Business News

Page: 18

For years, to make the Canvas Power 15, Walrus Audio has spent $95.32 per unit on parts. So the rainbow-stamped power supply device for multiple guitar pedals has rarely cost customers more than $270, a price consistency that has helped the 14-year-old Oklahoma City company earn $10 million in annual sales and employ 31 guitar players. “We were cruising, and stuff was selling, and we’re like, ‘Man, we’re having a fun year,’” owner Colt Westbrook says.

But a surge protector that resembles a small, black brick is a key part of every Canvas Power 15 package and can be made in only one country: China. Last month, when the Trump Administration raised tariffs for Chinese imports from 84 percent to 145 percent, the cost to make the Power 15 soared to $139.54. That gave Westbrook a choice: Raise Walrus’ prices, potentially alienating customers, or slash expenses. “We’d have to lose some people,” says Westbrook, whose customers include Maroon 5, the Roots, Haim and Bon Jovi. “We’d have to cut some products, because they wouldn’t be financially viable anymore. Which would be sad.”

Given the unpredictable nature of recent U.S. tariffs on China, and, to a lesser extent, other countries, Walrus is one of many music-gear manufacturers freaking out about the sudden instability of its long-steady industry. Although Trump announced a trade deal with China last week, lowering the U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports to 30 percent, Westbrook was not reassured. “Everybody’s just, ‘We’re holding onto our cash because we don’t know what’s going to happen,’” he says.

Trending on Billboard

Small music-gear companies fear the worst. In testimony Wednesday (May 14) before the U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Julie Robbins, owner/CEO of EarthQuaker Devices, a 35-employee Akron, Ohio, guitar-effect pedal manufacturer, declared the tariffs are “putting us at risk of bankruptcy,” demanded they be “reversed immediately” and dismissed “offensive” suggestions that she borrow money to cover fees “abruptly imposed on me by the government with no notice and no consideration.”

Although many music instruments are manufactured in the U.S., as well as relatively low-tariffed countries like Canada, Mexico and Indonesia, John Mlynczak, CEO/president of the National Association of Music Merchandisers (NAMM), recently told Billboard: “China is the largest manufacturing hub for products worldwide.” Gear-makers big and small say circuit boards, capacitors, resistors, transistors, fret wire, tubes and, as Walrus discovered, surge protectors, are made outside the U.S. — and many come from China alone.

“Nearly all musical products imported into the world’s largest market for [these] products are affected,” Mlynczak says by email. “This could have a devastating effect not only for the companies in our industry, but also for music-makers who buy these products.”

Trump recently declared U.S small businesses would not require government relief: “They’re going to make so much money — if you build your product here,” he said. But Josh Scott, owner, creator and president of Kansas City-based JHS Pedals, which employs 40 people and releases 100,000 products annually, argues Trump’s prediction can’t come true in his industry, which relies on parts that haven’t been made in the U.S. for years, if ever. “It’s like telling someone in Detroit to make diamonds out of the ground,” he says. “It’s physically not a thing.”

“It’s not just going to affect gear prices. It’s going to put a lot of these people out of business,” adds Rhett Shull, whose YouTube guitar-tips channel has 728,000 followers. “We’re heading for a massive nationwide shortage of goods in about a month. Even if Trump said, ‘Oh, nevermind, tariffs off, we’re all good,’ the damage is already going to be done.”

Due to the tariffs — and the uncertainty surrounding the tariffs — music-business products from T-shirts and other merch to vinyl records are bracing for higher manufacturing prices. U.S. companies that specialize in music gear are already seeing the impact: Philippe Herndon, founder/chief product designer for Caroline Guitar Co., recently posted on Threads that his company was “startled” to receive a March tariff bill that was “twice as much as we were expecting”; John Snyder, owner of Electronic Audio Experiments, adds in an interview that the cost of metal enclosures used for a new pedal “basically tripled overnight,” forcing his $1 million-in-annual-sales company to discontinue the product. “You don’t want to pass that cost onto the customers,” he says. “At some point, you have to take the ‘L’ and move on, and focus on stuff where the margins are better.”

The tariffs haven’t fully kicked in for the music-gear business, in part because of Trump administration uncertainty: In addition to the fluctuating tariff rates, particularly on China, Trump has granted, without much explanation, exemptions for certain industries, like smartphones, laptops and other electronics. NAMM has lobbied U.S. senators and the Commerce Department for an exemption on the types of lumber, known as tonewoods, that are used in guitars.

Another reason consumers may not have noticed a widespread increase in guitar-gear costs: Like many aggressive U.S. businesses, some music-equipment companies began preparing when Trump won the 2024 election. Electronic Audio Experiments, according to Snyder, spent last December and January working with a longtime supplier to buy as much inventory as possible so the company could maintain prices through the end of 2025. “Our circuit-board assembly house is located in North Carolina. We loaded them up with as much raw material as we could stand and just tried to coast from there,” Snyder says. “It was a very anxious time. Nobody knew exactly what was happening. We just knew it was going to be bad.”

For now, some music-gear manufacturers detect a shift among consumers to the used market. On Reverb, which sells new and used gear, April prices dropped by about 1 percent compared to the same time in 2024. “There have been a few manufacturers who have raised prices in the last few weeks on synthesizers and pedals,” says Cyril Nigg, Reverb’s senior analytics director. “A lot of the other manufacturers are trying to hold prices where they are for now. The retailers who are selling those products on Reverb are trying to keep the prices stable.”

Used gear prices are typically about 50 percent to 80 percent of the new price, according to Herndon, whose company earns less than $500,000 in annual sales. “The used market is indexed to the price of new goods,” he says. “Somebody goes, ‘I want to buy a Stratocaster, and everything has gotten more expensive — screw this, I’m going to buy it used.’ Well, the tariffs have raised the price of the new goods, and now the used goods are going to come up.”

Elizabeth Dilts Marshall contributed to this report.

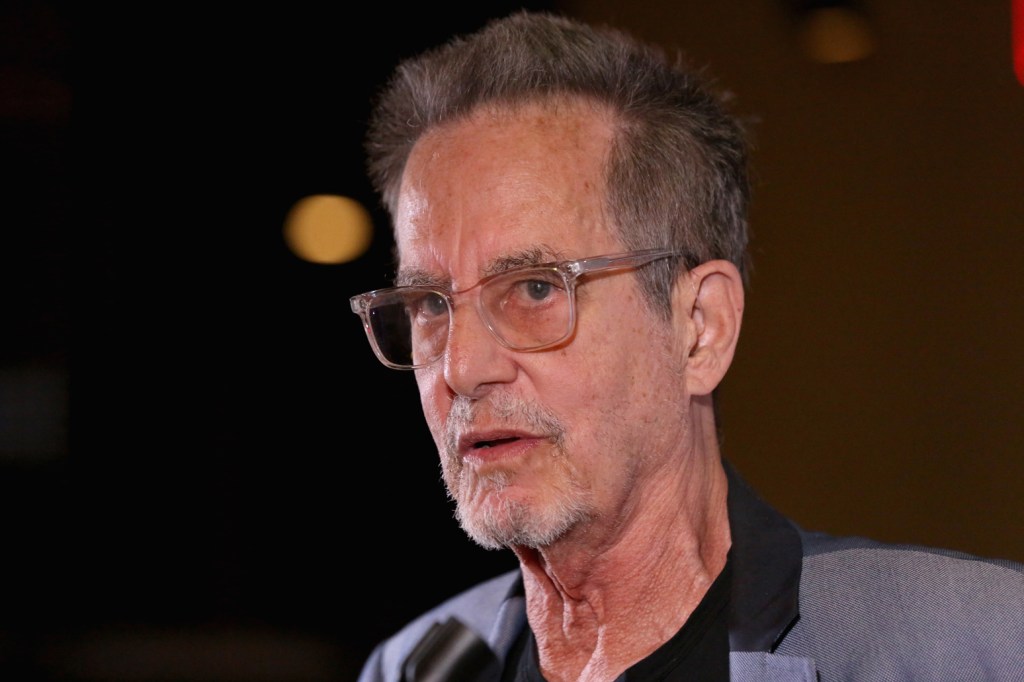

Brian Avnet, who began his long career as a road manager for Bette Midler and later managed such top acts as The Manhattan Transfer, David Foster, Josh Groban and Eric Benét, died in Los Angeles on Wednesday (May 14), after living with Parkinson’s disease for many years. He was 82.

Avnet was inducted into the Personal Managers Hall of Fame in 2017, in the same class as Sid Bernstein, Eileen DeNobile, Eric Gardner, Richard Linke, Lois Miller, Eliot Roberts, Dolores Robinson, Arthur Shafman, David Sonenberg, Rick Siegel and Jerry Weintraub.

Trending on Billboard

On hearing of his death, Linda Moran, CEO of the Songwriters Hall of Fame told Billboard, “Brian was loved by everyone who knew him. [He] was a familiar face at Atlantic and WMG over the years as most of his artists were signed there.”

Based in Los Angeles, Avnet was a personal manager for nearly 40 years. In addition to those named above, his clients also included Johnny Mandel, Herb Alpert and Lani Hall Alpert, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, Joshua Ledet, Cyndi Lauper, Take 6 and Jean-Luc Ponty.

Avnet worked with Midler in the early days, starting when she was playing bathhouses in New York before bursting to stardom in the early 1970s. Avnet served as general manager for Midler’s 19-show run at the Palace Theatre in New York in December 1973 for which she won a special Tony Award “for adding lustre to the Broadway season.”

He managed The Manhattan Transfer for 19 years starting in the late 1970s, including when they landed their biggest hit, “Boy From New York City.” That song made the top 10 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1981 and won a Grammy for best pop vocal performance by a duo or group with vocal.

Avnet was a personal manager for Foster, a 16-time Grammy-winner. In that capacity, he worked on recording projects by such stars as Whitney Houston, Celine Dion, Toni Braxton, Natalie Cole, Diana Krall, Faith Hill, Brandy, En Vogue, Olivia Newton-John, The Bee Gees, Michael Bolton, All 4 One, Julio Iglesias, En Vogue and Smokey Robinson.

He played a key role in discovering Groban, whom he later managed. He found the singer through Seth Riggs, the top vocal coach, and brought him to Foster.

When Foster signed a deal with Warner Bros. in 1995, it enabled him to start 143 Records. Foster hired Avnet to run the label, with a roster that included Groban, Michael Bublé, The Corrs and Beth Hart. Bublé’s first three No. 1 albums on the Billboard 200 – Call Me Irresponsible, Crazy Love and Christmas – were released on the 143 imprint, as were Groban’s first two No. 1 albums on that chart – Closer and Noel.

The Corrs, a sibling pop band from Ireland, had three Billboard 200 albums while on the label; Hart, a Los Angeles-based singer/songwriter, had one.

Foster later sold the label back to Warner. On Sept. 20, 2001, Warner Music Group announced it was shutting down the label.

Avnet’s widow Marcia Avnet told Billboard that her husband grew up in Baltimore and started his career in theater. “He was the youngest theater manager,” she said. “Actually, he used to manage the theater in-the-round in Maryland and then he was roommates with Dustin Hoffman in New York. And Jon Voight. They were all roommates when those guys were doing summer stock. Brian was in management, he ran the ticket booth, did lots of different jobs.”

Early in his career, he served as producer of A Streetcar Named Desire starring Voight at the Studio Arena Theatre in Buffalo, N.Y.

He moved to Los Angeles in the early 1974 to work with Lou Adler on the production of the Rocky Horror Show, which played at The Roxy for nine months. It was turned into a film, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, the following year. The film has long been a cult favorite. Avnet also produced the rock opera Tommy in Los Angeles; and served as manager for the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar at the Universal Amphitheater in Los Angeles.

He also managed the first season of the Universal Amphitheater.

Avnet worked with producer Robert Stigwood on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band on the Road, an off-Broadway production which opened at the Beacon Theatre in New York in November 1974 and ran for two months. The show was loosely adapted into an ill-fated 1978 film version starring The Bee Gees and Peter Frampton.

Avnet frequently participated in events like Grammy Career Day. At a 2009 workshop, he served alongside such industry professionals as John Burk, Tom Sturges, Tina Davis, Rickey Minor, Harvey Mason Jr., Mike Knobloch and Javier Willis.

The Avnets were together for 36 years; married for 26 of those years.

“It was a really long career, and he was beloved,” said Marcia Avnet. “He never signed a contract with anybody. His word was his bond. And that’s really rare.”

Additional reporting by Melinda Newman.

With more than 2,000 attendees converging on Atlanta for the annual Music Biz conference at the Renaissance Atlanta Waverly Hotel and Convention Center Galleria, Music Business Association president Portia Sabin opened day 2 by reminding everyone of the “guiding belief” behind the Music Business Association and its conference — while revealing the conference will return to Atlanta next year.

“We’re all better together,” Sabin proclaimed. “We know we can achieve success and overcome any challenge in our way when we come to the table with open minds, foster collaboration, and develop solutions that truly support one another.”

Sabin pointed out that the music industry has become truly global in the past several years and, corresponding to that, international music companies now comprise one-fifth of Music Biz’s membership. What’s more, she said 15% of the attendees at this year’s conference (which runs from May 12-15) are from outside the U.S: “That’s 250 individuals, representing 168 companies and over 30 countries, ranging from Vietnam and Australia, to Japan and Egypt,” she said.

Trending on Billboard

In order to better represent its membership and the global music industry, “we’ve embraced this shift by hosting our virtual Passport series — free webinars that dissect issues in music markets across the globe — as well as expanding our traveling Roadshow series with our first international event in Toronto this past March,” Sabin added.

Finally, Sabin pointed out that in preparing to hold the conference in Atlanta over the last year, Music Biz hosted a number of mixers and meetups to “build relationships with Atlanta’s vibrant music business community. Most recently, we partnered with the Mayor’s Office of Film, Entertainment and Nightlife for an event at City Hall, to connect local & global music professionals and preview some of the programming we offer at our conference.”

After holding the convention for the last 10 years in Nashville, the Music Biz conference is going on the road again, just like its antecedent organization, the National Assn. of Recording Merchandisers, did for decades by moving the annual convention to various cities. However, Sabin revealed that Atlanta will host the convention again next year, too, while thanking the city and the hotel for supporting it.

“Thank you to the team here at the Renaissance for making this year’s event possible, and to the city of Atlanta for being such gracious hosts ever since we announced plans to bring our conference here in 2025 and 2026,” Sabin said at the beginning of her remarks to attendees.

At the Music Biz 2025 conference in Atlanta, the “Let’s Get Physical” segment opened with a panel featuring Luminate’s director of partnerships, Chris Muratore, who shared the latest industry insights around the continued success of Record Store Day.

One of Muratore’s slides pointed out that in the last 10 years, there have only been a dozen weeks in which album sales reached the 1 million unit mark, and Record Store Day was responsible for five of those weeks, with most of the other million-selling weeks coming during the year-end holiday season.

Staying with the panel’s theme of updating the industry on “Indie Retail Sales Data,” Muratore explained how Luminate — which shares a parent company with Billboard, Penske Media — has evolved its approach since partnering with StreetPulse to gather data from independent record shops.

Trending on Billboard

Muratore — who was joined by Coalition of Independent Music Stores executive director Andrea Paschal and StreetPulse CEO John Weston on the panel — began with a brief history lesson, explaining how Luminate’s predecessor, SoundScan, first began tracking indie retail data back when physical music was the only game in town. At the time, around 300 independent stores reported sales. However, the weighting system used to extrapolate sales for the entire indie sector hadn’t been updated since it was first implemented in 1991.

When Luminate began its collaboration with StreetPulse in 2024, it was only after it had made the controversial decision to end weighting for indie stores at the end of 2023, resulting in widespread industry resistance.

By June 2024, Luminate struck a deal to collaborate with StreetPulse on collecting indie retail sales data and assembled a dedicated data team to develop a new, more flexible and efficient weighting model to replace the outdated system. As part of the partnership, Luminate initially gathered sales reports from 200 indie stores, with the number growing to around 250 stores by the end of 2024, according to Muratore.

For her part, Paschal acknowledged that Music Biz president Portia Sabin “was very involved in bringing us all together.”

Muratore noted that, through its partnership with StreetPulse, Luminate continues to expand its network of reporting stores, now surpassing 400 locations contributing sales data. “We think we have identified another 100-plus stores to bring on by the end of the year, so we will have over 500 stores reporting sales,” he said.

In order to get to 500 stores, Weston thanked labels and distributors for pointing out retailers that should be added. Then, speaking to store owners, he pointed out that one of the challenges is that every store owner runs their business “a little different.” “There is a reason you are called independent because you are all different,” he noted. “So if you are not reporting to us and want to, we need to know what kind of POS system you have.”

While Luminate may reach 500 reporting stores — roughly one-third of the estimated 1,500 independent U.S. shops selling new physical music — by year’s end, that one-third likely represents about two-thirds of total physical sales volume. Conversely, the remaining two-thirds of stores that aren’t yet reporting likely account for just one-third of the volume. “That’s because we know who the tier 1, tier 2 and tier 3 stores are,” Muratore explained.

Also, as Luminate and StreetPulse add stores, the new weighting system is flexible enough to accommodate the new ones coming on without distorting the sales picture.

Using the new weighting system, Luminate apparently backfilled the weighted numbers back to the beginning of last year because Muratore reported that in 2024, while physical sales were 77.8 million, the largest segment was indie retail, which collectively sold 23 million album copies of vinyl and CDs, representing 36% of physical sales.

Breaking it down, Muratore noted that of the 44.4 million vinyl albums tracked by Luminate in 2024, independent retailers accounted for 17.3 million — roughly 36%. And indie retail continues to gain ground, particularly in vinyl sales: In just the first four months of 2025, indie stores were responsible for 5.7 million of the 13.1 million vinyl units sold, representing 44% of total sales, he said.

As for CD sales, last year indie stores collectively accounted for 5.4 million of total U.S. sales of 32.9 million CD copies, or 17% of CD sales. So far this year, indie stores account for 1.8 million units of the 8 million CD sales recorded so far — or 22% of CD sales.

Focusing on Record Store Day, Muratore emphasized the importance of recognizing who’s buying physical music today. Unlike the early days of the vinyl revival, he noted, it’s no longer just older people driving sales of physical music — and Record Store Day clearly reflects that shift.

Muratore reported that the top three Record Store Day 2025 titles were Taylor Swift’s “Fortnight” single featuring Post Malone, which led with 59,000 copies sold; Malone’s Tribute to Nirvana with 12,000 copies; and Gracie Abrams’ Live From Radio City Music Hall, which moved 11,000 units.

Muratore further emphasized the shift toward a younger demographic in physical music buying, noting that a recent Luminate consumer survey found that 25% of vinyl purchasers are under the age of 25. He went on to urge labels and music distributors to make sure “they put the right product out for who the consumer is for physical,” adding that the younger physical music buyers wanted Swift and the Wicked soundtrack album.

“We have to pay attention to who is showing up in the stores because it has changed drastically,” Muratore said. “If there were more allocation, this could have been the biggest Record Store Day ever.”

The International Music Summit (IMS) will return to Dubai this fall. This will be the electronic music industry conference’s second time in the United Arab Emirates after debuting in Dubai in late 2024. The event will happen November 13-14 at 25hours Hotel One Central. At this year’s conference, IMS will gather industry figures from the […]

LONDON — Manchester’s Co-op Live Arena has teamed up with Adidas and Abbey Road Studios for the launch of a new recording studio inside its premises.

The Adidas Originals Recording Studio is situated inside the U.K.’s largest music arena and has been designed as “a vibrant hub for emerging musical talent and young creative communities.” The studio has been engineered by Abbey Road’s technicians and sound engineers.

The studio in Manchester, England will be available to local musicians from August onwards. The initiative is launched in conjunction with a number of existing schemes, including Abbey Road’s Amplify and Equalise programmes, which hosts a number of panels, workshops and recording opportunities at the iconic London studios each year.

Trending on Billboard

Factory’s International’s Factory Sounds initiative, which provides financial support and mentorship to underrepresented groups in the Greater Manchester area, is also involved with the project. Courteeners frontman Liam Fray, who was born and raised in Middleton, Manchester, opened the studio with an acoustic live performance and praised the space and the opportunities it may provide: “To have something of this level up here that is a focal point in Manchester opens up the industry and takes it to a wider audience.”

Despite a rocky, delayed opening, the Co-op Live Arena has become a key venue on the U.K.’s touring circuit, with a number of huge acts set to perform there this summer, including Bruce Springsteen, Olivia Rodrigo, Tyler, the Creator, Massive Attack and more.

Sally Davies, managing director of Abbey Road Studios, said in a statement: “The launch of the adidas Originals Recording Studio is a world-first collaboration creating a new, Abbey Road-engineered recording space beyond the walls of our home in London.”

“We are enormously proud to partner with Adidas, Co-op Live and Factory International to create a new platform for talent in Manchester and the North-West, expanding our mission to enable and empower the global community of music makers and creators, and shape the future of music making.”

LONDON — A new Tube map showcasing the breadth of London’s artists and music venues has been published as part of a campaign championing the capital’s grassroots scene.

The map highlights record shops, nightclubs and historic locations across the city, as well as venues such as XOYO and Electrowerkz to institutions such as the Barbican. London-raised artists including Dua Lipa, Dave and recent Billboard U.K. cover star Loyle Carner also feature.

Each Underground line has been reimagined as a different aspect of the city’s music scene, with the Jubilee line displaying London-made albums, the Metropolitan line showing independent record labels, and the District line listing “25 artists to see in 2025.” The iconic map was designed by Harry Beck and first came into use in 1933.

Trending on Billboard

London mayor Sir Sadiq Khan and Transport for London (TfL) joined forces with media leaders to devise the map as part of the London Creates campaign. Over the next month, it will be displayed at digital exhibition space Outernet London in Tottenham Court Road.

In a statement, Khan said: “London’s grassroots music scene is renowned around the world. From providing opportunities for talented aspiring artists to develop their trade, to giving Londoners a great night out, our venues are an essential part of our life at night and provide a huge boost to our economy.

“However, they have faced huge challenges in recent years, which is why we’re joining with partners across the capital to champion all parts of London’s grassroots music scene. This special edition Tube map is a great way to highlight what a huge impact the scene has on our capital, as we continue to do all we can to support venues and build a more prosperous London for everyone.”

Mark Davyd, founder and CEO of Music Venue Trust, added: “London is one of the world’s great music cities, constantly reinventing itself with new sounds, new genres, and incredible new artists. The network of grassroots music venues in London are an essential part of what makes the capital’s music thrive, delivering an extraordinary range of music, community and life changing experiences at affordable prices.”

According to City Hall, London is home to 179 grassroots music venues, which in the last year have welcomed more than 4.2m audience members, hosted performances by more than 328,000 artists, employed nearly 7,000 people and contributed £313m ($417m) to the economy.

The map was formally published in the Metro newspaper yesterday (May 13). Further information about the campaign can be found at the newspaper’s official website.

Bill Ackman, whose hedge fund Pershing Square Capital has been among Universal Music Group’s largest investors, said he will resign from his seat on UMG’s board of directors effective Wednesday “due to new executive and board obligations arising from his recent investments,” according to a company statement. In a brief announcement posted Wednesday hours ahead […]

Chinese streaming platform Tencent Music Entertainment grew its stake in the world’s largest music company, Universal Music Group (UMG), by picking up a direct 2% equity holding worth $327 million in March, the company said on Tuesday (May 13).

While it did not identify the seller — described in Tuesday’s filings only as “one of our associates” — Pershing Square sold 50 million shares of UMG on March 13, raising about $1.3 billion, according to filings and research reports. Tencent Music and Pershing Square did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The news means that Tencent Music and UMG each own notable stakes in each other’s companies, as UMG owns a 0.79% stake in TME as of Dec. 31 that’s currently worth $181.2 million.

Trending on Billboard

Tencent Music has been an investor in UMG since March 2020, when it joined a consortium of investors led by its parent company, Tencent Holdings. That consortium accumulated a 20% stake in UMG from UMG’s parent company, Vivendi S.A., between 2020 and 2021, of which Tencent Music owned a 10% share, according to filings.

This March, that consortium “completed a transfer of the UMG shares held by the consortium to its members,” which resulted in Tencent Music acquiring a direct 2% equity interest in UMG, according to its annual report.

Tencent Music, which reported first-quarter revenue of 7.36 billion Chinese yuan ($1.01 billion) on Tuesday, recognized “other gains” worth 2.44 billion Chinese yuan (US$336 million), of which the UMG stock comprised 2.37 billion Chinese yuan (US$327 million), according to filings.

Pershing Square has been an investor in UMG since 2021, and though the mid-March stock sale reduced its stake in UMG to 4.9% from 7.6%, the music company remains the hedge fund’s largest single holding, comprising 17% of its capital.

The sale came ahead of Pershing Square’s plan to register its UMG shares in the United States in September. Pershing Square head and UMG board member Bill Ackman has advocated for the company to move its primary listing from the Euronext Amsterdam stock exchange to a U.S.-based exchange, saying it would add value for the company.

Jeremy Sirota will leave Merlin at the end of the year, the licensing organization announced on Tuesday (May 13).

Sirota has served as CEO since 2020, guiding Merlin as it steers digital music licensing for independent labels and distributors. During Sirota’s tenure, Merlin reached new deals with Apple, Audiomack, Canva, Peloton, Snap, Twitch and more.

In a statement, Darius Van Arman, who is both chairperson of Merlin and co-founder/co-owner of Secretly Group, called Sirota “an extraordinary CEO” who brought “great focus, tremendous energy and brilliant thinking to one of the most important and challenging roles within the independent community.”

“His work and leadership has Merlin more prepared than ever to manage an increasingly complex music licensing landscape and to achieve our mission of enabling greater independence for all Merlin members,” Van Arman continued.

In his own statement, Sirota called helming Merlin “the privilege of a lifetime.” He added that the organization continues “to be the most important organization representing independents” and that it “has a bright future.”

Trending on Billboard

Sirota previously worked as a tech lawyer before spending nine years at Warner Music Group and then jumping to Facebook Music.

That experience “gave me the ability to relate to people at different levels in the business, whether it’s a product manager at a digital platform, or an engineer who’s now a founder of a startup, or it’s a member who runs a metal label,” he told Billboard last year. “I’ve always been on the service side, and that’s always been the through line.”

During Sirota’s time as CEO, Merlin added over 100 members. In addition, the organization launched Merlin Engage, a program to mentor the next generation of women executives, and Merlin Insights, to help members analyze the deluge of data that’s available in world of streaming.

“We now have a data operations team to make sure that all trends data is being delivered in the right format,” Sirota explained in 2024. “Our market share on some of these platforms is significant — more than just the 15% we talk about. So we have this incredible wealth of data. We have the ability to pull out interesting stories that help our members — things they don’t know because they’re not on the ground.”

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio