Interview

Page: 3

Ryan Coogler’s Sinners – a Southern Gothic vampire-musical-period epic led by Michael B. Jordan – is an irrefutable juggernaut. With thousands of moviegoers clamoring for prized IMAX 70mm tickets and endless discourse across social media, Sinners is perhaps 2025’s first genuine cultural phenomenon – and the haunting Raphael Saadiq-penned “I Lied to You” sits at the center of it all.

Performed by breakout star Miles Caton in a pivotal – and instantly viral — scene tracing the history and legacy of Black music, “I Lied to You” is, at its core, and simple acoustic guitar-and-vocal track that effortlessly conjures the spirit of 1930s Delta blues. Already a leading contender for 2026’s best original song Oscar, “I Lied to You” marks the union of Saadiq, a Grammy-winning R&B maestro and founding member of Tony! Toni! Toné!, and two-time Oscar-winning composer and longtime Coogler and Childish Gambino collaborator Ludwig Göransson. Built around a refrain Saadiq, now 58, first came up with when he was around 19 years old, the song’s journey also mirrors the timelessness of blues songwriting.

Trending on Billboard

Saadiq — who’s no stranger to scoring films, having contributed music to everything from Soul Food and Baby Boy to Empire and Love & Basketball – could pick up his second career Oscar nod for “I Lied to You.” In 2018, he earned a best original song nomination alongside Mary J. Blige and Taura Stinson for Mudbound’s “Might River,” bringing him one step closer to an EGOT. In addition to a 2021 Emmy nod, Saadiq has collected three Grammys, including a recent win for album of the year thanks to his work on Beyoncé’s culture-quaking Cowboy Carter LP, the latest addition to a catalog that champions the breadth and depth of Black music.

“We’re the ones chosen to raise the bar – and the bar has been pretty low in a lot of different areas,” he tells Billboard of artists like himself, Beyoncé and Coogler. “Some choose to not let the bar be that low, and that’s what happened. When somebody calls your name, you go to be ready.”

For an artist and musicologist like Saadiq, all of that hardware pales in comparison to connecting with the fans who have sustained his nearly four-decade career. At the top of the year, he launched an exclusive vinyl club for fans to peruse his legendary vault, access exclusive artwork, and enjoy quarterly releases of old and new work. On May 31, the esteemed multihyphenate will launch his No Bandwidth one-man show at New York’s iconic Apollo Theater, his first totally solo trek.

In a wide-ranging conversation with Billboard, Raphael Saadiq talks working on Sinners and Cowboy Carter, drawing inspiration from Mike Tyson, and where he hears the blues today.

When did Ryan Coogler first approach you to contribute a song to the film?

I think maybe a week before he went to shoot it in New Orleans [in April 2024]. He reached out to me and gave me the full scope of what the movie was about. He told me that his uncle was a blues guy and explained how the church had a problem with blues players. There was a separation. But it wasn’t that the blues players didn’t believe in God, it’s just that the blues was their church.

It was right up my alley because that’s exactly how I grew up. Playing R&B music, I was told that I was playing the devil’s music, too, so it made sense to me.

What was your initial reaction to the plot?

I don’t even know if I really understood the plot completely. There’s really no way to understand it by someone telling you. You need to see it. He gave me some guidelines, and I took it from there. I was used to doing that because I worked with John Singleton a lot on some pieces – he was the one who told me I should score film. John would tell me what was happening in the scene, and that was really good practice because I didn’t really have enough time [to write “I Lied to You”]. The movie wasn’t shot. I didn’t hear [the song] until the movie came out.

What was most unique about the Sinners process?

The passion of the story. I have so many stories of Howlin’ Wolf, O.V. Wright, Bobby “Blue” Bland and B.B. King playing in my house growing up. This process really brought me back to my Baptist church roots. Even the humming that I’m doing on the track – I got that from Union Baptist Church. We call it devotion-type singing.

Without seeing any of the dailies, I knew [that humming] would fit. I didn’t know how well it would fit, but it was really some kind of ancestral-pilgrimage-storm. And [Miles Caton’s] voice… oh my God! That voice is crazy. I never heard his voice, so I just wrote the song how I would sing the blues.

They wanted me to put my demo out as well, but I felt like the movie is so amazing that when people go to DSPs – they should only hear Miles. I love his voice.

Where do you think Sinners fits in the legacy of Black music films?

I would say it could match The Color Purple. I would have said Superfly, but Curtis Mayfield had way too much music in there. But the way Ryan likes to work, one day, I know he’ll make a very musical shoutout to the world, like what Curtis Mayfield did with Superfly. I feel like that’s on the horizon.

Walk me through the session in which you and Ludwig Göransson wrote “I Lied to You.” How did you capture the essence of 30s Delta blues despite using modern tech?

In a modern time where people have a lot of outboard gear and different compressors, it doesn’t matter what you have, it’s really in the fingers. It’s in the hands. It’s in the mind of the person that’s doing it. I was playing an acoustic guitar in Ludwig’s studio, and we jammed for a second. I wrote the lyrics on the spot right there, and recorded everything that night. And then Ludwig scored the hell out of it [for the Black music history montage] – I wasn’t there for that.

What musical touchstones from your career and catalog did you pull from to write this song?

I’ve always had blues ideas, but I never thought I had the voice for blues. I would just sit around and make blues hooks because blues hooks are the best hooks ever. When I was younger and struggling to tell my girlfriend the truth about something, I said, “You know what would make a good blues song? They say the truth hurts, so I lied to you.” I’ve always had that.

I had another one when I was a kid; my mom asked me to do some work, and I remember thinking, “I’m so young, with the way she’s treating me, I might as well grow a beard.” [Laughs]. I never told her that, but I sang it in my room.

For [“I Lied to You”], I thought Sammie’s character was lying to his dad, but he wasn’t really doing that. He was telling him the truth. But [at the time], I thought he was lying, so that’s why I landed on those lines.

What makes a real blues voice?

You hear how Miles talks? He sound like somebody grandpa. He got that thing; he got that it factor. You gotta sound gravelly. I have to try to sing a blues song. He just gotta open up his mouth. My dad would tell me all the time — that I had to change my tone if I was gonna sing the blues. But I’m a tenor dude, I got a pretty voice. I just don’t think that I have a blues voice. I’ve gotten raspier and know how to do it now, but when I was in Tony! Toni! Toné! in the 90s – and it worked, I’m not complaining! — [my voice] was cute. Once I did my The Way I See It album, I learned how to sing and act like David Ruffin. Never had his voice, but I could mimic things. But this kid [Miles] doesn’t mimic nothing! That sound just comes out.

What was it like when you finally saw that key scene?

Honestly, the second time I saw it, I closed my eyes, and I prayed. I saw it for the first time with Ryan in IMAX at the premiere in Oakland. But the second time, I understood the movie even more. I hadn’t been back in Oakland since my brother [D’Wayne Wiggins] passed about two or three weeks [before the premiere]. I had a whole lot in my mind, and I was just very grateful and thankful.

The music from all those time periods – from the ‘30s to Parliament-Funkadelic – is all the things I grew up with. I’m not old enough to have been there with John Lee Hooker, but my father was born in 1929 and he’s from Tyler, Texas. My mother’s from Monroe and Shreveport, Louisiana. The gospel quartets I played in as a child, all those men — they all picked cotton. That was their job. So, I’m not removed; I grew up in a house with people who did that. When the movie opens up? That was probably my father. To be able to contribute music to a piece like that… it just came out.

Did you also feel a link between Remmick’s character and predatory record execs?

Definitely. When he said, “I want your stories…” Wow… We all make music — Black, white, Asian, etc. A lot of people are really good at it; it’s a universal thing. I know some bad players in every genre, singing, drumming, bass guitar, arranging, anything. The gift is not given to just one nationality, it’s given to all.

But the one in Blues, we own it. The soul s—t, we own it. Nobody got us with that one. This is ours. I know this because in my car I’ll listen to everything from classical to classic rock – and I still come back to the soul station or some blues station. I think the world understands that about Black culture and Black music. It’s not like they don’t know. We put spice in the game.

That bluesy storytelling is also present on “16 Carriages” and “Bodyguard,” two Cowboy Carter tracks you worked on. What was that moment like when they called the album’s name for best country album and album of the year?

I’m not big on Grammys or awards, but I was that day! It felt really good. I had a nice glass of champagne and a really good time just being there. Beyoncé works so hard, it’s just crazy; when somebody works that hard, they deserve it all. I really like to work with people who can work harder than me and match my work style – and I work really hard! It’s great to see someone who has accomplished so much already – who you would think Grammys don’t mean that much to, but I’m sure they do – continue to be driven by something that’s definitely not awards. It’s something deeper. I was honored to be a part of it.

I don’t really remember too much about working on the record, because we were just having a good time. The only thing I remember is when I played the guitar solo on “Bodyguard.” I don’t normally do guitar solos; I’d probably just call my boy Eric Gales, who plays guitar all over [Sinners]. We were going to have an eight-bar solo, and Beyoncé was like, “Nah, you can go 16.” We were in a time crunch, and I didn’t have time to call somebody, so I had to go in the room and play the solo, which I could already hear in my head. I loved that challenge. I always love passing work to great people, but this time I had to jump on it. It was fun cutting a Dirty Mind-era Prince guitar solo.

Sinners and Cowboy Carter are two landmark works that, at times, feel in conversation with each other. How does it feel to be able to work on these projects and intertwine your own legacy with theirs?

I love the storytelling on both Cowboy Carter and Sinners. It feels like we’re the chosen ones. I’m just in the right place at the right time. Not to sound cliché, but people can either wait for things to happen, or take the road less traveled and find other people traveling that road who don’t have the platforms to be heard. Like what Bey did on Cowboy Carter, grabbing different artists like Shaboozey. Look at him now. Look at Ryan grabbing Miles and giving him a platform.

There’s a lot of people who don’t have a platform and probably could do it better than we’re doing it. But with these projects, we’re showing that we hear you. We hear that something real has to happen in music and film. We’re the ones chosen to raise the bar – and the bar has been pretty low in a lot of different areas. Some choose to not let the bar be that low, and that’s what happened. When somebody calls your name, you go to be ready.

Your one man show, No Bandwidth, kicks off at the end of May. What are you most looking forward to about taking the stage by yourself?

Looking at Neil Young’s one-man show and watching Mike Tyson’s [show] is what really made me want to do one. When I saw it years ago on HBO, I was like, “Man, Mike did a good job. I wanna do that!”

I feel like I have some stories to share with people about my life, and [I get to play] some of my favorite songs. I’m gonna play a little bit of piano. I’m no Prince on the piano, but in the pandemic, I fell in love with the piano. I might play a couple of tunes I learned during that time. When I was a kid, I took piano, but I quit because I wanted to go play basketball and football with my friends. My teacher told me, “You’re gonna wish you kept playing,” and I knew she was telling the truth, but I was already pretty good on the bass. [Laughs]. But I’ve always written songs on piano, just never retained anything. Now, I’ve bought maybe three or four different pianos, so I took up lessons again.

Why did now feel like the right time to open up the vault and launch your vinyl club?

Some people may have loved some of the music that I put out, and some of their friends may have never heard it. It’s always good to be discovered. If you can be discovered twice, and be discovered on vinyl, that’s even more of a thrill for me. It also puts you in a different creative space of creating artwork, which makes them more of a collector’s item. It kind of feels like when the Grateful Dead had people going to different cities just to get different cassettes with different artwork.

I [also] wanted to create some new vinyl with music I haven’t even made yet. I wanted to start [the vinyl club] off with some things I have in the vault.

Where do you hear the blues today?

I once talked to B.B. King, and I asked him, “You think more Black people should play the blues?” He said, “Let them do what they do, and we do what we do.” I think the energy came from his being okay with his huge fan base playing the blues. But I felt like more people should know about it and play it. It’s a big genre. It’s something you should always have in the vault and listen to.

I think where it is now in the South is more like [Hampton, Va.-born soul/R&B singer] King George’s “Keep on Rollin.” That’s the blues today. Sometimes when you hear different MCs, they also sound a bit bluesy to me. But in terms of blues guitarists, it’s more others doing it than us. That’s just how it goes. But back in the day, that Delta blues was just a whole different life, a second language.

Indie rock shows are often the province of, as LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy said in the band’s “Tonite,” “the hobbled veteran of the disc shop inquisition” — the graying, largely male species of armchair critics who listen to Sirius XMU and love to lord their music discoveries over those less informed. Not so with Car Seat Headrest: The Seattle-based band’s concerts attract a fascinating cross-section of fans. Yes, the geezers are there, but so are the moshers, frat bros, furries, and — lending hope to the future of rock’n’roll — millennials, Gen Z and even a smattering of Gen Alpha teens letting their freak flags fly.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Car Seat Headrest’s music speaks to this multitude of generations in part because, musically, they have synthesized their many individual influences — past and present — into a sui generis sound. The band’s leader and primary lyric-writer, Will Toledo, grew up listening to his parents’ folk and country albums, as well as classic rock, r&b and soul. CSH’s guitar genius Ethan Ives lately has been listening to Beethoven, Pentagram and King Crimson. As a unit, the quartet, rounded out by drummer Andrew Katz and bassist Seth Dalby,’ have played and toured together for the last 10 years or so — circa the release of 2016’s breakthrough album, Teens of Denial, and in this time they have achieved a virtuosity that stands out among their peers.

Trending on Billboard

Lyrically, Toledo has largely avoided pop and rock tropes, like romantic love, sex and heartbreak (although drugs often figure into his songs). He prefers to gouge deeper into tough, unsolvable existential topics: alienation, familial relationships and the melancholia that comes with growing up in the digital miasma of the 21st century.

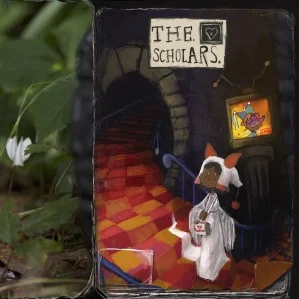

These outsized talents and a sizable amount of ambition — long a CSH trait — all come together impressively on the band’s first fully collaborative album, The Scholars, a rock opera that is destined to stand with landmark recordings from previous decades: The Who‘s Quadrophenia (1973), Pink Floyd‘s The Wall (1979); Drive-By Truckers‘ Southern Rock Opera (2001) and Green Day‘s American Idiot (2004).

The Scholars, which Matador will release on May 2, stands apart from those other epic recordings in that it is more of an existential exploration than a strictly conceptual one. It’s a musically rich story propelled by a succession of characters — some who interact and some who don’t. (Ives compares it to Paul Thomas Anderson’s 1999 film, Magnolia.) The album is set in and around the fictional Parnassus University, populated by numerous characters — Beolco, Devereaux, Artemis and Rosa, among them — and narrated by The Chanticleer, a Greek symbol of courage and grandeur, and in Old French translates to “to sing clearly.” The antique-sounding names and places seem to be a conceit to show that past is prologue. Even when songs allude to cancel culture (“Equals”) and societal and environmental decay (“Planet Desperation”), these are not new problems. They’re just disseminated now by social media, not a Greek chorus. It’s the kind of album that will resonate with young folks forced to move back in with their parents because of the economy and the parents who are housing them.

The Scholars requires a certain amount of commitment. Three of the songs, “Gethsemane,” “Reality” and “Planet Desperation” break the 10-minute mark, with the last of the three clocking in at 18:53. And yet, the lion’s share of the songs come with sticky hooks that build and progress in a way that belies their length. “Gethsemane,” which approaches 11 minutes in length, is even getting a good amount of play on Sirius XMU, and the album’s pinnacle, “Reality,” in which Ives and Toledo share vocals — they liken it to Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb” — could easily go on beyond its 11:14 run time.

Dalby, Ives, Katz and Toledo came together on Zoom to discuss the making of The Scholars, the ideas behind the music and lyrics, their upcoming tour and their side projects. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Sonically, The Scholars reminds me a bit of David Bowie’s Blackstar in that there’s such a symbiotic feeling to the music. You feel that you’re inside it. How did you guys achieve that?

Will Toledo: I don’t recall everything about the Blackstar sessions, but I feel like they probably worked and jammed together. I think the musicians he recruited were already kind of a unit, and they were used to improvising together and collaborating. You have that symbiosis, because that freeform mesh was already there.

For us, some of the material came out of solo demos from me and Ethan and everybody else, but a lot of it resulted from us just jamming in the studio together. We’ve had ten years of being a band, and mostly our opportunities for jamming were limited to soundcheck when we were not ready to soundcheck or practices when we were not ready to practice. This was the first opportunity where we would go in and spend a whole practice session just jamming. We really wanted to get loose with one another, fall into comfortable patterns and just go wherever the music was taking us. That resulted in an interchange — a more distinct weaving together of our voices. Whereas past records were more about solo material brought in to be played by the band.

Ethan Ives: We have a lot of musical influences in common, but we also each listen to our own individual styles of music. On this album, what you’re hearing is that we had a directive for each song. It was okay, this song needs to go to this place or touch on this theme. Part of the process this time was about throwing that to the room and then playing the flavors of music that we’re [each] familiar with to build out the song. So, maybe there was more of a deeper well of stuff getting pulled on in this one.

Toledo: What I see in myself and how I play into the band — I’m very sensitive to sensory experiences and social experiences and I do tend to automatically hone in on, here’s the part I like. That kind of comes naturally to me. I’m always picking up stuff as I go, and thinking, “This doesn’t make me so comfortable.” Or, “Ooh, I want to change that more.” What I’ve had to work on more is patience and not judging stuff right away. Because especially in a jam you want to let stuff build organically. Really, for this record I was just trying to come in and listen to how the other three were intersecting, and just as far as what I was playing, push that and weave that together. I feel like my strength is more as an arranger than as a sort of composer from nothing.

Will, are the lyric credits all yours?

Toledo: Most of them. Pretty much anything that Ethan sings lead on he wrote, and for songwriting credits we just do a four-man split — that was what we agreed on going in, because of the way that we were creating this music. For most of the songs, I would take them home and write lyrics, especially for pieces that Ethan had come to the band with. He was developing the lyrics there as well.

Before Making a Door Less Open, a lot of your songs sounded like they could be pieces of a rock opera. Is this something you’ve had in mind for a long time?

Toledo: Growing up with records like Dark Side of the Moon and Pink Floyd in general and The Who, I was always aware of the possibility of a concept album or a rock opera. I always shied away from the idea of doing it because it’s a pretty daunting concept and I didn’t want to sacrifice the song-by-song quality of things to make some sort of narrative. After Making a Door Less Open, though, that was an approach where each song was really its own world, and the record came out a little disjointed because of that. You have to magnify with a microscope each one of those songs to appreciate it. That’s an interesting approach, but I wanted a more cohesive flow to an album.

So, I felt more inclined to go in the opposite direction. I landed on a midway approach, where we weren’t going to force a narrative, but have this idea where each song is a character. That way, we can still preserve the integrity of each song and feel good about the ones we put on the album. But then there’s that inherent narrative quality that comes when you’re seeing each character come out on stage.

Car Seat Headrest

Courtesy Photo

How would you synopsize The Scholars?

Ives: Part of what I feel a sense of accomplishment about and what I feel is successful about the album is that it’s my favorite type of conceptual record as a listener. Which is that the narrative is not so rigid that it has an authorial narrative interpretation. Pink Floyd’s The Wall has a very specific meaning. That’s not a weakness, but it is a very particular style of concept. I tend more towards albums that have conceptual threads but are more interpretable or more based on abstractions. We probably all will have a different version of what we think the album represents, but I think of it as tracking the lives of a bunch of different characters to amalgamate a greater life/death/rebirth cycle. It’s a cycle that could be seen as one person’s life, but it’s really a series of different story beats made from moments in different people’s lives, in a Magnolia sort of way.

Toledo: My interpretation wouldn’t be too different. Like Ethan, I prefer concept albums that aren’t so rigid that it has to be this plot. I was hoping for a record where you could put it on and not know that it was a concept album, or that there were these characters or this backstory, and still have a full experience. We wanted the music to speak for itself. As far as selling it to someone who needs a description, I would say it’s about weaving together the past and the present and having these young characters — who maybe don’t know a lot about the past and have problems that are more specific to our times — walking through these patterns that are quite ancient or timeless. I was pulling a lot from folk song tradition in crafting these characters and their struggles. In folk songs, you can see what people have been talking about for centuries and centuries and what really has sticking power.

Seth Dalby: I think Ethan and Will definitely have a more concrete idea of where each character lives and what their struggles are. For me it’s just a place to get lost. The setting is obviously like a fantasy school, and then your imagination goes wild with these characters.

Andrew Katz: You’re scraping the bottom of the barrel now for these answers. I’m not a guy that listens to lyrics. I listen to syllables and music. Asking me what an album means — you’re asking the wrong guy.

Toledo (to Katz): What would you say to yourself, if you had never heard this record, to say you should listen to it?

Katz: I would say it sounds epic. I go off of feel and how the words roll off the tongue. Even when I’m listening to songs by System of the Down, for example. They do a great job of just making s–t sound cool. I have no idea what any of those songs mean — what they’re supposed to be about. They just sound cool. I would say our album achieved that, too. It’s epic.

Will, you told Rolling Stone that The Scholars was an “exercise in empathy.” When I listen to the album, I hear a search for identity that comes with extreme sadness and pain. Does that sound right?

Toledo: Yeah, absolutely. One of the early concepts that I was working off is — it’s all these different characters, but it is also on a more spiritual level, one character and their progression through life, and even life and death. But maybe the life and death of an identity. I see this shaking off of the old and reaching towards the new, and there’s a lot of darkness and pain that comes along with that. You have to walk into the darkness to find out more about who you are. I kind of see each song as a step along that way.

Will, when the band performed the album at the Bitter End in February, you dedicated the song “Reality” to Brian Wilson. You called him “a prophet who lives in the darkness.” Ethan, you read a note about what you described as a generational divide. It sounded like you were talking about the Boomers and Gen X, but you all are millennials. Could you both elaborate?

Ives: Those things got all jumbled up for me in my upbringing because my parents were so deeply hippie that I feel like I skip a generation. I don’t want to give the impression that the whole song is purely about complaining about Boomers, but it’s a song that I picture as the main thrust of the character who wakes up one day and is like, “How did I get here? Why am I here? Why is this happening to me?” And then tries to trace back the chain of events that led things to turn out this way. And maybe there’s some regret and some reproach for other people or for an earlier version of yourself.

Will and I each wrote our respective lyric segments in that song, and I always thought of it as a “Comfortably Numb” vibe, where one singer takes one narrative point of view, and one takes another. We’re coming at the song from two different angles and meet in the middle where the emotional core of the character that I just described fits really well with the figures that Will was referencing in the lyrics. Artists like Syd Barrett or Brian Wilson, who experienced so much brilliance in their lives and then probably at some point just woke up late one morning and were like, “What happened to me?”

Toledo: Like Ethan said, we wrote our own parts coming at it from different perspectives. With the line, “We still sang songs and made merry, but deep down we knew something was wrong,” I got the sense that my voice would be as the Chanticleer character. So, when Ethan is singing, you have the voice of those people expressing this dissatisfaction and the feeling of, where did we go wrong. The Chanticleer character became for me this artist figure who has chosen to elevate the struggles of the people and, as artists sometimes do, chase the spotlight. The burden that comes with that is you have to dig into the hearts of people and find a deeper truth. I have these two choruses where they’re coming to the Chanticleer and saying it’s not enough. We need more color. We need more life. Then in the second chorus it’s too much. We can’t take it anymore.

The role of the artist —especially that Syd Barrett/Brian Wilson type — is a bit of a toxic one, because culture really elevates those who fly very close to the sun and get burnt. It lets them suffer for the sake of being that preacher. I have a conflicted relationship with it, because I loved these artists and the idea of that kind of artist when I was a kid. And I played my part in elevating that idea of artistry. Now I try to find other models that are more stable. But there is a basic truth where, if you want to dig and try to speak those deeper truths, you do get burned.

Your parents were in the audience at The Bitter End. A lot of Car Seat’s music — I’m thinking of “There Must Be More Than Blood” and on this album, “Lady Gay Approximately” — have parental or familial themes.

Toledo: Yeah, on this record specifically, but even beyond that when it comes to writing about love, I’m just not that interested in writing about romantic love and partner love. That is really almost the only type of love that you hear when you think about a pop song. I look towards other traditions, and especially in country and gospel tradition, there’s a lot more of singing about parent-child relationships. That seemed like a more meaningful thing to me to write about.

“Lady Gay Approximately” is based on a folk song called Lady Gay which is about a mother and her children. I was also looking towards the bible for inspiration and in Genesis, a lot of content is about parents and children; fathers and sons; mothers and sons. This model of love is the one that we know throughout all our lives. So, it seems like it’s more relevant and important to write about. And that became a focal point of this record.

Do you guys have any thoughts of staging this as a rock opera? I don’t know if any of you saw Illinoise, the dance musical built around Sufjan Stevens’ music. Also, I could see this being made into a movie like the animated film Flow. Given the love that the furry culture has for you, I could see the director of that film [Gints Zilbalodis] doing something fantastic with the album.

Katz: Hey, if the director of Flow wants to make a movie about our album, yeah, for sure. That would be great.

Toledo: I’m usually the brake presser as far as opportunities, because there are plenty of things that we can do, and it’s more of a question of, “What do we want to take on this year? How many things can we take on before things start splitting off?”

Right now, we’re happy and we’re busy. We’re practicing for our show, and we are going to be playing this record live, but it’s just going to be the band and some lights. There’s not going to be any elaborate staging beyond that. We figure the music speaks for itself. We would rather have something simple where we can really feel like we’re comfortable onstage. With [Making A Door Less Open], we upped the theatrics, we upped the costumery, and it was kind of a drag. There was a lot to worry about every night — a lot that can go wrong. We all prefer to keep it as simple as possible on our end and give it a better chance of being good and replicable every night.

Beyond that, we’ve got a Patreon. Every month, we’re putting out content there. I’m trying to write two new songs every month and put them out. As far as more content for Scholars, more adaptations of it, as Andrew said the right offer might come along and then we’d consider it. But as far as actively pursuing it, we’re happy with the workload we’ve got at the moment. I would say, “Let people sit with the album, come up with their own images of it — and if something else comes out of it, let it be organic.”

Are you going to play the whole album on the tour?

Toledo: It will be more or less the whole album. We might skip a song or two, but the idea is to keep that flow. Practicing for the Bitter End and earlier, we all just agreed that this album has a good flow from start to finish. It feels good as an album and it feels good as a show.

When I go to your shows, I just see so many different types and ages of people. Why do you think you appeal to such a wide array of music lovers?

Toledo: That’s one thing that’s always really pleased me about our live shows. There’s always a big mix. I think it started out with the way that I approach music. I didn’t grow up enjoying modern pop music. I trended heavily towards what my parents were listening to — so ‘60s music, older country and folk music. That gave me a backbone musically that differentiated the early Car Seat Headrest music from what other people were doing. It was a little more isolated, and I think, because of that, it took several years before it started to find an audience. Younger people connected with the emotional content, which was as a young person writing lyrics and content. I was expressing stuff that they could relate to as well.

And then, as we became a band, rather than homogenize and do something that appealed to one audience, we were all bringing different stuff to the table. We’ve always just had that approach of: cast a wide net, see what the overlap is, see what we can all agree on. And then that diversity of opinion and approach creates music that resonated with a lot of different people.

Most you have released side projects. Ethan, is there a new Toy Bastard album in the works?

Ives: There’s one that came out last summer, The War, that I’m still repping to people. I worked really hard on it and was very pleased with it. I worked with Jack Endino [Pacific Northwest producer of Nirvana, Soundgarden, L7] a little bit. He engineered a portion of the tracks, and he was fantastic. You can tell the songs that he engineered because they have a special flavor that only he can bring.

Katz: I’m working on a new 1 Trait Danger album. Who knows when it will be out? I’ve got nine songs done, but I’ve got to meet with Will when he’s ready and get him to orchestrate the story. Will’s job is to create the narrative with the crazy songs that I make.

Dalby: I don’t know if mine is ever going to be out, but it will be finished at some point.

Ives: I feel like you’ll finish it and then just put it on a hard drive and lock it away.

Katz: No one is ever hearing that music.

What are you guys listening, reading or watching right now that moves you?

Ives: I’ve been listening to a lot more classical music. A lot of the late Beethoven string quartets but then mixing them up with listening to a lot of Pentagram and King Crimson.

Toledo: I’ve been a little scarce on consuming music. I just realized that my life was kind of surrounded by movies and TV and music. Lately I’ve been trying to just cut back and enjoy silence and whatever sounds are in the sphere that I’m in. And just talking to people really. I mainly listen to our own music because we go in and practice it. Or writing and practicing the new material and putting it out on Patreon.

Do you guys ever talk in terms of a five-year plan?

Katz: No, but I like where your head is at. I see myself in a huge mansion on the water. It’s a pipe dream, but that’s where I see myself.

Ives: I feel like we have our version of that, and then the way that music and the music industry works, we always end up having a completely different thought about it 12 months later.

Toledo: For us, five years is baically an album cycle — so where we’re at in the cycle is where we’re at in the five-year plan. We don’t discuss it that often, because it is what it is. Right now, we’re basically on the final year of the Scholars cycle — maybe another two years — but it’s more about seeing where we’re at and what work we’ve got to get done.

On her new album, Cosas Que Sorprenden A La Audiencia (Things That Surprise the Audience), Vivir Quintana uses the strength of her voice and the power of her words to tell real-life stories of women who were imprisoned after killing their abusers in self-defense. She does so through the corrido, a traditional Mexican genre often associated with glorifying violence and misogyny — but transforming it into a narrative of denunciation, dignity, and justice.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Told in the first person, Quintana’s sophomore LP is the result of a decade of research and collaboration with women who shared “their hearts, their homes, and their cells” to recount their stories and the reasons that led them to defend themselves against their abusers, ultimately losing their physical freedom after being accused of “excessive self-defense.”

Trending on Billboard

“Fifteen years ago, a friend of mine was a victim of femicide, and it made me incredibly sad — I didn’t know who to blame or how to cope,” the Mexican singer-songwriter shares in an interview with Billboard Español. “For a long time, I kept thinking about what would have happened if my friend had killed her abuser instead of him killing her.”

Her friend’s femicide inspired her popular 2020 release “Canción Sin Miedo” (Song Without Fear), the powerful feminist anthem that accompanies marches and protests against gender violence in Mexico, as well as the fight of mothers searching for their missing children.

But in her album Cosas Que Sorprenden A La Audiencia, released last Thursday (April 24) on digital platforms, the artist, originally from the northern state of Coahuila, goes further by reflecting deeply on the causes of machista violence — the same that results in the killing of 10 women every day in Mexico for gender-based reasons, according to reports from UN Women.

Released under Universal Music, the album features 10 corridos, a genre that emerged during the Mexican Revolution (191–1917) as an alternative account to official history, according to experts consulted by Billboard Español.

With resonant guitar sounds and a powerful accordion, Quintana uses this musical style — characteristic of the region where she was born and raised — to tell stories like that of Yakiri Rubio, the protagonist of the song “La Nochebuena Más Triste” (The Saddest Christmas Eve). In 2013, Rubio was kidnapped by two men who took her to a hotel to sexually assault her, and she ended up killing one of her attackers in self-defense.

Another example is the corrido that opens the album, “Era Él o Era Yo” (It Was Him or Me), which narrates the story of Roxana Ruiz, who was sentenced to six years in prison for killing her attacker in 2021. “Files and more files/ With my name and the names of other women/ Who fiercely dodged death/ Justice destroyed our luck,” goes part of the lyrics.

The album also includes titles like “Mis Cuarenta” (My Forty), “Mi Casita” (My Little House), “Más Libre que en Casa” (Freer Than at Home), “Mi Cobija” (My Blanket), “Claro Que No” (Of Course Not), “Kilómetro seis” (Kilometer Six), “Al Tiro” (At the Ready), and “Cosas Que Sorprenden a la Audiencia,” the album’s title track, inspired by Marisol Villafaña, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for defending herself against her abusive husband.

“That’s why the album is named this way,” Quintana explains, “because we’re so surprised when a woman defends herself, but we’re not surprised when a man receives an exemplary sentence for committing femicide.”

Recognized in 2024 as one of the Leading Ladies of Entertainment at the Latin Grammys, the 40-year-old artist is one of the new faces of corrido music in Mexico, although she has revolutionized the genre since her debut over a decade ago, by using music as a tool for activism and denunciation. In addition to “Canción Sin Miedo,” she is the author of “El Corrido de Milo Vela” (The Milo Vela Corrido), a tribute to journalist Miguel Ángel López, who was murdered in 2011 along with his wife and son in Veracruz. In 2024, she also wrote “Compañera Presidenta” (Madam President), a letter dedicated to the then-possible first female president of Mexico, a position now held by leftist Claudia Sheinbaum.

“With this album, I hope people open their hearts — but beyond that, I hope they open their minds to understand that gender violence needs to be addressed by all of us,” Quintana says. “And may we never forget that the voices of women deprived of their physical freedom also matter.”

Regarding the controversy surrounding corridos that glorify drug trafficking — subject to bans and restrictions in public spaces across ten Mexican states, though not officially prohibited by the federal government — Quintana believes that prohibition “is not the solution.”

“The children born into a world of organized crime, where their social context is that, where their family members are part of that life, and one day they realize they want to sing or play the guitar — what are they going to talk about?” Quintana questions. “Music is nothing more than a reflection of the reality or social context you live in, so narcocorridos should be regulated, but through education. That way, we can distinguish between reality and fiction, between good and bad.”

Turning 40 led Natalia Lafourcade to discover CANCIONERA, the vein of the message that fuels her new musical project, the character that brings her alter ego to life, and the concept of a tour that will take her around the world for more than a year to perform her artistic creation live. A year later, with the release of her new album on Thursday (April 24), the acclaimed Mexican singer-songwriter says that this work reaffirmed her role in life and the path she wanted to follow.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

“I feel that CANCIONERA came to remind me of that message as a songstress, but it also made me feel very inspired by songs from around the world, at a moment in my life when I said to yourself, ‘I’m 40 now, what’s next?’” Lafourcade tells Billboard Español in an interview in Mexico City.

Trending on Billboard

The LP follows De Todas Las Flores, her celebrated 2022 album that earned her a Grammy Award and three Latin Grammys and marked a creative partnership with her friend and colleague, Franco-Mexican producer, musician, actor, and director Adán Jodorowsky. Again, they collaborate on CANCIONERA, which was entirely recorded on analog tape in Mexico.

The album also features contributions from El David Aguilar, Hermanos Gutiérrez, Israel Fernández, Diego del Morao and Gordon Hamilton, who enrich the set with nuances and textures ranging from bolero to son jarocho, with hints of tropical and ranchera music. Additionally, the work of Soundwalk Collective adds a sound design that complements the album’s depth, integrating natural sounds as part of the musical landscape.

The repertoire of CANCIONERA, Lafourcade’s 12th album, includes original compositions and a couple of reinterpretations of traditional Mexican music, such as the son jarocho songs “El Coconito” and “La Bruja,” which establish a dialogue with the essence of the project. Released by Sony Music, the album consists of 14 tracks, including an acoustic version of “Cancionera,” where she explores sounds like bolero, son jarocho, tropical music, and ranchera, very much in the style of the iconic Chavela Vargas. Other titles on this production are “Amor Clandestino,” “Mascaritas de Cristal,” “El Palomo y La Negra,” “Luna Creciente,” “Lágrimas Cancioneras” and “Cariñito de Acapulco.”

The four-time Grammy and 18-time Latin Grammy winner — recently highlighted among Billboard’s Best 50 Female Latin Pop Artists of All Time — admits that her alter ego in this new project pushed her to do things she, as Natalia Lafourcade, wouldn’t have done. “This songstress soul cornered me into maximum creativity through dance, exploration of movement, exploration of painting, many things I love and had perhaps kept locked away in a drawer,” she says. “It shows that this is a new facet, a stage that taught me about the capacity I have to transform, and not just me, but everyone.”

And unintentionally, she confesses, Mexico — through its traditional rhythms, lyrics, and songbooks — once again permeated her work, just as it did in her previous albums Un Canto por México (2020), Un Canto por México II (2021), and De Todas las Flores (2022).

“I think the album has a lot of Veracruz in it, a lot of our way of speaking, our wit. And again, without seeking it, without forcing it, all the influences of those involved and that sense of Mexican identity came through,” Lafourcade explains. “Just as Emiliano Dorantes brought the influence of Agustín Lara, ranchera Mexico came through, tropical Mexico with Toña La Negra, the Mexico embodied by Chavela Vargas. All those glimpses manifested in the process. I loved that because it shows that we’re all here and we exude that Mexican spirit.”

Additionally, she points out, the new songs conveyed fantasy and a surreal touch, “what happens as if in a dream.” Without hesitation, she knew her new album needed to feature Jodorowsky as co-producer, whose critical and sensitive ear would help her direct her creations.

“Creating with Adán is one of the most beautiful things. Besides Adán, there was David Aguilar, Emiliano Dorantes, Alfredo Pino, my lifelong musicians, people I love and admire, all gathered in a studio, playing, making music — some of the happiest moments of my life creating,” she says. “And Adán, I really appreciate his philosophy of life, his way of working, his friendship, the way he loves me. I’ve found in him a producer who understands both my roles: as a producer and as an artist.”

The singer of “Hasta la Raíz” notes that with Jodorowsky — son of the renowned Chilean-born filmmaker, theater director, psychomagician, writer, and producer Alejandro Jodorowsky — she knows she can fulfill her role as a producer and songwriter without losing focus. “When you go into the recording studio, you’re so vulnerable; everything happens — there’s joy, and there’s also confrontation. There are days when you’re having a terrible time, when you’re very fragile and need a sensitive person. That’s Adán.”

Lafourcade shared that before CANCIONERA became a conceptual album, it was initially envisioned as a tour with just her voice and guitar on stage. “That was the first spark that led us to create an entire album.” Thus, a series of intimate concerts in Mexico, produced by Ocesa to promote the album, began on Wednesday (April 23) in Xalapa, Veracruz, and will arrive at the Teatro Metropólitan in Mexico City on May 2, before returning in September to the Auditorio Nacional. With stops in several cities across the country, the United States and Latin America, the CANCIONERA Tour is shaping up to be one of Lafourcade’s most ambitious ones.

With Mexico as one of her greatest inspirations, and after having elevated the country’s name with her music, Lafourcade applauded the government initiative México Canta, announced on April 7 by president Claudia Sheinbaum to promote songs free of violence glorification. “I agree that it’s time to analyze a little and open our eyes, to be aware that music has a lot of power,” Lafourcade says. “Sung words have an even greater power; they truly affect us, transform us, for better or worse. It’s a transformation on a level we don’t even realize. I think a constructive perspective is always a great contribution.”

Some artists break through with their very first single; others go their entire careers unheard. Trinidad Killa, who’s been in the music industry for a quarter-century now, got his long-overdue break nine years ago, but a recent career-shifting collaboration with Billboard’s No. 1 Greatest Female Rapper of All Time sent an entirely new – and infinitely stronger – wave of momentum his way.

Hailing from Arima in Trinidad & Tobago and currently residing in Flatbush, Brooklyn, Killa has always followed wherever his creative inclinations led him. In the early-mid ‘10s, Killa frequently entered music competitions – from Soca Star and Digicel Rising Stars to more local street showdowns. In those clashes, Killa’s near-perfect victory streak earned him his nickname, and he continued honing those skills on Basilon Street, the area of the island that would give way to a popular subgenre of Trinbagonian dancehall called “zess.”

As one of the self-proclaimed pioneers of zess, Killa scored one of the style’s earliest hits with 2019’s “Gun Man in Yuh Hole,” which he’s since parlayed into his first three nominations at the Caribbean Music Awards. As exclusively revealed by Billboard, Killa earned nods for zess-steam artist of the year, best new soca artist and the soca impact award.

Trending on Billboard

Much of Killa’s recent motion has come off the back of “Eskimo,” a song that nearly disappeared into the ether after it was initially recorded in late 2024 over an unauthorized use of Full Blown’s “Big Links” riddim, which has spun out massive hits for Yung Bredda (“The Greatest Bend Over”), Machel Montano (“The Truth”) and Full Blown themselves (“Good Spirits”) this carnival season. Once Killa smartly (and quickly) cut “Eskimo” over a different riddim, he successfully shot his shot and secured Trinidadian-American rap icon Nicki Minaj for the remix, which lifted to song to No. 2 on World Digital Song Sales this spring (chart dated March 15).

“I always try to show people that music is a mission, not a competition,” Killa tells Billboard. “In order for soca music to reach where it’s supposed to reach, everybody must get a fair chance and a fair opportunity – and that’s what Nicki gave me.”

In a sprawling conversation with Billboard, Trinidad Killa breaks down how Nicki Minaj got on the “Eskimo” remix, his rocky relationship with the Trinbagonian music industry and the true origins of zess.

What are some of your earliest musical memories?

Trinidad Killa: I grew up going to church every Saturday with my mom and my brothers and sisters, just listening to the music and vibing. I’ve always loved music – from winning school competitions to chanting on the streets. I remember when I was in Soca Star back home in Trinidad and Tobago, and I came in seventh place. That was my first competition, and Digicel Rising Stars came after.

Where were you when you found out about your Caribbean Music Awards nominations?

I was at home, and somebody sent me a message on Instagram saying that they voted for me. I does be so busy that I ain’t really paying attention to social media. When I saw that in my inbox, I went to the [website] and saw I was really nominated in three categories. I’m one of the people who created zess music, so I feel very good within myself knowing that something I helped create is being recognized by the Caribbean Music Awards today.

What do you love most about zess?

People back home in Trinidad & Tobago give zess a bad [name], but zess is about enjoying yourself. I want to get that clear, because [some] people feel zess is about men doing the wrong things. The word “zess” comes from a spot where we used to party back in Trinidad & Tobago named Basilon Street. People would come on Friday and catch themselves still there on Tuesday and Wednesday with the party still going on. Everybody would say, “We goin’ down in the zess” because when you pulled up, that’s where the party was happening. Down in the zess, you have plenty men with big chains, men smoking weed and drinking and just having a good time. Zess is a form of enjoyment.

How do you assess the 2025 soca scene?

Back home, I is a real ground man. I built myself up from the ground, and there’s plenty [people trying to] fight me down in the music industry because I is a real talented person. In the music industry in Trinidad and Tobago, it’s about who knows who. So, I decided to leave and come to America and ended up doing a soca song this year on Full Blown’s “Big Links” riddim. When I first heard the riddim, I thought it was real bad and I wanted to be on it; I reached out to the producers and let them know that.

I am so feared in the music industry in Trinidad and Tobago that they don’t want my music to go through the right channels, so they was denying me the rights to [record] on the riddim. That riddim used samples from my song, “Gun Man in Yuh Hole,” so I feel like I had a part to play in that whole thing. It’s only right that if you use something to create something new, you should bring those [original] creators along. They used [our] thing to make something else and then put other artists on it.

How did Nicki Minaj end up on “Eskimo?”

I decided to jump on the riddim and pen a song, because I was in New York and couldn’t go back home for Carnival. I was going through so much in my career — they weren’t playing my music on the radio, and I was just fed up. I didn’t come to America with a visa, so being here and knowing I couldn’t go back home was very depressing. My producer and I [channeled those feelings] into a new tune, and that’s how we came up with “Eskimo.”

When we put out “Eskimo,” it was getting so much traction that they ended up pulling down the track [due to its unauthorized use of the “Big Links” riddim] – even after it hit 100,000 views in [two days]. That was very heartbreaking. I sat and prayed on it and decided to build a different riddim and put “Eskimo” over it. The day we were going to put out the new version [on the “Bigger Links” riddim], Nicki Minaj hit me up and said, “Nice track, [this is] wonderful.” So, I went into her inbox and asked her to be a part of the track, and we ended up putting it out together. That was one of the biggest achievements in my entire career.

What was your reaction when you saw “Eskimo” hit No. 2 on Billboard’s World Digital Song Sales chart?

I was speechless. Everything I put my mind to as a yute, I achieved it – from entertaining to owning a restaurant to coming to America. I had to pinch myself because I felt like I was still dreaming.

What exactly did Machel Montana mean when he asked you and Nicki to “stop fighting him down?”

Me and all entertainers in Trinidad are good. I was young, mashing up the stage with Machel and them at the age of 16-17 – and these fellows never really gave me an opportunity or a stage-front. Really and truly, Machel and them just want everything in the music industry. They want to be the face of soca, and that is why I fight for other artists and for the common yutes to get an opportunity.

I was the first man to even put Yung Bredda in the studio, and gave him his first hit song. Lady Lava, all of them, I have history behind me. When I get blessed, I always like to bless somebody else — that’s how I will continue reaching different heights. When Machel saw I did a song with Nicki Minaj, he felt a type of way, knowing that he is the King of Soca and he never took an opportunity to give me that platform, [despite] knowing that I’m a good artist. And Nicki came and did it! While on stage, in the hype of the moment, he said something he wanted to say all this time — but he thought nobody would pick up on it.

Have you met Nicki yet? Has she given you any advice as you navigated this next stage of your career?

I haven’t met her yet, but soon. She always tells me to stay focused and gives me positive [affirmations] for my daily life and career. Everybody looks up to Nicki; to have a collaboration with the queen of rap music is a huge accomplishment [for] me.

When did you decide to start going by Trinidad Killa and why?

They used to call me “Killa” because I was involved in plenty song clash. 99% of the time, I won those competitions, so [I got the name]. When I got my first hit in the industry, I tried to change my name 20 times, but “Killa” stuck. I [decided] to put “Trinidad” in front of the “Killa” because that’s what people know me as, especially because there’s already Bounty Killer, Mr. Killa, etc. I also put the “Trinidad” in front so when people hear “Killa,” they don’t feel like it’s anything negative.

“Gun Man in Yuh Hole” or “Good Hole?”

I was in the venue freestyling “Gun Man in Yuh Hole,” and somebody uploaded it online and it went viral on social media. Someone took the vocals from that clip and put it on a riddim, and that’s how I got my break in the industry. I never went to a studio to record “Gun Man in Yuh Hole,” so it will always be one of my favorite tunes. That’s a foundational tune. It brought me to BBC 1Xtra and around the whole Caribbean.

When can we expect your next album?

I hope I finish in time, but I want to put out the album the same night as my next show on May 24. I’m not just a soca artist, I have reggae, dancehall and Afrobeats tracks. But I love soca, that’s my culture, and that’s where I come from.

Where is the oddest place you’ve heard one of your songs?

Dubai. Someone tagged me in a post, and in a club in Dubai – a real rich party – people were dancing to “Gun Man in Yuh Hole.”

Who’s the greatest rapper of all time?

Nicki Minaj.

What’s your favorite meal?

I’m a cook as well, so I cook for myself. I had a restaurant, but I had to ease off and focus on the music when I came to America. I used to sell [food] on [Eastern] Parkway, and we would have people lining up by the hundreds. In Trinidad, I had a big restaurant, and I cooked anything – you name it, and I make it.

What do you hope to achieve by the end of 2025?

Getting my own restaurant in New York City.

At the age of 10, Melody became a precocious phenomenon in Spanish pop with “El Baile del Gorila,” the lead single from her album De Pata Negra, which led her to embark on an international tour. Twenty-four years later, the singer and songwriter is facing the challenge of representing Spain at the 2025 Eurovision Song Contest, which will be held on May 17 in Basel, Switzerland.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

The song she will perform is “Esa Diva,” a pop track that’s both a vocal challenge and a manifesto of empowerment. “A diva is brave, powerful/ Her life is a garden full of thorns and roses/ She rises up dancing/ Stronger than a hurricane,” goes part of the chorus, in Spanish. With an intense performance and dynamic staging, Melody is aiming for more than just a show — a story with purpose and soul.

“I didn’t want to go with an empty dance song. I wanted it to have a message, strength, to speak about something that happens to all of us,” the artist explains in an interview with Billboard Español.

Trending on Billboard

The song has been widely embraced since its debut at the Benidorm Fest, evolving with new versions. The original was co-written by Melody and Alberto Fuentes Lorite and produced by Joy Deb, Peter Boström, and Thomas G:son. On March 13, a symphonic version was released, arranged by Borja Arias and performed by Melody alongside the RTVE Orchestra and Choir, adding a more cinematic and emotional dimension to the track.

“I wanted to show it in a different way. I’m a fan of soundtracks, and this song called for an orchestral treatment,” Melody says. “If a rhythmic song works as a ballad, it’s a great song.”

Beyond the music, “Esa Diva” has become a symbol. “The diva isn’t just the one who shines on stage –she’s the one who fights, the one who falls and gets back up. The one who supports other women. The one who is strong, but also humble,” Melody notes. And many people have found comfort and inspiration in this message. One of the anecdotes that has moved her most is about a young woman undergoing cancer treatment who listens to the song daily to gather strength.

Although this is not the first time Melody has tried to represent Spain at Eurovision — she did so in 2009 with “Amante de la Luna” — she feels that now is the right time. “If I didn’t do it now, I was never going to do it. It was the moment,” she adds. “I feel it, and I’m enjoying it like never before.”

Her victory at Benidorm Fest 2025 confirms this: She was the audience favorite, earning first place in the tele-vote with a solid 39%. Although the jury placed her third, the combination of both votes secured her direct pass to Eurovision.

With six albums released, tours across Latin America and roles in series like Cuéntame Cómo Pasó and Arde Madrid, the singer and actress has navigated genres and formats with ease. “It’s been many years. And here we are, with a good attitude, eager to sing and keep making the audience happy. What more could you ask for?” the performer of “Parapapá” and “Rúmbame” says with a laugh.

Meanwhile, she continues to bring her music across Europe as part of her pre-Eurovision tour, TheDIVAXperience. In recent days, she has performed in Amsterdam and London, presenting the new version of “Esa Diva” to specialized media and Eurovision fans. On April 7, the artist was welcomed in Dos Hermanas, her hometown, where she performed the song from the balcony of City Hall before a crowd. “The love from my hometown moves me. When you’re recognized at home, it feels different,” she says.

This week, she will participate in the PrePartyES in Madrid (April 18-19), where she will share the stage with representatives from various European delegations. Then, on April 23, she will headline a special farewell event organized by RTVE at Teatro Barceló before heading to Basel for the contest.

The staging for Eurovision promises a significant evolution compared to what was seen at the Benidorm Fest. Melody has indicated that the set design will include new visual and choreographic elements, aiming to make the most of the technical possibilities of the stage. “There will be new ingredients. It won’t just be a song; it’s a story I want to tell,” she says, making it clear that her proposal seeks to move audiences beyond the visual spectacle.

Recently becoming a mother, Melody, an independent artist and an advocate for meaningful lyrics, acknowledges that balancing it all is not easy: “I organize myself however I can. But my son recharges my batteries, and when I need grounding, I go back home.” Participating in Eurovision involves much more than stepping onto a big stage — it means enduring a level of media exposure, artistic pressure, and public scrutiny that is hard to match.

Regarding the flood of opinions surrounding this experience, Melody maintains a firm stance. “I value constructive criticism; there’s always room to learn. But destructive criticism doesn’t affect me. I’m not driven by that. I sing from the heart, and that’s why I’m here,” she says.

Her approach is not casual. Eurovision generates a massive volume of social media conversations every year, with millions of interactions, according to data from the EBU (European Broadcasting Union). The contest’s global audience exceeds 160 million viewers across its three shows, making it one of the most-watched musical events in the world. For any artist, the exposure is as immense as the challenge.

After the festival, Melody already has plans: a new single, a tour across Spain and a strong desire to reconnect with her Latin American audience. “I’ve always felt so much love from Latin America,” she says. “This is a new chapter, and I’m thrilled to bring my music there again. They’re so heartfelt, so close. I want to dance and enjoy together.”

Wiz Khalifa delivered.

15 years after he dropped his classic Blog Era mixtape Kush & Orange Juice, the multi-platinum rapper decided to go back to his roots on its sequel tape and tap back into the sound that made him one of stoner rap’s most important rappers. He also brought the gang back together as Cardo, Sledgren and his stoner-in-crime Curren$y all contributed like they did during that first cypher back in April of 2010.

Kush & Orange Juice 2 also features the likes of Gunna, Mike WiLL Made-It, Ty Dolla $ign, Don Toliver, Larry June, Conductor Williams, and legends in Juicy J, DJ Quik, and Max B, among others. And while those acts are diverse in terms of their own individual sounds, Wiz was able to have them fit the story he wanted to tell and he did a pretty good job. It’s rare if not damn near impossible for a sequel to be as good as a classic, but Wiz did a pretty good job. Clocking in at 23 tracks and 77 minutes long, the Kush & OJ sequel is the perfect soundtrack for that cousin walk on Easter Sunday — as you and your family celebrate not only the resurrection, but 4/20 as well.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

And as he rolled out the much anticipated project, Khalifa went on an already-memorable run of freestyles that started last November with “First YN Freestyle.” Hopefully more rappers will hop on that wave, and give fans more music that feels fun and low-stakes.

Trending on Billboard

Billboard talked with Wiz about why he decided to take that approach, and about a bunch of other things. Check out our chat below and be sure to go run up that Kush + Orange Juice 2 this weekend.

You’ve been on a crazy run lately with these freestyles. Can you talk about why you decided to go that route?

Really just by seeing the reaction of my fans and the people who support me when I started to get into the mode of promoting Kush & Orange Juice 2, and really visualizing what that was going to feel like for everybody else. I wanted to make it an experience, and not something that just dropped overnight and then went away. So, me doing the freestyles was kind of a way to write that narrative and to get everybody on board so they understand what to expect and it got a great reaction. So, naturally, I just kept going. And it’s something that I like to do just for fun.

Did the freestyles help spark something creatively in you?

I was already pretty much done with the album by the time I did the freestyles. But I think anytime I’m able to just play around and see what people enjoy, it gives me a sense of what to do next or what to continue doing. So, it definitely served its purpose when it comes to that.

You and other Blog Era peers like J. Cole, Kendrick Lamar and Drake have crossed over into the mainstream. So, now that you’ve achieved a certain level of success, does that mean that you plan on still playing the major-label game, or are you gonna go back to just making what you feel like making?

I think it all just kind of comes together, and it’s really about the fans and what they want and what people are are tuning into, and just me knowing that people digest my music for the way that I do it. It allows me to be free, but it also opens up a lot of different opportunities for me to put that in other places. So, it’s a beginning of a wave that could, you know, go on for however long.

Why do you think rappers have moved away from doing freestyles and stuff like that?

I think because clearances and a lot of people want their their stuff on the biggest platform. It’s hard to monetize a freestyle and if you put a lot of energy into it, a lot of people want it to go far, so that value has been missing. It takes certain artists to push it and to show that the value of it isn’t gone. It’s not really where you’re aiming to put these at. The people and the listeners, and their ears are there, and they’re going to discover it. I think people have to re-understand that and reimagine that.

So much has changed since you came in the game. If you were an up and coming rapper today, how would you approach your career?

I would approach it the same way. A lot of the younger artists or personalities, they know who their fan base is. They know who they’re talking to, and they reach out to them, and that’s what dictates what they do or what their next moves are. And a lot of artists are afraid of that, but there’s a lot of power and a lot of value in knowing who your consumers are and the people who want the best from you and aiming what you do towards them. And that would be my advice, or that would be what I would do. That’s what I’m doing now, is just focusing on the people who I know support and are expecting this, and really just making the experience for them.

One person that’s carving out a unique lane for themselves is streamer and producer PlaqueBoyMax. You were on his stream recently. How was that experience?

Yeah, it was cool working with Max, and that was the first time I had made a song live on somebody else’s stream. And even just with that platform of him being, you know, with FaZe and them having the reach that they do. That’s a whole different fanbase than the people who are used to me, and it was good to be able to win those people over, show them what my talent actually is, and work with somebody for the first time and create something in front of everybody that’s just super fun and super cool to me.

You floated the idea of doing a full tape with him towards the end. Do you think that can happen down the line?

I wanted to do it, but I feel like he’s already doing it, and he’s doing it in his way, where he’ll benefit off of it, which is cool with me. I’m always down anytime. If he needs me, then he’ll hit me.

What can fans expect from Kush & Orange Juice 2?

They can expect good smokin’ music, good chillin’ music, good motivational music, and good ridin’ around with the homies music. It’s definitely for the people who understand it. And it’s not just about the music, it’s about the experiences that you have with it. So, the more you listen to it and live with it, or even if it’s your first time, when you listen to it and live with it, it’s gonna change a lot. I’m really happy with that. I’m really confident in that, and I’m just really excited for everybody to experience that.

Are you performing anywhere on 4/20?

Yeah, I’m gonna be performing at Red Rocks in Colorado.

I interviewed Curren$y a couple months ago, and I had asked him if he has any 420 rituals and he said he doesn’t really have any because he’s always working. I’m assuming that’s the same for you.

Yeah, pretty much, especially at this point. A lot of people come out and visit us on those days, even if it’s family from the East Coast or an artist or whatever. They usually want to come kick it with us, so that’s usually fun. I get to see a lot of people who I just really enjoy smoking with, like Berner. It is work, but for me personally, I try to roll at least an abnormally big joint or two, and I usually smoke more dabs that day than I normally do as well.

I wanted to ask you what your favorite strains were, but on Club Shay Shay, you said you’ve been smoking your own strain exclusively for about 10 years now.

Oh yeah, it’s definitely Khalifa Kush always for like almost 12 now.

What is that like, though — having your own strain and not really having to pay for it anymore?

It’s a blessing. I don’t know if I necessarily knew that it was going to be this way. We always hoped and wished that it would be this way — and knew that it was, you know, beneficial for everybody — but to actually live in an era where we can do this… It’s awesome. I’m grateful and I’m taking full advantage.

You also mentioned the Smoke Olympics. What would be some of the events if you were to put that together?

There would be a rolling competition. I’m bringing the origami, I’m bringing the samurai skills. What else? You have to hit, like, a bong. You’ll have to make a bong out of something. You could choose what you have to make a bong out of. You have to last a certain amount of rounds, too — so as we keep smoking, there’s no tapping out. Yeah, we’ll start there.

I ran into Conductor Williams recently and he was beaming about the way you approached “Billionaires” with Ty Dolla $ign. What was it about that particular beat that caught your attention out of the pack of beats that he sent?

I appreciate it. I feel like I always gravitated towards his production because of how soulful it is and just how musically inclined he is. You could tell he knows a lot about music in general. My approach is very specific to what I know my people are gonna f—k with. And I think when I got into that pocket, it was nostalgic, but it was also something that people never expected, or ever knew that they would enjoy.

I think that combination right there kind of makes discovering some new music worth it — and that’s what people need now, and to be able to do that with people who I’m cool with, and got in my phone and I can hit at whatever time, and be like, “Yo, send me some beats,” and we could just come up with something legendary off the bat. That’s real fun for me.

You’ve gotten into martial arts like over the years like Muay Thai and Jiu Jitsu. How important has that been for you?

It’s part of my everyday life as much as music is and I’m passionate about it the same way I am about my music, and I’ve been doing it for seven years now, and I feel like I’m still learning a lot of new things, and it’s still fun and it’s interesting. It’s not a chore or a job or I don’t even have a real end goal when it comes to it, so it’s fun to be on a journey and have something that I that I enjoy and that challenges me and also makes me better.

Has it helped your lungs be stronger too?

Yeah, 100 percent. My cardio is crazy, and it helped me learn how to control my breathing better and just being in good shape in general. Being able to function and and move athletically as I get older, because I’m 37 now, so I’m moving into my 40s. The older that we get the less athletic some of us get. But for me, it’s a lifetime thing of I’m always going to have this type of movement.

At the end of last year, Bobby Pulido announced his retirement from music to pursue a career in politics starting in 2026. But the norteño-tejano music icon still has much to offer.

In an exclusive interview with Billboard Español, Pulido reveals that he has signed with Fonovisa/Universal for a double album and an additional new project he’ll release before officially closing his chapter as a singer.

“I wanted something special with my friends, something where I could invite the people I admired and respected,” Pulido explains about Bobby Pulido & Friends – Una Tuya y Una Mía, the title of the set that will kick off this partnership. “Normally, it’s customary for guests to sing the other person’s songs, but in this case, I wanted it to be one of mine and one of theirs.”

The recording took place in December 2024 during the Mexican-American singer’s performances at the Auditorio Cumbres in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico, where he was joined by guests such as Alicia Villarreal, Bronco, Kinky, Caloncho, Majo Aguilar and David Bisbal, among other stars.

Trending on Billboard

The concept will begin to unfold on April 22 with the release of Pulido’s hit “Desvelado” in a duet with Bisbal. Two days later, a norteño-tejano version of the Bisbal’s song “Dígale” will be available on streaming platforms.

Antonio Silva, managing director of Fonovisa Disa US & México, tells Billboard Español: “For the team and personally for me, having worked with him at the start of his career, it’s very emotional to reunite at such a special moment, working on a product that represents the legacy of a lifetime of success.”

The first part of Bobby Pulido & Friends – Una Tuya y Una Mía includes 14 songs that will be released in pairs on a weekly basis, starting on April 22 and continuing until May 30. Starting June 17, the 16 songs of the second set will begin to launch, concluding on Aug. 7.

L to R: Antonio Silva (managing director Fonovisa-Disa US/México), Bobby Pulido, Alfredo Delgadillo (CEO & president, Universal Music México/US), José Luis Cornejo (manager Bobby Pulido)

Fonovisa/Universal

Born in Edinburg, Texas, Pulido — the performer of hits like “Se Murió de Amor,” “Le Pediré” and “Ojalá Te Animes” — belongs to a successful subgenre of regional Mexican music that emerged in the mid-’90s and includes groups like Intocable, La Firma, El Plan, and Duelo — all U.S.-born with Mexican roots. “We made our own music by blending cultures. I feel very honored to have represented this movement for so many years and to mentor new generations,” Pulido adds. “I’m happy with what I’ve achieved in my career. I never wanted to be just the artist of the moment.”

In addition to the double set, Pulido is preparing a studio album for next year, aiming to leave new music for his fans before running for an unspecified public office in Texas.

Fans will still have the chance to see Pulido live throughout 2025 during his Por La Puerta Grande Tour, which kicks off on April 25 in San Antonio, Texas. The trek includes a show on Aug. 9 at the Auditorio Nacional in Mexico City. For more dates and details, click here.

HipHopWired Featured Video

Dee-1 has always been positioned as a Hip-Hop artist with a message, and few have shown the level of conviction and criticism that he has for the music and culture of Hip-Hop. While attending Dreamville Festival last weekend, Dee-1 graciously gave us a few minutes of his time and shared details of his upcoming album, Hypocritical Hop.

While backstage at the Dreamville Festival, Dee-1’s towering frame and his always observant stance stood out, and as we approached him for questions, we asked what brought him to the festival.

“One of the things I’ve learned as an artist is the power of networking,” he began. “Getting out there helps because people can see my face and hold a conversation with me, and that helps in turn with the other work that I do.”

The former schoolteacher turned musical artist then explained the similarities of leading the youth in the position of guidance and leadership, and how that translates into his current role as a front-facing media figure.