Classical

Universal Music Group has announced the expansion of two of its most storied labels — Deutsche Grammophon and Blue Note Records — into greater China, marking a significant move to tap into the country’s rapidly growing classical and jazz music scenes.

“At UMG, we are committed to supporting the development of diverse music cultures around the world,” said Adam Granite, UMG’s executive vice president of market development. “The launch of Deutsche Grammophon China and Blue Note Records China reflects this vision in action and marks a meaningful step forward in the evolution of our multi-label operations in the market.”

Announced at an event in Shanghai this week, Deutsche Grammophon China will focus on discovering and promoting new classical talent across China, plus provide artists with access to UMG’s global resources, including recording, international promotion and touring. Chinese musicians Lang Lang, Yuja Wang and Long Yu will serve as artistic advisors, guiding the label’s artistic direction.

Trending on Billboard

DG China’s debut release, Bach: The Cello Suites by acclaimed cellist Jian Wang, is set for May 23. Additionally, DG China will collaborate with the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra to record and release the complete Shostakovich Symphonies by 2029, celebrating the orchestra’s 150th anniversary.

Dr. Clemens Trautmann, president of Deutsche Grammophon, highlighted the label’s growing presence in China over the past decade and noted that the partnership with Blue Note and the involvement of international artists underscore UMG’s global reach and creative ambition. “We are proud to co-invest in the future generation of outstanding classical performers from Greater China, together with our esteemed colleagues at UMGC to foster the success of amazing new talent across recording, touring and brand partnerships,” Trautmann said.

Stacy Yang, Timothy Xu, Dr Clemens Trautmann and Adam Granite in Shanghai.

Courtesy Photo

Blue Note Records China is set to champion original jazz talent within the country, beginning with its inaugural signing: INNOUT, an avant-garde duo known for fusing improvisation, modern jazz, and experimental soundscapes. This partnership underscores the label’s commitment to bold, boundary-defying artistry.

BNRC is also partnering with JZ Music, a key player in China’s jazz scene, to promote live performances, tours, and festivals.

Don Was, president of Blue Note Records, praised INNOUT’s visionary talent and expressed excitement about launching the label’s Chinese chapter with their music. “Xiao Jun and An Yu are two of the most talented and visionary musicians I’ve ever met,” Was said. “Their music is going to ‘blow people’s minds’ all over the world. It’s a thrill and an honor to be able to launch Blue Note Records China with their music.”

Dave Grohl made a surprise appearance during weekend two of Coachella 2025.

On Saturday (April 19), the Foo Fighters frontman took the stage with his guitar to join Venezuelan maestro Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic for powerful orchestral renditions of Foos songs “The Sky Is a Neighborhood” and “Everlong” at the Outdoor Theatre of the Indio, Calif., music festival.

The occasion marked Grohl’s first time performing Foo Fighters tracks since revealing last fall that he had fathered a child outside his marriage.

“I love my wife and my children, and I am doing everything I can to regain their trust and earn their forgiveness,” the musician shared in a September 2024 Instagram post.

Trending on Billboard

In the months since, Grohl has returned to the stage for several high-profile appearances, including performances with former Nirvana bandmates Krist Novoselic and Pat Smear — joined by guest vocalists — at the FireAid LA Benefit Concert in January and the SNL50: The Homecoming Concert in February.

Grohl wasn’t the only surprise during Saturday’s star-studded Coachella set. Wicked actress Cynthia Erivo, who plays Elphaba opposite Ariana Grande’s Glinda in the live-action adaptation of the Broadway musical, also appeared to perform what is believed to be “Brick by Brick,” a ballad from her forthcoming sophomore album, I Forgive You, according to Rolling Stone.

Erivo followed up with a soulful rendition of Prince’s “Purple Rain.” “Hello Coachella, nice to see you. Would you like a little Prince?” she asked the crowd, who erupted in cheers. “OK, Prince for you then.”

Other guest performers included Natasha Bedingfield, who sang her 2004 hit “Unwritten,” as well as Laufey and Argentine duo Paco Amoroso and Ca7riel.

Dudamel and the LA Phil made their Coachella debut during weekend one on April 12, with an eclectic lineup of special guests including Becky G and LL Cool J. This appearance marks a historic moment for the orchestra, as it’s their first time performing at the festival. The 2025–2026 season will also be Dudamel’s final year as music and artistic director of the LA Phil.

Weekend two of Coachella wraps up Sunday with performances by Post Malone, Travis Scott, Megan Thee Stallion, JENNIE, Zedd, Kraftwerk, and more.

Billboard Japan’s Women in Music initiative launched in 2022 to celebrate artists, producers and executives who have made significant contributions to music and inspired other women through their work, in the same spirit as Billboard’s annual Women in Music honors since 2007. This interview series featuring female players in the Japanese entertainment industry is one of the highlights of Japan’s WIM project.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

The latest installment of the series features Aimi Kobayashi. The 29-year-old classical pianist first performed with an orchestra when she was seven and made her international debut when she was nine. In 2021, she came in fourth place in the International Chopin Piano Competition, attracting attention from around the world. In November 2024, she released her first new album in three years after taking maternity and childcare leave. On behalf of Billboard Japan, the writer Rio Hirai spoke with Kobayashi, who shared her current mindset as she continues to advance her career while enjoying the major changes in her life.

You’ve built a career as a pianist, garnering international attention from a young age. Has your approach to music changed since you got married and became a mother in 2023?

Trending on Billboard

Aimi Kobayashi: My approach to music hasn’t really changed. Of course, the way I use my time has changed dramatically since becoming a mom. I have an adorable little monster at home, so it’s tough to find time to practice for concerts. But when I see how cute my child is, that alone makes me feel like working hard again.

So even after the stage in your life has changed, you continue to be committed to music. Still, there must be difficulties in continuing your career while parenting.

There are many other difficult things in life besides childbirth. So you just have to adapt to the situation you find yourself in and get on with it. You get used to the situation and it becomes the norm, so you don’t have to think too much about it and just do what’s in front of you, thinking “I have to get it done somehow!” I do my best with housework and parenting, but I don’t expect to be perfect at everything. I’m pretty casual about everything except my job. I think the secret to continuing your career is to get help from the people around you like your parents and set up a support system.

Were you good at relying on other people before you became a mom?

No, I was the type who couldn’t rely on others. But after having a baby, I found myself thinking more often that you can’t live on your own, so I started relying on people around me without hesitation. I’m a mom, but don’t think I have to raise my child on my own. Of course I feel that I have to protect my child, but both the mother and father should equally fulfill their parental roles. You share the housework and childcare with your partner, and if that’s still too much, you can ask for help from other people and raise your child together.

That’s true. When you were in your teens or early twenties, did you ever feel anxious about balancing work with marriage and parenting?

No! I didn’t intend to give up either. I think it’s possible to balance both depending on who you marry. I wanted to be a pianist even after I got married and became a mom. That’s why I wanted to marry someone who would understand and support my career.

When you were 17, you took a break from playing in concerts and went to study at The Curtis Institute of Music in the U.S. Did you feel differently then, compared to during your recent maternity and parental leave?

During my time abroad, I only took a break from doing concerts and continued to practice improving my skill, so it felt completely different. As for maternity and parental leave, it was the first time in my musical career that I took a real break. It’s not often that you get a break that everyone around you congratulates you on. I really enjoyed raising our child and doing the housework while waiting for my partner to come home. But as it continued, I really started to feel the desire to go back to work. My partner continued to perform at concerts, so there were times when I felt anxious and wondered, “When will I be able to get back to work?”

I see. How did you overcome that anxiety?

I decided to push my comeback back two months, and that was a big relief. I had concert plans and other things lined up, and had initially decided to return to work as soon as possible because I didn’t want to cancel or postpone. I’d never experienced any major illnesses and was in good health, so I thought I’d be able to manage it if I just worked hard, but giving birth was harder than I’d expected. Even so, I still thought I had to return as soon as possible and ended up getting sick and feeling mentally overwhelmed. Then, the people at my agency and my manager told me, “Your mind and body will be back to normal with time, so take it easy and rest.” Their kind words lifted the weight off my shoulders and eased my postpartum anxiety, and I was able to return to work.

I’m really glad there are people around you who understand. What do you think is necessary for women to continue making music in this industry for a long time after marrying or becoming a mom?

It’s good to have a place to return to after taking maternity leave. Children are a gift, and there will be times you have to cancel shows. I was grateful there were so many people who understood this and waited for me to come back. This isn’t just limited to the music industry, but if there’s an environment that supports women taking maternity leave, then it will make it more enjoyable for them to look after their kids. And although it may be slow, I think that society is changing. Rather than focusing on the things that mothers and women can’t do, I want to believe that the world is becoming a better place and live my life as I wish.

Many women have careers in classical music, but for example, more men have been awarded at the International Chopin Piano Competition, and the ratio of male and female musicians also differs depending on the instrument. What are your thoughts on the gender imbalance in this industry?

I do sense some remnants of history, like the fact that Western orchestras used to be comprised of only male musicians in the past. A friend of mine, a female musician in an orchestra once told me that it’s hard for women to actively participate in orchestras. I do think that it takes intense conviction. The same is true for office workers. Some might imagine that a woman has to work as hard as a man to advance her career in an administrative position. I think I can make the most of my strength as a woman without compromising my identity.

Have you personally been affected by gender inequality?

I do feel it since I became a mother. Being pregnant was a wonderful experience. Only women can experience nurturing a life inside themselves and giving birth. But I also envy men who can pursue their careers without taking time off when they become fathers.

In addition to motherhood, changes in the stages in women’s lives can sometimes be an obstacle to career advancement.

Women do go through various changes in their lives, like having to raise kids or care for their parents someday. When changes like these happen in the home, more women tend to sacrifice their careers, and it feels like this is linked to gender imbalance in society. Also, women often suffer from physical problems due to hormonal imbalance caused by age. Women have to overcome many obstacles to advance their careers.

Do you have any role models, someone who makes you think, “I want to live my life like this person”?

There aren’t too many (female) classical musicians who continue to be active after having children. So I admire women in any field who flourish in the work they want to do after having kids. But this is my opinion as a married woman who has a child. Whether or not you get married is up to you, and being a mom isn’t everything. I think it’s fine as long as you’re happy.

I think you’re a role model for many people. Do you have any messages for women who might be worried about being able to advance their careers even as changes happen in their lives?

When you can’t find the answer to something even after thinking hard about it, it’s important to summon up your courage and take a step forward. You might gain new perspective, and even if you don’t find it right away, you might be able to arrive at your own answer by taking one step at a time. When I was a teenager, I used to think I had an infinite amount of time, but after becoming a mom, time passes like the wind. So I think it’s better to try the things you want to do now without holding back, and to live your life without regrets.

—This interview by Rio Hirai (SOW SWEET PUBLISHING) first appeared on Billboard Japan

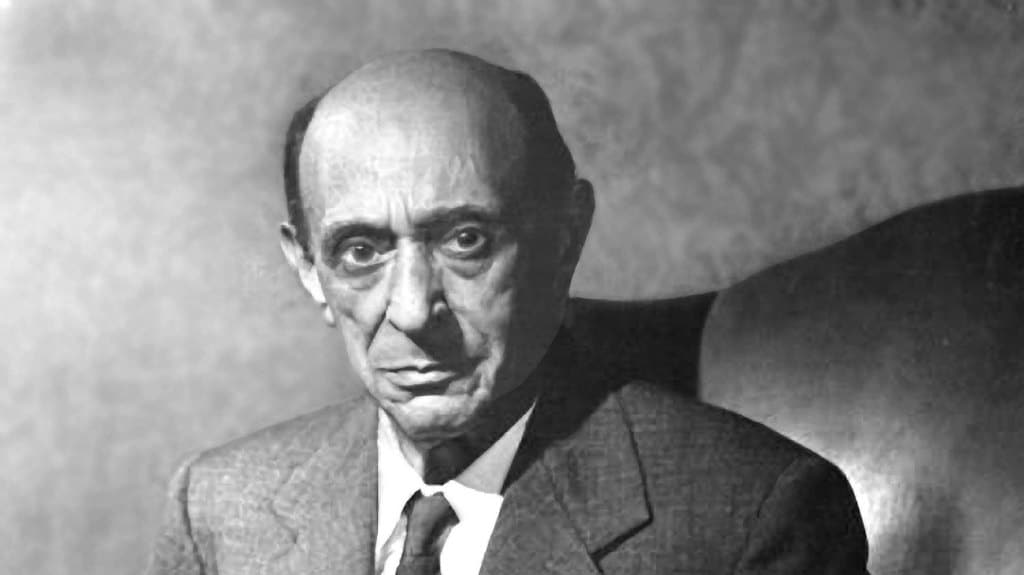

The Pacific Palisades fire destroyed the building housing Belmont Music Publishers, the exclusive publisher of physical works by early 20th century composer Arnold Schoenberg. The fire consumed Belmont’s entire inventory of sales and rental materials, including manuscripts, scores and other printed works, the publisher said.

“For a company that focused exclusively on the works of Schoenberg, this loss represents not just a physical destruction of property but a profound cultural blow,” said a press release written by Schoenberg’s son, Larry, who also lost his home in the fires, according to his nephew E. Randol Schoenberg.

Since the 1970s, Belmont has worked to preserve Schoenberg’s legacy, providing meticulously edited editions of his wide range of transformative compositions, including Verklärte Nacht and Pierrot Lunaire, to musicians and scholars.

Trending on Billboard

Despite the loss of its physical inventory, Belmont Music said it already has plans to rebuild the collection digitally, ensuring the music of Schoenberg — the author of the twelve-tone technique of composition — remains accessible to scholars, performers, and music enthusiasts.

“While we have lost our full inventory of sales and rental materials, we are determined to continue our mission of bringing Schoenberg’s music to the world,” the publisher said. “We hope to rebuild our catalog in a new, digital format that will ensure Schoenberg’s music remains accessible for future generations.”

The Belmont team added, “We are committed to rebuilding and adapting to the changing times. The community’s outpouring of support has been truly heartening, and we know that, with your help, we can ensure that Schoenberg’s legacy lives on in a way that is as dynamic and enduring as his music.”

Born in Vienna in 1874, the self-taught Schoenberg initially drew inspiration from German Romantic composers like Brahms but is most renowned for developing the twelve-tone technique, or serialism, which dispatched traditional tonality and treated all 12 notes of the chromatic scale equally.

As a teacher, Schoenberg mentored influential composers such as Alban Berg and Anton Webern, further cementing his legacy. Fleeing the Nazi regime in 1933, he emigrated to the United States, where he continued composing and teaching in Los Angeles until his death in 1951.

Several wildfires have broken out in Southern California since the beginning of the year, with the largest being in Pacific Palisades along the coast. The major fires have scorched more than 63 square miles, destroyed thousands of homes and killed at least 24 people. Here is a list of organizations providing relief for those impacted by the devastation, from families to first responders.

When he was about 12, Giorgi Gigashvili discovered the Argentine pianist Martha Argerich. A young pianist himself, Gigashvili had recently realized he wanted classical music “to be a part of my life,” and when he came across a YouTube video of Argerich performing Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3, “I fell in love with both the piece and Martha Argerich,” he says.

Argerich became an idol for the aspiring Georgian musician — and, just a few years later, they crossed paths under auspicious circumstances. In 2019, the then-18-year-old Gigashvili won a piano competition in Spain, and he got to meet the head of the jury: Argerich. “That was the moment I truly believed that what I was doing was the right choice,” he says.

Such is the life of one of the global classical music community’s most lauded emerging talents. Now 24, Gigashvili has already amassed a long list of achievements: performing to a sold-out Carnegie Hall in New York, being among the 2023 winners of the world-famous Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition in Israel, earning the distinction of resident artist at the 2024 Beethovenfest in Germany and much more.

Trending on Billboard

But notably, Gigashvili hasn’t limited himself to the genre where he first made his name. Instead, he’s incorporated pop, electronic and experimental music, because he believes that each musical genre has a unique charm — and that none of them should be underestimated.

Ninutsa Kakabadze

Gigashvili’s eclectic taste dates back to his childhood. Long before he was playing to sold-out concert halls and amassing accolades, Gigashvili’s mother and aunt nurtured his love of classical music. “Classical music was always playing in our home, on vinyl or the radio,” he recalls. “The sound of this genre and the works of great composers became part of my memory. We had an old piano at home, and since childhood, I was drawn to touch its keys. I loved its sound.” At age 6, he started taking lessons. “For many children, learning classical music can feel like a stressful process,” he says, “but for me, it was a source of great joy.”

But, concurrently, he was developing an interest in other types of music — and the 2006 musical film Dreamgirls was a major catalyst. An older friend gave him a copy of the film, which he says he watched “several times a day.”

“The music in it was very different from classical music, but it made a huge impression on me,” he says. “This is where the period begins when my love for music and my interest in it were no longer defined by genre. The idea that classical music is isolated and its love excludes the love for other genres is a snobbish approach and has nothing to do with understanding the phenomenon of music. I think it’s wrong to believe that there is no serious genre other than classical music. I don’t divide music into serious and nonserious genres. Every genre, for me, is serious and unique.”

Ninutsa Kakabadze

In turn, despite his recognition in the classical world, Gigashvili has ventured into other genres. He’s drawn on pop, electronic and other modern styles in his repeated collaborations with the young Georgian artist Nini Nutsubidze, which have included modern interpretations of Georgian retro songs — nostalgic for older generations and an engaging way to introduce younger audiences to their culture’s musical heritage. Listeners of all ages have gravitated to the recordings.

At Beethovenfest, Gigashvili performed with Nutsubidze, where they delivered a unique amalgam of classical, folk, electronic, pop, hip-hop and Georgian retro music. “The fact that I, as a classical music performer and pianist, am involved in creative, modern experimental projects makes it even more interesting to Western audiences,” he says. “The global audience today is more curious and interested in experimental approaches.”

Gigashvili says that the creative process differs with each genre — but that these differences are what make his work interesting and diverse. “When you play classical music, the opportunities for interpretation are more limited,” he says, explaining that because classical performers “can’t subtract or add notes,” the genre relies on more subtle differences in aspects like technique and emotion. “I enjoy this limitation because it makes me think more about what I can break and where I can push boundaries. When it comes to performing contemporary music and I am at the keyboard, I am completely free. There’s no need to add my personal signature to specific pieces because I am already the author. These two experiences together create Giorgi Gigashvili.”

Ninutsa Kakabadze

Meanwhile, as Gigashvili’s platform has grown, he has used it to advance causes beyond music. Gigashvili is one of those artists who stands out for his active civic position. With Georgia’s relationship with the European Union at a crossroad, Gigashvili has spoken out supporting the country’s European future and protesting injustice.

“When I express an opinion on social issues, first and foremost, I am a citizen, not an artist,” he says. “This is my primary status. Even on the day I stop performing, I will still speak up and I will still express my position. Today, when Georgia’s European future is at risk, I believe it is every citizen’s duty to clearly express their civic position. This is especially their responsibility if they have a large audience and the right platform. If someone doesn’t have a correct civic position, for me, their art, including music, loses value.”

As Gigashvili anticipates a busy 2025 — he embarks on a tour of America, Asia and Europe in January, and he’ll soon begin recording his second album, which will feature Prokofiev’s Piano Sonatas Nos. 6, 7 and 8 — it is music’s utility as an inspirational tool that continues to motivate him.

“Once, after a concert, an audience member came up to me and said, ‘It seemed like I had forgotten I had emotions, but today, this music made me remember that I am human,’ ” he recalls. “I will never forget this comment. If a performance can make you cry, laugh, feel sad, make you happy or even angry, it means it is real. For me, that is the purpose of music.”

On a balmy recent August evening, Gustavo Dudamel strode onto the stage of the Hollywood Bowl wearing a huge golden gauntlet on his left hand.

He wouldn’t get to use it. Dudamel is dramatic, but he’s no comic book villain; he’s the music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and he was there to conduct the orchestra for the world premiere of Marvel Studios’ Infinity Saga Concert Experience. So instead of wielding the power of assorted Infinity Stones to change the world, Dudamel accepted the “vibranium baton” presented to him by Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige (a reference to the fictional metal of the Marvel universe) and performed some magic of his own, conducting two-plus hours of raucous music from 25 different Marvel movies, backed by gigantic video screens with 3D projections, dancers, fireworks and thousands of screaming fans.

The whole thing looked more like a rock show than a symphony concert. Then again, Dudamel is the closest thing to a rock star the classical music world has.

After nearly two decades in Los Angeles, Dudamel hobnobs with the likes of Chris Martin and John Williams, is close friends with Frank Gehry (who designed the stunning Walt Disney Concert Hall, the L.A. Phil’s home that opened a little over 20 years ago) and counts Billie Eilish, Gwen Stefani, Ricky Martin and Carlos Vives among the dozens of pop world luminaries who’ve guested under his (non-vibranium) baton. He has won five Grammy Awards (including, this year, best orchestral performance for the L.A. Phil’s recording of composer Thomas Adès’ Dante) and placed nine albums at No. 1 on Billboard’s Traditional Classical Albums chart. His life is the subject of the documentary Viva Maestro! And, though never officially confirmed, he was clearly the inspiration behind the character of the free-thinking, mercurial Latin maestro played by Gael García Bernal in the Amazon Prime series Mozart in the Jungle, in which he had a small role as a stage manager.

Trending on Billboard

In the span of just two weeks from the end of August to mid-September, Dudamel conducted Strauss with the Vienna Philharmonic in Salzburg, Austria, and then flew to Los Angeles where, including the two Marvel shows, he led the L.A. Phil in nine concerts, conducting Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony and Beethoven’s Ninth; dances by living Puerto Rican composer Roberto Sierra; Saint-Saëns’ Carnival of the Animals and scenes from Bizet’s Carmen; plus two evenings of contemporary Latin music with Mexican pop/folk singer Natalia Lafourcade. It’s a staggering musical offering. All told, more than 100,000 people attended Dudamel’s nine summer concerts at the Hollywood Bowl with the L.A. Phil, which he will again conduct on Oct. 8 at the opening night of Carnegie Hall’s 2024-25 season in New York.

“He is unique in the classical music world because not only does he lead the orchestra and elevate the work of the L.A. Phil in terms of excellence, but he also connects the orchestra with different kinds of music, collaborating with artists [in other genres] with which we wouldn’t typically perform,” L.A. Phil president/CEO Kim Noltemy says. “The result is he brings orchestra music to so many different people. That is one unbelievably unique piece that makes Gustavo special.”

Joe Pugliese

For Dudamel, it’s part of a deep-rooted belief that music as an art, with purpose, supersedes specific forms and genres. “As an orchestral musician, you value the work of these pop artists, and likewise, pop acts have the opportunity to see that the academicism of the other side isn’t overwhelming, but rather, it’s the same thing in a different style,” he says. “Yes, there’s a fascinating technical complexity [to classical music]. But in the end, what matters is what you feel and what people perceive. We have to erase people’s fears regarding classical music. It may be intellectual in execution, but music’s power is spiritual.”

Not since Leonard Bernstein has a conductor done as much as Dudamel to make classical music accessible — or so thoroughly captured the public imagination. The two maestros share a not just persuasive but borderline evangelical approach to relentlessly promoting music as a “fundamental human right,” not just by broadening what qualifies as “classical” repertoire but also broadening the concept of the orchestra itself. Bernstein’s televised Young People’s Concerts were central to his efforts to expand classical music’s audience; Dudamel has worked to create youth orchestras worldwide. And then, of course, there’s the hair: Bernstein’s silky pompadour flung about wildly as he conducted, and while Dudamel’s signature curly brown mop is perhaps a little less springy than when he made his U.S. conducting debut with the L.A. Phil in 2005 and is now peppered with gray, it still pops and sways with the music.

It’s a visible reminder of the personal stamp he continues to leave in a world of relatively staid personalities, and undoubtedly a factor in his broad recognizability. Dudamel is one of the few faces in classical music known far beyond the space, no doubt one of many reasons the L.A. Phil will miss him when his last season as music and artistic director ends and he officially takes over the New York Philharmonic in its 2026-27 season as music and artistic director.

When he does, Dudamel will become the first Latino to helm the oldest symphony orchestra in the United States, joining a pantheon of giants that includes Arturo Toscanini, Gustav Mahler and Bernstein himself. Expectations for his arrival are so heightened, says N.Y. Phil executive advisor and interim CEO Deborah Borda, that even though Dudamel will not formally join for another season, “we saw a record surge in subscription sales, as patrons are concerned they won’t be able to secure tickets once he starts.”

For Dudamel, being the first Latino to lead the N.Y. Phil long term is a matter of “immense pride. But I feel it doesn’t have to do with a race or a culture,” he says. Historically, he notes, the great symphony orchestras in the United States and beyond have been led mostly by European men who not only represented the music they performed, but also the European migration to this country and Latin America.

Dudamel’s story is completely different. The real triumph “is about where I come from,” he says. “I don’t come from a traditional music conservatory. I come from El Sistema de Orquestas, a program where you grow up playing music with your friends.”

It’s the morning after he has conducted Carnival of the Animals and Carmen, and Dudamel has joined me for coffee in an empty Hollywood Bowl meeting room. He has traded the formal white dinner jacket of the Marvel show for offstage casual — track pants, short-sleeved T-shirt and sneakers — and his trademark mix of impish humor (accentuated by his still-boyish dimples) and deep thoughtfulness. Born and raised in Venezuela, Dudamel learned English as an adult, and though it’s grammatically perfect — albeit with a clipped, precise accent — he prefers his native Spanish, which he speaks very quickly (as most Venezuelans do) and with the erudite lingo of an intellectual, often citing the likes of Spanish writer Miguel de Unamuno or Mexican writer Octavio Paz.

Today, we’re talking not just about his new appointment and the legacy he’ll leave behind in L.A. as he begins to build another in New York, but also the legacy he grew up with — one that still defines him.

At 43, Dudamel is almost as old as El Sistema Nacional de Orquestas y Coros Juveniles e Infantiles de Venezuela (The National System of Venezuelan Youth and Children’s Choruses and Orchestras). Known simply as El Sistema, it was founded in 1975 by musician-economist José Antonio Abreu, who held several government appointments and built El Sistema as part of the government structure, guaranteeing its existence and funding regardless of who was in power.

El Sistema was created more than 20 years before the Hugo Chávez regime, built on the premise that music education should be free and accessible to all children, everywhere in the country. For Abreu, who died in 2018, the power of music was transformative, spiritual and lasting, particularly in a developing country rife with poverty. What started with a first rehearsal attended by 11 children eventually grew to 443 schools (each called a “nucleus” in Sistema terminology) and 1,700 satellite centers that teach over 1 million children in Venezuela’s 24 states, according to El Sistema’s official webpage.

Abreu’s philosophy — famously, he said that “a child who plays an instrument with a teacher is no longer poor; he is a child on the rise” — is one Dudamel not only espouses but assumes as his identity. He’s still the music director of the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela and will tour Europe with it next year for El Sistema’s 50th anniversary. (The tour stops are connected to cities with which Dudamel has a personal history.) He has no plans to change his commitment to it. “I would give my life for the orchestra,” he states bluntly. “It gave me everything I’m living now, and that’s why I share it as much as I can.”

Gustavo Dudamel photographed September 3, 2024 at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles.

Joe Pugliese

But in the last few years, throughout Venezuela’s many political government crises and now, after the contested July reelection of President Nicolás Maduro — who has been in power since 2013 and whose latest reelection has been widely disclaimed both domestically and internationally as rigged — Dudamel has sometimes been criticized by other Venezuelans abroad for not speaking out more against the government.

Some critics have suggested that Maduro has used Venezuela’s youth orchestra to his political advantage. Renowned Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Montero has long called it a propaganda tool; when Dudamel conducted the ensemble at Carnegie Hall days after Maduro’s reelection, Human Rights Foundation parked a truck outside the venue displaying the message “Maduro Stole The Election” and asking Dudamel, “How long will you continue to serve as Maduro’s puppet and henchman?” The organization explained on social media that it wanted “to remind the world of Maduro’s fraud and to call out Dudamel for engaging in shameless propaganda and providing cover for the Venezuelan dictator.”

But, Dudamel points out, he has not been silent. He has written New York Times and Los Angeles Times op-eds calling for an end to repression in Venezuela and speaking against the government’s plans to rewrite the nation’s constitution. In 2017, after Venezuelan government forces killed a young violinist during a protest, Dudamel published an open letter, writing, “Nothing justifies bloodshed. We must stop ignoring the just cry of the people suffocated by an intolerable crisis. I urgently call on the President of the Republic and the national government to rectify and listen to the voice of the Venezuelan people.”

“I am one voice,” he says today. “People think if I speak out everything is going to change, but that’s not the case. There needs to be radical change, and that will take a lot of time.

“We live in a world of immediacy, where there’s always pressure to say something,” he adds when I ask why he hasn’t spoken out more in the wake of July’s contested election. “When do people actually reflect before speaking? You have to consider the entire situation. El Sistema de Orquestas represents all Venezuela, not just a part of it… El Sistema is focused on the neediest communities. That’s the truth. Isn’t that a way to change the country, far more than shouting? So you have to be prudent because you’re part of that. I’m not an individual speaking as an individual because that’s not how I grew up. I grew up in an orchestra.”

Joe Pugliese

This was Dudamel’s mindset during his own first El Sistema experience. He started music lessons at a school in his native Barquisimeto, a quaint city of under 1 million people in northwestern Venezuela. This was the mid-’80s, still years before Chávez took power, but a decade into the existence of El Sistema, which by then was thriving.

“I was only 5 years old, but I remember it perfectly,” Dudamel recalls. “It was the home of Doña Doralisa de Medina. It was a tiny colonial house where Maestro Abreu studied as a child. Doralisa was no longer alive, but El Sistema was there. The house had a red gate with musical notes. I walked in down a passageway and then to a patio, and I heard Chopin on the piano, a trumpet, violins. I fell in love with that cacophony.”

El Sistema didn’t pluck Dudamel out of abject poverty. His father is a working salsa trombonist; his mother, a voice teacher. His uncle, a doctor, was also a gifted cuatro player who taught Dudamel how to play popular Venezuelan music: waltzes, tangos, boleros — what Dudamel calls his very essence.

Perhaps because music flowed through his family, Dudamel’s own studies were encouraged but never imposed. He started conducting by accident, when his youth orchestra’s conductor arrived late for rehearsal and Dudamel took the podium, almost as if it was a game.

While no one ever told him he would make it big, his talent would have been impossible to miss. Abreu took an early interest in him, becoming a mentor and moral compass. He’s still very much alive in Dudamel’s head — he constantly begins sentences with “El Maestro Abreu…” — as are his teachings: to think long term, to learn from mistakes, to see music as a social instrument. It was Abreu, after all, who urged Dudamel, then in his early 20s, to enter Germany’s prestigious Mahler Competition, for conducting works by the vaunted composer, in 2004. When he won, it changed his life, catapulting him from local star to global wunderkind.

Among the jurors was Esa-Pekka Salonen, the Finnish composer and current San Francisco Symphony music director who was, at the time, music director of the L.A. Phil. “I was deeply impressed by the talent of this guy, but also, I felt he was such a good guy,” Salonen recalls. “I told him I wanted to invite him to L.A.” As he got to know Dudamel, he continues, “I became so convinced about him being my favorite person to take over in L.A. and become my successor, taking [the orchestra] in a different direction but keeping his curiosity and openness.” A mere three years later, Salonen’s wishes came true: the L.A. Phil — where Deborah Borda was then executive director — appointed Dudamel music director, effective with the 2009-10 season.

Dudamel’s personable demeanor and charismatic conducting style immediately enchanted L.A. audiences and the ensemble’s players alike — he is, after all, affectionately known as “The Dude” to both cohorts. But from the jump, his mission went far beyond the podium. “I was very young, and evidently there was a human and artistic connection with the orchestra and the administration,” he says. “But my first order of business was creating El Sistema here. That’s how YOLA began.”

YOLA is Youth Orchestra Los Angeles, the L.A. Phil’s music education program, that Dudamel created in 2007. It currently serves close to 1,700 young musicians across five sites in the city, providing them free instruments, intensive music instruction (up to 18 hours per week), academic support and leadership training. The program has inspired hundreds of versions around the world; in the United States alone, El Sistema USA serves 140 member programs, 6,000 teaching artists and 25,000 students. Dudamel also launched a mentorship program for young conductors in 2009 and now brings four each season to assist the L.A. Phil’s guest conductors.

But education and training are just part of the equation to “create identity and have people see themselves reflected in the [L.A.] Philharmonic,” Dudamel says. “Right or wrong, cultural artistic institutions are seen as elitist for many, especially those who don’t have resources. The adventure was to make of the [L.A.] Philharmonic an institution people could identify with.”

Dudamel began doing this gradually by being more experimental in his programming, adding more pop and jazz guest artists, bringing Hollywood into the mix (he has famously played multiple concerts of John Williams’ music, with Williams in attendance) and opening up the repertoire to new works and unexpected juxtapositions. A ticket buyer who might not want to hear a world-premiere commission might be lured in by Beethoven; one allergic to the idea of Beethoven might reconsider after seeing an orchestra perform with Ricky Martin.

“For me, it wasn’t only about building a good orchestra,” Dudamel says. “That already existed. But now we have one of the top orchestras in the world, respected as much for its technical level as for its proud acceptance of the repertoire and the way they perform it. This wasn’t ‘Oh, Gustavo, come in and do whatever you want.’ It was figuring out how to build it.” Dudamel had the Hollywood Bowl, Disney Hall and the orchestra. “All the elements were there,” he continues. “We just had to get the best out of them. And there’s still a lot to do.”

Gustavo Dudamel photographed September 3, 2024 at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles.

Joe Pugliese

Dudamel conducted the L.A. Phil at the 2011 Latin Grammys and the 2019 Academy Awards. He led the orchestra alongside Billie Eilish and FINNEAS as part of the concert film experience Happier Than Ever: A Love Letter to Los Angeles, released on Disney+. And he performed at the 2016 Super Bowl halftime show with members of YOLA, alongside Coldplay, Beyoncé and Bruno Mars.

“His authentic, warm connection with audiences really changes how people feel when watching a concert. Audiences are so excited to see him, and there’s a buzz around him,” Noltemy says, noting that pandemic era aside, attendance and audience diversity at the L.A. Phil have increased while the average age of concertgoers has decreased. “He’s certainly not the only conductor who has increased attendance and brought diversity, but he did so in L.A., a city that is so spread out. His concerts at Disney Hall tend to be sold out.”

Those results have occurred even as Dudamel has made a huge effort to foster contemporary composition (typically not an old-school orchestra subscriber’s favorite programming), commissioning music from composers around the world. During his tenure at the L.A. Phil, the orchestra has premiered “at least 300 new works” written specifically for the ensemble, he says, including many from Latin America.

“Latin American repertoire has to stop being [perceived as] exotic,” he says. “It’s not about ‘Wow, we’re playing Latin American music!’ No. It’s the fair thing to do. And the only way to include it in the repertoire is playing it but at the level it deserves, making it part of the regular repertoire of any orchestra.” Case in point: Mexican composer Gabriela Ortiz, a Dudamel mentee who was just named Carnegie Hall’s composer-in-residence for the coming season. In July, Platoon released her first full album of orchestral works, Revolución Diamantina (performed by the L.A. Phil and conducted by Dudamel), which is being submitted for Grammy consideration.

Just how much of his approach with the L.A. Phil Dudamel will be able to replicate in New York remains to be seen; as he says, he has yet to formally arrive and experience the orchestra. But in recent months, he has been working with both orchestras to forge a connection between the two.

In April, when Dudamel conducted the N.Y. Phil’s Spring Gala at Lincoln Center’s David Geffen Hall, he featured rapper Common, former New York Yankee and classically trained guitarist Bernie Williams and student musicians from several New York music schools, performing a program that also included classical works by Villa-Lobos and Strauss, as well as a premiere commissioned by the N.Y. Phil and Bravo! Vail Music Festival.

It was the kind of bold, cross-genre programming that Dudamel delights in doing in L.A. and clearly wants to emphasize in New York. “It was something completely new and wonderful. For me, that’s the kind of thing that makes the music transcend beyond the sometimes strict academic and intellectual isolation that classical music represents,” he says. “We can develop a lot in terms of repertoire and go beyond Lincoln Center and connect more with the entire community.”

Gustavo Dudamel photographed September 3, 2024 at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles.

Joe Pugliese

The N.Y. Phil, for example, is known for its massive annual free outdoor concert on the Great Lawn in Central Park, which is always attended by no less than 50,000, and it also performs in all five boroughs during its annual Concerts in the Parks. But the L.A. Phil has the Hollywood Bowl, an outdoor venue that seats 18,000 and is the orchestra’s home for the entire summer. It’s a big difference that Dudamel would like to somehow bridge.

He also joins the N.Y. Phil after the 2022 reopening of Geffen Hall following a $550 million renovation that drastically improved its acoustics. He says the new venue did not factor into his decision to go to New York, “but it was very important, especially for the orchestra. It’s been a plus to elevate the morale. Now the orchestra is in the process of building its sound with the ‘instrument’ [that is the new hall].” Optimism is also high following the Sept. 20 finalization of a new labor contract that ensured 30% raises for the orchestra’s musicians over the next three years, bringing their base salary to $205,000.

Dudamel is also taking the reins of an institution that lately has had its share of highly publicized troubles. After just one year on the job, N.Y. Phil CEO Gary Ginstling stepped down in July amid rising tensions with the orchestra’s board, according to a New York Times report. And the orchestra’s public image has been tarnished after reports earlier this year resurfaced a 2010 sexual misconduct charge made against two of its musicians. Although charges were never filed against the two men, the controversy led to the musicians being put on leave; they then sued the N.Y. Phil for doing so.

As Dudamel is not yet officially the N.Y. Phil’s music director (for the 2025-26 season, he is music director designate), he won’t comment on administrative matters other than to acknowledge that “those are problems that need to be resolved.” And although the administration of the orchestra ultimately is not his purview, “Obviously the morale of the orchestra is my responsibility, and you have to keep that morale high, taking the best decisions and advocating for justice for everyone,” he says. “That’s essential. We’re not isolated from what happens around us.”

Whatever may have occurred before his tenure begins, Dudamel is without a doubt joining an orchestra that respects him as a conductor, whose musicians have a history and rapport with him. “There was an undeniable spontaneous connection between our musicians and Gustavo, so much so that he was literally their only choice to be our next music director,” Borda says. “Selling tickets is important, but we believe this is best accomplished when you have the right artistic leader.”

Dudamel is acutely aware of the expectations now surrounding him. “It’s a challenge, but life without challenge… it’s nothing!” he says with some relish. “But I’m not a savior here. I have nothing to save. What we have to do is build, and that’s not just up to me. We have a great team.” And after all, he’s Dudamel — and by now, he understands it comes with the territory.

“People want you to scream what they scream, but no. To me, change isn’t about screaming but about building things that last, as I learned from Maestro Abreu,” he says. “I sincerely believe artists should be symbols of unity … They must guarantee that cathartic, unifying space we all need — not just here or in Venezuela, but everywhere.”

Joe Pugliese

This fall, for example, Dudamel will lead the L.A. Phil in Mendelssohn’s music from A Midsummer’s Night Dream with his wife, Spanish actress María Valverde, providing narration — music by a German composer, written for the work of a British playwright who derived it from a Nordic story, now narrated in Spanish, conducted by a Venezuelan and performed by an American orchestra. Plus, the evening will feature the premiere of Ortiz’s new cello concerto.

“It’s the kind of thing you don’t even remark upon because it feels natural. But it’s a true reflection of diversity,” Dudamel says. “When you see all these elements come together, you realize, ‘Wow, this is powerful.’ ”

He speaks about this blend of so many seemingly disparate elements as if it’s destiny, or magic. But a moment like that — much like a career such as Dudamel’s — doesn’t occur by happenstance or without purpose.

“One thing about Gustavo I think needs to be said is that for someone who had a lot of success from very early on, he’s remarkable in that he never lost his center,” Salonen says. “He has never lost his ideals. He believes in music as a social cause, and he believes in music and the arts as a very central thing in keeping the fabric of society strong. And despite all the success and fame, he’s still the same guy I met all those years ago.”

This story appears in the Oct. 5, 2024, issue of Billboard.

On a balmy recent August evening, Gustavo Dudamel strode onto the stage of the Hollywood Bowl wearing a huge golden gauntlet on his left hand. He wouldn’t get to use it. Dudamel is dramatic, but he’s no comic book villain; he’s the music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and he was there to conduct […]

A performance years in the making became dazzling reality in August at Burning Man, when DJ-producer Mita Gami played with conductor Meir Briskman and an orchestra assembled especially for the occasion.

The hour-and 15-minute performance happened mid-week at Burning Man 2024 on the festival’s famed Mayan Warrior art car, a new version of which made its debut at the event this year after the original was destroyed in a fire in April 2023.

The Israeli conductor came up with the idea for the performance years ago and brought it to Gami, with the pair performing together since 2022 with an electronic/classical fusion show for which Briskman wrote and conducted the orchestral elements, with Gami producing and performing the electronic components.

Trending on Billboard

For Burning Man, the orchestra was assembled after the pair put a call out to players, with 123 people applying to be in the orchestra and 37 of them ultimately selected to perform. On Instagram, Briskman wrote that the performance came together “after 3 years of work, 1467 phone calls, 4356 emails [and] 5942 WhatsApp messages”

“Our search to find classically trained players that were going to Burning Man began through posting via our instagram stories,” the pair tell Billboard in a joint statement. “The message rapidly spread, and we received an overwhelming number of responses. Despite the limited rehearsal time, we embraced the challenge and turned our dream into a magical reality, delivering a complex performance that flowed effortlessly.”

The performance was managed by Amal Medina, a member of Gami’s management team, a co-talent buyer for Los Angeles-based electronic events company Stranger Than and the talent buyer/events coordinator for Mayan Warrior. Medina helped manage the orchestra and handled logistics such as vetting the musicians, organizing rehearsals in San Francisco and at Burning Man and sourcing equipment and instruments and managing the orchestra. Tal Ohana of Stranger Than helped gather equipment and staging elements for the performance, The Mayan Warrior team worked on onsite and sound and lighting elements.

The performance was well-aligned with the goals of the new edition of Mayan Warrior, with the art car’s founder Pablo Gonzalez Vargas telling Billboard in 2023 that the team was planning to “slowly transition into a more diverse spectrum of musical and cultural performances. The goal over time is to have more live acts with real instruments that can provide new experiences.”

Other performers on Mayan Warrior during Burning Man included Rüfüs du Sol, whose set is also up now.

Watch the Mita Gami & Meir Briskman Orchestra Set exclusively on Billboard.com below:

Venezuelan conductor and violinist Gustavo Dudamel received the 14th Glenn Gould Prize during a ceremony at Carnegie Hall on Aug. 2. Dudamel is music and artistic director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela and is set to become music and artistic director of the New York Philharmonic in 2026.

Previous recipients of the Glenn Gould Prize, called Laureates, include Yo-Yo Ma, Jessye Norman, Leonard Cohen, Lord Yehudi Menuhin, Alanis Obomsawin, Philip Glass, Robert Lepage, and Oscar Peterson.

Dudamel, 43, is the first Laureate who had previously been awarded the Glenn Gould Protégé Prize, having been selected by his mentor and Glenn Gould Prize Laureate Dr. José Antonio Abreu in 2009.

Trending on Billboard

Selected by the Laureate themselves, the Glenn Gould Protégé Prize is awarded to an outstanding young artist demonstrating exceptional promise with a cash award of CDN$25,000. This year, Dudamel selected two young conductors, both also from Venezuela, to share the Protégé Prize – Andrés David Ascanio Abreu and Enluis Montes Olivar.

The Canadian Consul General to New York, the Hon. Tom Clark, and Glenn Gould Foundation executive director Brian Levine, presented the awards onstage at Carnegie Hall during a concert in which Dudamel conducted the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra.

“It is a huge honor to receive this prize,” Dudamel said in accepting his honor. “Years ago, I was a Protégé Prize winner, given to me by my Maestro Abreu. It makes me very proud, especially to be here with all these amazing young people from my country, Venezuela.”

Nominees for The Glenn Gould Prize are submitted through an open, public nomination process and can come from a broad range of artistic fields. An international jury comprised of artists and professionals from diverse disciplines convenes in Toronto, Canada (where Gould was born and where he died) to review the nominees and select the Laureate. The Glenn Gould Prize Laureate is awarded a cash prize of CDN$100,000.

The Glenn Gould Foundation, established in 1983, is a registered Canadian charitable organization dedicated to celebrating excellence in the arts and promoting cultural enrichment globally.

Gould, a Canadian classical pianist, won four Grammys and three Juno Awards. He is best known for Bach: The Goldberg Variations, which he recorded in both 1955 and 1981. The earlier recording was voted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1983. That same year, his digital re-recording won both a Grammy and a Juno for best classical album. Sadly, all of these awards were posthumous: Gould had died in 1982 at age 50. He received a lifetime achievement award from the Recording Academy in 2013.

Cincinnati is going all-in on getting a pop king to the Queen City. Mayor Aftab Pureval and Vice Mayor Jan-Michele Lemon Kearney were joined by leaders from the Cincinnati Opera and a variety of regional partners on Wednesday morning (May 22) at Cincinnati Music Hall to announce a full-court-press effort to persuade Paul McCartney to visit the city this summer for the Opera’s upcoming world stage premiere of Paul McCartney’s Liverpool Oratorio.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

The summer-long “Come Together, Cincy! Get Paul to Music Hall!” effort aims to get Sir Paul to say “yes” to the invitation to celebrate the premiere in July after the former Beatle agreed to allow his first classical piece — a 1991 tribute to his hometown co-written with composer Carl Davis — to be staged in the city.

Trending on Billboard

“This is a special time in Cincinnati, and the world stage premiere of Sir Paul’s Liverpool Oratorio is an incredible example of the excitement building around the Queen City,” Mayor Pureval tells Billboard. “Cincinnati’s vibrant cultural community helps put us on the map, and our reputation as a world-class arts destination brings real eyes and real tourism into our region. Folks from around our community, and around the world, are ready to Come Together and celebrate a truly one-of-a-kind experience here in town.”

The Oratorio will be presented on the opera stage for the first time from July 19-27 at Music Hall. According to a release announcing the effort, McCartney, 81, endorsed the new production in a letter to the Opera, in which he wrote, “I am writing to express my wholehearted support for this project. I believe that the Cincinnati Opera is uniquely positioned to bring this work to life in a new way, and I have no doubt that your production will be an inspiring experience for all who see it.”

At press time it was unclear if McCartney was planning to travel to the city for the debut.

In the meantime, the region will be blanketed with “Get Paul” enticements in an effort to convince the singer to return to Cincy for the first time since a 2016 arena show. The project announced on Wednesday morning will include a barrage of ads this summer featuring the Opera and McCartney on Metro buses, at the CVG international airport, at Reds and FC Cincinnati soccer games, as well as a number of iconic downtown locations. The fanfare will kick off this weekend at the city’s traditional summer kick-off event, Taste of Cincinnati, which typically draws more than half a million visitors to the streets of downtown.

Local residents are also encouraged to record a video tribute to Sir Paul and to post it on their socials using the hashtag #GetPaulToMusicHall, with the release saying that tagged videos amplified by the Opera and “Come Together” partners will be shared with McCartney’s team.

“We’re looking forward to launching the ‘Come Together, Cincy!’ campaign this weekend at Taste of Cincinnati, courtesy of our partners at the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber,” said Cincinnati Opera CEO Chris Milligan in a statement. “Attendees can stop by the Opera booth and record their video tribute to Sir Paul by sharing a favorite memory or singing a snippet of a McCartney tune… Let’s get Paul to Music Hall!”

The Liverpool Oratorio live album was released in 1991 as part of a commemoration of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra’s 150th anniversary. The eight-movement piece that follows a character named Shanty as it roughly sketches out McCartney’s life story had its American premiere in Nov. 1991 at Carnegie Hall.

Check out the full calendar of “Get Paul to Music Hall!’ events here.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio