Billboard Espanol

Trending on Billboard

Romeo Santos arrives wearing a face mask and a hoodie. He’s not sick, just determined to avoid being recognized as he enters our New York studios, and immediately heads to his dressing room with his small entourage. Minutes later, Prince Royce walks through the door, just as quickly and discreetly, with a cap under the hood of his sweater covering half his face.

The two have been seen together in the past, but only as friends on social media. Today, the last Wednesday of October, they’re here to announce something completely different: Romeo Santos and Prince Royce, the “king” and “prince” of bachata, respectively, are finally collaborating, not on a single song, but on an entire album.

Their collaboration has been the best-kept secret in Latin music in years. Appropriately titled Better Late Than Never, the 13-song album will arrive Nov. 28 on Sony Music Latin, where only a small group of people knew of its existence.

Close friends and family were also unaware. (Coincidentally, Royce’s brother, who works as a photographer in New York, only learned of the project when he joined the team that shot the cover for this Billboard Español story and saw both artists’ names on the call sheet.) Many of the musicians who played on the album think it’s by one or the other, since both artists deliberately summoned their sidemen separately and were never seen together in the studio.

The result is pure synergy: “There’s no one taking center stage here,” Santos says. “There isn’t a song where he sings more than me or me more than him.”

I listened to the album the day before, when Santos — as he’s done in the past with Billboard — picked me up in a Cadillac Escalade V and played it for me from beginning to end, responding to my questions and reactions with the joy of someone who knows he has something special in his hands. He’s never been one to share files of his work through email before their release, and he certainly wasn’t going to risk it this time.

Better Late Than Never has the essence of Santos and Royce throughout but also offers something fresh for both artists. There are classic bachatas, more modern takes and mostly romantic lyrics, and the fusion of their recognizable voices is captivating from the first track, which shares the album’s title.

Songs such as “Dardos” and “Jezebel” stand out, the latter displaying strong R&B influences, as well as “Ay San Miguel,” a Dominican palo, and “Menor,” a surprising first collaboration for Santos with an emerging talent, Dalvin La Melodía — who also hadn’t yet been informed about Royce’s participation.

Santos and Royce wrote four of the songs together, starting with “Mi Plan,” penned during a friends trip to St. Barts in 2023, and “Better Late Than Never,” “Jezabel” and “Loquita Por Mí.” The rest were mostly written by Santos, always with Royce’s participation and honest input. But the seed of this production has been germinating since at least 2017, when they recorded the first of three failed attempts that will likely never see the light of day.

“I don’t want to sound cliché or overly religious, but God’s timing is perfect,” Santos says, explaining why now was the right time. “When we started recording the first song seven years ago, there was a little resistance from both of us. I felt convinced at the time… the vibe was there, but then we started evaluating it and [realized], ‘Mmm, this is not the song.’”

“There was a moment where I said, ‘Man, are we ever going to find that fusion, that muse, where we both feel comfortable and can say, ‘This is great?’ ” Royce adds. “And it wasn’t that I doubted it, but it required going in and really delving into it — and suddenly there was a switch.”

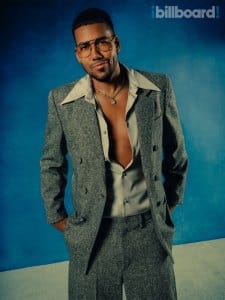

Santos

Malike Sidibe

The launch strategy was equally secretly planned. On Oct. 31, Halloween, Santos, unrecognizable in an Ace Ventura costume, announced on his Instagram account “new album November 28” — with a link in his bio to preorder it — along with a video of him partying in New York with an album in his hands. Days later, on Nov. 10, a massive listening party for his fans scheduled for Nov. 26 at Madison Square Garden was announced on Univision shows such as Despierta América and El Gordo y La Flaca and radio station WXNY-FM (La X 96.3) New York, where listeners could call in to win tickets. According to Santos’ publicist, at the time of the announcement, 7,000 people were online looking for tickets, all assuming that “it’s a [solo] Romeo album.”

Of course, there were no singles or previews. A music video featuring two songs — “Estocolmo” and “Dardos” — will be released simultaneously with the album. To communicate with the director, they used the code names “Batman” and “Robin.”

The collaboration between the two powerhouses is highly anticipated by bachata fans, and the fact that the project wasn’t rushed gives it new urgency and importance. Superstars of the genre from different generations, they are also very different in style — Santos with his sweet, high-pitched voice and use of traditional guitars; Royce with his light lyric tenor and a more pop/urban sound. And both have redefined the genre. Santos, 44, revived bachata when it was considered traditional regional music, giving it a sensual twist with touches of contemporary New York that captivated a new generation. Royce, 36, came later with bachata versions of Motown classics.

Santos rose to fame in the mid-1990s as leader of the group Aventura before launching a brilliant solo career in 2011 with Fórmula, Vol. 1, the longest-running bachata album by a solo artist on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart (17 weeks at No. 1); more recently, he was No. 2 on the Top Latin Artists of the 21st Century list (behind only Bad Bunny). Royce debuted in 2010 with a self-titled set that reached No. 1 on Top Latin Albums, which he has topped five times.

Both born in the Bronx to Dominican parents (except for Santos’ mother, who is Puerto Rican), they met at a family party. “Aventura was huge at the time,” Royce recalls. “I was in my room playing PlayStation. I heard the revolú [commotion], so many people outside. I went out and took a picture [with him],” adding that he was starstruck by the singer’s presence. Now, “This is a full-circle moment. What Romeo and Aventura have done has inspired me.”

“Romeo Santos and Prince Royce are two wonderful artists, two exceptional professionals — and even better human beings — who have dedicated their careers to bringing bachata to the world,” Afo Verde, chairman/CEO of Sony Music Latin Iberia, told me days after the interview. “Each of the songs on this brilliant album reflects the talent, creativity, passion and dedication of both of them. We can’t wait for all the fans to experience this magical album they’ve created together.”

Sitting down to talk for the first time about their most closely guarded secret in an exclusive interview with Billboard Español, Santos and Royce delve into the project, their friendship and the future of the genre that made them famous.

Prince Royce

Malike Sidibe

To begin, who approached whom? Who said, “Let’s do it”?

Romeo Santos: I’d like to take credit, but the truth is, the first person to mention the idea of recording not one, not two, but a whole album, was this gentleman right here. (Gestures to Royce.) And that was literally seven years ago, right?

Prince Royce: A long time ago, yes. I felt a lot of pressure from the public, really. If we make a song, what will it be? It can have pop elements, it can have very traditional elements, it can be a fusion. And I was thinking about how to fuse these two worlds, which, although it’s bachata, are two different styles of bachata. I always thought, “Man, how iconic would it be if we made an album, if we could give everyone these different kinds of flavors and colors?”

Santos: Yes, because that’s a valid point. When he says “the pressure,” it’s like a song will have an audience who will say, “I like this one,” but there will be another type of fan who will say, “Yes, but it’s too slow.” There are those who say, “Yes, but it’s too fast.” “Yes, but it doesn’t have that bitterness or it’s too depressing.” We have a production that fills all the gaps.

You recorded three previous tracks — one in 2017 for Golden, another in 2022 for Fórmula, Vol. 3 and a third later — and none of them were released. After three attempts, what motivated you to keep trying and not give up?

Santos: I think we started evaluating the three songs we had already recorded. “Where was the problem? How could the chorus of these three songs be improved? Was it the verse, the arrangement?” And at least I had the goal of making the songs feel organic, not like we took a song, sent a verse to Royce or vice versa, just to say we collaborated. I think it had to happen this way: three failed attempts to lead to this production. I don’t think I could have worked with Royce in a more ideal way. The best songs we were able to create are on this album.

Royce: I think for me it was, “We shouldn’t rush things.” Nowadays a lot of people lack patience, and I’ve always been very patient. I’m not a quitter, and he’s definitely not a quitter.

Santos: And you know what I respect? He was honest with me about those three songs. I mean, if he had been a hypocrite and told me, “They’re great,” this project wouldn’t have happened. But he was like, “I don’t know, loco, they’re OK, but do you think so?” So I kind of analyzed them. And honestly, every time I presented him with a song, I felt it was better than the last one.

How is it possible that none of this leaked in all these years?

Santos: Well, I’ll just say that in the world of privacy, I’m an expert. I feel very comfortable, even if it’s a little stressful, working on projects with the element of surprise. I’m used to it; I don’t like to prepare people.

Royce: In my case, I just don’t want to jinx it either. I know how he works, I’ve known him for many years. For me it was such an important project that I wanted the element of surprise, I wanted to surprise the audience, I wanted to focus on the project without anyone interfering and simply work.

Santos: Another factor was that we genuinely posted photos and videos together because we were hanging out. I think that when people saw those pictures and didn’t hear any music, they kind of overlooked it. And I didn’t know at the time that this was also what would work as a strategy for us. We managed to keep it a secret for several reasons. Also because technology has changed so radically these days that you can record a production, an album, whatever at home. We didn’t go to public studios; everything was recorded during vacations — we were in a villa with our friends and family, in my home studio in New York. We visited his house many times. That part was easy, honestly.

Royce (left) and Santos

Malike Sidibe

Tell me about “Batman” and “Robin.”

Santos: Ah, that was the code.

Royce: I called it the “Bora Project” with my small team.

Santos: We created this “Batman” and “Robin” thing, but for different aspects; for filming music videos, talking to the director: “Remember, Royce is Robin, I’m Batman.” Until it became second nature. Now I say to him: “What’s up, Robin?”

The fact that the record label hasn’t even heard the album speaks volumes about the creative freedom the label has given you to work together.

Santos: Look, I’m very grateful to Afo [Verde], to the whole Sony team really, but Afo is one of those people who respects the creative side of artists. And I remember sending Afo a message about two months ago, more or less, saying, “Brother, I have a project that I think is going to excite you. You’re going to love it, and I want to share this project with you. I want you to listen to it, to be one of the first.” Afo tells me, “I knew you were planning something,” because my last post was, if I’m not mistaken, on Jan. 8 of this year, and I’ve been ghosting on social media.

How easy or difficult was it working together as two big artists with such distinctive styles?

Royce: From the moment we made that first song [that actually worked], everything flowed for me. It was like there was a whole year where I felt like we were creating something incredible. I was so happy. And I really admire how he pushed me in the studio.

Santos: Thank you. I’m kind of a maniac.

Royce: I hadn’t felt like that in a long time. The fact that I thought I was doing well and [he’d tell me], “No, you can do better, bro,” and just keep at it…

Santos: And vice versa, because I’m so used to directing myself that sometimes you overlook certain things you stop doing as a performer. … The interesting thing about this project is that it has his essence, my essence, but musical proposals that neither of us has offered to the fans before.

Who was more involved in the production?

Santos: I would say I was… [But] I reiterate: He was very key because he trusted me, but also kind of challenged me. When I showed him a song, he was very honest, as he’s always been. So I went in already with that challenge.

What new elements will the audience hear?

Royce: There are new elements like “Dardos,” which has a lot of fusion. There are Afrobeat vibes, tropical vibes, different types of guitars, violins. [The song] “Better Late Than Never” starts off very pop, a cappella. And I think there are many elements, within bachata as well, in the way the guitar is played; there’s a bit of a rock flow.

Santos

Malike Sidibe

What did you think when you heard the album for the first time in its entirety?

Santos: We hugged with happiness.

Royce: I was jumping around, I was tipsy. … I was super excited. For me, it has been an honor to record this album. It has been a very beautiful experience in the studio as well.

Santos: You know what I used to tell him? “This pendejo sings beautifully!” Because I was listening to him from a different perspective. I love producing, and when you create a melody thinking of someone else, in my case, I enjoy it more than I enjoy singing it myself. And sometimes he sang a melody even better than what I envisioned.

Were you already a fan of Prince Royce’s music?

Santos: There’s a mutual respect. I’ve always told him about the songs I love from his repertoire. For me, “Incondicional” is one of those songs that, if you ask me what Romeo hasn’t done in bachata, both with Aventura and as a solo artist, when I heard that song I said, “F–k, mariachi with bachata!” That was great.

Royce, is there a song by Romeo you wish you had written?

Royce: There are many. I’ve always been a fan of “La Novelita” by Aventura. “Infieles.” “Eres Mía”… I think he’s a walking encyclopedia of bachata; he knows every bachata song and has a lot of musical knowledge. And he’s a genius with lyrics, truly.

As friends and colleagues, do you ever call each other for advice?

Santos: Of course. We’ve talked a lot long before this project. It’s a truly genuine friendship.

Prince, what’s the best advice you remember Romeo giving you?

Royce: There are many that I probably can’t say on camera. No, just kidding. (Laughs.) In terms of advice — not just musical; it could be business, it could be personal — we’ve had many conversations and he’s always been, I really mean it, very real with me… And I’ve always respected that.

Santos: I can tell you that one piece of advice he gave me once was, “Don’t take things so seriously.” I have that problem. Sometimes we forget to have fun. Especially when you have a plan, the rollout, marketing, a million things, and I feel like he has that quality. He loves what he does, just like I do, but maybe I’m too… What’s the word?

Royce: Particular, detail-oriented…

Santos: Yeah, sometimes that kind of takes away the fun.

Royce

Malike Sidibe

Let’s talk about the state of bachata. How do you see the genre right now?

Santos: How far the genre has come is impressive, especially when you see artists who aren’t bachata singers navigating this genre of heartbreak. When I listen to Rosalía, Manuel Turizo, Maluma, Shakira, Rauw Alejandro, Karol G, that’s an excellent sign that good work has been done since the beginning.

However, a superstar on the level of Romeo Santos and Prince Royce hasn’t emerged. Why do you think this has happened?

Santos: I think there are a lot of Prince Royces and Romeos in an attic, in a basement, creating the new sound. The thing is, this business isn’t easy. And when I say it’s not easy, it’s not easy for us either. There’s a very essential key that few apply, and that’s perseverance. If you analyze my career, people remember Aventura from “Obsesión,” but we’d been hard at work six years prior to that.

Royce: I think a lot of people always see the success but they never see the failures, what didn’t happen, the doors you knocked on. And I think that nowadays it’s very important to be different… and to bring something that Romeo Santos didn’t bring and that Prince Royce didn’t bring, because they’re already here.

Going back to your wonderful project, an album is usually followed by a tour. Do you plan to go on the road together? What do you envision for that show?

Santos: Obviously, yes, we are considering a tour, God willing, and a worldwide one so people can enjoy both of our repertoires. And when it happens, God willing, we don’t want it to feel like a show where he goes onstage, sings his setlist, then I sing mine. No. We want it to be an experience where, whether you’re a fan of Royce and me or just a fan of him or just of me, it’s a musical journey through both of our repertoires.

What would you say to Prince Royce fans who aren’t Romeo Santos fans, and to Romeo Santos fans who aren’t Prince Royce fans?

Royce: Well, personally, I think they’re going to become fans of all of us.

Santos: You want to know what I’d tell his fans? That they’re going to have to put up with Romeo! (Laughs.) No, but seriously, this is a treat, a gift for both sets of fans, because I think — and I don’t want to sound repetitive — that it’s a production where each song is dedicated to different styles, to his essence, to mine. But there’s something else you’ll notice about it: There’s no one taking center stage here. There isn’t a song where he sings more than me or me more than him. Maybe your favorite part of this particular song is Royce’s chorus, and maybe your favorite part is the pre-hook I did, but I hope you like it, that it evokes some kind of emotion in you in a positive way, because we made it with all the love we could put into a project.

It’s 2 a.m. on a May morning in Aguascalientes, Mexico, long past most people’s bedtimes. But inside the Palenque of Feria de San Marcos — a venue in this central Mexican city — Carín León is entering the third hour of a performance where he has sung nonstop while pacing the small 360-degree stage like a caged lion.

Palenques, found in most Mexican cities and towns, were originally designed and used for cockfighting, and most have been transformed into concert venues that put artists in shockingly close proximity to their fans, with no ring of security around the tiny stage. The palenque circuit is de rigueur for Mexican artists, even a superstar like León — a burly man who tonight looks even bigger thanks to his ever-present high-crown cowboy hat.

Nearly 6,000 fans surround him in arena-style seating, the steep, vertical layout allowing everyone a close view of the man below, flanked by his backing ensemble: a norteño band with electric guitars, a sinaloense brass section, backup singers and keyboards — nearly 30 musicians in all, who wander about, grab drinks, chat and return to the stage throughout the show. León leads the organized chaos, traversing repertoire that, during the course of the evening, goes from corridos and norteño ballads to country and rock’n’roll.

“I think it’s the most Mexican thing possible in music, a palenque. I always say you have to see your artist play in a palenque to understand it,” León tells me a few hours before the show. He has been playing them for years throughout the country, like most regional Mexican artists do. They’re places of revelry and drink, a rite of passage, and the place to test new sounds.

“As artists, we appreciate that experience,” he adds. “We love it because you have people so close to you. You can be with them, have drinks with them — it’s a very interesting artist-fan communion.”

We’re chatting between sips of tequila at a country house on the outskirts of Aguascalientes, and despite the stifling afternoon heat, León keeps his hat on, looking stately in his boots and black jacket with metal buckles. Soft-spoken but emphatic, the 35-year-old música mexicana star alternates between Spanish and English, which he speaks with the American-sounding but accented cadence of someone who learned it by ear from transcribing songs by hand, but never in a classroom.

“I always had trouble with my accent when I sang,” he says. “But I didn’t want to lose the accent because it makes you unique. [An accent] is more valid now. I always want to ensure the music is good, refine it, make it better. But we’re coming from the 2000s, when music [production] was perfect. Now value is given to what’s natural, and that includes having an accent.”

Christopher Patey

While at his core León is a regional Mexican artist who performs contemporary banda and norteño, he loves collaborating with artists spanning many genres and incorporating regional sounds from around the world into his music: Spanish flamenco, Colombian vallenato and salsa, Puerto Rican reggaetón. And as he blends these sounds in unexpected ways, León has found an avid and growing audience.

In 2024, he crisscrossed the world on his Boca Chueca tour, playing 81 palenque, arena and stadium dates in the United States and Latin America. Of 1.3 million total tickets sold, according to his management, 374,000 were reported to Billboard Boxscore for a gross of $51.2 million, making it one of the year’s most successful Latin tours. This year, he’s scheduled to play 40 more shows, including Chilean and Colombian stadiums, Spanish arenas and German theaters — a leap few regional Mexican acts, whose touring is usually restricted to the United States and Mexico, have accomplished at such a scale.

But León has transcended mere geographic borders. Last year, after releasing singles with country star Kane Brown and soul musician Leon Bridges, León became the first artist to perform mainly in Spanish at the Stagecoach country music festival, just a couple of months after making his Grand Ole Opry debut. On June 6, he became the first regional Mexican artist to play CMA Fest, as a guest of Cody Johnson, who invited him to perform the bilingual “She Hurts Like Tequila” with him as part of his set at Nashville’s Nissan Stadium.

“What struck me most was how effortless it felt,” Bridges says of working with León on the bilingual duet “It Was Always You (Siempre Fuiste Tú).” “We come from different musical backgrounds, but the emotion, the storytelling — that was shared. Collaborating with him wasn’t about chasing a fusion — it was about two artists trusting each other to make something honest. Going down to Mexico and being immersed in his world was a powerful reminder of how universal that connection through music really is.”

From a purely commercial standpoint, León has no need to take musical risks like this beyond the Latin realm. In the past five years alone, he has notched three entries on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart, including Colmillo de Leche (2023) and Boca Chueca, Vol. 1 (2024), which both reached the top 10. He has placed three No. 1s on the Latin Airplay chart, seven No. 1s on Regional Mexican Airplay and 19 entries on Hot Latin Songs, including three top 10s. He’s a widely sought-after collaborator for pop stars (Camilo, Maluma, Kany García, Carlos Vives), Spanish stars (Manuel Carrasco, El Cigala), Mexican legends (Pepe Aguilar, Alejandro Fernández) and fellow current chart-toppers (Grupo Firme, Gabito Ballesteros) alike.

But regardless of what sounds he’s working with, or whether his collaborator is an established name or an untested act (a particular favorite of his), León knows what he likes. That confidence is at the core of his and manager Jorge Juarez’s strategic plan to make him a truly global artist — and for the past year, they’ve set their sights on country music, hoping to bridge the divide between two genres that, despite their different languages, are in fact remarkably similar.

“It’s something that fills me with pride and something that’s been very difficult to achieve as a Mexican and as a Latin: to reach the center of the marrow of this country movement,” León says. “To get to know this [country music] industry and start moving the threads to act as this missing link between regional Mexican and country music.”

Carín León photographed April 29, 2025 at Gran Ex-Hacienda La Unión in Aguascalientes, Mexico.

Christopher Patey

León first tested the country waters back in 2019 with a Mexican/country version of Extreme’s “More Than Words,” recorded in English and Spanish. Though it now has 14 million streams on Spotify, “it’s kind of lost because there was so much other stuff happening at the time,” he says. It was a risky move, especially coming when León was not yet the established star he is today. But to him, it was one worth taking.

“It was the perfect excuse to show something different,” he says. “And it was amazing. It was so liberating. Because I was trapped in this box that was regional mexicano at that time, and [this song] was very fun for me.”

Country and regional Mexican are, truly, natural siblings. Both genres are anchored in storytelling, with acoustic instrumentation and guitars central to their sound. Boots, hats and fringe jackets are staple outfits for artists and fans alike. And though they stem from different cultures, both are, as León puts it, “roots genres” with their foundations in regional sounds.

Unsurprisingly, other Latin artists have forayed into country before — but none have brought León’s existing level of Latin music stardom, nor have they generated the buzz and impact that he has since releasing his first country team-up, “The One (Pero No Como Yo),” with Brown in March 2024. Since then, he has spent weeks in Nashville, working with local producers and songwriters for a country-leaning album featuring other major names that’s slated for a 2026 release.

For country music, that’s good news. According to the Country Music Association’s 2024 Diverse Audience study, 58% of Latino music listeners consume country music at least monthly, compared with 50% when the last study was conducted in 2021. Finding the right opportunity to tap that market had long been in the Grand Ole Opry’s sights. “And then,” says Jordan Pettit, Opry Entertainment Group vp of artist and industry relations, “the opportunity with Carín came up.”

At León’s Opry debut in 2024, “we had a lot of audience there, more than normal,” Pettit recalls. “The show itself absolutely blew my expectations.” The plan had been for León to play three songs, but the crowd clamored for more, and the musician obliged with a fourth. “I can think of only one or two occasions in my seven years here where I’ve seen an artist get an encore,” Pettit says. “It was really, really awesome to see the worlds collide.”

León’s worlds have been colliding since he was born Óscar Armando Díaz de León in Hermosillo, Mexico, a business hub and the capital of the northwestern state of Sonora, located 200 miles from the U.S. border at Nogales, Ariz. That proximity, coupled with his family’s voracious appetite for music, exposed him to a constant and eclectic soundtrack that ranged from Cuban troubadour Silvio Rodríguez and corrido singer Chalino Sánchez to country stars Johnny Cash and George Strait to rock mainstays like Journey, Paul McCartney and Queen.

“What’s happening now in my career is the result of the music I ingested since I was a kid,” he says. “Music gave me the incentive to learn about many things — the origin of other countries, political movements linked to music, cultural movements. I’m very freaky about music. Everything I have comes from the music I listened to.”

When León finally started dabbling in guitar, he gravitated to the music closest to his roots, regional Mexican, and eventually adopted his stage name. By 2010, he was the singer for Grupo Arranke, which through its blend of traditional sinaloense banda brass and sierreño guitars eventually landed a deal with the Mexican indie Balboa. After a slow but steady rise, Grupo Arranke garnered its sole Billboard chart entry, peaking at No. 34 on Hot Latin Songs in 2019 with “A Través del Vaso,” penned by veteran songwriter Horacio Palencia.

Then the coronavirus pandemic hit, and León switched gears: He went solo, signed to indie Tamarindo Recordz and began releasing music at a prolific pace, launching what he now calls his “exotic” cross-genre fusions.

He scored his first top 10 on a Billboard chart with “Me la Aventé,” which peaked at No. 6 on Regional Mexican Airplay in 2019. But his true breakouts were two live albums recorded and filmed in small studios during lockdown, Encerrados Pero Enfiestados, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (Locked Up, but Partying). The bare-bones sets, featuring León singing and playing guitar with a stripped-down accompaniment of tuba and guitar, struck a powerful chord. At a time when teenage performers with gold chains and exotic cars were propelling corridos tumbados and música mexicana with hip-hop attitude up the charts, this 30-year-old relative unknown with a poignant tenor that oozed emotion was performing regional Mexican music with a Rhodes organ, a country twang and, with his cover of ’90s pop hit “Tú,” a female point of view. No one else sounded like him.

Christopher Patey

Those acoustic sessions “were the first things I realized could make the audience uncomfortable [and] question what they were hearing,” León recalls. “Wanting everyone to like you works, but it doesn’t let you transcend. I think things happen when you change something — for good or bad — and you get that divided opinion. All my idols — Elvis, Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash — were people who swam against the current. And not in a forced way, but in a sincere way, exposing vulnerabilities. We knew it was good stuff. And things began to happen.”

During the pandemic lockdown, León had the time and creative space to experiment and explore a new openness within regional Mexican music, a genre where artists used to seldom collaborate with one another. In 2021, he notched his first No. 1 with “El Tóxico,” a collaboration with Grupo Firme that ruled Regional Mexican Airplay for two weeks.

Then, Spanish urban/flamenco star C. Tangana DM’d him on Instagram and invited him to collaborate on “Cambia!,” a song from Tangana’s acclaimed album El Madrileño that also featured young sierreño star Adriel Favela and can best be described as a corrido flamenco. The track “blew my mind,” León says — and exposed him to a completely different audience. “It taught me divisions are literally only a label. When I heard that album, I understood music has no limits. C. Tangana is to blame for what’s happening with my music now.”

Collaboration requests from artists seeking León’s unique sound (and sonic curiosity) started to flow in at the precise time that he was itching to explore and globalize his music. In 2022, after recording the pop/regional Mexican ballad “Como lo Hice Yo” with Mexican pop group Matisse, he met the band’s manager, Jorge Juárez, co-owner of well-known Mexican management and concert promotion company Westwood Entertainment. The two clicked, and when León’s label and management contract with Tamarindo expired in early 2023, he approached Juárez.

“There comes a time when managers and the artist have to be a power couple,” León observes. “I found the right fit with Mr. Jorge Juárez. He’s a music fiend; he has a very out-of-the-box vision. That’s where we clicked. And he had huge ambition, which is very important to us. He’s the man of the impossible. We want to change the rules of the game.”

In León, Juárez says he saw “a very versatile artist who could ride out trends, who could become an icon. He wasn’t looking to be No. 1, but to be the biggest across time. He had so many attributes, I felt I had the right ammunition to demonstrate my experience of so many years and take him to a global level.”

Juárez, who shuttles between his Miami home base and Mexico, is a respected industry veteran who has long managed a marquee roster of mostly Mexican pop acts including Camila, Reik, Sin Bandera and Carlos Rivera. He’s also a concert promoter with expertise in the United States and Latin America. He sees León as having the potential to become “the next Vicente Fernández,” he adds, referring to the late global ranchero star.

Because León had parted ways with Tamarindo, which kept his recording catalog, he urgently had to build a new one. He and Juárez partnered in founding a label, Socios Music, and began releasing material prolifically, financing the productions out of their own pockets. Since partnering with Juárez, León has released three studio albums: Colmillo de Leche and Boca Chueca, Vol. 1, which both peaked at No. 8 on Top Latin Albums, and Palabra de To’s, which reached No. 20. Beyond the catalog, they had three other key goals: finding a tour promoter with global reach, building the Carín León brand and expanding into country.

AEG, which León and Juárez partnered with in 2023, could help with all of it. Last year, the promoter booked León’s back-to-back performances at Coachella and Stagecoach — making him one of very few artists to play both of the Southern California Goldenvoice festivals in the same year — as well as his slot opening for The Rolling Stones in May in Glendale, Ariz. AEG president of global touring Rich Schaefer says they sold over 500,000 tickets for León headline shows in the United States since they started working together, including a 2024 sellout at Los Angeles’ BMO Stadium.

“There are few artists who put out as much music as Carín does on a regular basis,” Schaefer adds. “He’s able to sing and speak fluently in two languages, which has already opened a lot of doors both in the States and abroad. Our team works very closely with Jorge and his team, and he has a deep understanding of how to approach international territories. With a little luck, Carín is poised to take over the world.”

Carín León photographed April 29, 2025 at Gran Ex-Hacienda La Unión in Aguascalientes, Mexico.

Christopher Patey

That international viewpoint also informed León’s approach to recording. When Juárez set out to unlock country music for his client, he first contacted Universal Music Publishing Group head Jody Gerson — “our godmother,” as Juárez likes to say. “She opened so many doors to us.”

Gerson first met León in 2023, after Yadira Moreno, UMPG’s managing director in Mexico, signed him. “It was clear from my first meeting with him that he possessed an expansive vision for his songwriting and artistry that would take him beyond Mexican music,” Gerson says. “Before signing with us, he wanted to make sure that we were aligned with his ambitions and that he would get meaningful global support from our company, specifically in Nashville. Carín actually grew up listening to country music, so his desire to collaborate with country songwriters is an organic one.”

Beyond opening the door to working with Nashville producers and songwriters, Gerson also connected Juárez and León with Universal Music Group chief Lucian Grainge, who in June 2024 helped formulate a unique partnership between Virgin Music Group, Island Records and Socios Music. Through it, Virgin and Island distribute and market León’s music under Socios, with Virgin distributing and marketing to the U.S. Latin and global markets and Island working the U.S. mainstream market.

The agreement encompasses parts of León’s back catalog as well as new material, including 2024’s Boca Chueca, Vol. 1, which featured his bilingual collaborations with Brown (“The One [Pero No Como Yo],” which peaked at No. 46 on Hot Country Songs) and Bridges.

He plans to deliver Boca Chueca, Vol. 2 before the end of the year and just released a deluxe version of Palabra de To’s that includes new pairings with Maluma (their “Según Quién” topped the Latin Airplay chart for four weeks in 2023 and 2024) and first-time duets with ranchera star Alejandro Fernández and flamenco icon El Cigala.

While flamenco is another passion point for León, the country album — his “first magnum opus,” he says — is his most ambitious goal. Already, he has worked in Nashville with major producers and songwriters including Amy Allen, Dan Wilson and Natalie Hemby. On the eclectic project, he says, “Some stuff sounds like James Brown, some stuff sounds like Queen, some stuff sounds like regional Mexican with these corrido tumbado melodies, but in a country way. It’s very Carín. It’s what’s happening in my head and in my heart.” He won’t divulge all of its guests just yet, but he says it includes friends like “my man Jelly Roll” and other big stars he admires.

It’s new territory for a Latin act, and León is acutely aware of the fact. But he’s approaching it from a very different point of view. “I’m not a country artist,” he says flatly. “I’m a sonorense. I have regional Mexican in my bones. But I love country music, and I’m trying to do my approach with my Mexican music and find a middle point. It’s not easy. You have a lot of barriers because of the accent, because of the language, the racial stuff.”

For some successful regional Mexican artists who tour constantly and make top dollar, the trade-off is not worth it; financially speaking, they don’t need to open new territories or genres and the audiences that come with them. But for León, “the money trip passed a lot of years ago,” he says with a shrug, taking a last sip of tequila and adjusting the brim of that ever-present accessory he shares with his country friends. “I need to change the game,” he adds. “I’m hungry to make history, to be the one and only. I’m so ambitious with what I want to do with the music. It’s always the music. She’s the boss.”

The 2025 Argentina Music Report from the Argentine Chamber of Phonogram and Videogram Producers (CAPIF) shows that streaming is still dominating the country’s music industry, making up 79% of total recorded music revenue in 2024.

Within the digital segment, subscription-based streaming leads with 65% of the revenue, solidifying itself as the main source of music monetization in Argentina. Meanwhile, ad-supported streaming accounted for 35% of the total.

“For the first time since emerging from the post-pandemic crisis, the numbers in our industry show a decline in 2024 compared to the previous year,” says CAPIF president Diego Zapico in the annual report shared with Billboard Español. “The causes are varied: they range from the macroeconomic reality of our country to specific factors within our sector that had been accumulating imbalances and were exposed over the past year.”

“The market decline is explained by the fact that the value of service tariffs does not keep pace with the evolution of the economy and therefore, at constant values, service prices are relatively lower today,” a representative of CAPIF tells Billboard Español. “In addition, the drop in revenues from communication to the public attributable to decree 765/24, published in the Official Gazette on August 28, 2024, which modified the intellectual property regime in Argentina, particularly with respect to the public performance of musical works, has also had an impact.”

Additionally, physical sales — though declining — still made up 7% of the market, with vinyl records solidifying their spot as collectors’ favorite format, accounting for 69% of physical sales compared to 31% for CDs.

“Our country is an endless source of talent, with an incredible diversity of styles, genres, and music,” adds Zapico. “It’s a place where creativity flows freely, where artists collaborate across boundaries, and where languages and sounds constantly mix, fuse, invent and reinvent themselves.”

The report also highlights the impact of Latin artists in the top 10 of the 2024 General Ranking. Among the most popular tracks are “Hola Perdida” by Luck Ra and KHEA, “Piel” by Tiago PZK and Ke Personajes, and “Que Me Falte Todo” by Luck Ra and Abel Pintos. Other hits, like “Una Foto” by Mesita, Nicki Nicole, Tiago PZK and Emilia, as well as “La_Original.mp3” by Emilia and Tini, showcase the reach of Argentine music in both the local and regional markets.

“This is our unique national identity when it comes to art and music, and it’s what drives the success of many of our artists around the world,” says Zapico. “From the legends and established stars to the newcomers who emerge year after year, their strong presence at the top of global and regional charts and scenes stems from this.”

Check out the full top 10 of the 2024 General Ranking below:

Luck Ra y KHEA, “Hola Perdida”

Tiago PZK y Ke Personajes, “Piel”

Luck Ra y Abel Pintos, “Que Me Falte Todo”

Feid y ATL Jacob, “Luna”

Mesita, Nicki Nicole, Tiago PZK y Emilia, “Una Foto”

Los Ángeles Azules y Emilia, “Perdonarte, ¿Para Qué?”

Emilia y Tini, “La_Original.mp3″

Floyymenor y Cris MJ, “Gata Only”

Luck Ra y BM, “La Morocha”

Salastkbron y Diego París, “Un Besito Más”

On the other hand, “Luna” by Feid and ATL Jacob leads the top 10 of the Spanish-Language Foreign Artists Repertoire; while Benson Boone leads the top 10 of the Foreign Artists Repertoire in Other Languages ranking.

To see the full annual charts, click here.

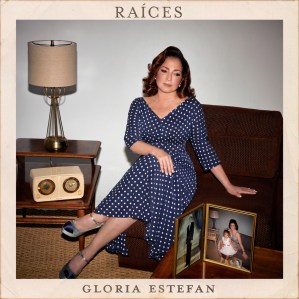

Gloria Estefan is ready to introduce the world to Raíces, her first Spanish-language album in 18 years and the 30th in her 50-year career. It is, in the words of the superstar, “like a modern Mi Tierra” — a sort of sequel to her iconic first LP in her native language, but freer.

“When we had the concept for the [1993] album Mi Tierra, we wanted to highlight a rich era of Cuban music that had been celebrated worldwide B.C. — before Castro,” the Cuban-American artist tells Billboard Español. “Back then, we were very careful to use the language that would have been used in the 1940s in the songs — the arrangements, the instrumentation, we kept it very much of that era. Here, we felt free to explore, always keeping family in mind and the music that gave us so much richness, and which helped us create these fusions, but coming from a very organic and real place.”

Set to release on Friday (May 30) under Sony Music Latin, Raíces consists of 13 tracks mostly written by musician and producer Emilio Estefan Jr., Gloria’s inseparable partner in life and career for over four decades. Salsa, bolero, and tropical rhythms resonate in songs ranging from previously released singles like “Raíces” and “La Vecina (No Sé Na’)” to deeply romantic tracks such as “Tan Iguales y Tan Diferentes,” “Te Juro,” “Agua Dulce,” and “Tú y Yo.”

Among the few songs penned by Gloria is the sweet “Mi Niño Bello (Para Sasha),” dedicated to her only grandson, with the English version “My Beautiful Boy (For Sasha).” “Since he was born, we’ve had a very beautiful and close relationship,” she proudly shares, adding that in Spanish she wanted to create something “with the flavor of ‘Drume Negrita,’ something very classic, a Cuban lullaby.”

A second song on the album, “Cuando el Tiempo Nos Castiga” (co-written by Emilio and Gian Marco and originally recorded by Jon Secada in 2001), also has a new English version courtesy of Gloria, titled “How Will You Be Remembered.” “I never translate exactly. I think about the feeling, the emotion, what one wants to express about the theme, and I approach it in the new language. In English, I was thinking more about legacy — you want to feel happy with what you left behind,” she explains about the discrepancy in the titles, with the one in Spanish meaning “When time punished us.”

Estefan — who in 2023 became the first Latina inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and in 2024 received the Legend Award at the Billboard Latin Women in Music ceremony — usually writes more for her albums, but this time she was focused on creating songs for the upcoming Broadway musical BASURA alongside her daughter Emily when Emilio presented her with the idea for the song “Raíces” a couple of years ago.

“Emilio didn’t even realize it was my 50th [career anniversary],” recalls Estefan, who wanted to do something special to celebrate the milestone. “I told him, ‘Babe, I can’t change my mindset for this, but I would like, if I do an album again, for it to be tropical, for it to be in Spanish.’ He says, ‘Do you trust me?’ I go, ‘Who else am I gonna trust than you?’”

Raíces is Gloria Estefan’s first Spanish-language album since 90 Millas, which debuted and spent three weeks at No. 1 on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart in October 2007. Mi Tierra, meanwhile, spent a whooping 58 weeks at the top of the chart.

Estefan also spoke about the new Pope Leo XIV, immigration, and more. Watch the interview in the video above.

Gloria Estefan, ‘RAICES’

Courtesy Photo

Back in 2005, Spanish star Alejandro Sanz — the heartthrob with raspy vocals, a poet’s way with words and a flamenco flair that defined his global pop sound — teamed with another superstar, Colombia’s Shakira, for “La Tortura,” a sexy flamenco/reggaetón vamp.

It was a headline-grabbing collaboration at a time when such pairings were scarce in Latin music: Spain’s most lauded and top-selling artist cavorting with a crossover star at the height of her popularity.

Accompanied by a video dripping in sensuality, featuring an oil-bathed Shakira writhing on a kitchen table, the song exploded, notching a then-record 25 weeks at No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot Latin Songs chart.

Trending on Billboard

Twenty years later, Shakira and Sanz again danced together to heightened expectations. On May 13, the Colombian star invited her Spanish buddy as a special guest to the opening date of her U.S. tour at Bank of America Stadium in Charlotte, N.C., where the two performed “La Tortura.”

The moment served as a bookend in Sanz’s career as he prepares to release ¿Y Ahora Qué?, his first studio album in four years, featuring “Bésame,” a new duet with Shakira, as the focus track. The song, which harks back to the flamenco/Caribbean sound of “La Tortura” but is set over sparse dance beats, boasts that mix of sophisticated and commercial that has informed so many Sanz hits through the years.

But ¿Y Ahora Qué?, which translates to “Now What?,” is as existential as it is hit-driven, navigating intensely personal fare with humor and unexpected turns.

“It’s what you ask yourself every time you start something new, every time you face change, when you change your sentimental life and things happen that truly move you,” Sanz says, sitting next to me on a couch on a Tuesday afternoon.

Fit, tan and still charmingly impish, Sanz met with Billboard over a glass of red wine at Sony’s 5020 Studios in Miami in early May. This kind of scenario — warm, open, unscripted — has very much been the Sanz way through the years; once he opens up, he shuns formality and careful choreography.

His first album on Sony Music Latin, Y Ahora, is an EP that follows a turbulent period where he switched labels (leaving Universal after a decade in 2021), his former manager took him to court, and, most recently, he publicly dealt with depression and a romantic breakup.

Aside from longtime friend Shakira, Sanz also collaborates with hot new hit-makers Grupo Frontera — in a salsa that steers the act far from its regional Mexican sound — and Manuel Turizo, who eschews his up-tempo rhythmic dance fare for a more melancholy ballad.

For Sanz, it’s a jump of boldness and optimism after the storm. The cover of the album shows him in various stages of movement — walking, leaping, running — as does his newly released tour art. Sanz is a prolific live artist whose 2023 shows grossed $23.8 million and sold 235,000 tickets, according to Billboard Boxscore. All told, between 2022 and 2024, his Sanz en Vivo tour (his largest to date), played 86 concerts throughout Europe, Mexico, South America and the United States, selling over 860,000 tickets and grossing $100 million, according to his management. Sanz has already announced the first leg of his new tour and is slated to play 17 dates in Mexico, including four-sold nights at Auditorio Nacional from a presale, prompting the addition of two more.

Mary Beth Koeth

But Sanz’s real strength lies in his songs. Rhythmically complex and riveting, underscored by his distinctively raspy voice, Sanz’s compositions have led to 14 career entries on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart, including four No. 1s and 11 top 10s. On Hot Latin Songs, he has notched 28 entries, including 10 top 10s and five No. 1s; he has won five Grammys and 25 Latin Grammys, and he holds the title for most wins — seven — for record of the year at the Latin Grammys.

In his native Spain, Sanz still boasts the top-selling album of all time, according to local society Promusicae: his 1997 breakthrough, Más, which has been certified 22 times platinum for 2.2 million certified copies sold, and includes his biggest, most lasting hit, “Corazón Partío.”

“In my opinion, Alejandro is the best Spanish-language composer of all time,” says Iñigo Zabala, the former head of Warner Music Latin America & Spain who signed Sanz to his first recording deal back in 1991.

Today, Zabala co-manages Sanz in an unorthodox agreement with Alex Mizrahi, with the two executives focused on different areas of his career. Mizrahi, who heads management and promotion company OCESA-Seitrack, oversees Sanz’s international management and business, while Zabala, who is also a musician, handles his recording career and creative output.

The two began managing Sanz in 2022 when the artist was at a crossroads. He had no formal manager and had decided to end his contract with Universal Music, his home since 2011. But he continued touring, and Mizrahi, his agent in Latin America, yearned to expand his relationship with him.

“I’m a manager focused on touring. But an artist as sophisticated as Sanz needs someone like Iñigo, who knows his origins and who’s had a long artistic relationship,” Mizrahi says.

That same mind frame — artistry leading the business — also informed Sanz’s decision to sign with Sony Music a year later, in a license deal that lets him keep control of his masters.

“I need a label I can talk music with, who will dream about repertoire with me,” Sanz says. “I have attorneys to talk numbers, and so do they.”

Mary Beth Koeth

Which is not to say Sanz is improvising. Beyond his touring, he has been active in ancillary, visible projects. He’s in the midst of shooting a Netflix documentary that will premiere this fall, and production crews have followed him for the past year, including when he sat for a Q&A at Billboard Latin Music Week last year and received the Billboard Lifetime Achievement Award.

His music is also being used for an upcoming stage musical, jukebox-style, that is not based on his life story, but features a character called Ale. And a deluxe version of ¿Y Ahora Qué? will be released later in 2025 with additional collaborations.

Sanz spoke to Billboard about his creative process and where he is now.

So, now what?

“Now what,” “¿Y ahora qué?,” is the first line of the album, in [the single] “Palmeras en el Jardín.” “Now what?” is a question almost everyone asks themselves at some point. Whenever you’re about to start something new, whenever something happens, whenever you face a change, you ask yourself, “Now what?” Especially when it comes to emotional or sentimental changes that really shake you up. I find it very relatable, and I love taking common phrases or ideas that are already part of our collective imagination and giving them a poetic twist in my albums.

“Palmeras en el Jardín,” the song with that phrase and the first single, is about sadness and the loss of your previous relationship. But the album’s mood shifts after that.

I think emotions don’t really distinguish between what’s sad and what’s happy; instead, they create a certain sense of satisfaction. You like sunny days, but sometimes you also enjoy rainy ones, don’t you? “Palmeras en el Jardín” is the rainy day, and there are a few sunny ones throughout the album. It felt fitting for that to be the first thing said because it reflects the inner struggle I went through to start making this album and to feel inspired again to create new songs. I needed that question in my life: “Now what?” Because you have so many options — stay where you are, crumble, move forward, climb higher or jump out of a hot air balloon.

Do you have a process for starting to make music, or do you just wait for the perfect moment?

No, no. Waiting for the perfect moment is just laziness and shows zero commitment. I think you have to actively go after the song, just like you chase luck or love.

Are you disciplined when it comes to songwriting?

When I have to do it, I do it. When I first started making albums, I could write anywhere — in a bakery or on a plane. Now I go to the studio and work with the people I collaborate with — musicians, producers, composers — and approach it differently. Before, I used to lock myself in my room and spend 14 hours writing compulsively and, honestly, in a completely unhealthy way. But that’s how I used to do it. Now I find shorter sessions much more productive, and I’ve changed the way I work.

I used to think those habits were set in stone…

But they’re not. You can change them. The same tools from before don’t always work anymore. For example, when I used to write an album, I would always learn a new instrument or find inspiration within the music itself. Now I’ve discovered that working with other people really sparks something in me. It teaches me a lot, and I get to share what I know, too. That fascinates me because I’d never done it before.

Speaking of working with others, this album has a lot of collaborations. You’ve got three, including “Bésame” with Shakira. How did that one happen?

We’d been talking for a while about working together again. I used to joke with her, saying, “When are we going to make another song? You only make songs with talented, handsome guys!” We hadn’t found the right song that we both connected with. It’s tough after making a song like “La Tortura” to find the right reason to team up again. You don’t want to be too predictable or repeat the same thing, but you also want the new collaboration to be just as sweet.

You’re both so busy. Did you work together in the studio?

No, we didn’t. But I think the process unfolded exactly how it needed to. We worked perfectly by sending ideas back and forth. We’d send each other voice notes and messages. We’re both very hands-on artists, so our conversations were intense. She’d send me audiobooks, and I’d try to summarize them. It was beautiful because we managed to create what we always do when we sing together: Something magical happens. I think we accomplished that by combining our roots, a little imagination and, now, some added experience. There weren’t any arguments because she loves the world of flamenco and we really admire each other’s work. That mutual respect is so important when collaborating.

This album feels like a release for you — more so than others.

Well, what is a release, really? At its core, why do we use music? To communicate. Over time, music has become more commercialized, but if you think about it, the original reason for making songs was to tell your stories and free yourself. People are always surprised when music is used to tell deeply personal stories, but that’s how it’s always been. The difference now is that, with social media, everyone knows exactly where the stories are coming from. I often debate whether to release something or not. But what’s the alternative? Once everything is out in the open and the well is discovered, it’s there for everyone. You can’t clip the wings of creativity just because you feel a little embarrassed about one feather.

When people ask me if this album has a common thread, I say that the connection is me — my voice, my way of interpreting music. I’ve always loved being eclectic and exploring different rhythms. That’s the beauty of music — it reflects what’s happening in your life.

“Hoy No Me Siento Bien” with Grupo Firme is a salsa song, despite its title, and it’s upbeat. But “Como Sería” with Manuel Turizo and “Vino de Tu Boca” are about loss.

“Hoy No Me Siento Bien” is about recognizing that it’s OK to feel bad sometimes. It’s about finding the light at the end of a dark tunnel. That’s why the synergy between the lyrics, which talk about emotional struggles, and the upbeat music works — it’s like saying, “I feel bad, but it’s OK.”

You and Shakira are aligned, but it feels like you pushed Turizo and Grupo Frontera out of their comfort zones. Did Frontera ever say no to singing salsa?

No, not at all. They were excited! I think they love experimenting with music, and you can tell. What musician doesn’t enjoy playing around with music, trying new things and getting their hands dirty? That’s the most wonderful part of doing this job.

Let’s talk about “Como Sería,” your ballad with Turizo.

It’s a ballad, but not your typical ballad. It has layers and corners that feel familiar for a ballad, but it’s less safe. You know, there are ways to write lyrics or melodies that keep you in your comfort zone, but this song steps out of it. I hadn’t worked with Manuel before, but we met at a show in Spain, hit it off and decided to make a song together. His brother also co-wrote it, and honestly, the result is great. It’s similar to the single with Shakira — there’s a bit of his world, a bit of mine, and we meet in a place where you wouldn’t expect to see either of us.

Did you write it together?

They had an idea and sent it to me, and we went back and forth. Some might think that process sounds cold, but I love it. Sometimes when you’re in the same room writing, there are distractions — other people watching who aren’t contributing, for example. When you’re in the studio, there’s embarrassment or hesitation, and it doesn’t flow the same way. But when someone sends you the song, you’re at home, tweaking it, sending it back — you have the intimacy to work freely.

I love this album. It feels like it has all the right songs. What does this album mean to you?

It came into my life at a very important moment. I was closing a chapter where, musically and emotionally, I was in a tough spot. I was caught up in conversations that had nothing to do with music — more about numbers and other things that didn’t resonate with me. I got into music to free myself from math equations, to wake up late and to be my own boss — those are the three things I’ve always wanted to be. Somewhere along the way, I lost that excitement. Before, people would sell out musically, but they’d do it discreetly. Now it’s out in the open: “Let’s make this trash because we know it’ll work.” And if you don’t do that, you get stuck in this giant drawer of [old artists]. I was in that space, and this album brought light back into my life — into that empty space where my passion, drive and effort had disappeared.

Mary Beth Koeth

With today’s business models, I keep hearing that artists need to manage their businesses themselves.

A lot of artists love to say they’re entrepreneurs and that’s fine, but I don’t believe it. As an artist, you can try to make a living however you want based on supply and demand, but I don’t think you can truly be an entrepreneur at the same time. There’s a complete conflict of interest there.

Beyond the music, you’ve spoken openly about your experiences with depression and mental health in 2023. Why?

Because it’s important. If not us, then who? If we can’t openly talk about these things, then what are we showing the people listening to this interview, for example? That they should be ashamed of it? No. But it’s a very personal thing.

Did it take you a while to decide to say, “I’m feeling bad, but I’m going to talk about it”? I ask especially because you’re so private.

Yes, I’m very private about the things that aren’t anyone else’s business because, really, no one cares about what I do in my personal life. But this is something that affects everyone, and I think it’s good to talk about it. When I was going through it, I struggled with social situations. Seeing too many people at once gave me anxiety. But the one place I felt comfortable was onstage.

You’d think it would be the opposite.

Exactly. I did my first concert in Spain and thought, “If this goes well, I’ll do the tour. If not, I won’t.” And I felt amazing up there. As the tour went on, I made changes to prioritize myself. For example, I decided not to meet with anyone after the show. I’d finish the concert, go to my hotel or my house and not worry about meeting everyone’s expectations. That’s so important — to be polite, do your job well, be kind to your people and that’s it. That’s all you need to demand of yourself. The rest should be whatever makes you happy. If signing autographs for 20 hours makes you happy, do it. But if it doesn’t, then don’t.

Do you have mechanisms to manage your anxiety?

It’s less about mechanisms and more about habits. I’ve learned to say no. You always try to be the person you once were — to be nice to everyone. But I know how to set boundaries now, and I don’t let things get out of hand.

What can we expect from this tour?

I’m really excited to include new songs in the setlist. I want to invite friends to some of the shows, but mostly, I want to completely refresh the repertoire. I don’t know if I’ll perform the entire album, but almost all of it. There will also be changes within the band. We start rehearsals in July and will spend all of July and about 20 days in August rehearsing in Spain at my place in the country. I set up a tent there, and we rehearse surrounded by horses, sheep and chickens. I want to create something beautiful and put a lot of care into the stage design. There’s always a special connection during the concerts. We always create something unique, and it’s been a while since we’ve seen each other.

Back in 2005, Spanish star Alejandro Sanz — the heartthrob with raspy vocals, a poet’s way with words and a flamenco flair that defined his global pop sound — teamed with another superstar, Colombia’s Shakira, for “La Tortura,” a sexy flamenco/reggaetón vamp. It was a headline-grabbing collaboration at a time when such pairings were scarce […]

Los Tigres del Norte have enjoyed a career spanning over 57 years. The renowned regional Mexican group sat down with Leila Cobo to share their thoughts on some of their biggest hits, including “Contrabando y Traición.” They also discussed their thought process behind their new track, “La Lotería,” their decision to include an image of Donald Trump as “el diablito,” their opinions on narcocorridos and the ongoing efforts to ban them, immigration issues in the U.S.. and more.

What do you think of the “La Lotería” music video? Let us know in the comments!

Leila Cobo:

Los Tigres del Norte, welcome to Miami.

Los Tigres del Norte:

Thank you.

It’s so great to have you, like always, I always have to go to other places to find you, but today you guys came to the tropics. On top of that, I really appreciate you guys being dressed up like Miami.

Thank you so much.

Apart from that fact that we’re at a Mexican restaurant-

We’re here at our Mexican restaurant.

At Tacology.

It’s so pretty.

Yes, very pretty. I only take you guys to pretty places.

Everytime you invite us, you always take us to wonderful places.

How many years has it been?

We have many years under our belt. We have recorded-

40?

CDs since 1968.

1968?

Many years already. I think that the first song that people knew us by was “Camelia, la Texana.”

It’s one of the corridos that got people to notice Los Tigres del Norte. It’s already been many years.

Well, Jorge told me the story about “Camelia, la Texana.” I’m trying to remember, but weren’t you under age when you recorded that song?

Practically.

And you were there hiding yourself in bars to sing it no?

Exactly, I told you the story of how the song was born because they brought me to a place in Los Angeles because I was underage and the didn’t let me enter the place.

Keep watching for more!

Go behind the scenes with Leila Cobo at Latin Music Week 2024 as she finds out if Peso Pluma cooks, rides with Grupo Frontera to see how they warm up before a show, offers advice to Thalía, takes a shot with Tito Double P’s team, and more!

Peso Pluma:

Anyway, I live here. If he tells me, “I’ll go home tomorrow,” I’ll invite you to eat soup the day that you want.

Leila Cobo:

Seriously? Are you going to prepare the soup?

Peso Pluma:

No, we have the Mexican chef.

Thalia:

This girl told us to come to the panel, and then she said, “What are you going to do?” What!

Leila Cobo:

Did they tell you the dress code?

Alejandro Sanz:

Yes, of course.

Leila Cobo:

Didn’t they tell you it was a tuxedo and…

Alejandro Sanz:

I had to come like this. You know what I wear.

Leila Cobo:

You wanted to bring me a purse? You didn’t have to.

J Balvin:

I always do that with women.

Leila Cobo:

Thank you.

Ronald Day:

Where should it say Latin Week?

Leila Cobo:

Here, Latin Power Players. Hey!

Leila Cobo:

I am looking for air.

Leila Cobo:

Isa, can you interview Ronald? Because Ronald is the President of Telemundo.

Isabela Raygoza:

Really?

Leila Cobo:

So he’s going to do our show.

Leila Cobo:

He’s the man. Telemundo in the house.

Emilio Estefan:

Oh, yea.

Leila Cobo:

A kiss in the air so we don’t lose our makeup.

Emilio Estefan:

I went off air where I was working and now…

Leila Cobo:

I love it! Really?

Emilio Estefan:

For you? Anything for you.

Keep watching for more!

Shakira has added more dates to her Mexican residency as part of her “Mujeres Ya No Lloran” World Tour and the Colombian singer shares what she loves about her Mexican fans, performing with Grupo Frontera and more! Have you attended her concert? Let us know in the comments! Natalia Cano: Shakira, well, it’s been a […]

For the first time during her Las Mujeres Ya No Lloran World Tour, Shakira shared the stage with special guests. On Tuesday (March 25), during her fourth night at the iconic GNP Seguros Stadium in Mexico City, the Colombian superstar was joined by Grupo Frontera for a live performance of “(Entre Paréntesis),” a song from her 2024 album that gives its name to the tour.

“I really wanted to give you all a surprise,” Shakira told Billboard Español in an interview following the show. “Every day, I strive to give you something more because the Mexican audience has been so loyal, so loving, and has lifted me up every time I needed it. I wanted to surprise you with something that would fill your hearts. Having them on stage today was a true privilege.”

“(Entre Paréntesis)” joins “Ciega, Sordomuda” and “El Jefe” as songs Shakira has added to her extensive repertoire as a heartfelt tribute to Mexico, where she continues her historic seven-night residency at the GNP Seguros Stadium (formerly known as Foro Sol), which will conclude on Sunday (March 30). This milestone makes her the first female artist to perform this many shows at the venue, previously filled by artists like Paul McCartney, Taylor Swift, Coldplay and Metallica. In total, the residency will gather 455,000 attendees, according to promoter OCESA.

Trending on Billboard

But Grupo Frontera wasn’t the only guest of the night: Lili Melgar, nanny to Shakira’s sons Milan and Sasha, made a surprise appearance while the singer performed “El Jefe,” her collaboration with Fuerza Regida, in which Melgar is immortalized in one of the final verses. “Lili Melgar, this song is for you, for not being paid your severance,” Shakira shouted to the thunderous roar of her Mexican pack, undeterred by the rain during their reunion with the She Wolf.

Still emotional from the warm reception from her Mexico audience, the 48-year-old star revealed that there will be more surprises for the U.S. leg of the Las Mujeres Ya No Lloran trek, which kicks off May 13 in Charlotte, North Carolina.

“For the first part of the tour, I wanted the show to stay as it was, for the fans to experience the songs just as I conceived them,” she told Billboard Español. “But now I’ll be incorporating some surprises and special guests that you’ll see in the United States. It will be very exciting to share the stage with friends and colleagues.”

One year after the release of Las Mujeres Ya No Lloran — the Grammy-winning album that marked her triumphant first album in seven years — Shakira reflected on what this project has meant to her. The set reached No. 1 on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart and No. 13 on the all-genre Billboard 200. Last Friday (March 21), the Colombian singer premiered the video for “Última,” her latest single from the album, filmed in the New York City subway and directed by close friend and photographer Jaume de Laiguana.

“I believe this has been a healing process for me and for many people — not just women, men too. I think together we’ve learned that you grow from setbacks, and that together we heal when we support each other,” she said. “That’s what the audience has done for me. They’ve given me strength when I felt weak, and I know I’ve done the same for them.”

On her historic current stadium tour — which began on Feb. 11 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and will still visit the Dominican Republic, Chile and Colombia before arriving in the U.S.— Shakira says that this series of shows has become something deeper and more intimate.

“These are more than just concerts. They’re very profound gatherings where healing happens,” she stated. “With each show, I feel stronger and happier.”

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio