artificial intelligence

Page: 3

Trending on Billboard

Over the past few years, the revenue of the organizations that collect and distribute public performance and mechanical royalties have gone up – by a collective 7.2% in 2021, an eye-popping 28.9% in 2022 and then 7.6% in 2023. But the pandemic bust and subsequent recovery boom made it hard to see trends that would shape the future of this part of the business. With the Nov. 6 release of the organization’s Global Collections Report, though, a clearer picture of this part of the music publishing business is starting to emerge.

Revenue from music collections hit 12.59 billion euros ($13.62 billion), up 7.2% from 2023, a rate of growth not so different from the previous year, while revenue from digital sources rose 10.8% to 5.01 billion euros ($5.42 billion). This, too, seems to be falling into something of a pattern: Digital revenue jumped 35.1% in 2022, then 9.5% in 2023. Revenue from live and background music – played at concerts and in places like restaurants and bars – also seems to be settling into a groove. After falling more than 45% during the pandemic, it grew 68.5% in 2022, 21.8% in 2023, and 10.4% last year to 3.38 billion euros ($3.66 billion). Revenue from television and radio climbed 1.2% to 3.42 billion euros ($3.7 billion), after growing 11.8% in 2022 and falling 5.3% in 2023.

Related

Over the past decade, global music collections rose by more than two-thirds – and the mix of revenue has changed significantly. In 2024, revenue from digital sources made up 39.8% of collection organization revenue, while television and radio accounted for 27.1% and live and background music for 26.8%. Digital and live are expected to continue to grow, especially since live revenue in most cases is pegged to concert ticket prices.

Globally, the picture hasn’t changed as fast as some hoped. Western Europe still accounts for almost half the market (47.5%) and revenue there grew 6.6%. Including the U.S. and Canada, where revenue grew 10%, the West accounts for more than 75% of global collections. For years, publishing executives expected significant growth in African and Latin America, but so far it has not lived up to expectations – revenue from Africa grew 10% while that of Latin America rose 3.3%. The latter region’s growth was hurt by a currency decline in Argentina, while growth in Asia was hampered by a slight decline in Japan for the same reason. The standout region for growth was Eastern Europe, which CISAC counts as everything from the former Iron Curtain to Central Asia, where collections grew 17.9%.

These CISAC statistics capture a significant amount of the music publishing business – but not all of it. They include all of the revenue that goes through collecting societies that are CISAC members, most of which operate on a nonprofit or not-for-profit basis, plus private companies like BMI and SESAC. (These numbers do not include GMR, or Global Music Rights, and some other entities.) In most of the world, unlike the U.S., societies collect both public performance and mechanical rights revenue, and these numbers reflect that. CISAC does not currently account for money collected for mechanical rights by the MLC, although that may change next year. These numbers also exclude revenue collected for multi-territory online rights assigned by publishers to ICE and some other European entities. For all those omissions, however, the CISAC report is one of the better ways to get a sense of music publishing.

Related

CISAC is an organization that goes far beyond music – it includes 228 collective management organizations in 111 countries and territories – including those that collect money for the use of audiovisual works, visual art, literature and drama. Much of this non-music revenue comes from Europe, where countries have an array of collecting societies for different media. Music is the biggest source of revenue by far, however, accounting for about 90% of a 13.97-billion-euro ($15.11 billion) total, which was up 6.6% from 2023. Overall, digital revenue for all rights rose by 11.2%.

“This year’s results are testament to the adaptability and resilience of creators’ collective rights management in a rapidly changing environment,” CISAC director general Gadi Oron said in a statement distributed with the report. In the same document, CISAC president Björn Ulvaeus noted that “In 2024, authors’ societies delivered record royalties to creators worldwide. This achievement is a cause for celebration, reflecting the resilience of collective management and the value of creative works in a growing market.”

Oron and Ulvaeus also took the opportunity to issue warnings about the potential threat of generative artificial intelligence. Without proper regulation, AI “risks undermining the very foundation of creative value,” Oron writes in his foreword to the report. So far, he notes, the European Commission’s implementation of the AU AI Act has fallen short of the protections in it, which amounts to “a betrayal” that “underscores the urgency of ensuring that the rights of authors are upheld in practice, not just in principle.”

Related

In his own foreword, Ulvaeus takes a similar tone. A study commissioned by CISAC projected that as much as a quarter of creators’ royalties could be lost without AI regulation as the market for AI-generated content could reach 64 billion euros in three years. “This is value flowing away from the individuals who give culture its meaning,” Ulvaeus writes. “I have urged that creators must be at the decision table, not on the outside looking in.”

Trending on Billboard

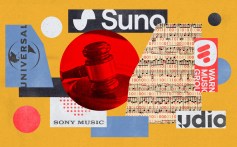

THE BIG NEWS: Universal Music Group and artificial intelligence music service Udio reached a landmark agreement last week to end their lawsuit – the first major settlement in the battle over the future of AI music. Here’s everything you need to know.

The deal, announced Wednesday, will end UMG’s allegations that Udio broke the law by training its AI models on vast troves of copyrighted songs — an accusation made in dozens of other lawsuits filed against booming AI firms by book authors, news outlets, movie studios and visual artists. The agreement involves both a “compensatory” settlement for past sins and an ongoing partnership for a new, more limited subscription AI service that pays fees to UMG and its artists.

Related

-The agreement is much more than a legal settlement, Udio CEO Andrew Sanchez told Billboard’s Kristin Robinson in a detailed question-and-answer session just hours after the news broke: “We’re making a new market here, which we think is an enormous one.”

-The deal between UMG and Udio will resolve their legal battle, but broader litigation involving rival AI firm Suno and both Sony Music and Warner Music is still very much pending. Are more settlements coming? Does the deal impact the case? Go read my look-ahead analysis of the ongoing court battle.

-Will AI do more harm than good for the music business? That’s the question Billboard’s Glenn Peoples is asking – and financial analysts don’t have a clear answer. Some believe AI’s negatives outweigh its positives, while others see mostly upside. Maybe it’s just too early to know, Glenn says: “In the near term, expect more deals like UMG’s partnership with Udio. Over the long term, expect to be surprised.”

-Artist advocates are already demanding answers about how exactly this whole thing will work. According to the Music Artists Coalition, talk of “partnership” and “consent” are all well and good, but details are what matter: “We have to make sure it doesn’t come at the expense of the people who actually create the music,” MAC founder Irving Azoff said.

Related

-To put it lightly, Udio subscribers were not big fans of the settlement, which saw the company immediately disable downloads – even for songs that users created long before the deal was reached. After two days of outrage and threats of legal action, Udio said it would open a 48-hour window for users to download their songs. But with wholesale changes to the platform coming soon, will that be enough to satisfy them?

You’re reading The Legal Beat, a weekly newsletter about music law from Billboard Pro, offering you a one-stop cheat sheet of big new cases, important rulings and all the fun stuff in between. To get the newsletter in your inbox every Tuesday, go subscribe here.

Other top stories this week…

AINT OVER YET – Drake is now formally appealing last month’s court ruling that dismissed his defamation lawsuit against Universal Music Group (UMG) over Kendrick Lamar’s diss track “Not Like Us,” prolonging a messy legal drama that has captivated the music industry and, at times, drawn ridicule in the hip-hop world.

DIDDY APPEAL – Sean “Diddy” Combs is appealing too – and he’ll get a fast-track process to do it. With such cases sometimes lasting years, his lawyers argued that he could be nearly finished with his three-ish year prison sentence by the time an appellate court rules on his prostitution convictions.

Related

POT SHOTS – Offset is facing a new civil assault lawsuit claiming he punched a security guard in the face at a cannabis dispensary in Los Angeles after being asked to show his I.D., sending the staffer to the emergency room.

MASSIVE FINE – Fugees rapper Pras Michel must forfeit a whopping $64 million to the government following his conviction on illegal foreign lobbying and conspiracy charges, a federal judge says, overruling his protests that it’s “grossly disproportionate.”

DRAKE SUED – Drake and internet personality Adin Ross are facing a class action accusing them of using “deceptive, fraudulent and unfair” practices to promote online sweepstake casino Stake and “encourage impressionable users to gamble,” including using house money to do it.

DRAKE NOT SUED – Another class action, this one against Spotify, claims that the platform has turned a “blind eye” to streaming fraud and allowed billions of fake plays. It alleges that Drake is one of the most-boosted artists, but the rapper is not named as a defendant nor accused of wrongdoing.

Related

FAIR TRADE? Cam’ron is suing J. Cole over allegations he reneged on a deal to swap featured credits – claiming he provided a verse for Cole’s “Ready ’24” but that Cole repeatedly declined to do the same, or even appear on Killa Cam’s podcast.

CUSTODY TRUCE – Halle Bailey and DDG temporarily agreed to share custody of their son and drop domestic violence claims against each other, putting a halt to the musicians’ messy legal battle after months of back and forth.

NEWJEANS, SAME LABEL – A Korean court issued a ruling rejecting NewJeans’ attempt to break away from its label ADOR, dealing a major victory to the HYBE subsidiary in its closely-watched legal battle with the chart-topping K-pop group.

DEPOSITION DRAMA – A judge says Tory Lanez must sit for a deposition in litigation stemming from his alleged shooting of Megan Thee Stallion in 2020. The case was filed by Megan against gossip blogger Milagro Gramz, who she claims spread falsehoods about the shooting.

NOT VERY CASH MONEY – Former Hot Boys member Turk is being sued by a concert promoter over online threats that supposedly threatened to derail a Cash Money Records reunion tour featuring Birdman and Juvenile

UGLY DIVORCE – Sia and her estranged husband are fighting over custody of their child amid divorce proceedings — and the crossfire is getting ugly. Among other claims, he says the pop star is a drug addict who can’t care for a baby, and she says he was investigated over child pornography.

Trending on Billboard Danish rights organization Koda has filed a lawsuit against AI music company Suno, alleging that it infringed on copyrighted works from its repertoire — including songs by Aqua, MØ and Christopher. Koda claims that Suno used these works to train its AI models without permission and has concealed the scope of what […]

Trending on Billboard

The annual Music Tectonics conference kicks off Tuesday (Nov. 4), bringing together music industry professionals, entrepreneurs, and investors alongside the Pacific Ocean in Santa Monica, Calif.

Music Tectonics was founded in 2019 by Dmitri Vietze and his team at public relations firm Rock Paper Scissors. The three-day gathering not only has a great location — the first two days are beachside — but a valuable position on the calendar: After Music Tectonics, music industry events wind down to accommodate the holidays and won’t pick up until Grammy week in Los Angeles in late January.

Related

The first day of Music Tectonics’ three-day event takes place at the Santa Monica Pier Carousel. On Wednesday, the conference moves to the Annenberg Community Beach House about a mile up the coast. Thursday’s events — which are focused on entrepreneurism and startups — take place at Expert Dojo, a startup accelerator located near the Santa Monica Pier. A closing party will take place at Universal Music Group’s nearby headquarters.

To help attendees know what to expect from the event, Billboard is highlighting some of the most promising programming.

Optimization is Not Enough: Are You Ready for Streaming’s Reckoning?

MIDiA Research’s Tatiana Cirisano talks about the future of music streaming. In a fireside chat moderated by Music Tectonics founder Dmitri Vietze, Cirisano will argue that focusing on optimization — getting the most out of existing subscribers with higher prices and value-added perks — won’t attract the next generation of customers.

The Investor Panel

AI startups have commandeered an astounding 51% of venture capital funding in 2025, according to CB Insights. To find out if music is less one-sided, a panel of seasoned investors will discuss what business ideas excite them and where music and technology are headed. They are also expected to give attendees tips on how to pitch them.

Featured speakers: Aadit Parikh from Sony Ventures, Conor Healy from Yamaha Music Innovations Fund, and Lucas Cantor Santiago from Mindset Ventures. Entrepreneur and advisor Angel Gambino will moderate.

What Everyone Should Know about the New Frontiers: Music, Gaming, AI, and Beyond!

If you want to know where the music business is headed, it’s best to hear from the people who help build the products, create the partnerships and advise the companies that are pushing music into the future. The panelists’ many decades of expertise covers streaming platforms, gaming, social media and musical instruments.

Featured speakers: Elizabeth Moody from Granderson Des Rochers, Paul McCabe from Roland, and Kirsten Bender from Universal Music Group. Music Tectonics’ Dmitri Vietze will moderate.

Related

Tools of the Trade: Platforms That Launch You Out of DIY

The best conference panels are often those that offer practical tips that are worth the price of admission. At the “Tools of the Trade” panel, music professionals will give their thoughts on the services that help independent musicians operate in the marketplace.

Featured speakers: Kevin Lazaroff from Amuse, Charles Alexander from ViNiL, and Crystal Desai from HiFi Labs. Tetris Kelly from Billboard will moderate.

The New Direct-to-Fan E-Commerce

“The future of fandom is direct,” says the page for the panel on direct-to-consumer e-commerce. In fact, the future is already here. Direct-to-consumer sales accounted for “two-thirds to 75%” of sales of Universal Music Group’s new releases, COO Boyd Muir said during the company’s Oct. 30 earnings call.

Featured speakers: Joshua Stone from Stuff.io, Shannon Herber from Wise River Consulting, and Fabrice Sargent from Bandsintown. Billboard’s Taylor Mims will moderate.

Trending on Billboard

A few years into the debate about AI’s potential economic impact on music, the jury is still out.

AI could be great for the music business, enabling new products and creating new revenue streams for artists and songwriters. Universal Music Group (UMG) has said as much. “We believe the commercial opportunity is potentially very significant,” chief digital officer Michael Nash said during the company’s earnings call on Thursday (Oct. 30), a day after it announced a licensing deal with AI music generator Udio. “These new products and services could constitute an important source of incremental additional new future revenue for artists and songwriters.”

Related

Then again, AI could erode record labels and music publishers’ businesses by flooding the internet with inexpensively made music that takes some — not all — of their market share. Record labels have already lost market share to independent artists in recent years, and AI could be either a continuation or acceleration of existing trends.

Two years ago, analysts at Barclays Research were dismissive of AI-generated music’s threat to the established music business. The general population might have access to music-making tools, but, Barclays reasoned, the quality of the music was poor, and songs created by faceless software housed on computer servers couldn’t create the human connection that listeners desire. Record labels and music publishers could be hurt if social platforms pushed AI music, but the money-saving tactic could run into legal roadblocks, they said. For all the initial hoopla about AI’s ability to upset the status quo, too many questions at the time remained unanswered.

Today, though, Barclays is singing a different tune, and advancements in AI platforms have answered some of their earlier questions. Now, the analysts are more convinced of AI music’s potential to erode record labels’ market share and weaken their financial standing. The quality of music has “improved significantly,” they wrote in a Tuesday (Oct. 28) report titled “AI in Music: Danger Zone,” adding that it’s “hard to differentiate between human music and AI music.” Fans still crave connections with human artists, they wrote, but as opposed to their earlier take, they conceded that AI music represents a threat to the music establishment.

Related

In the Barclays analysts’ view, AI is a mixed bag of gains (such as AI-enabled superfan tiers) and losses (lower royalties from social media platforms’ adoption of cheap AI music). Overall, though, they believe the damage that AI can create will outweigh its benefits. Their bottom line: In an average scenario, UMG takes a 1% hit to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) and Warner Music Group’s EBITDA drops 4%. A worst-case scenario calls for deeper losses. A best-case scenario sees AI providing a boost.

Not everybody is in the Barclays camp, however. Despite advancements in the quality of music produced by AI platforms, analysts at J.P. Morgan are sticking with their opinion from 2023 that AI will not have “a meaningful impact on industry revenues.” Analysts wrote in a note to UMG investors on Monday (Oct. 27) that AI risks have been “negated” and “controlled” by the company’s efforts in recent years to get streaming platforms to prioritize and reward professional artists over mass-produced, low-quality recordings.

Like Barclays, J.P. Morgan believes market erosion is a genuine threat to UMG’s market share. But J.P. Morgan analysts see much more upside in AI. (Notably, J.P. Morgan’s analysis was less thorough; unlike Barclays, it didn’t put a dollar value on AI’s potential impact.) They note that UMG will benefit from AI artists’ need for publishers and record labels (which jibes with Billboard’s assessment of Hallwood Media’s impact on Xania Monet’s on-demand streams). AI can also generate revenue streams from new licensing opportunities and make listening to music more enjoyable, they write.

Related

The major labels and publishers haven’t signed or created AI artists yet, but if they do, J.P. Morgan believes they will benefit from economics that are superior to their deals with human artists and songwriters. It’s not a stretch: To capture some of the market share that has shifted to independent artists, UMG has invested heavily in artist services by building up Virgin Music Group and attempting to acquire Downtown Music Holdings (the European Commission will announce its decision on the proposed merger in February 2026). If AI artists are to compete in the marketplace, they will need the same services that are available to human artists, such as promotion, distribution, copyright administration and public relations.

One thing is certain: Because AI music is in its infancy, trying to figure out its long-term trajectory is difficult. When the music industry began navigating the shift from physical to digital in the late ‘90s, few people could have guessed that the marketplace of 2025 would be dominated by subscription royalties and that download revenue would be almost nonexistent. When Napster launched in 1999, nearly a decade before the iPhone debuted, imagining the influence of an app like TikTok would have been nearly impossible. Music companies got to this point by enforcing the value of their intellectual property through a few decades of licensing agreements and lawsuits.

In the near term, expect more deals like UMG’s partnership with Udio. Over the long term, expect to be surprised.

Trending on Billboard

Music Artists Coalition (MAC), a nonprofit dedicated to advocating for music creators, has responded to Universal Music Group’s new AI deal with Udio, asking questions about how artists will be compensated. “We’re cautiously optimistic but insistent on details,” said Jordan Bromley, leader at Manatt Entertainment and board member of MAC, in a press release put out by MAC on Friday (Oct. 31).

The UMG-Udio deal, which was announced Wednesday night (Oct. 29), is multifaceted. First, it involves a “compensatory” legal settlement for UMG, which sued Udio last summer, along with the other major music companies, for copyright infringement of their sound recordings during Udio’s training process. (Sony and Warner’s lawsuit against Udio is ongoing.)

Related

It also provides go-forward licensing agreements for UMG’s recorded music and publishing assets, which is said to open up a new revenue stream for the company and its signees who decide to opt in. Those artists and songwriters who participate will be compensated for both the training process of the AI model and for its outputs, according to a source close to the deal.

As part of the agreement, Udio plans to pivot its offerings significantly. In 2026, the company will launch a new platform “powered by new cutting-edge generative AI technology that will be trained on authorized and licensed music. The new subscription service will transform the user engagement experience, creating a licensed and protected environment to customize, stream and share music responsibly, on the Udio platform.” This will include new tools that let fans remix, mashup and create songs in the style of participating UMG artists. It will also allow fans to use UMG artist voice models.

Opting into the Udio deal is not a one-size-fits-all approach. According to a recent interview with Udio CEO Andrew Sanchez about the deal, the company “[has] built and invested an absolutely enormous amount into controls. Controls over how artists’ songs can be used, how their styles can be used, really granular controls…One of the things that you’ll see is we’re going to launch with a set of features that has a spectrum of freedom that the artist can control.”

Related

One area that Sanchez and UMG’s announcement about the deal did not provide clarity on was how exactly participating artists will be compensated. This is why MAC put out a press release on Friday (Oct. 31) asking exactly what is going on — and noting the organization is only “cautiously optimistic” about the agreement.

As Irving Azoff, top artist manager, entrepreneur, board member and founder of MAC, put it in the announcement: “Every technological advance offers opportunity, but we have to make sure it doesn’t come at the expense of the people who actually create the music — artists and songwriters. We’ve seen this before — everyone talks about ‘partnership,’ but artists end up on the sidelines with scraps. Artists must have creative control, fair compensation and clarity about deals being done based on their catalogs.”

The press release goes on to say that while MAC appreciates that the deal is “opt-in” and with “granular control,” the organization still has questions, which are quoted below:

“Meaningful consent: How do artists actually control what uses they authorize? What happens when multiple songwriters or performers on a single song disagree about participation?”

“Revenue splits: What percentage of revenue goes to artists versus the label versus the AI company when their music is used to train models or generate new works?”

“Data and deal transparency: Was settlement money paid? How will that be distributed to artists? Will artists’ pay-outs for a new revenue stream just be applied to old unrecouped balances? Will artists see exactly how their work is being used within the AI system and have ongoing visibility into its use?”

Related

“Artist opt-in sounds promising, but participation without fair compensation isn’t partnership; it’s just permission,” said Ron Gubitz, MAC’s executive director, in the press release. “Artists create the work that makes these AI systems possible. They deserve both control over how their work is used and appropriate compensation for its value generation. It’s the three C’s: consent, compensation, and clarity.”

“The music industry is at a crossroads,” Gubitz added. “The decisions being made right now will shape how music gets created, distributed, and monetized for decades to come. That’s exactly why MAC exists — to ensure artists have a seat at the table when those decisions are made.”

Bromley added: “True partnership requires appropriate oversight and remuneration for all involved parties. The industry needs to get this right — for artists, for fans, and for the future of music itself.”

Trending on Billboard

Udio now says it will briefly allow subscribers to download their existing songs following widespread backlash to drastic changes made to the platform following the AI firm’s licensing settlement with Universal Music Group (UMG).

The move comes in response to growing outrage — and even threats of legal action — from users after Udio struck the UMG deal, under which the AI company immediately barred its paying subscribers from downloading their own songs, even those they had created long before the UMG deal.

Related

In the statement posted late Thursday (Oct. 30) to Reddit, Udio said it would provide a 48-hour window starting Monday (Nov. 3) for all users to download their existing songs. Any songs downloaded during that time will be covered by the prior terms of service that existed before the UMG settlement.

“Not going to mince words: we hate the fact we cannot offer downloads right now,” Udio CEO Andrew Sanchez wrote in that post. “We know the pain it causes to you, and we are sorry that we have had to do so.”

In the Reddit post, Sanchez also tried to explain the reasons for the original change, saying that Udio is a “small company operating in an incredibly complex and evolving space” that had chosen to partner directly with artists and songwriters. “In order to facilitate that partnership, we had to disable downloads,” he said.

Related

If the download ban is a requirement of the legal settlement with UMG, how can Udio now reverse course and allow users to download their songs? Sanchez said Udio had “worked with our partners to help make this possible.” A spokesman for UMG did not return a request for comment.

Any existing songs that are downloaded during next week’s window will be owned by the users who made them. Under Udio’s terms of service, the company grants all users of the platform — paid subscribers or free users — any ownership rights to their songs, including express permission to use them for commercial purposes. The company does require users of the company’s free tier to include attribution that the song was made with Udio.

The deal between UMG and Udio, announced Wednesday (Oct. 29), will end UMG’s allegations that Udio broke the law by training its AI models on vast troves of copyrighted songs. Under the agreement, Udio will pay a “compensatory” settlement, and the two will partner on a new subscription AI service that pays fees to UMG and its artists, and allows artists to opt in to different aspects of the new service.

Related

The revamped Udio will be quite a bit different from the current service — a “walled garden” where fans can stream their creations but cannot take them elsewhere. While the new version won’t launch until next year, the firm immediately disabled all downloading on Wednesday, a move that drew predictable backlash from its users, particularly on the company’s Reddit sub.

“This feels like an absolute betrayal,” wrote one Reddit user. “I’ve spent hundreds of $$$ and countless hours building tracks with this tool,” wrote another. “No one warned us that one day, we wouldn’t even be able to access our own music. You can’t just pull the plug and call that a ‘transition.’”

Some Udio subscribers even floated the idea of legal action: “What you have committed is fraud. Just so you understand,” wrote one user. “You may not feel any legal ramifications immediately, but not everyone who used your platform is without resources.”

The window for downloads will kick off on Monday, but it’s unclear exactly when. Udio said in the post that it would “provide the exact starting time and end time” on Friday (Oct. 31), but had yet to do so by Friday afternoon. An Udio spokesperson did not offer more details when reached by Billboard for comment.

Trending on Billboard

On Wednesday night (Oct. 29), Universal Music Group (UMG) and AI music company Udio announced they had reached a strategic agreement. Importantly, this agreement not only settled UMG’s involvement in the massive copyright infringement litigation the major labels brought against Udio and another AI music company, Suno, last summer, but also paved the way for the two companies to “collaborate on an innovative, new commercial music creation, consumption and streaming experience,” according to the announcement.

Related

The newly revamped version of Udio is set to debut in 2026, and it will feature fully-licensed UMG sound recordings and publishing assets that are totally controlled by UMG — but only those from artists that choose to participate.

Here, Billboard looks at the deal more deeply and answers some questions that have arisen in the wake of the first-of-its-kind agreement.

Why did UMG and Udio decide to come together and settle this week?

It’s hard to know exactly what happened behind closed doors, but reports that the major music companies had been in talks to settle with Udio — and Suno, which was also sued in a nearly identical lawsuit by the majors — have been circulating since this summer, making it relatively unsurprising to hear that at least one deal has been finalized.

One clue as to why there was incentive to settle here comes from a recent Barclays Research report on the majors’ lawsuits against the AI music firms, which stated that it could be “prohibitively expensive to lose” for Udio, much more than Suno, given the two firms had raised $10 million and $125 million, respectively, at the time the report was published on Tuesday (Oct. 28). Even a tough settlement, the report states, “would likely only mean the disappearance of Udio.”

The timing of the press release about the UMG-Udio deal also arrived the night before UMG’s Q3 earnings call, which took place yesterday (Oct. 30). The company has a history of announcing big news just before earnings calls in general, including one instance when UMG reached an agreement with TikTok the night before earnings in 2024 after a three-month standoff.

Related

What exactly will this 2026 version of Udio entail?

The new version of Udio will feature a number of tools to allow users to remix, mash up and riff on the songs of participating UMG artists. Users will also be able to create songs in the style of participating artists and use some artists’ voices on songs.

According to Udio CEO Andrew Sanchez, who spoke to Billboard just after the deal was announced, “[Udio is] going to involve all kinds of AI models, like a base model… The best way to explain it, [is it] will have sort of like flavors of the model that will be specific to particular styles or artists or genres. And this, again, provides an enormous amount of control.”

How can UMG artists and songwriters participate, and can they get paid for that?

Yes, UMG artists and songwriters will be remunerated for participating in Udio. According to a source close to the deal, this will include financial rewards for both the training process of the AI model and for its outputs. The details of exactly how that payment will work beyond this are unclear. Sanchez declined to answer a question about whether the model uses attribution (tracing back which songs in a training dataset influenced the outputs of a model) or digital proxies (a selected benchmark, like streaming performance, used to determine the popularity of songs in a dataset against others overall) as a way to determine payment — two of the most often proposed methods of AI licensing remuneration.

This answer is also made more complicated when considering the breadth of AI tools Udio plans to offer on its service. Importantly, artists can pick and choose exactly which Udio tools they “opt-in” to: “We’re going to launch with a set of features that has a spectrum of freedom that the artist can control,” Sanchez said. “There are some features that will be available to users that will be more restrictive in what they can do with their artists or their songs. And then there will be others that are more permissive. The whole point of it is not only education but just meeting artists at the levels they’re comfortable with.”

Related

Who is the target audience for the newly revamped Udio?

According to Sanchez, it’s fans: “We want to build a community of superfans around creation. As we say internally, it’s connection through creation — whether that’s with artists or that connection with other music fans. We want to lean into that. I think it’s going to be a huge asset for artists and fandoms.”

Are Sony and Warner still pursuing their lawsuits against Udio?

Yes, for now. UMG’s settlement and deal with Udio does not impact Sony Music and Warner Music Group’s lawsuit against Udio for widespread copyright infringement. While some industry onlookers posit that Sony and Warner are more encouraged to settle now that UMG is no longer pursuing litigation against Udio, there’s no indication that these companies are definitely planning to do so yet.

Why are some Udio users upset about this deal?

By doing this deal with UMG, Udio has agreed to a major pivot in its offering to users. Currently, the site is known for helping users make songs from simple text prompts, which they can then export and upload to streaming services, share on social media — or whatever they want to do.

Users are particularly upset because, as part of this deal with UMG, Udio immediately removed its users’ ability to download their work from the service. Angry subscribers gathered on a subreddit to complain. “This feels lie an absolute betrayal,” wrote one user. “I’ve spent hundreds of $$$ and countless hours building tracks with this tool,” wrote another. “No one warned us that one day, we wouldn’t even be able to access our own music. You can’t just pull the plug and call that a ‘transition.’”

Related

In a statement to Billboard on Thursday (Oct. 30), an Udio spokesperson said that disabling exports on the platform is “a difficult but necessary step to support the next phase of the platform and the new experiences ahead.” On Friday (Oct. 31), Udio relented slightly, writing on Reddit that starting Monday (Nov. 3), the platform will give users a 48-hour window to download their existing songs — and that any songs downloaded during that time will be covered by the terms of service that existed before the UMG deal was signed.

The move to restrict downloads in the long term may prove to be more than just an inconvenience for users — Udio could also be hit with legal claims over it. There could be arguments made that disabling downloads was a breach of the subscription contract that Udio signed with users, or that Udio falsely advertised its services in violation of consumer protection laws. It wouldn’t be the first time this has happened in recent memory: Just last year, Amazon Prime users brought claims like this over changes to the cost of ad-free movie and TV streaming for subscribers.

Trending on Billboard

Universal Music Group and Udio have settled their legal battle by striking a deal for a fully-licensed artificial intelligence music platform. But the broader litigation involving rival AI firm Suno and both Sony Music and Warner Music is still very much pending.

The deal, announced Wednesday, will end UMG’s allegations that Udio broke the law by training its AI models on vast troves of copyrighted songs. Under the agreement, Udio will pay a “compensatory” settlement and the two will partner on a new subscription AI service that pays fees to UMG and its artists, and allows artists to opt in to different aspects of the new service.

Related

But that agreement will not resolve the entire legal battle, in which all three majors teamed up last year to sue both Udio and Suno — the other leading AI music firm — for allegedly “trampling the rights of copyright owners” by infringing music on an “unimaginable scale.”

For now, Sony and Warner will continue to litigate their case against Udio, but a settlement like the one struck by UMG obviously creates a framework for them to reach a similar deal. The revamped Udio 2.0 will not be an exclusive UMG partner, according to sources close to the situation — meaning it’s able to strike similar catalog licensing deals with Sony and Warner, as well as any other parties.

Udio has ample incentive to do so. Past experience has shown that music licensing for tech platforms is something of a zero-sum proposition; it often doesn’t work for users if you have glaring gaps in your catalog of songs. Spotify wouldn’t be nearly as ubiquitous if it were missing catalogs by Taylor Swift, Drake or The Beatles, while TikTok’s standoff with UMG last year ended up impacting non-UMG recording artists like Beyoncé and Adele due to rights being owned by different companies.

In striking the deal, Udio has also effectively put its cards on the table: it wants to be the music industry’s AI good guy. Though not legally impossible, it’s hard to argue in court that you don’t need training licenses and artist consent while touting the benefits of both in press releases. Udio has also already made concrete changes to its platform, including controversially disabling downloads for its existing subscribers — a further sign that it’s no longer looking to fight it out.

Related

It’s worth noting that the settlement makes for odd bedfellows in any ongoing litigation. The same team of lawyers that repped UMG in its claims against Udio — now settled with a first-of-its-kind partnership — is also representing competitors Sony and Warner as they continue to sue that company. Ditto for Suno, which is defended by the same team of attorneys as Udio, which just agreed to sign a licensing deal that’s antithetical to Suno’s core argument that no such deals are needed.

But such situations are par for the course for cases like these, where industry rivals team up for a legal case, and each company on both sides almost certainly signed agreements waiving any legal right to argue that their lawyers have a conflict of interest.

The case against Suno, on the other hand, looks more likely to keep going. All three majors are still suing that company, and Suno has long been seen in industry circles as more the more combative of the two. One can’t imagine that Suno’s will to fight will be reduced by the Udio deal; if anything, it has a clearer runway to AI music dominance now that its largest text-to-audio rival has effectively left the space to cultivate its own walled-off garden.

The Suno lawsuit remains at the earliest stage, where a defendant will file a motion to dismiss a case, which is typically the first big ruling in a civil litigation. If both sides decide to fight it out, the case and resulting appeals could go on for years into the future. But the key battle lines of the litigation are already clear.

The multi-million-dollar question is whether training AI platforms like Suno on millions of unlicensed copyrighted songs counts as “fair use,” a legal doctrine that allows for the reuse of protected works in certain circumstances. That issue is also at the heart of dozens of other lawsuits filed against booming AI firms by book authors, news outlets, movie studios, comedians and visual artists — meaning it might really be more of a trillion-dollar question.

Can Suno prevail on that point, making Udio look silly for settling so early? The proverbial jury is very much still out.

Related

One federal judge, ruling on a major case against Anthropic, sided resoundingly with AI firms, saying that unlicensed training was clearly a fair use because it was no different than a human writer taking inspiration from copyrighted books they had read. But another judge ruled that such training would be illegal “in many circumstances” and that AI firms expected to generate “trillions” in profits “will figure out a way to compensate copyright holders.”

A separate, emerging flashpoint in the case is whether Suno broke the law by “stream-ripping” its training songs from YouTube. That’s a key issue in the wake of a court ruling this summer that said AI training on copyrighted works itself is fair use, but that using illegally-obtained works to do so could lead to billions in damages for AI firms.

In the wake of this week’s Udio settlement, the record labels likely see that deal as setting a helpful precedent: “See, AI companies do need licenses to train their models — Udio just took one.” And in that same vein, when it comes to that all-important courtroom battle over fair use, those same music companies likely view this week’s Udio deal as potential legal ammo.

A key factor in the fair-use analysis is whether exploiting a copyrighted work for free caused market harm — whether it hurt the ability of the original author to monetize their own creative output. A major licensing deal with a direct competitor would seem to be a very obvious market that would be harmed by the conduct of Suno, which says it can build its AI models without such deals.

But that argument has already been rejected in both of those earlier fair-use rulings. Even for the judge who said AI training would be illegal in most circumstances, that kind of argument would be “circular” — since essentially any copyright owner could argue that the specific thing they’re suing over is a lost market opportunity. That means the Udio deal might help the labels in the business world and the court of public opinion, but likely not in actual court. For now, time will tell.

For deeper reading, go check out the full lawsuits against Suno and Udio, and go read the responses from Suno and Udio. And stick with Billboard for updates as the cases move ahead.

Trending on Billboard Universal Music Group and Stability AI have announced a strategic partnership to develop music creation tools powered by “responsibly” trained generative AI. The two companies said on Thursday that the collaboration will aim to support artists, producers and songwriters by integrating AI into the creative process while ensuring commercial safety and proper […]

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio