new live album. We talked about [how to handle] putting [the R&B project] out, because we were still on the Billboard charts with gospel tracks. We didn’t want to do anything that was going to jeopardize that. After thinking it through and mapping it out, we decided that this shouldn’t be an obstruction to what we do — especially because our target was to release it on Valentine’s Day.

There was definitely concern about backlash, but I think that the body of Christ is extremely mature. There are some that will have negative things to say, but those individuals who really know my heart and my passion understand without question that this is something that I’m doing just because I can. I’m not choosing it as a career.

Do you think there’s something to be said about waiting for the right time to do this project? Would the EP have sounded like this if it came out 10 years ago?

Heck no! Not even close. 10 years ago, I was still striving to be the best artist that I could possibly be. It’s easy for me to do this – and I don’t want this to sound wrong – because I’m accomplished. I can take risks. Even though I don’t honestly feel like this is a major risk, it’s still somewhat of a risk. 10 years ago, I probably wouldn’t even consider doing this. “The Best in Me” was hot, “Never Would Have Made It” was still at the top of the charts and on the R&B/Hip-Hop charts — I had already crossed over! [Laughs.]

Now, I’m focusing on pastoring and opening up another charter school in the DFW metroplex. I’m still making quality gospel music, and I’m still on the Billboard charts. And I’m older, I’m stronger, I’m wiser and I’m better.

We got a live album and a blockbuster tour from you last year. What do you have planned for 2025?

I’ve got a Tiny Desk set later this week, and my church in the DFW metroplex is growing by leaps and bounds. I gotta start a second service. I have two grandchildren now. In this particular season of my life, I’m coasting. It feels really good to be able to pick and choose what you want to do and not have to grind like I did for 20 of the 36 years I’ve been out here.

I’m going to enjoy it because it’s really hard to enjoy the ride while you’re grinding. You miss out on so much and people don’t get it.

At the height of my career, my wife was sick and dying. I missed out on a lot of things because we were fighting for her life, which was more important than anything I was doing outside of my house. Now, some 14-15 years later, I’m in a different place. I’m still able to maintain a level of success and relevance. I’m enjoying every moment of it now because I get the opportunity to view it from a different perspective.

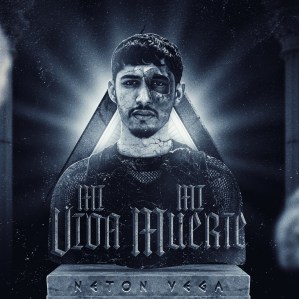

After delivering successful songs as a songwriter to big stars of the new regional Mexican genre — and after making it onto the Billboard charts with hits like “Si No Quieres No” with Luis R. Conriquez, “La Patrulla” with Peso Pluma, and more recently “Loco” — the corrido singer-songwriter Netón Vega presents his debut album, Mi Vida, Mi Muerte.

Released on Friday (Feb. 14) under Josa Records, the 21-track set includes collaborations with Peso Pluma, Luis R Conriquez, Gabito Ballesteros, Oscar Maydon, Victor Mendivil, Chino Pakas, Juanchito, Xavi, Tito Double P, and Aleman. He arrives with “Morena” with Peso Pluma as the focus track, and brings the first single, “Loco,” which earned Vega his fourth top 10 hit on the Hot Latin Songs chart.

“This album is very personal and represents the mixture of all the influences that have marked my career and my life,” Vega tells Billboard Español about this production — which, in addition to corridos tumbados, adds some rap and reggaetón.

Trending on Billboard

Netón Vega (real name: Luis Ernesto Carvajal) was born in La Paz, Baja California Sur, and at the age of 12 went to live in Culiacán, Sinaloa, the birthplace of corridos, where he began writing songs. His first musical references were the traditional regional Mexican artists, such as Grupo Intocable, one of his favorites. Along the way, he delved into corridos tumbados, until he became a hit maker for the great stars of the genre.

“My songs gained momentum and first reached Hassan (Peso Pluma), who recorded ‘La Patrulla,’ ‘Rubicón,’ and ‘La People,’” Vega recalls. “Then they were picked up by Luis R. with ‘Si No Quieres No’ and ‘Chino,’ followed by Tito Double P with ‘El Gabacho,’ and then by Código FN and Gabito Ballesteros, among others.”

Now, at 21, he is releasing his debut album with the collaboration of many of these colleagues — a union to which he credits the growth of this movement. “It makes us stronger,” he notes. “Even though this is a business, we help each other.”

Below, Netón Vega breaks down five essential songs from his debut album Mi Vida, Mi Muerte in his own words. To listen to the album in its entirety, click here.

“Morena” (feat. Peso Pluma)

It is a corrido with classic requinto and a lot of ambiance. This song was born at a live event where I intended to record with Tito Double P, but for one reason or another, I couldn’t do it with him. I wrote this song while I was in a car. Later I showed it to Peso, who liked it from the first moment. At first, the song had a different direction, but it turned out very good. Peso asked me to make it the focus track of my debut album — and of course, I agreed.

“CDN” (feat. Luis R. Conriquez)

It’s a corrido that carries the hallmark I’ve always loved, with classic guitar picking, flawlessly executed. Honestly, this song was created because I knew it would be perfect for Luis R. Conriquez, and it turned out just right. It’s exactly the style that he and I share — and from the moment we made it, we knew it was going to be a hit. It’s one of those corridos that feels authentic, with real power.

“Chiquitita” (feat. Tito Double P)

Initially, “Chiquitita” was meant for Tito’s album. I sent it to him to record quickly because it needed to be submitted. However, in the end, I asked for it back and decided to keep it for my own album because I felt it needed a change, to have my own stamp on it. Honestly, I really liked how it turned out. “Chiquita bonita, déjate querer” (Pretty little one, let yourself be loved), that phrase is key in the song. It’s a romantic corrido that brings that touch of emotion with a distinctly marked requinto.

“Me Ha Costado” (feat. Alemán & Víctor Mendivil)

“Me Ha Costado” is a track with Alemán that came together in a crazy way. I remember sending him a video with the idea, and he liked it so much that he stopped eating and went straight to the studio. I mean, he really liked it — one of those times when you say, “This is a hit!” Then I invited Víctor Mendivil, and honestly, he did a great job on it. This song talks about effort, about everything it has taken for me to be here because I’ve been working since I was a kid, and everyone knows that. It’s a trap song with a really good beat.

“Cuando Me Ocupes” (feat. Xavi)

“Cuando Me Ocupes” came out very naturally, and was the last one to be recorded. With Xavi, we made two tracks, one for him and one for me. Everything was put together in two intense days in Guadalajara. Josa, my manager, arranged everything, and we got down to recording. It’s a love corrido, but with that style that makes it feel real. It’s one of those songs that brings a lot of emotion.

Netón Vega

Josa Records

Everyone’s curious about the teens and twenty-somethings who make up Gen Z. How do they interact with each other? Do they even dance in the clubs anymore? What’s the dating world like for them? With his new Wonderlove album, rising ATL-bred R&B singer Chase Shakur may have a few answers.

Introduced by singles like “Focus on Me” and the TyFontaine-assisted “Fairytailes in Midtown,” Wonderlove arrived on Friday (Feb. 7) as Shakur’s debut studio album — and his second full-length project under Def Jam. His new record charts its moody, introspective emotional odyssey through a soundscape that amalgamates gospel, soul, dancehall, Miami bass, trap, Afrobeats and more. Inspired by the surrealist world of Quentin Tarantino’s Oscar-winning Pulp Fiction and the globe-traversing DJ sets of his closest friends, Shakur sought to make an album that truly examined what love looks like for Gen Z in 2025.

“Sometimes we look at love kinda surface-level,” he tells Billboard just two days before the album drops. “We look at love for what we can get from it instead of adding to one another. I wanted to make a body of work that feels like a hug.”

Trending on Billboard

After bursting onto the scene with his 2022 debut project, It’ll Be Fine, Shakur spent the next two years pumping out music and hitting the showcase circuit in 2023. Last summer, he toured the globe alongside The Kid LAROI on the Grammy nominee’s The First Time tour.

A rapper-turned-singer with deep reverence for the roots of traditional R&B, Shakur displays tremendous growth across his debut album, which he began recording while touring London in December 2023 and finished during The Kid LAROI’s tour. On “Fairytales,” he slickly flips Sexyy Red’s raucous “Get It Sexyy” into a brooding, sensuous ballad, and he even buried a trap-inflected hidden track on the back half of the album’s closer, “A Song for Her.”

Billboard caught up with Chase Shakur about Wonderlove, deepening his film knowledge, his forthcoming tour, and honoring his family legacy through music.

Do you have a favorite moment from the creative process for this album?

Just living in L.A. for three months and being hella disciplined. I was on a meal prep routine and going to the gym; we only wore black clothes so we could lock in and not be distracted by anything else.

How do you feel you’ve grown as an artist and as a person since your debut?

I have a better understanding of what I’m trying to do with my career and my art. I’m learning maturity in my music.

What are some elements that you would consider immature in your older music?

Being scared a girl I’m talking to might hear something that I say [on a record] and crash out on me. I used to be nervous about that, but now I’m like “F–k that s—t.”

How do you think your growth manifests itself on Wonderlove specifically?

I’m a lot more fearless on this project. I had a session with No I.D. and Raphael Saadiq, and No I.D. gave a n—a the illest advice about not giving a f—k about perception. Just tell your story and bring those special nuances. I was nervous as f—k because they’re my inspirations, but they’re mad cool. In between recording, I would walk out into the lobby and get to hear how they did “How Does It Feel” with D’Angelo. We [as up-and-coming artists] overthink it. Listening to them talk about how the song was made because D’Angelo was looking for weed… we overthink a lot of the time!

You dropped your first two projects in back-to-back years. Why’d you take a bit more time with this one?

I wanted to make a story that people could understand. This was my first time doing something that had elements of surrealism, but I still wanted to keep it rough at the same time. When I was on tour [with The Kid LAROI], I was watching a bunch of movies that I hadn’t seen but everybody else had seen. I watched Pulp Fiction for the first time, and it felt real but like… your friend not gonna tell you no s—t like that, you know what I’m saying? [Laughs]. I’m trying to blend that world with my production and lyrics and make a full body of work, not just one song.

What does the term “wonderlove” mean and when did you know that was the title?

I came up with the title after coming home from tour and going to my grandma’s house. I grew up in a house with eight people, split between the women in the family and the men in the family. In Black households, we all have that picture that everybody knows. I was flipping through the photo album with my grandma, and there’s a picture of her and my grandpa. I never met my grandpa, but my grandma used to always tell me about the love they had for each other and the type of man he was. In her telling me that, I wanted to make something that was the opposite of what people are talking about right now.

Other than Pulp Fiction, what else were you consuming while making Wonderlove?

I listened to a lot of stuff. Reggae, a lot of Afrobeats, R&B of course. I watched Belly and Paid in Full – I know, I’m supposed to have been seen that shit – and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. I’ve just been studying film, man; I’m trying to make my visuals stand out with those elements of surrealism.

I think when people see me – I don’t know what they think really – but I feel like there’s an element of mystique. And with mystique, there’s a little bit of magic.

How did the Smino collaboration come together?

I was on The Kid LAROI’s tour, and he sent his verse a month before I left Baltimore. I randomly got it on the bus, and I was like, “What the f—k!” In my personal opinion, we got the best Smino verse in a minute. The video for that is gonna be wild too, so I’m excited. There’s always an element of unpredictability; I was playing his s—t months before that particular exchange even transpired. I like having a blend of vocals or a different contrast when I collaborate with people. I also want to step outside [my comfort zone] and mix genres.

You got a track on here called “Sex N Sade.” What’s your favorite Sade song?

“Soldier of Love!”

You end the album with a slightly more traditional piano-led ballad. How do you keep traditional R&B present in your style?

For this album, I would say the [main traditional] element was gospel music. With “2ofUs,” my mentor, Ari PenSmith, really helped me understand how to use my voice in a way that still has what I grew up on: the gospel and blues elements of traditional R&B.

In the past, I undermined my vocal evolution. I listened to the last project I dropped a couple of days ago, and vocally, I’ve made a 180 [degree turn]. When you listen to the first joint and then listen to me now, I’m much more confident and open.

“Undercover Angel” is a sick mix of Miami bass and dancehall. What was that studio session like?

Everybody thought I was crazy when I said [that was gonna work], ain’t gon lie. That’s slick how it goes a lot of the time, and then it works! A lot of my friends are DJs, and I go to their events and listen to their mashups and s—t. I record them when they blend Afrobeats and all that, I think it’s cool. I don’t know what made me want to have those dancehall elements, but I just wanted people to have fun. People be like, “What the f—k?” when they hear it – especially when the bass drops.

“Face” also has some overt house influences. Do you plan on exploring dance music further on future projects?

I try everything in the studio. I have rock songs, I got jazz songs, I got country songs, everything. When I tried making dance songs for the first time, it wasn’t cause I could dance. I can’t f—king dance. When I started working on this album, I was going to a lot of clubs where it wasn’t section culture. I’m in Atlanta, so I’m pulling up on R&B nights and seeing it’s possible for us to have fun and be cool at the same time. That’s what inspired me to make and throw out more dance songs.

How have you grown personally and professionally since signing to Def Jam?

I learned that everything is a choice. Somebody told me that, at this stage, you can choose to do three shows a night or do one show and go home. But it’s all up to you to put in 10,000 hours — not just with recording, but performing and being an all-around artist too. I know I want to be an artist with longevity, and being on Def Jam is teaching me ways to be patient with that.

Do you have any tour plans?

It’s gonna be a family affair, man. I’m excited about the tour. I got SWAVAY opening up and my family with me. Got a couple of shows being opened up by artists from the [Forever N September] collective. We’re coming with a stage that tells a story. It’s my first time doing some stage design, so this is a real learning process. I’m most excited to perform “Say That You Will.”

What happens when Caribbean tropical rhythms meet the world of astrology, feminine energy, and spirituality? A colorful supergroup called ASTROPICAL is born.

The new band group created by Bomba Estéreo and Rawayana — two of the most beloved contemporary bands from Colombia and Venezuela, respectively — took the world by surprise just a week ago when it released the track “Me Pasa (Piscis)” while making the announcement that the song was just the first single of an entire project that was soon to come.

On Thursday (Feb. 6), Billboard Español can announce that the 12-track album — one for each zodiac sign — will be released on March 7. Or as Li Saumet from Bomba Estéreo says: “Before Mercury goes retrograde.”

Trending on Billboard

The LP, also titled ASTROPICAL, includes the songs “Brinca (Acuario),” “Siento (Virgo),” “Otro Nivel (Capricornio),” “Una Noche en Caracas (Tauro),” “Happy (Libra),” “Calentita (Aries),” “El Lobo (Cáncer),” “Llegó El Verano (Sagitario),” “Quién Me Mandó (Géminis)” and “Corazón Adentro (Escorpio)” — in addition to “Me Pasa (Piscis)” and the upcoming single “Fogata (Leo),” to be released on Feb. 20, and which Saumet feels “is going to be one of the most transcendental songs of this album.”

And they have already started scheduling live performances, beginning with the Vive Latino festival in Mexico City, where they are set to play on Sunday, March 16, and the Estéreo Picnic festival in Bogotá, where they will perform on Saturday, March 29.

In an interview with Billboard Español, Saumet and Beto Montenegro from Rawayana talked about zodiac signs, feminine energy, and the musical “child” that was born from their union.

For starters, how did this collaboration come about?

Saumet: I have an intuition, and I visualized. A little voice told me, “The time has come to make the song with Rawayana.” And I woke up and said, “I’m going to call Beto and tell him.” Since my team is close to his team as well, I asked for his phone number. And Beto got me right away and sent a track.

Montenegro: I told her yes, of course, but let’s book two days in the studio instead of one in case the first day doesn’t go so well.

Beto, were you already a fan of Bomba Estéreo?

Montenegro: I have loved what Bomba has done in their career; they are an icon and musically speaking, they are exceptional. And something was happening to me — like I was understanding the power of manifestation and discipline and work. When Li contacted me, it was one of those things. I was watching Bomba Estéreo at a sunset on a beach in Chile, in Pichilemu. We were the four Rawayanas watching Bomba and I told the guys it felt like: “Wow! It seems like this is what’s going to happen now.” And then Li contacts me a year later. We got together in the studio and in two days three songs came out, so from there we agreed: “Let’s make an EP, but let’s go to your house in Santa Marta.”

How was that process, and why is it called Astropical?

Montenegro: Li is so wonderful, full of flowers and light and spirituality. And throughout the process, the presence of the [zodiac] signs was there. It was like: “You are so Aquarius, you are so Capricorn”… her and her friends. So I tell her, “We have to do something that has to do with the stars,” because we had the whole process with this theme. And I tell her, “Honestly, I don’t follow astrology much, but I find it very interesting.” And it didn’t take long for her to say, “How about Astropical?” And I said, “Wow!”

When did all this happen?

Saumet: In January last year. I mean, a year — we literally had a child. In January he impregnated me, or I impregnated him, because from here you don’t know who impregnated who. And now the kid is coming out. And it’s nice because I’m lucky enough to coincide with people with whom I complement with musically and things come out, always trusting also in my intuition, which is accurate in the sense that I can complement something or contribute something nice and organically. I feel it has been incredible to work with Beto and the guys, because their energy is wonderful. He is Aquarius! I mean, my husband is Aquarius. Aquarians are beings that move me a lot because I am Capricorn and I am earth, I am always working and I have many ideas. But he takes those ideas of mine and complements them. When that comes together, it creates a wonderful mix.

Add to that that my birthday (Jan. 18) and his birthday (Jan. 21) are close, so there are the signs. Then the planets align. I mean, it’s all very crazy, even to me as someone who believes in that. I feel that everything that is happening is organic, we haven’t planned it. Of course, there is a general plan, because fortunately, we are very clear about what we want and we have good ideas, but it has been very organic and very nice. It has been like a complement not only vocally, but also lyrically. I feel that the whole image and the whole concept has been complementary and it has been nice because he says he has learned a lot from me, but I have learned a lot from him too.

How do you complement each other?

Saumet: Well, Beto is a millennial, and I am timeless. [Laughs.] I am very open to changes, and he is very aware of what is happening. That was one of the things that attracted me a lot to this new process with Rawa, it inspired me like, wow! Because artists are always reinventing themselves, it’s not something you do or you don’t — you have to do it as an artist. But what people from younger generations have a lot, more and more, is that they reinvent themselves all the time: One day they are one thing or the other o everything at the same time.

They don’t let themselves be typecast…

Saumet: No, they don’t. And that has always caught my attention, because in a way, when I started making music, I did that. I made music that no one else was making and it was weird and people said, “What is this? Or I don’t know, a haircut or something. I mean, very atypical things at that time, because I have always been very atypical and I feel that he has a very good intuition at the work level and he is also very logical, he has like a very masculine energy, which is cool. The Aquarian is always a being who is between heaven and earth, that is, someone who is a bit made to do great things. And well, I am very spiritual, but also very hardworking, very disciplined, so I feel that we complement each other in that: intuition with thought.

What have they learned from each other?

Saumet: I’ve learned to listen, to trust. I’ve learned a lot! From the way he treats work, which I always had at a certain level and now I see from a different perspective, like interacting more. I don’t know how to explain it. Something I’ve seen from Beto in these months that I have been with him, is that he opens up a lot, and I have always opened up a bit but closed, very much respecting my space. I feel that it shouldn’t be like that, that there should be a balance.

I feel that this interaction makes things move forward as well, because it’s always an exchange of energy, and he is very good at that. He takes the leadership and he goes out and he makes it happen. I’m a bit shyer sometimes. When I’m on stage it’s another thing, but in terms of — I don’t want to say the word, lobbying, I’ve learned from him that when you open up, other things open up for you as well.

Montenegro: What happened to me, in the moment I am personally living now, is that the arrival of Li has been like an encounter with spirituality. It’s like a rain of flowers mixed with a strong feminine presence. I mean, I feel super feminine in this process. I have been working with men for many years, and working with a team of girls, where we are debating things or making decisions, I am delighted.

I think God is sending Li to me so I can connect with that, with spirituality. In the creative process, I tell my team: “Here the boss is Li. We are here; let the feminine power take over us.” And I really like that she is a person who has managed to design a life full of colors. She says she is reserved, but she shows a very interesting openness. And I think maybe the mix works because of that. I also think, when you hear her voice, it’s an explosive thing and maybe my voice is a bit sweeter. You can feel that in terms of sound.

Any fun anecdotes from this last year working together?

Montenegro: Well, our birthdays celebration was crazy.

Saumet: Ahhh, it was great! We went to San Sebastián in Puerto Rico, where we were actually doing a listening of the album, and we celebrated every day.

Montenegro: It was like a That was like a fair. We danced… The cultural interaction has been very interesting, but I feel that if we weren’t singers, Li [still] would be my friend. We like similar things. I mean, we celebrated our birthdays and I felt like when parents bring two little kids together to share a birthday, with the same friends. Our friends [ours and hers] are all alike. We are different nationalities, but we are all the same specimen.

Saumet: It was lovely. We did karaoke, salsa lessons. We had a great time.

What can we expect next?

Saumet: A song that I really like, called “Fogata (Leo),” which I feel is going to be one of the most transcendental songs of this album. It comes out on Feb. 20. It also has a beautiful video. I feel that when we made it — I don’t remember if I was on mushrooms or not, I don’t think so. But I remember that it was something magical; that song generated a super nice energy for me.

What is it about?

Montenegro: Well, “Fogata” is like a request of what we want for when we are not around anymore.

And when is the full album due?

Montenegro: March 7th.

Saumet: Before Mercury goes retrograde!

La Original Banda El Limón de Salvador Lizárraga, one of the longest-running Sinaloan bands in the genre, is celebrating its 60th anniversary and is preparing to celebrate throughout 2025.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

“I am happy to announce that Alex Lora, frontman of El Tri, has joined our celebration with one of his songs, “La Raza Más Chida,” which we will unveil in due time,” reveals Juan Lizárraga, grandson of the group’s founder and current music producer, in an interview with Billboard Español. “There are several guests for duets that we will be announcing in the near future.

“We would like to include some of the vocalists who have been in the band, like Julio Preciado,” continues Lizárraga, referring to the first official singer not only of La Original Banda El Limón but of any banda music of its kind.

Trending on Billboard

La Original Banda El Limón was formed in 1965 in a small town in Sinaloa called El Limón de los Peraza, from which it took its name. Following in the footsteps of its predecessor, Banda El Recodo de Don Cruz Lizárraga, it began as a wind band and, already with a defined style and an earned reputation, served as accompaniment for great stars such as Lola Beltrán, José Alfredo Jiménez and Antonio Aguilar. In 1990 they released their first album, Puro Mazatlán, with which they innovated by putting their own vocalist in a Sinaloa band for the first time.

Since then, the band has released more than 50 albums, 10 of which have appeared on Billboard‘s Top Latin Albums chart and seven on the Regional Mexican Albums chart. The group has also placed 33 songs in Regional Mexican Airplay, reaching No. 1 with “Al Menos” (2010) and “Di Que Regresarás” (2011), among other achievements. Banda El Limón has received multiple awards such as Latin Grammys for best banda album, twice, for Soy Tu Maestro (2010) and La Original y Sus Boleros De Amor (2013), as well as the Billboard Mexican Music Award for Excellence in Regional Mexican Music in 2012.

On Jan. 29, the group received recognition from the Promotores Unidos USA association in Las Vegas, kicking off his anniversary celebrations.

Today, Don Salvador Lizarraga’s grandchildren, who call him papá, carry on his legacy since his passing in 2021. One of them, producer Juan Lizárraga, talks with Billboard Español about their accomplishments, their upcoming plans and the possibility of one day seeing La Original play alongside music peers like Banda El Recodo and La Arrolladora Banda El Limón.

How great is the responsibility to remain relevant after six decades?

I would start by saying that I am very excited. Time goes by very fast; ten years ago we were celebrating our 50th anniversary with a huge concert at the Zócalo in Mexico City, something that marked our history. The legacy of my papá Salvador is something that must be dignified, something that we must work hard on. My brother Carlos, my brother Andrey, Francisco and I learned from him as a professional, but also as the great gentleman he was. This celebration is a dream come true for my dad, even though he is no longer here, and for us who are carrying on his legacy.

Characters like Don Cruz Lizárraga (from Banda El Recodo) and Don Salvador Lizárraga built a very important part in the history of regional Mexican music. Did your father realize that?

My dad used to tell us that he couldn’t imagine what was going to happen to his band. At the time, the only thing he thought about was bringing home the bread. People like him and Don Cruz Lizárraga loved music and in it they found their family’s livelihood. They were not looking for success; they just enjoyed what they did. It has been a great journey in which many characters have left their lives to achieve that the bands are positioned as an important part of Mexican culture.

What is it that keeps Sinaloa’s bands alive?

There are songs that are 30 years old and are still hits. That is what makes a group great, that makes the difference. It is with music that we really transcend and remain relevant. As long as there are singers and musicians who love the band, it will never stop and will continue to be strong. Banda El Recodo and La Original Banda El Limón are recognized for their longevity, but we cannot overlook what Banda MS has done. In twenty years, they have achieved what it took others twice as long. La Arrolladora also had its golden age. Banda Los Recoditos too. In short, there are many that continue to dignify regional Mexican music.

Fashions come and go, but what is well cemented continues. It is like when a hurricane passes and does not knock down a palm tree; it will shake it, it will bend it, but it is well planted and will not knock it down. Banda sinaloense music already has a hard-earned place.

What do you have planned to celebrate these 60 years?

I am happy to announce that Alex Lora, frontman of El Tri, has joined our celebration with one of his songs, which we will unveil in due time. He is delighted with how the arrangements turned out because we took care of the two essences, we achieved a point of balance. At the end of the day, we are enhancing Mexican music. We are focused on making collaborations with artists that are joining us. It’s not about doing songs by La Original Banda El Limón; we did that not too long ago. We want the guest to choose the song, and most importantly, we want them to enjoy banda music. As for a party, we also have it in mind and we are working on it.

Throughout your history you have had some great collaborations, is there one you remember in particular?

Fortunately there are several, with very important artists like Jenni Rivera, Juanes and Becky G, but one that was definitely a big challenge was to be part of the tribute to Caifanes with “No Dejes Que.” Making it sound good with a band and making them like it was not easy, but they were very satisfied. All those moments make us feel happy and proud of our genre.

Will there be a time when we can see something together with Banda El Recodo and La Arrolladora?

With whoever, we are open. I believe that all our colleagues should have the idea of making our music continue to transcend, to make a team. I believe that there are no egos or envy, what we have are matters of negotiation. My dad used to say and he said it well: “Credits are not earned on a piece of paper or in an advertisement, they are earned on stage.” At least for La Original Banda El Limón, opening or closing is the least of it. We are very happy that Banda El Recodo and La Arrolladora are touring together. We wish that could be extended. There are many things that can be achieved if we all come together, to make a great team so that we can bring a strong musical history to the people.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio