artificial intelligence

Page: 7

As artificial intelligence continues to blur the lines of creativity in music, South Korea’s largest music copyright organization, KOMCA (Korea Music Copyright Association), is drawing a hard line: No AI-created compositions will be accepted for registration. The controversial decision took effect on March 24, sending ripples through Korea’s music scene and sparking broader conversations about AI’s role in global songwriting.

In an official statement on its website, KOMCA explained that due to the lack of legal frameworks and clear management guidelines for AI-generated content, it will suspend the registration of any works involving AI in the creative process. This includes any track where AI was used — even in part — to compose, write lyrics or contribute melodically.

Now, every new registration must be accompanied by an explicit self-declaration confirming that no AI was involved at any stage of the song’s creation. This declaration is made by checking a box on the required registration form — a step that carries significant legal and financial consequences if false information is declared. False declarations could lead to delayed royalty payments, complete removal of songs from the registry, and even civil or criminal liability.

Trending on Billboard

“KOMCA only recognizes songs that are wholly the result of human creativity,” the association said, noting that even a 1% contribution from AI makes a song ineligible for registration. “Until there is clear legislation or regulatory guidance, this is a precautionary administrative policy.”

The non-profit organization represents over 30,000 members, including songwriters, lyricists, and publishers, and oversees copyright for more than 3.7 million works from artists like PSY, BTS, EXO and Super Junior.

Importantly, the policy applies to the composition and lyric-writing stages of song creation, not necessarily the production or recording phase. That means high-profile K-pop companies like HYBE, which have used AI to generate multilingual vocal lines for existing songs, are not directly affected — at least not yet.

While South Korea’s government policy allows for partial copyright protection when human creativity is involved, KOMCA’s stance is notably stricter, requiring a total absence of AI involvement for a song to be protected.

This move comes amid growing international debate over the copyrightability of AI-generated art. In the U.S., a federal appeals court recently upheld a lower court’s decision to reject copyright registration for a work created entirely by an AI system called Creativity Machine. The U.S. Copyright Office maintains that only works with “human authorship” are eligible for protection, though it allows for copyright in cases where AI is used as a tool under human direction.

“Allowing copyright for machine-determined creative elements could undermine the constitutional purpose of copyright law,” U.S. Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter said.

With AI tools becoming increasingly sophisticated — and accessible — KOMCA’s policy underscores a growing tension within the global music industry: Where do we draw the line between assistance and authorship?

This article originally appeared on Billboard Korea.

HYBE is continuing to work to protect its artists. Korea’s Northern Gyeonggi Provincial Police Agency (NGPPA) worked with the global entertainment company to arrest eight individuals who are suspected of creating and distributing deepfake videos of HYBE Music Group artists, Billboard can confirm. Deepfakes are false images, videos or audio that have been edited or generated using […]

HYBE Interactive Media (HYBE IM) secured an additional KRW 30 billion ($21 million) investment, with existing investor IMM Investment contributing another KRW 15 billion ($10 million) in follow-on funding. Shinhan Venture Investment and Daesung Private Equity joined as new investors in the company, which plans to expand its game business using HYBE’s K-pop artist IPs. To date, HYBE IM has raised a total of KRW 137.5 billion ($100 million). With the new money, the company plans to enhance its publishing capabilities and execute its long-term growth strategy by allocating it to marketing, operations and localization strategies to support the launch of its gaming titles.

Live Nation acquired a stake in 356 Entertainment Group, a leading promoter in Malta’s festival and outdoor concert scene that operates the country’s largest club, Uno, which hosts more than 100 events a year. The two companies have a longstanding partnership that has resulted in events including Take That’s The Greatest Weekend Malta and Liam Gallagher and Friends Malta Weekender being held in the island country. According to a press release, 356’s festival season brought 56,000 visitors to the island, generating an economic impact of 51.8 million euros ($56.1 million). Live Nation is looking to build on that success by bringing more diverse international acts to the market.

Trending on Billboard

ATC Group acquired a majority stake in indie management company, record label and PR firm Easy Life Entertainment. The company’s management roster includes Bury Tomorrow, SOTA, Bears in Trees, Lexie Carroll, Mouth Culture and Anaïs; while its label roster boasts Lower Than Atlantis, Tonight Alive, Softcult, Normandie, Amber Run, Bryde and Lonely The Brave. Its PR arm has worked on campaigns for All Time Low, 41, Deaf Havana, Neck Deep, Simple Plan, Travie McCoy and Tool.

Triple 8 Management partnered with Sureel, which provides AI attribution, detection, protection and monetization for artists. Through the deal, Triple 8 artists including Drew Holcomb & the Neighbors, Local Natives, JOHNNYSWIM, Mat Kearney and Charlotte Sands will have access to tools that allow them to opt-in or opt-out of AI training with custom thresholds; protect their artist styles from being used in AI training without consent by setting time-and-date stamp behind ownership; monetize themselves in the AI ecosystem through ethical licensing that can generate revenue for them; and access real-time reporting through Sureel’s AI dashboard. Sureel makes this possible by providing AI companies “with easy-to-integrate tools to ensure responsible AI that fully respects artist preferences,” according to a press release.

Merlin signed a licensing deal with Coda Music, a new social/streaming platform that “is reimagining streaming as an interactive, artist-led experience, where fans discover music through community-driven recommendations, discussions, and exclusive content” while allowing artists “to cultivate more meaningful relationships with their audiences,” according to a press release. Through the deal, Merlin’s global membership will have access to Coda Music’s suite of social and discovery-driven features, allowing artists to engage with fan communities by sharing exclusive content and more. Users can also follow artists and fellow fans on the platform and exchange music recommendations with them.

AEG Presents struck a partnership with The Boston Beer Company that will bring the beverage maker’s portfolio of brands — including Sun Cruiser Iced Tea & Vodka, Truly Hard Seltzer, Twisted Tea Hard Iced Tea and Angry Orchard Hard Cider — to nearly 30 AEG Presents venues nationwide including Brooklyn Steel in New York, Resorts World Theatre in Las Vegas and Roadrunner in Boston, as well as festivals including Electric Forest in Rothbury, Mich., and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival.

Armada Music struck a deal with Peloton to bring an exclusive lineup of six live DJ-led classes featuring Armada artists to Peloton studios in both New York and London this year. Artists taking part include ARTY and Armin van Buuren.

Venu Holding Corporation acquired the Celebrity Lanes bowling alley in the Denver suburb of Centennial, Colo., for an undisclosed amount. It will transform the business into an indoor music hall, private rental space and restaurant.

Secretly Distribution renewed its partnership with Sufjan Stevens‘ Asthmatic Kitty Records, which has released works by Angelo De Augustine, My Brightest Diamond, Helado Negro, Linda Perhacs, Lily & Madeleine, Denison Witmer and others. Secretly will continue handling physical and digital music distribution, digital and retail marketing, and technological support for all Asthmatic Kitty releases.

Symphonic Distribution partnered with digital marketing platform SymphonyOS in a deal that will give Symphonic users discounted access to SymphonyOS via Symphonic’s client offerings page. Through SymphonyOS, artists can launch and manage targeted ad campaigns on Meta, TikTok and Google; access personalized analytics for a full view of fan interactions across platforms; build tailored pre-save links, link-in-bio pages and tour info pages; and get AI-powered real time recommendations to improve marketing campaigns.

Bootleg.live, a platform that turns high-quality concert audio into merch, partnered with Evan Honer and Judah & the Lion to offer fans unique audio collectibles on tour. Both acts are on tour this fall. The collectibles, called “bootlegs,” are concert recordings taken directly from the board, enhanced using Bootleg’s proprietary process, and combined with photos and short videos.

The NO FAKES Act was reintroduced to the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate on Wednesday (April 9) with the help of country legend Randy Travis, his wife Mary Travis and Warner Music Group CEO Robert Kyncl.

The reintroduction of the bill, designed to protect artists against unauthorized AI deepfake impersonations, was part of the Recording Academy’s annual GRAMMYs on the Hill initiative, in which the organization visits D.C. to meet with elected officials and advocate for a variety of music-related causes. On Wednesday, the GRAMMYs on the Hill Awards celebrated Travis, along with U.S. Representatives Linda Sánchez (D-CA) and Ron Estes (R-KS), for their dedication and advocacy for the rights of music creators.

Introduced by Senators Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Chris Coons (D-DE), Thom Tillis (R-NC) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Representatives María Elvira Salazar (R-FL-27), Madeleine Dean (D-PA-4) Nathaniel Moran (R-TX-1), Becca Balint (D-VT-At Large), the NO FAKES Act has also found new supporters in an unlikely place: the tech industry. The bill is now supported by tech giants like YouTube, OpenAI, IBM and Adobe, showing a rare moment of solidarity between artists and big tech in the AI age.

Trending on Billboard

The NO FAKES Act was first introduced as a draft bill in 2023, and formally introduced to the Senate in the summer of 2024. If passed, the legislation would create federal intellectual property protections for the so-called right of publicity for the first time, which adds restrictions to how someone’s name, image, likeness and voice can be used without consent. Currently, these rights are only protected at the state level, leading to a patchwork of varying laws around the nation.

Unlike some of the patchy state publicity rights laws, the federal right that the NO FAKES Act would create would not expire at death and could be controlled by a person’s heirs for 70 years after their passing. There are, however, specific carve outs for replicas used in news, parody, historical works and criticism to ensure the First Amendment right to free speech remains protected.

Over the last few years, as AI voice models have continued to develop, many artists have often found themselves on the receiving end of AI deepfakes. In 2023, the AI music craze kicked off with the so-called “fake Drake” song “Heart On My Sleeve” which featured the unauthorized AI voices of Drake and the Weeknd. Last year, Taylor Swift, for example, was the subject of a number of sexually-explicit AI deepfakes of her body; the late Tupac Shakur‘s voice was deepfaked by fellow rapper Drake in his Kendrick Lamar diss track “Taylor Made Freestyle,” which was posted, and then deleted, on social media.

Even President Donald Trump participated in the deepfake trend, posting an unauthorized AI image of Swift allegedly endorsing him during his campaign to return to the White House.

“Recently, I was made aware that [an] AI [image] of ‘me’ falsely endorsing Donald Trump’s presidential run was posted to his site. It really conjured up my fears around AI, and the dangers of spreading misinformation,” Swift wrote in an Instagram post soon after. “It brought me to the conclusion that I need to be very transparent about my actual plans for this election as a voter. The simplest way to combat misinformation is with the truth.”

Overall, the bill has seen widespread support among the entertainment industry establishment. According to a press release about the bill’s reintroduction, it is celebrated by Sony Music, Warner Music Group, Universal Music Group, the Recording Industry Association of America, the Recording Academy, SAG-AFTRA, Human Artistry Campaign, Motion Picture Association and more.

Mitch Glazier, chairman and CEO of the RIAA, praised the bipartisan effort, saying “this bill proves that we can prioritize the growth of AI and protecting American creativity at the same time.”

Harvey Mason jr., CEO of the Recording Academy, added: “The Academy is proud to represent and serve creators, and for decades, GRAMMYs on the Hill has brought music makers to our nation’s capital to elevate the policy issues affecting our industry. Today’s reintroduction of the NO FAKES Act underscores our members’ commitment to advocating for the music community, and as we enter a new era of technology, we must create guardrails around AI and ensure it enhances – not replaces – human creativity.”

Generative AI — the creation of compositions from nothing in seconds — isn’t disrupting music licensing; it’s accelerating the economic impact of a system that was never built to last. Here’s the sick reality: If a generative AI company wanted to ethically license Travis Scott’s “Sicko Mode” to train their models, they’d need approvals from more than 30 rights holders, with that number doubling based on rights resold or reassigned after the track’s release. Finding and engaging with all of those parties? Good luck. No unified music database exists to identify rights holders, and even if it did, outdated information, unanswered emails, and, in some cases, deceased rights holders or a group potentially involved in a rap beef make the process a nonstarter.

The music licensing system, or lack thereof, is so fragmented that most AI companies don’t even try. They steal first and deal with lawsuits later. Clearing “Sicko Mode” isn’t just difficult; it’s impossible — a cold example of the complexity of licensing commercial music for AI training that seems left out of most debates surrounding ethical approaches.

Trending on Billboard

For those outside the music business, it’s easy to assume that licensing a song is as simple as getting permission from the artist. But in reality, every track is a tangled web of rights, split across songwriters, producers, publishers and administrators, each with their own deals, disputes and gatekeepers. Now multiply the chaos of clearing one track by the millions of tracks needed for an AI training set, and you’ll quickly see why licensing commercial music for AI at scale is a fool’s errand today.

Generative AI is exposing and accelerating the weaknesses in the traditional music revenue model by flooding the market with more music, driving down licensing fees and further complicating ownership rights. As brands and content creators turn to AI-generated compositions, demand for traditional catalogs will decline, impacting synch and licensing revenues once projected to grow over the next decade.

Hard truths don’t wait for permission. The entrance of generative AI has exposed the broken system of copyright management and its outdated black-box monetization methods.

The latest RIAA report shows that while U.S. paid subscriptions have crossed 100 million and revenue hit a record $17.7 billion in 2024, streaming growth has nearly halved — from 8.1% in 2023 to just 3.6% in 2024. The market is plateauing, and the question isn’t if the industry needs a new revenue driver — it’s where that growth will come from. Generative AI is that next wave. If architected ethically, it won’t just create new technological innovation in music; it will create revenue.

Ironically, the very thing being painted as an existential threat to the industry may be the thing capable of saving it. AI is reshaping music faster than anyone expected, yet its ethical foundation remains unwritten. So we need to move fast.

A Change is Gonna Come: Why Music Needs Ethical AI as a Catalyst for Monetization

Let’s start by stopping. Generative AI isn’t our villain. It’s not here to replace artistry. It’s a creative partner, a collaborator, a tool that lets musicians work faster, dream bigger and push boundaries in ways we’ve never seen before. While some still doubt AI’s potential because today’s ethically trained outputs may sound like they’re in their infancy, let me be clear: It’s evolving fast. What feels novel now will be industry-standard tomorrow.

Our problem is, and always has been, a lack of transparency. Many AI platforms have trained on commercial catalogs without permission (first they lied about it, then they came clean), extracting value without compensation. “Sicko Mode” very likely included. That behavior isn’t just unethical; it’s economically destructive, devaluing catalogs as imitation tracks saturate the market while the underlying copyrights earn nothing.

If we’re crying about market flooding right now, we’re missing the point. Because what if rights holders and artists participated in those tracks? Energy needs to go into rethinking how music is valued and monetized across licensing, ad tech and digital distribution. Ethical AI frameworks can ensure proper attribution, dynamic pricing and serious revenue generation for rights holders.

Jen, the ethically-trained generative AI music platform I co-founded, has already set a precedent by training exclusively on 100% licensed music, proving that responsible AI isn’t an abstract concept, it’s a choice. I just avoided Travis’ catalog due to its licensing complexities. Because time is of the essence. We are entering an era of co-creation, where technology can enhance artistry and create new revenue opportunities rather than replace them. Music isn’t just an asset; it’s a cultural force. And it must be treated as such.

Come Together: Why Opt-In is the Only Path Forward and Opt-Out Doesn’t Work

There’s a growing push for AI platforms to adopt opt-out mechanisms, where rights holders must proactively remove their work from AI training datasets. At first glance, this might seem like a fair compromise. In reality, it’s a logistical nightmare destined to fail.

A recent incident in the U.K. highlights these challenges: over 1,000 musicians, including Kate Bush and Damon Albarn, released a silent album titled “Is This What We Want?” to protest proposed changes to copyright laws that would allow AI companies to use artists’ work without explicit permission. This collective action underscores the creative community’s concerns about the impracticality and potential exploitation inherent in opt-out systems.

For opt-out to work, platforms would need to maintain up-to-date global databases tracking every artist, writer, and producer’s opt-out status or rely on a third party to do so. Neither approach is scalable, enforceable, or backed by a viable business model. No third party is incentivized to take on this responsibility. Full stop.

Music, up until now, has been created predominantly by humans, and human dynamics are inherently complex. Consider a band that breaks up — one member might refuse to opt out purely to spite another, preventing consensus on the use of a shared track. Even if opt-out were technically feasible, interpersonal conflicts would create chaos. This is an often overlooked but critical flaw in the system.

Beyond that, opt-out shifts the burden onto artists, forcing them to police AI models instead of making music. This approach doesn’t close a loophole — it widens it. AI companies will scrape music first and deal with removals later, all while benefiting from the data they’ve already extracted. By the time an artist realizes their work was used, it’s too late. The damage is done.

This is why opt-in is the only viable future for ethical AI. The burden should be on AI companies to prove they have permission before using music — not on artists to chase down every violation. Right now, the system has creators in a headlock.

Speaking of, I want to point out another example of entrepreneurs fighting for and building solutions. Perhaps she’s fighting because she’s an artist herself and deeply knows how the wrong choices affect her livelihood. Grammy-winning and Billboard Hot 100-charting artist, producer and music-tech pioneer Imogen Heap has spent over a decade tackling the industry’s toughest challenges. Her non-profit platform, Auracles, is a much-needed missing data layer for music that enables music makers to create a digital ID that holds their rights information and can grant permissions for approved uses of their works — including for generative AI training or product innovation. We need to support these types of solutions. And stop condoning the camps that feel that stealing music is fair game.

Opt-in isn’t just possible, it’s absolutely necessary. By building systems rooted in transparency, fairness and collaboration, we can forge a future where AI and music thrive together, driven by creativity and respect.

The challenge here isn’t in building better AI models — it’s designing the right licensing frameworks from the start. Ethical training isn’t a checkbox; it’s a foundational choice. Crafting these frameworks is an art in itself, just like the music we’re protecting.

Transparent licensing frameworks and artist-first models aren’t just solutions; they’re the guardrails preventing another industry freefall. We’ve seen it before — Napster, TikTok (yes, I know you’re tired of hearing these examples) — where innovation outpaced infrastructure, exposing the cracks in old systems. This time, we have a shot at doing it right. Get it right, and our revenue rises. Get it wrong and… [enter your prompt here].

Shara Senderoff is a well-respected serial entrepreneur and venture capitalist pioneering the future of music creation and monetization through ethically trained generative AI as Co-Founder & CEO of Jen. Senderoff is an industry thought leader with an unwavering commitment to artists and their rights.

JD Vance is certainly getting things done. In the middle of February, the vice president went to Munich to tell Europeans to stop isolating far-right parties, just after speaking at the Paris AI Action Summit, where he warned against strict government regulation. Talk about not knowing an audience: It would be hard to offend more Europeans in less time without kvetching about their vacation time.

This week, my colleague Kristin Robinson wrote a very smart column about what Vance’s — and presumably the Trump administration’s — reluctance to regulate AI might mean for copyright law in the U.S. Both copyright and AI are global issues, of course, so it’s worth noting that efforts by Silicon Valley to keep the Internet unregulated — not only in terms of copyright, but also in terms of privacy and competition law — often run aground in Europe. Vance, like Elon Musk, may simply resent that U.S. technology companies have to follow European laws when they do business there. If he wants to change that dynamic, though, he needs to start by assuring Europeans that the U.S. can regulate its own businesses — not tell them outright that it doesn’t want to do so.

Silicon Valley sees technology as an irresistible force but lawmakers in Brussels, who see privacy and authors’ rights as fundamental to society, have proven to be an immovable object. (Like Nate Dogg and Warren G, they have to regulate.) When they collide, as they have every few years for the past quarter-century, they release massive amounts of energy, in the form of absurd overstatements, and then each give a little ground. (Remember all the claims about how the European data-protection regulation would complicate the Web, or how the 2019 copyright directive would “break the internet?” Turns out it works fine.) In the end, these EU laws often become default global regulations, because it’s easier to run platforms the same way everywhere. And while all of them are pretty complicated, they tend to work reasonably well.

Trending on Billboard

Like many politicians, Vance seems to see the development of AI as a race that one side can somehow win, to its sole benefit. Maybe. On a consumer level, though, online technology tends to emerge gradually and spread globally, and the winners are often companies that use their other products to become default standards. (The losers are often companies that employ more people and pay more taxes, which in politics isn’t so great.) Let’s face it: The best search engine is often the one on your phone; the best map system is whatever’s best integrated into the device you’re using. To the extent that policymakers see this as a race, does winning mean simply developing the best AI, even if it ends up turning into AM or Skynet? Or does winning mean developing AI technology that can create jobs as well as destroy them?

Much of this debate goes far beyond the scope of copyright — let alone the music business — and it’s humbling to consider the prospect of creating rules for something that’s smarter than humans. That’s an important distinction. While developing AI technology before other countries may be a national security issue that justifies a moon-shot urgency, that has nothing to do with allowing software to ingest Blue Öyster Cult songs without a license. Software algorithms are already creating works of art, and they will inevitably continue to do so. But let’s not relax copyright law out of a fear of needing to stay ahead of the Chinese.

Vance didn’t specifically mention copyright — the closest he got to the subject of content was saying “we feel strongly that AI must remain free from ideological bias.” But he did criticize European privacy regulations, which he said require “paying endless legal compliance costs or otherwise risking massive fines.” If there’s another way to protect individual privacy online, though, he didn’t mention it. For that matter, it’s hard to imagine a way to ensure AI remains free from bias without some kind of regulatory regime. Can Congress write and pass a fair and reasonable law to do that? Or will this depend on the same Europeans that Vance just made fun of?

That brings us back to copyright. In the Anglo-American world, including the U.S., copyright is essentially a commercial right, akin to a property right protected by statute. That right, like most, has some exceptions, most relevant fair use. The equivalent under the French civil law tradition is authors’ rights — droit d’auteur — which is more of a fundamental right. (I’m vastly oversimplifying this.) So what seems in the U.S. to be a debate about property rights is in most of the EU more of an issue of human rights. Governments have no choice but to protect them.

There’s going to be a similar debate about privacy. AI algorithms may soon be able to identify and find or deduce information about individuals that they would not choose to share. In some cases, such as security, this might be a good thing. In most, however, it has the potential to be awful: It’s one thing to use AI and databases to identify criminals, quite another to find people who might practice a certain religion or want to buy jeans. The U.S. may not have a problem with that, if people are out in public, but European countries will. As with Napster so many years ago, the relatively small music business could offer an advance look at what will become very important issues.

Inevitably, with the Trump administration, everything comes down to winning — more specifically getting the better end of the deal. At some point, AI will become just another commercial issue, and U.S. companies will only have access to foreign markets if they comply with the laws there. Vance wants to loosen them, which is fair enough. But this won’t help the U.S. — just one particular business in it. And Europeans will push back — as they should.

Last month, Vice President J.D. Vance represented the U.S. at the Artificial Intelligence Action Summit in Paris. In a speech addressing top leaders from around the world, he declared, “I think our response [to AI] is to be too self-conscious, too risk-averse, but never have I encountered a breakthrough in tech that so clearly calls us to do precisely the opposite. […] We believe excessive regulation of the AI sector could kill a transformative industry just as it’s taking off.”

Vance’s comments marked a stark shift from the Biden administration, which often spoke about weighing AI’s “profound possibilities” with its “risks,” as the former president put it in his farewell address in January. In the wake of Vance’s remarks in Paris, it’s clear that in the Trump White House, AI safety is out and the race for dominance is in. What does that mean for the music business and its quest to protect copyrights and publicity rights in the AI age?

“All the focus is on the competition with China, so national security has become the number one issue with AI in the Trump administration,” says Mitch Glazier, CEO/president of the Recording Industry Association of America. “But for our industry, it’s interesting. The [Trump administration] does seem to be saying at the same time that we also need to be ‘America First’ with our [intellectual property] too. It’s both ‘America First’ for IP and ‘America First’ for AI.”

Trending on Billboard

That, Glazier thinks, provides an opportunity for the music business to continue to push its AI agenda in D.C. While the president does not have the remit to make alterations to copyright protection in the U.S., the Trump administration still has powerful sway with the Republican-dominated legislative branch, where the RIAA, the Recording Academy and others have been fighting to get new protections for music on the books. Glazier says there’s been no change in strategy there — it’s still full steam ahead, trying to get those bills passed into law in 2025.

Top copyright attorney Jacqueline Charlesworth, partner at Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz, still fears that Vance’s speech — as well as President Trump’s inauguration in January, where he was flanked by top executives from Apple, Meta, Amazon and Alphabet — “reflected a lot of influence from the large tech platforms.” Many major tech companies have taken the position that training their AI models on copyrights does not require consent, credit or compensation. “My concern is that creators and copyright owners will be casualties in the AI race,” she says.

For David Israelite, president/CEO of the National Music Publishers’ Association, it’s still too early to totally understand the new administration’s views on copyright and AI. But, he says, “we are concerned when the language is about rushing to train these models — and that becoming a more important principle than how they are trained.”

Glazier holds out hope that Trump’s bullish approach to trade agreements with other nations could benefit American copyright owners and may influence trade partners to honor U.S. copyrights. Specifically, he points to the U.K., where the government has recently proposed granting AI companies unrestricted access to copyrighted material for training their models unless the rights holder manually opts out. Widely despised by copyright holders of all kinds, the music industry has protested the opt-out proposal in recent weeks through op-eds in national newspapers, comments to the U.K. government and through a silent album, Is This What We Want?, co-authored by a thousand U.K. artists, including Kate Bush, Damon Albarn and Hans Zimmer.

Organized by AI developer, musician and founder of AI safety non-profit Fairly Trained, Ed Newton-Rex, Is This What We Want? features silent tracks recorded in famous studios around London to demonstrate the potential consequences of not protecting copyrighted songs. “The artists and the industry in the U.K. have done an incredible job,” says Glazier. “If for some reason the U.K. does impose this opt-out, which we think is totally unworkable, then this administration may have an opportunity to apply pressure because of a renewal of trade negotiations.”

Israelite agrees. “Much of the intellectual property fueling these AI models is American,” he says. “The U.S. tackles copyright issues all the time in trade agreements, so we are always looking into that angle of it.”

It’s not just American music industry trade groups that have been following the Trump administration’s approach to AI. Abbas Lightwalla, director of global legal policy for the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), the global organization representing the interests of the recorded music business, says he and his colleagues followed Vance’s Paris speech “with great interest,” and that future trade agreements between the U.S. and other nations are “absolutely on the radar,” given that IFPI advocates across the world for the music industry’s interests in trade negotiations. “It’s crucial to us that copyright is protected in every market,” he says. “It’s a cross-border issue… If the U.S. is doing the same, then I think that’s a benefit to every culture everywhere to be honest.”

Charlesworth says this struggle is nothing new; the music industry has dealt with challenges to copyright protection for decades. “In reflecting on this, I feel like, starting in the ‘90s and 2000s, the tech business had this ‘take now, pay later’ mentality to copyright. Now, it feels like it’s turned into ‘take now, and see if you can get away with it.’ It’s not even pay later.”

As the AI race continues to pick up at a rapid pace, Israelite says he’s “not that hopeful that we are going to see any kind of government action quickly that would give us guidance” — so he’s also watching the active lawsuits surrounding AI training and copyright closely and looking to the commercial space for businesses in AI and IP that are voluntarily working out solutions together. “We’re very involved and focused on partnerships with AI that can help pave the way for how this technology provides new revenue opportunities for music, not just threats,” he says.

Glazier says he’s working in the commercial marketplace, too. “We have 60 licensing agreements in place right now between AI companies and music companies,” he says. Meanwhile, the RIAA is still watching the two lawsuits it spearheaded for the three major music companies against AI music startups Suno and Udio and is working to get bills like the NO FAKES Act and NO AI FRAUD Act passed into law.

“While IP wasn’t on the radar in Vance’s speech, the aftermath of it totally shifted the conversation,” says Glazier. “We just have to keep working to protect copyrights.”

Vermillio, an AI licensing and protection platform, raised $16 million in Series A funding led by Sony Music and DNS Capital, the company announced on Monday (March 3). This marks the first time Sony Music has invested in an AI music company.

Sony Music’s relationship with Vermillio dates back to 2023, when the two companies collaborated on a project for The Orb and David Gilmour. Through the partnership, fans could use Vermillio’s proprietary AI tech to create personalized remixes of the acts’ 2010 ambient album Metallic Spheres.

According to a press release, Vermillio plans to use the funds to scale operations and “continue building out solutions for a generative AI internet that enables talent, studios, record labels, and more to protect and monetize their content.”

Trending on Billboard

Vermillio’s goal is to create an AI platform that securely licenses intellectual property (IP). One of its core products is TraceID, which provides protection and third-party attribution for artists. Through it, the company claims artists and rights holders can control their data and AI rights.

Apart from its collaboration with Sony Music for the AI remix project, Vermillio has also worked with top talent agency WME to shield its clients from IP theft and find opportunities to monetize their name, image and likeness rights by licensing their data. Sony Pictures also worked with Vermillio to create an AI engine that allowed fans to make their own unique digital avatars in the style of Spider-Verse animation. Each of the fan generations were then tracked using TraceID so that all works could be tied back to the filmmakers’ original IP.

“We are setting a new standard for AI licensing — one that proactively enables consent, credit, and compensation for innovative opportunities,” said Dan Neely, co-founder/CEO of Vermillio, in a statement. “With the support of an innovation leader like Sony Music, Vermillio will continue building our products that ensure generative AI is utilized ethically and securely. At this critical moment in determining the future of AI and how to hold platforms accountable, we are proud to protect the world’s most beloved content and talent.”

“Sony Music is focused on developing responsible generative AI use cases that enhance the creativity and goals of our talent, protect their work, excite fans, and create new commercial possibilities,” added Dennis Kooker, president of global digital business at Sony Music Entertainment. “Dan Neely and the team at Vermillio share our vision that prioritizing proper consent, clear attribution and appropriate compensation for professional creators is foundational to unlocking monetization opportunities in this space. We look forward to expanding our successful collaboration with them as we work to support the growth of trusted platforms by enabling secure AI solutions that are mutually beneficial for technology innovators, artists and rightsholders.”

Amazon has partnered with AI music company Suno for a new integration with its voice assistant Alexa, allowing users to generate AI songs on command using voice prompts. This is part of a much larger rollout of new features for a “next generation” Alexa, dubbed Alexa+, powered by AI technology.

“Using Alexa’s integration with Suno, you can turn simple, creative requests into complete songs, including vocals, lyrics, and instrumentation. Looking to delight your partner with a personalized song for their birthday based on their love of cats, or surprise your kid by creating a rap using their favorite cartoon characters? Alexa+ has you covered,” says an Amazon blog post, posted Wednesday (Feb. 26).

Other new Alexa+ features include new voice filters, image generation, smart home operation, Uber booking and more. It also includes an integration with Ticketmaster to “find you the best tickets to an upcoming basketball game or to the concert you’ve been dying to go to,” according to the blog post.

Trending on Billboard

Suno is known to be one of the most powerful AI music models on the market, able to generate realistic lyrics, vocals and instrumentals at the click of a button. However, the company has come under scrutiny by the music business establishment for its training practices. Spearheaded by the RIAA, Universal Music Group, Sony Music and Warner Music Group came together last summer to sue Suno and its rival Udio, accusing the AI music company of copyright infringement “on an almost unimaginable scale.” At the time, neither AI company had admitted to training on copyrighted material.

In a later filing, Suno admitted that “it is no secret that the tens of millions of recordings that Suno’s model was trained on presumably included recordings whose rights are owned by the Plaintiffs in this case.” Its CEO, Mikey Shulman, added in a blog post that same day, “We see this as early but promising progress. Major record labels see this vision as a threat to their business. Each and every time there’s been innovation in music… the record labels have attempted to limit progress,” adding that Suno felt the lawsuit was “fundamentally flawed” and that “learning is not infringing.”

More recently, German collection society GEMA also took legal action against Suno in a case filed Jan. 21 in Munich Regional Court.

Still, a couple of music makers have sided with Suno. In October, Timbaland was announced as a strategic advisor for the AI music company, assisting in “creative direction” and “day-to-day product development.” Electronic artist and entrepreneur 3LAU has also been named as an advisor to the company.

News of Amazon’s deal with Suno comes just months after its streaming service, Amazon Music, was commended by the National Music Publishers’ Association for finding a way to add audiobooks to its “Unlimited” subscription tier in the U.S. without “decreas[ing] revenue for songwriters” — a contrast to Spotify, which decreased payments to U.S. publishers by about 40% when it added audiobooks to its premium tier.

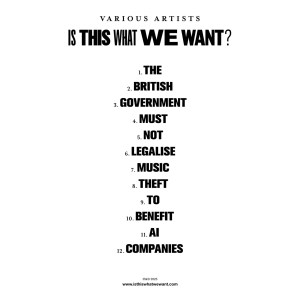

Kate Bush, Damon Albarn, Annie Lennox and Hans Zimmer are among the artists who have contributed to a new “silent” album to protest the U.K. government’s stance on artificial intelligence (AI).

The record, titled Is This What We Want?, is “co-written” by more than 1,000 musicians and features recordings of empty studios and performance spaces. In an accompanying statement, the use of silence is said to represent “the impact on artists’ and music professionals’ livelihoods that is expected if the government does not change course.”

The record was organized by Ed Newton-Rex, the founder of Fairly Trained, a non-profit that certifies generative AI companies that respect creators’ rights. The tracklisting to the 12-track LP reads: “The British government must not legalise music theft to benefit AI companies.”

Is This What We Want? is now available on all major streaming platforms.

Also credited as co-writers are performers and songwriters from across the industry, including Billy Ocean, Ed O’Brien, Dan Smith (Bastille), The Clash, Mystery Jets, Jamiroquai, Imogen Heap, Yusuf / Cat Stevens, Riz Ahmed, Tori Amos, James MacMillan and Max Richter. The full list of musicians involved with the record can be viewed at the LP’s official website. All proceeds from the album will be donated to the charity Help Musicians.

Courtesy Photo

The release comes at the close of the British government’s 10-week consultation on how copyrighted content, including music, can lawfully be used by developers to train generative AI models. Initially, the government proposed a data mining exception to copyright law, meaning that AI developers could use copyrighted songs for AI training in instances where artists have not “opted out” of their work being included.

The government report said the “opt out” approach gives rightsholders a greater ability to control and license the use of their content, but it has proved controversial with creators and copyright holders. In March 2024, the 27-nation European Union passed the Artificial Intelligence Act, which requires transparency and accountability from AI developers about training methods and is viewed as more creator-friendly.

Speaking at the beginning of the consultation, Lisa Nandy, the U.K.’s Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, said in a statement: “This government firmly believes that our musicians, writers, artists and other creatives should have the ability to know and control how their content is used by AI firms and be able to seek licensing deals and fair payment. Achieving this, and ensuring legal certainty, will help our creative and AI sectors grow and innovate together in partnership.”

Industry body UK Music said in its most recent report that the music U.K. scene contributed £7.6 billion ($9.6 billion) to the country’s economy, while exports reached £4.6 billion ($5.8 billion).

“The government’s proposal would hand the life’s work of the country’s musicians to AI companies, for free, letting those companies exploit musicians’ work to outcompete them,” said Newton-Rex in a statement on the album release. “It is a plan that would not only be disastrous for musicians, but that is totally unnecessary: the UK can be leaders in AI without throwing our world-leading creative industries under the bus. This album shows that, however the government tries to justify it, musicians themselves are united in their thorough condemnation of this ill-thought-through plan.”

Jo Twist, CEO of the British Phonographic Institution (BPI), added, “The UK’s gold-standard copyright framework is central to the global success of our creative industries. We understand AI’s potential to drive change including greater productivity or improvements to public services, but it is entirely possible to realise this without destroying our status as a creative superpower.”

Speaking to Billboard U.K. in January, alt-pop star Imogen Heap — a co-writer on Is This What We Want? — expanded on her approach to AI. “The thing which makes me nervous is the provenance; there’s all this amazing video, art and poetry being generated by AI as well as music, but you know, creators need to be credited and they need to tell us where they’re training [the data] from.”

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio