Copyright

Page: 5

Paul McCartney is speaking out against proposed changes to copyright laws, warning that artificial intelligence could harm artists.

The British government is currently considering a policy that would allow tech companies to use creators’ works to train AI models unless creators specifically opt out. In an interview with the BBC, set to air on Sunday (Jan. 26), the 82-year-old former Beatle cautioned that the proposal could “rip off” artists and lead to a “loss of creativity.”

“You get young guys, girls, coming up, and they write a beautiful song, and they don’t own it, and they don’t have anything to do with it. And anyone who wants can just rip it off,” McCartney said. “The truth is, the money’s going somewhere… Somebody’s getting paid, so why shouldn’t it be the guy who sat down and wrote ‘Yesterday’?”

The U.K. Labour Party government has expressed its ambition to make Britain a global leader in AI. In December 2024, the government launched a consultation to explore how copyright law can “enable creators and right holders to exercise control over, and seek remuneration for, the use of their works for AI training” while also ensuring “AI developers have easy access to a broad range of high-quality creative content,” according to the Associated Press.

Trending on Billboard

“We’re the people, you’re the government. You’re supposed to protect us. That’s your job,” McCartney told the BBC. “So you know, if you’re putting through a bill, make sure you protect the creative thinkers, the creative artists, or you’re not going to have them.”

The Beatles’ final song, “Now and Then,” released in 2023, utilized a form of AI called “stem separation” to help surviving members McCartney and Ringo Starr clean up a 60-year-old, low-fidelity demo recorded by John Lennon, making it suitable for a finished master recording.

As AI becomes more prevalent in entertainment, music and daily life, the debate around its impact continues to grow. In April 2024, Billie Eilish, Pearl Jam and Nicki Minaj were among 200 signatories of an open letter directed at tech companies, digital service providers and AI developers. The letter criticized irresponsible AI practices, calling it an “assault on human creativity” that “must be stopped.”

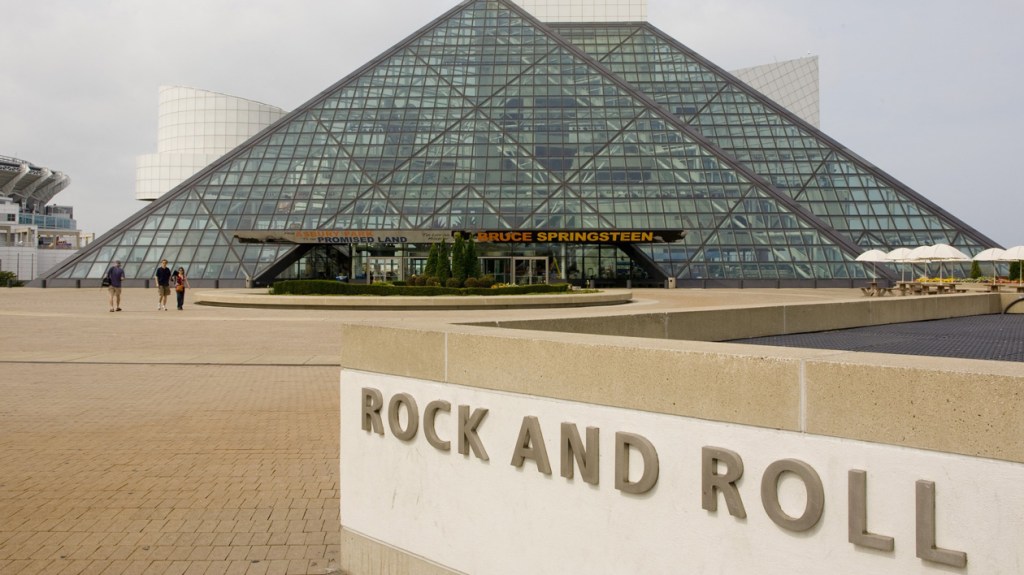

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame wants a federal judge to toss out a copyright lawsuit over an image of Eddie Van Halen, arguing that it made legal fair use of the image by using it as part of a museum exhibit designed to “educate the public about the history of rock and roll music.”

The lawsuit, filed last year, claims the Rock Hall never paid to license Neil Zlozower’s image — a black-and-white photo of late-’70s Van Halen in the recording studio — before blowing it up into an eight-foot-tall display in the Cleveland museum.

But in a motion to dismiss the case filed Tuesday (Jan. 21), the Rock Hall says it didn’t need to. Attorneys for the museum say the offending exhibit was protected by “fair use”, a rule that allows copyrighted works to be reused legally in many contexts, including education and commentary.

Trending on Billboard

“RRHOF transformed plaintiff’s original band photograph by using it as a historical artifact to underscore the importance of Eddie Van Halen’s musical instruments,” the Hall’s attorneys write. “RRHOF operates a museum, and it displayed the image in service of its charitable mission to educate the public about the history of rock and roll music.”

Zlozower filed his case in October, claiming the Hall made an “exact copy of a critical portion of plaintiff’s original image” for the exhibit, which he claimed “did not include any photo credit or mentions as to the source of the image.”

The Rock Hall is just the latest company to face such a lawsuit from Zlozower, who also snapped images of Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson and Bruce Springsteen over a decades-long career. Since 2016, court records show he’s filed nearly 60 copyright cases against a range of defendants over images of Elvis Costello, Guns N’ Roses, Mötley Crüe and more.

In the current dispute, the Van Halen image was used in two exhibits: “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll” and “Legends.” Focused on musical instruments used by famed rockers, the exhibits featured sections showing Van Halen’s guitars, amplifiers and other gear. In the display, the original photo of the band was cropped to show just Eddie holding one of the guitars, which was placed amid the exhibit’s objects and informational placards.

In their motion to dismiss the case, the Rock Hall’s attorneys say the museum made a “transformative use” of Zlozower’s original image — a key question when courts decide fair use. They say the Hall used it not simply as an image of the band, but “to contextualize Eddie Van Halen’s instruments on display in the museum as historical artifacts.”

“RRHOF incorporated a portion of plaintiff’s photograph displayed next to the exhibition object, as one piece of source material to document and represent the use of the guitar,” the museum’s lawyers write. “This proximal association between source material and exhibition object helps visitors connect information and delve more deeply into the exhibition objects.”

In making that argument, the Hall’s attorneys had a handy piece of legal precedent to cite: A 2021 ruling by a federal appeals court tossed out a copyright lawsuit against New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art over the use of another image of Van Halen in a different exhibit on the same famous set of guitars.

In making that ruling, the appeals court said the Met had clearly made “transformative” fair use of the image by displaying it alongside the exhibit: “Whereas [the photographer]’s stated purpose in creating the photo was to show ‘what Van Halen looks like in performance,’ the Met exhibition highlights the unique design of the Frankenstein guitar and its significance in the development of rock n’ roll instruments,” the appeals court wrote at the time.

That earlier ruling is not technically binding on the case against the Rock Hall, which takes place in another region of the federal court system. But such an uncannily on-point ruling could certainly be influential on the judge overseeing the current case.

An attorney for Zlozower did not immediately return a request for comment.

Travis Scott, SZA and Future are facing a copyright lawsuit over allegations that they stole key elements of their 2023 hit “Telekinesis” from an earlier track.

In a complaint filed Wednesday in Manhattan federal court, Victory Boyd (a singer signed to Jay-Z‘s Roc Nation record label) says the stars copied lyrics and other elements from her 2019 song “Like The Way It Sounds” and used them in “Telekinesis,” which spent 11 weeks on the Hot 100.

“Scott, Sza, Future and all defendants intentionally and willfully copied plaintiffs’ original work, specifically plaintiff’s lyrics, when they commercially released the infringing work,” write Boyd’s lawyers.

Trending on Billboard

Boyd claims that she initially shared “Like The Way” with Kanye West, who then recorded it as a track called “Ultrasounds.” West (who is not named in the lawsuit) then allegedly shared the song with Scott, who then shared it with SZA and Future.

“Scott gained access to the studio plaintiff left the original work in and began creating the infringing work,” Boyd’s lawyers write. “In May of 2023, Scott, SZA and Future agreed to create the infringing work by copying plaintiff’s original work.”

Notably, the lawsuit say the stars have essentially admitted to using her song. When “Telekinesis” was first uploaded to streaming platforms, Boyd’s lawyers say she was credited as a co-writer in the metadata. More recently, they say she’s been offered an 8 percent songwriting credit to resolve the dispute.

But Boyd appears focused on the fact that she “never granted permission” for her song to be used in the first place – saying the track had been taken without her “authorization, knowledge or consent.”

Also named as a defendant in the lawsuit is Audemars Piguet, a Swiss watchmaker that has partnered with Scott’s Cactus Jack brand for a collaborative line of watches. Boyd says the company used “Telekinesis” in advertising videos even after she and her publisher expressly refused their request for a license.

“The defendants and AP partnered to publish and commercially release an advertising campaign broadcasting the infringing work over the plaintiff’s objection,” her lawyers write.

The connection between “Telekinesis” and Boyd is hardly a secret. On the crowd-sourced lyrics database Genius, fans have noted that the song was “originally written by Victory Boyd as a gospel song” for West, then was “passed around many artists” before it “eventually ended up being a Travis song.”

Reps for Scott, SZA and Future did not immediately return requests for comment.

LONDON — Proposed changes to U.K. copyright law that would allow tech companies to freely use songs for AI training without permission threaten to place the country’s status as a “world music power” at risk, record labels trade body BPI has warned.

In 2024, hit records by Charli XCX, Sabrina Carpenter, Coldplay and Taylor Swift helped lift the United Kingdom’s streaming market to a record high with just under 200 billion music tracks streamed across the 12 months, up 11% year-on-year, according to year-end figures released Tuesday (Dec. 31) by BPI.

Overall recorded music consumption across streaming and physical album sales rose by a tenth (9.7%) on 2023’s total to 201 million equivalent albums, marking a decade of uninterrupted growth, reports the organization, which represents over 500 independent record labels, as well as the U.K. arms of the three majors: Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment and Warner Music Group.

Trending on Billboard

However, the success of the U.K. music business is being challenged on multiple fronts, including intensifying competition from other global markets and proposed regulations around the use of artificial intelligence (AI), says BPI.

The proposed AI guidelines were announced by the British government two weeks ago (Dec. 17) as part of a 10-week consultation on how copyright-protected content, such as music, can lawfully be used by tech companies to train generative AI models. Among them is a controversial new data mining exception that would allow developers to use copyrighted songs for AI training, including commercial purposes, but only in instances where rights holders have not reserved their rights.

BPI chief executive Jo Twist said the proposed opt out mechanism was the “wrong way to realise the exciting potential of AI” and places the U.K.’s music and creative industries at risk by allowing “international tech giants to train AI models on artists’ work without payment or permission.”

“The U.K. remains a world music power, but this status cannot be taken for granted,” said Twist in a statement accompanying Tuesday’s year-end figures. She said that in order to continue to thrive, the U.K. music business needs “a supportive policy environment that puts the focus on human artistry and enables continued investment in the next generation of British talent.”

Of the current generation, more than 20 British groups and solo acts topped the U.K. albums chart in 2024, although Charli XCX and Coldplay were the only homegrown artists in the year’s top 10 best-selling artist albums list, occupying the eighth and ninth positions with Brat and Moon Music, respectively. Veteran British American rock band Fleetwood Mac had the year’s seventh most popular album with their compilation 50 Years – Don’t Stop.

Topping the year-end albums list was Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department, which has sold over 783,000 equivalent units since its release in April – the most for any artist release in a calendar year since 2017, reports BPI. The Tortured Poets Department was one of four albums by Swift to feature among the year’s 20 biggest titles alongside 1989 (Taylor’s Version), Lover and Folklore.

In total, female artists accounted for six of the top 10 and half of the 20 biggest selling artist albums in the U.K. last year with hit releases by Sabrina Carpenter, Billie Eilish, Chappell Roan and Olivia Rodrigo helping make it a landmark year for women.

Female artists also spent an unprecedented 34 weeks at No. 1 on the United Kingdom’s official singles chart, largely driven by Carpenter, who spent 21 weeks at the top with her three hit singles: “Espresso, “Please Please Please” and “Taste.” The best-selling single in the U.K. last year was Noah Kahan‘s “Stick Season,” which topped the U.K. charts for seven weeks, followed by Benson Boone‘s “Beautiful Things.”

Vinyl helps physical album sales return to growth

In terms of formats, streaming now makes up 88.8% of music sales in the United Kingdom, a marginal 1.1% rise on 2023’s figure and more than double streaming’s share of the U.K. market six years ago, reports BPI.

Meanwhile, physical sales experienced year-on-year growth for the first time since 1994 with vinyl and CD album purchases up 1.4% to 17.4 million units. Driving the resurgence in physical formats was a 17th consecutive annual rise in vinyl album sales which grew by just over 9% to 6.7 million units, marking a three-decade high.

The year’s most popular vinyl album was Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department, which sold more than 111,000 vinyl copies, followed by a 30th anniversary reissue of Oasis‘ debut Definitely Maybe. Other top-selling vinyl titles included Eilish’s Hit Me Hard And Soft, Fontaines D.C.‘ Romance, The Cure‘s Songs Of A Lost World and Charli XCX’s Brat.

CD sales fell 2.9% year-on-year to 10.5 million units, representing a significant slowdown on the 19% drop recorded in 2022 and the almost 7% slide in sales experienced in 2023. Digital album sales dropped almost 6% to 3.3 million units.

BPI’s preliminary year-end report doesn’t include financial sales data. Instead, it uses Official Charts Company data to measure U.K. music consumption in terms of volume. The London-based organization will publish its full year-end report, including recorded music revenues, later this year.

The U.K. is the world’s third-biggest recorded music market behind the U.S. and Japan with sales of $1.9 billion in 2023, according to IFPI. It is also the second-largest exporter of recorded music worldwide behind the U.S.

Tougher competition from other international markets, including Latin America and fast-growing countries like South Korea, has seen the U.K.’s share of the global recorded music market shrink over the past decade, however.

In 2015, artists from the United Kingdom cumulatively accounted for 17% of global music streams, according to BPI export figures. That figure now stands at 10% with U.K. artists accounting for just nine of the top 40 tracks streamed in the country last year – the highest being “Stargazing” by Myles Smith at number 12.

“From Coldplay, and Charli XCX, to The Last Dinner Party, and Myles Smith, there were plenty of examples of U.K. music success stories in 2024. But there are also rising challenges for domestic talent in a rapidly changing and hyper-competitive global music economy,” said BPI’s Jo Twist.

“By meeting the growing global challenge head-on, tackling challenges around AI, copyright and streaming fraud, and encouraging consumers towards viable models, like paid streaming subscriptions, we can help to ensure that the value of British music is protected and that our industry can continue to grow and flourish at home and around the world,” she said.

≈

Music Business Year In Review

Here we go again.

On Dec. 9, the technology activist group Fight for the Future announced that 300 musicians signed an open letter denouncing the lawsuit that labels filed against the Internet Archive for copying and offering free streams of old recordings under its “Great 78” project. The letter essentially says that labels need to focus less on profit and more on supporting creators, by raising streaming service royalty rates — and partnering with “valuable cultural stewards” like the Internet Archive.

This is exactly and entirely backward. Labels have to focus on making money — they’re companies, duh — and they are always trying to raise streaming royalties in a way that would help them, as well as artists. It would help if streaming services raised prices, which they would have an easier time doing if less unlicensed music was available for free on both for-profit pirate sites and services like the Internet Archive. And one of the worst possible groups to offer advice on such matters is Fight for the Future, which has consistently opposed the kind of copyright protection that lets creators control the availability of their work.

Most people think of the Internet Archive, if they think of it at all, as the nonprofit organization that runs the Wayback Machine, which maintains a searchable archive of past and present Internet sites. But it also preserves and makes available other media — sometimes in ways that push the boundaries of copyright. After the label lawsuit against the Internet Archive was shifted to alternative dispute resolution in late July, an appeals court affirmed book publishers’ victory in their lawsuit against the organization for making electronic copies of books available without a license under the self-styled concept of “controlled digital lending.” On Dec. 4, the deadline passed for the Internet Archive to file a cert petition with the Supreme Court, making that decision final.

Trending on Billboard

It sometimes seems that part of the purpose of the Internet Archive, which was founded in 1996 by technology activist Brewster Kahle, is to push the boundaries of copyright. In 2006, Kahle sued the government for changing the copyright system from opt-in to opt-out. (His side lost in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.) Later, the Internet Archive began buying and scanning books and distributing digital files of the contents on a temporary basis, according to how many copies of the volume the organization owned. (The digital copies became unusable after a certain amount of time.) During the pandemic, it launched a “National Emergency Library” and announced it would begin lending out more digital copies than the number of physical copies of books it owned. Two months later, three major publishers and one other sued, arguing that this controlled digital lending — a theoretical model that’s not recognized in U.S. law — infringed copyright.

The Internet Archive argued that it was a library and that its digital lending qualified as “transformative use,” an aspect of the fair use exception to copyright law that in some cases allows copyrighted works to be used for a different purpose. (The thumbnail images seen in search engine results qualify as a transformative use, for example, since they are used to help users find the images themselves.) The copyright exceptions for libraries and archives are very specific, though, and it’s hard to imagine how borrowed digital copies of books are so different from the digital books that have become an increasingly important part of the publishing business. The Second Circuit Appeals Court treated the dispute as a straight fair use case — it barely mentioned the National Emergency Library — and ruled for the publishers.

“Fair use is an important part of the law, and no one would disagree,” says Maria Pallante, president and CEO of the Association of American Publishers, the trade group that handled the lawsuit. “But this this was a gross distortion of fair use — they wanted to normalize that it’s OK to reproduce millions of works.”

The label lawsuit — Sony Music, Universal Music Group and Concord sued under the auspices of the RIAA — could end up being just as straightforward. (Kahle is also personally named in the lawsuit, along with other entities.) The Great 78 Project makes 400,000 recordings digitized from 78 rpm records available to stream online. The idea is to “make this less commonly available music accessible to researchers,” according to the project’s web site.

The reality, the labels’ lawsuit alleges, is that among the recordings available are Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas,” Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven” and Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing),” all of which have considerable commercial life on streaming services. “The Internet Archive’s ‘Great 78’ project is a smokescreen for industrial-scale copyright infringement of some of the most iconic recordings ever made,” RIAA chief legal officer Ken Doroshow said in a statement. The Internet Archive did not respond to a request for comment.

The Internet Archive seems to be appealing both of these cases to magazines, making the case that the $621 million RIAA lawsuit threatens “the web’s collective memory” (Wired) and the “soul of the Internet” (Rolling Stone). Maybe. But neither book publishers nor labels object to the Internet Archive’s actual archive of the actual Internet. In both pieces, Kahle positions himself as a librarian and a preservationist, never mind that “White Christmas” doesn’t need preserving and that the Music Modernization Act has a provision that allows libraries to offer certain unavailable pre-1972 recordings if they follow a process. (The labels’ complaint says the organization didn’t do this; Kahle told Rolling Stone that “we talked to people, it wasn’t a problem.”) The fact that some of the recordings are scratchy, which Kahle and his allies make much of, is legally beside the point.

It’s reasonable to hope that the labels don’t put the Internet Archive out of business, because the Wayback Machine is so valuable. But it’s also reasonable to wonder why Kahle let the Internet Archive take such big legal risks in the first place. If the Wayback Machine is so important, why distribute books and music in a way that could be found to infringe copyright, with the enormous statutory damages that come with that? Unless, of course, that’s actually part of the organization’s work in the first place.

Some of these issues can get pretty abstract, but the way they’re settled could have serious consequences in the years to come. If one wanted to assemble a collection of scanned books in order to train an artificial intelligence, one might go about it in exactly the way Kahle did. Same goes for old recordings. Indeed, artificial intelligence companies are already arguing that mass copying of media doesn’t infringe copyright because it qualifies as “transformative,” and thus as fair use. There is no evidence that the Internet Archive copied books and recordings for this reason, but it’s certainly possible that the organization might have wanted to set precedents to make it easier for AI companies to argue that they use copyrighted work for training purposes compensating rightsholders.

The letter from Fight for the Future points out that “the music industry cannot survive without musicians.” But there’s a chance that the kind of large-scale copying of music that it’s convincing musicians to defend could represent a first step toward the technology business doing exactly that.

The value of global music copyright reached $45.5 billion in 2023, up 11% from the prior year, according to the latest annual industry tally by economist Will Page. When Page first calculated the value of various music copyright-related revenue streams in 2014, the figure was $25 billion—meaning music copyright could double in value in ten years.

Record labels represented the largest share of global music copyright with $28.5 billion in 2023, up 21% from 2022. Streaming grew 10.4% and accounted for the majority of labels’ revenue. Physical revenues fared even better, rising 13.4%, while vinyl record sales improved 15.4%. Globally, vinyl is poised to overtake CD sales “soon,” Page says. CD sales are still high in Japan and across Asia, but Page points out that vinyl is selling more units at increasingly higher prices. “It’ll easily be a $3 billion business by the next [summer] Olympics” in 2028, he says.

Collective management organizations that collect royalties on behalf of songwriters and publishers had revenue of $12.9 billion, up 11% from the prior year. In a sign of shifting economic influence, live performances now pay more to CMOs than general licensing for public performances. Additionally, CMOs’ digital collections exceeded revenues from broadcast and radio, reflecting the extent to which streaming has usurped the power of legacy media. A decade ago, digital made up just 5% of collections while broadcast accounted for half.

Trending on Billboard

In another shift in the industry’s power dynamics, publishers collected more revenue from direct licensing than they received from CMOs. These royalties are a combination of “large and broadly stable income like sync and grand rights and fast-growing digital income,” says Page. “Publishers prefer direct licensing as it means they see more money faster,” he explains. A song that spikes in mid-March, for example, takes 201 days to pay the artist and 383 days to pay the songwriter. “What’s more,” he adds, “a third of that [songwriter] revenue can disappear in transaction costs” in the form of administration fees charged by various CMOs.

While some parts of music copyright suffered during the pandemic—namely public performance revenue—music has surged since 2020 to overtake the brick-and-mortar movie business. In 2023, music was 38% larger than cinema. That marked a massive shift since pre-pandemic 2019, when cinema was 33% bigger than music. Over the last four years, music grew 44% while cinema shrank 21%. The true difference between music and cinema is even greater: Page’s music copyright numbers account for trade revenue that goes to rights holders and creators. The cinema figures in his head-to-head comparison represent consumer spending. Of cinema’s $33.2 billion in box office revenues in 2023, only half goes to distribution, according to one analyst’s estimate.

Page’s report covers the totality of revenue generated by both master recordings and musical works. He removes double-counting — mechanical royalties that are counted as revenue by both record labels and music publishers, for example — and fills in the gaps in more focused industry tabulations by the IFPI, CISAC and the International Federation of Music Publishers.

“Anyone trying to capture the attention of policymakers who doesn’t grasp the threat posed by AI, for example, may find it handy to have a big number showing what’s at stake,” he wrote in the report.

For large, Western music companies, the globalization of music has opened new markets to their repertoire. Page’s report looks at the reverse effect: the value of developed streaming markets to artists in less wealthy countries. North America and Europe, regions dominated by subscription revenue, accounted for 80% of the value of streaming growth but just 48% of the increase in the volume of streaming. In contrast, Latin America and Asia (less Japan), where streaming platforms get far less revenue from each listener, accounted for 12% of streaming’s value growth compared to 46% of its streaming activity gains.

To artists from Latin America and Asia, fans in markets where streaming royalties are higher can be lucrative. For example, the nearly $100 million of streaming revenues generated by Colombian artists such as J. Balvin and Shakira inside the U.S. was six times greater than those streams would have been worth in their home country. This “trade-boost” of $78 million was worth more than the entire $74 million Colombian recorded music industry. Similarly, Mexican artists’ streams inside the U.S. were worth $350 million in 2023—$200 million more than had those streams come from Mexico.

“Let’s remember, Mexico and Colombia are just two examples exporting to just one market,” says Page, who co-authored a paper in 2023 that described the rise of “globalization,” a term for music created for local markets in native languages that tops local charts on global streaming platforms. “There’s so many more across South and Central America and the whole world is listening to these new ‘glocalisatas’.”

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is facing a lawsuit over allegations that it illegally displayed a copyrighted image of Van Halen, the latest of more than 50 such cases filed by veteran rock photographer Neil Zlozower over the past decade.

In a complaint filed Friday in Ohio federal court, attorneys for the litigious photog say the Rock Hall never paid to license Zlozower’s image – a black-and-white photo of late-70’s Van Halen in the recording studio — before blowing it up into an eight-foot-tall display in the Cleveland museum.

In his lawsuit, Zlozower says that an operation like the Hall, which is full of copyrighted images and sound recordings, ought to have known better.

Trending on Billboard

“Defendant is a sophisticated company which owns a comprehensive portfolio of physical and digital platforms and has advanced operational and strategic expertise in an industry where copyright is prevalent,” his lawyers write. “Defendant’s staff have significant experience in copyright matters and are familiar with specific practices including the need to ensure that all of the works used in their exhibits have been properly licensed.”

A spokesman for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame did not immediately return a request for comment.

The Rock Hall is just the latest company to face a lawsuit from Zlozower, who also snapped images of Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson and Bruce Springsteen over a decades-long career. Since 2016, court records show he’s filed more than 57 copyright lawsuits against a wide range of defendants, demanding monetary damages over the alleged unauthorized use of his photographs.

He’s twice sued Universal Music Group, once over an image of Elvis Costello and another time over a photo of Guns N’ Roses, and sued Warner Music Group this summer over an image of Tom Petty. A different case targeted Ticketmaster, accusing the Live Nation unit of using an image of Ozzy Osbourne guitarist Zakk Wylde. In 2016, Zlozower sued Mötley Crüe itself for using images he had snapped of Nikki Sixx, Tommy Lee and other band members during their 1980s heyday.

In his new case against the Rock Hall, Zlozower’s attorneys say the museum made an “exact copy of a critical portion of plaintiff’s original image” for the exhibit, which they say “did not include any photo credit or mentions as to the source of the image.”

“The photograph was willfully and volitionally copied and displayed by defendant without license or permission, thereby infringing on plaintiff’s copyrights in and to the photograph,” the lawsuit reads.

The lawsuit is seeking an award of so-called statutory damages – which can potentially reach as high as $150,000 per work infringed if Zlozower can prove that the museum intentionally infringed his copyrights.

Ice Spice has reached an agreement to end a copyright lawsuit over allegations that her recent hit “In Ha Mood” was copied from a Brooklyn rapper’s earlier track.

The case, filed earlier this year by a rapper named D.Chamberz (Duval Chamberlain), claimed that Ice Spice’s song – which spent 16 weeks on the Hot 100 in 2023 – was “strikingly similar” to his own 2021 track “In That Mood.”

But in a motion filed in federal court Friday, attorneys for both sides said they had agreed to resolve the lawsuit. Specific terms of the deal were not disclosed in court filings, and neither side immediately returned requests for comment.

Trending on Billboard

Released early last year following Ice Spice’s 2022 breakout, “In Ha Mood” reached No. 58 on the Hot 100 and No. 18 on the US Hot R&B/Hip Hop Songs chart. It was later included on her debut EP Like..?, and she performed the song during her October appearance as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live.

In a lawsuit filed in January, D.Chamberz claimed that the two songs share so many similarities that the overlaps “cannot be purely coincidental.” He said the similar elements “go [to] the core of each work,” and are so obvious that they’ve already been spotted by listeners.

“By every method of analysis, ‘In Ha Mood’ is a forgery,” D.Chamberz’s attorneys wrote at the time. “Any proper comparative analysis of the beat, lyrics, hook, rhythmic structure, metrical placement, and narrative context will demonstrate that ‘In Ha Mood’ was copied.”

The lawsuit claimed the earlier song received “significant airplay” on New York City radio stations, including Hot 97 and Power 105.1, giving Ice Spice and others behind her track a chance to hear it.

In addition to naming Ice Spice (Isis Naija Gaston) as a defendant, the lawsuit also names her frequent producer, RiotUSA (Ephrem Lopez, Jr.), as well as Universal Music Group, Capitol Records and 10K Projects.

In April, the defendants formally denied the lawsuit’s allegations, but the case remained in the earliest stages when Friday’s agreement was reached.

Decades after Nelly released his chart-topping breakout Country Grammar, he’s facing a new lawsuit over the album from his St. Lunatics groupmates – who claim that the star cut them out of the credits and the royalty payments.

In a complaint filed Wednesday in Manhattan federal court, attorneys for the St. Lunatics allege that Nelly (Cornell Haynes) repeatedly “manipulated” them into falsely thinking they’d be paid for their work on the 2000 album, which spent five weeks atop the Billboard 200.

“Every time plaintiffs confronted defendant Haynes [he] would assure them as ‘friends’ he would never prevent them from receiving the financial success they were entitled to,” the lawsuit reads. “Unfortunately, plaintiffs, reasonably believing that their friend and former band member would never steal credit for writing the original compositions, did not initially pursue any legal remedies.”

Trending on Billboard

The case was filed by St. Lunatics members Ali (Ali Jones), Murphy Lee (Tohri Harper), Kyjuan (Robert Kyjuan) and City Spud (Lavell Webb). Slo Down (Corey Edwards), another former member of the group, is not named as a plaintiff.

A spokesperson for Nelly did not immediately return a request for comment.

A group of high school friends from St. Louis, the St. Lunatics rose to prominence in the late 1990s with “Gimme What U Got”, and their debut album Free City – released a year after Country Grammar – was a hit of its own, reaching No. 3 on the Billboard 200.

The various members of the group are repeatedly listed as co-writers in the public credits for numerous songs on Country Grammar, most notably with City Spud credited as a co-writer and co-performer on the single “Ride Wit Me,” which spent 29 weeks on the Hot 100.

In the new lawsuit, the group members say they were involved with more songs than they were credited for, including “Steal the Show,” “Thicky Thick Girl,” “Batter Up,” and “Wrap Sumden.” The most notable is the title track “Country Grammar,” which reached No. 7 on the singles chart; in public databases, the song only credits Nelly and producer Jason Epperson.

The groupmates say that during and after the Country Grammar recording session, Nelly “privately and publicly acknowledged that plaintiffs were the lyric writers” and “promised to ensure that plaintiffs received writing and publishing credit.” But decades later, in 2020, the St. Lunatics members say they “discovered that defendant Haynes had been lying to them the entire time.”

“Despite repeatedly promising plaintiffs that they would receive full recognition and credit… it eventually became clear that defendant Haynes had no intention of providing the plaintiffs with any such credit or recognition,” the group’s attorneys write.

When the group members realized Nelly had “failed to provide proper credit and publishing income,” they say they hired an attorney who reached out to Universal Music Publishing Group. The letter was relayed to Nelly’s attorneys, who they say “expressly repudiated” their claims to credit in 2021.

“Plaintiffs had no alternative but to commence legal proceedings against Defendants,” the lawsuit reads.

The case could face an important procedural hurdle. Although copyright infringement lawsuits can be filed decades after an infringing song is released, disputes over copyright ownership face a stricter three-year statute of limitations.

The current lawsuit is styled as an infringement case, with the St. Lunatics alleging that Nelly has unfairly used their songs without permission. But the first argument from Nelly’s attorneys will likely be that the case is really a dispute over ownership – and thus was filed years too late.

An attorney for the plaintiffs did not immediately return a request for comment.

Ye (formerly Kanye West) has reached a settlement in a copyright lawsuit that accused him of using an uncleared sample from the pioneering rap group Boogie Down Productions in his song “Life of the Party.”

In court documents filed Monday, attorneys for both sides agreed that Ye should be dismissed from the case, with each side to pay their own legal bills. No other terms of the agreement were disclosed publicly, and neither side immediately returned requests for comment.

The Boogie Down lawsuit was one of more than a dozen such cases that have been filed against Ye over claims of unlicensed sampling or interpolating during his prolific career. The controversial rapper has faced nine such infringement cases since 2019 alone, including a high-profile battle with estate of Donna Summer that settled earlier this year.

Filed in November 2022, the current lawsuit was lodged by Phase One Network, the group that owns Boogie Down’s copyrights, over allegations that Ye had used incorporated key aspects from the 1986 song “South Bronx” into “Life of the Party,” which was released on his 2021album Donda.

Trending on Billboard

Echoing several other sampling lawsuits against Ye, Phase One claimed that the rapper’s representatives had reached out to legally clear the use of the Boogie Down song – but then released it anyway when a deal was never struck.

“The communications confirmed that ‘South Bronx’ had been incorporated into the infringing track even though West had yet to obtain such license,” Phase One’s lawyers wrote. “Despite the fact that final clearance for use of ‘South Bronx’ in the infringing track was never authorized, the infringing track was nevertheless reproduced, sold, distributed, publicly performed and exploited.”

Last summer, attorneys for Ye fought back with an unusual argument: That Boogie Down founder KRS-One had publicly promised all future rappers that “you will not get sued” over sampling the group’s catalog. They cited a 2006 documentary called The Art of 16 Bars, in which KRS-One said “I give to all MCs my entire catalogue.”

Phase One later called that a “bizarre argument,” noting that, when the documentary was made, KRS-One didn’t actually own the music he was claiming to place in the public domain: “Movants cite to no law to support such a theory. KRS-One also could not have placed the Work in the public domain as he did not own it.”

Following Monday’s agreement, Ye and his Yeezy LLC will be dropped from the lawsuit but the case will continue against other several defendants, including the company behind the Stem Player platform on which the song was allegedly released.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio