tiktok

Page: 2

VCG / TikTok / Donald Trump

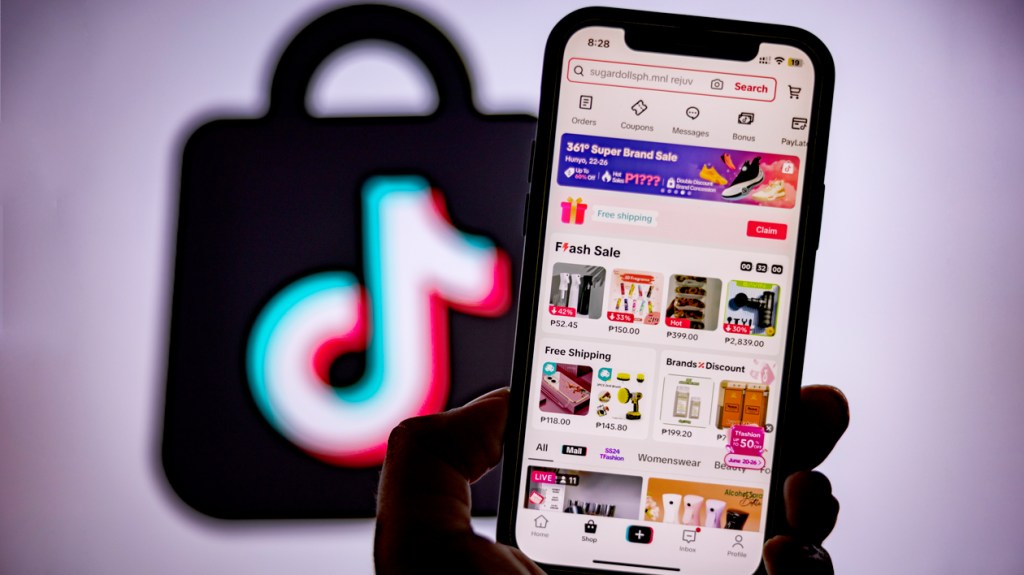

US TikTok users, you still have time to make your dance videos after Donald Trump extended the deadline for a third time, allowing the platform to divest from its Chinese-owned parent company, ByteDance, or face a US ban.

Notorious liar, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt, confirmed in a statement on Tuesday that Felon 47 will sign an executive order allowing for another 90-day extension, pushing the new deadline to mid-September.

Leavitt said the Trump administration will be “working to ensure this deal is closed so that the American people can continue to use TikTok with the assurance that their data is safe and secure.”

When Trump signed the first extension, it provided TikTok’s US service providers, which are subject to the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act, with protection from the hundreds of billions in penalties they would face if they continued to operate the app online and in US app stores.

According to The Verge’s reporting, that legal cover wasn’t rock solid because Trump’s extensions are not codified into law, which was passed overwhelmingly by a bipartisan vote in Congress and subsequently upheld as constitutional by the Supreme Court.

There Was A Tentative Agreement In Place Before Trump’s Tariffs Killed It

The website previously reported that ByteDance and a coalition led by Oracle were close to a deal in April, but thanks to Trump’s abuse of tariffs, which sank the tentative agreement.

Even though the “trade war” between China and the US has cooled down, there is still no word on whether the old deal is back on the table or if a new agreement is being discussed.

Additionally, it wasn’t guaranteed that ByteDance would be willing to include TikTok’s algorithm, which powers its video recommendations.

Additionally, several lawmakers, including critics of the “divest or ban law,” are sounding the alarm over Trump’s repeated extensions, calling them “untenable and illegal.”

We remain curious to see how this drama unfolds, as it appears there is no deal in sight.

HipHopWired Featured Video

President Donald Trump is set to sign an executive order this week extending the deadline for TikTok’s Chinese parent company to divest the popular video-sharing app, marking the third such extension. The move comes after a previous 75-day reprieve granted in April, which aimed to keep TikTok operational in the U.S. while a potential sale […]

CMAT’s newest single, “Take A Sexy Picture Of Me,” has a lightning-in-a-bottle quality that nothing she had released previously could quite compare.

The track, which will feature on the country-pop songwriter’s third LP Euro-Country (due Aug. 29 via AWAL), is bright, hooky and possessed of a subtle emotional pull. Under a soulful, spacious melody, the tone shifts continually: from self-reflection to blame-laying, from denial to weariness, frustration and regret.

So as much as this irresistible earworm encapsulates the Song of the Summer ethos with its easy, forthright and effortlessly cool arrangement, it also in a way defies it. It offers a pained and pointed depiction of body image struggles in a world of constant online commentary — evoking a sunlit mood with lyrics rooted in a wider, meaningful conversation. CMAT (an acronym of Ciara Mary-Alice Thompson) recently explained to BBC 6 Music that the track is about the mental anguish she has experienced, having previously received a flood of “nasty comments” on her physical appearance.

Trending on Billboard

Since its release last month, “Take A Sexy Picture Of Me” has taken on a life of its own, picking up significant traction on TikTok while also translating into real-world success. What started as a playful dance challenge by app user Sam Morris, a 37-year-old content creator based in Brighton, has snowballed into a trend. The routine follows along with the words of the second verse — “I did the butcher/ I did the baker/ I did the home and the family maker/ I did schoolgirl fantasies” — with participants miming chopping and baking actions.

Dubbed the “Woke Macarena” in reference to its simple choreography, the song has soundtracked over 28,000 TikTok videos in recent weeks, with stars such as Lola Young and Julia Fox getting involved. CMAT, meanwhile, is currently in the midst of an extensive festival run: at the end of May, she thrilled a Main Stage crowd at London’s Wide Awake festival, while a Pyramid Stage slot at Glastonbury is on the horizon. Last week (June 6), she supported Sam Fender at London Stadium in front of an audience of 82,500 — the venue’s biggest sold-out show to date.

Prior to this, CMAT and her band delivered an electrifying rendition of “Take A Sexy Picture Of Me” on Later… With Jools Holland, kicking off the Euro-Country campaign in earnest. The performance proved that she wants viewers to understand what she’s singing about on the deepest level possible, and if that requires theatrical emotions and dancing, she is more than willing to oblige. It wouldn’t be remiss, then, to suggest that prestige slots on U.S. late night shows may soon come along.

“CMAT is firmly and deservedly positioning herself as one of this summer’s breakout stars,” says Adam Read, music programs manager at TikTok UK. “This is a track that speaks directly to identity, self-image and transformation, all while being incredibly catchy. The fact that the choreography took shape organically and is now being performed at live shows by entire crowds is exactly the kind of cultural crossover we love to see.”

Unlike this time last year, when Sabrina Carpenter’s smash hit “Espresso” was dominating the British (and global) airwaves, there arguably hasn’t been a Song of the Summer frontrunner just yet. Alex Warren’s ballad “Ordinary” has remained firmly at the summit of the Official U.K. Singles Chart for the past 12 weeks — the longest-running U.K. No. 1 of the 2020s — yet its sighing, plaintive melody doesn’t quite speak to the easy-breezy feel of the season.

Read and the team at TikTok UK, however, have predicted “Take A Sexy Picture Of Me” as a contender, alongside Afrobeats star Darkoo’s “Like Dat” and Charli xcx’s “Party 4 U.” The latter is a 2020 fan favorite that peaked at No. 42 on the Billboard 200 last month (May 31), with Atlantic Records having pushed it towards U.S. contemporary hit radio over the spring.

With over 575,000 video creations under the #SongOfTheSummer hashtag, TikTok is a key launchpad for new music at this time of the year. CMAT, meanwhile, has gained over 26.6 million content views in the past month alone, leading to a 71% growth in her follower count and, in turn, pushing her monthly Spotify listeners over the 1 million mark. The song is continuing to climb Spotify’s Viral 50 — Global chart and is approaching 4 million streams on the service.

That begs the question: is this CMAT’s crown to take? The Dublin-raised musician has perhaps never been better primed to make a mainstream crossover. Her second LP, 2023’s Crazymad For Me saw her break the Top 40 on the Official U.K. Albums Chart for the first time (No. 23), while also scooping Mercury Prize, BRIT and Ivor Novello nominations; the former is a notable feat, given that 2022 debut If My Wife New I’d Be Dead failed to crack the Top 75.

Shrewd marketing from the Sony-owned AWAL, meanwhile, has also played a role in the success of “Take A Sexy Picture Of Me”; the track recently landed a glowing feature in The New York Times. “We realized very quickly that this would be an opportunity to broaden her out to new audiences,” says Victoria Needs, senior vp at AWAL. Having announced a worldwide deal with CMAT four years ago, Needs adds that the label’s vision for 2025 revolves around “solidifying her positioning in the U.K., Ireland and the rest of Europe,” as well as making “further inroads” in the U.S. with a North American headline tour booked for September.

CMAT finds herself in fine company on the world stage, with fellow Irish exports Fontaines D.C. and Kneecap having also pushed the needle forward in 2025. All three acts are making music with rich, defiant messaging, an attribute that chimes well with TikTok audiences, where songs can take off if they are attached to a particular story or movement; in this case, “Take A Sexy Picture Of Me” rings true with the collective female experience.

“CMAT is a great example of a real artist who has put in the work and has earned this moment,” AWAL CEO Lonny Olinick tells Billboard U.K. “Across three album campaigns, we have been fortunate to partner with her and do the hard artist development work that AWAL is known for, building her fan base from the ground up. We are all excited to see this powerful record connect with audiences globally.”

Social media star Khaby Lame was detained by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement after being apprehended by authorities on June 6. According to an ICE spokesperson, Lame was granted a “voluntary departure” and has left the United States. The viral TikTok sensation’s Instagram Story showed him in Brazil as of Monday (June 9). The […]

Khaby Lame, the most-followed personality on the popular TikTok social media platform, was detained by ICE officials at the Harry Reid International Airport in Las Vegas, Nevada, last Friday (June 6). According to ICE, Khaby Lame has since left the United States and has not made any public statements regarding the stop by the agency, and a MAGA influencer is claiming credit.

In a report from the AFP, Khaby Lame, 25, was detained by ICE at the airport, with officials citing immigration violation for the stop.

“US Immigration and Customs Enforcement detained Seringe Khabane Lame, 25, a citizen of Italy, June 6, at the Harry Reid International Airport, Las Vegas, Nevada for immigration violations,” according to a statement that spokespeople for ICE gave to the AFP.

Khaby Lame catapulted to fame on TikTok for his silent videos and trademark palms-up gesture at the camera, garnering Lame 16.2 million followers on the TikTok platform. Lame has also leveraged his TikTok fame to establish brand deals outside the platform.

Bo Loundon, a rising MAGA influencer whose feed is replete with attacks on anyone that he perceives as a threat to President Donald Trump’s vision of America, claimed that he has worked alongside the Department of Homeland Security to have Lame detained.

“BREAKING: Far-left ILLEGAL ALIEN TikToker Khaby Lame was just ARRESTED and is now in ICE custody under President Trump,” Loudon tweeted on Friday. “I discovered he was an illegal who overstayed an invalid VISA, evaded taxes, and I personally took action to have him deported. No one is above the law!”

Loudon also shared an X post sharing a similar statement to the one given to the AFP. However, it does not confirm an arrest, and Lame was granted voluntary departure on June 6. It does appear that Loudon’s claim of an arrest was largely exaggerated. We also searched ICE’s arrest database, and it did not turn up any results on Lame.

On X, the reactions to Khaby Lame’s arrest and Bo Loudon’s alleged involvement, with some users calling Loudon’s claims false, have turned up. We’ve got them listed below.

—

Photo: Getty

HipHopWired Featured Video

CLOSE

True to her name, Mariah the Scientist’s songs are often the result of several months, and sometimes years, spent combining different elements of choruses and verses until finding the right mixture. But when it came time for the 27-year-old to unveil her latest single, the sultry “Burning Blue,” the R&B singer-songwriter was at a crossroads. So, she experimented with her promotional strategy, too — and achieved the desired momentum.

“Mariah felt she was in a space between treating [music] like a hobby and this being her career,” recalls Morgan Buckles, the artist’s sister and manager. And so, they crafted a curated, monthlong rollout — filled with snippets, TikTok posts encouraging fan interaction and various live performances — that helped the song go viral even before its early May arrival. Upon its release, Mariah the Scientist scored her first solo Billboard Hot 100 entry and breakthrough hit.

Trending on Billboard

Mariah Amani Buckles grew up in Atlanta, singing from an early age. She attended St. John’s University in New York and studied biology, but ultimately dropped out to pursue music. Her self-released debut EP, To Die For, arrived in 2018, after which she signed to RCA Records and Tory Lanez’s One Umbrella label. She stayed in those deals until 2022 — releasing albums Master and Ry Ry World in 2019 and 2021, respectively — before leaving to continue as an independent artist.

“Over time, you start realizing [people] want you to change things,” Mariah says of her start in the industry. “Everybody wants to control your art. I don’t want to argue with you about what I want, because if we don’t want the same things, I’ll just go find somebody who does.”

Mariah the Scientist

Carl Chisolm

In 2023, after six months as an independent artist, Mariah signed a joint venture deal with Epic Records and released her third album, To Be Eaten Alive, which became her first to reach the Billboard 200. She then made two Hot 100 appearances as a featured artist in early 2024, on “IDGAF” with Tee Grizzley and Chris Brown and “Dark Days” with 21 Savage.

“Burning Blue” marks Mariah’s first release of 2025 — and first new music since boyfriend Young Thug’s release from jail following his bombshell YSL RICO trial. The song takes inspiration from Purple Rain-era Prince balladry with booming drums and warbling bass — and Mariah admits that the Jetski Purp-produced beat on YouTube (originally titled “Blue Flame”) likely influenced some lyrics, too. She initially recorded part of the track over an unofficial MP3 rip, but after Purp caught wind of it and learned his girlfriend was a fan, he gave Mariah the beat. Mariah then looped in Nineteen85 (Drake, Nicki Minaj, Khalid) to flesh out the production.

“I [recorded the first part of ‘Burning Blue’] in the first room I recorded in when I first started making music in Atlanta,” Mariah says. “I don’t want to say it was a throwaway, but it was casual. I wrote some of it, and then I put it to the side.”

Once Epic A&R executive Jennifer Raymond heard the in-progress track, she insisted on its completion enough that Mariah and her collaborators convened in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, in February to finish the song. By that point, they sensed something special. Mariah shared a low-quality snippet on Instagram, but Morgan — who joined as a tour manager in 2022 — knew a more polished presentation was needed to reach its full potential.

Morgan Buckles (left) and Mariah the Scientist photographed May 20, 2025 in New York.

Carl Chisolm

Morgan eyed Billboard’s Women in Music event in late March as the launchpad for the “Burning Blue” campaign. Though Mariah wasn’t performing or presenting at the event, Morgan wanted to take advantage of her already being in glam to shoot a flashier teaser than Mariah’s initial IG story, which didn’t even show her face.

The two decided on a behind-the-scenes, pre-red carpet clip soundtracked by a studio-quality snippet of “Burning Blue.” Posted on April 1, that clip showcased its downtempo chorus and Mariah’s silky vocal and has since amassed more than two million views, with designer Jean Paul Gaultier’s official TikTok account sharing the video to its feed. Ten days later, Morgan advised Mariah to share another TikTok, this time with an explicit call to action encouraging fans to use the song in their own posts and teasing that she “might have a surprise” for fans with enough interaction.

Mariah then debuted the song live on April 19 during a set at Howard University — a smart exclusive for her core audience — as anticipation for the song continued to build. Two weeks later, “Burning Blue” hit digital service providers on May 2, further fueled by a Claire Bishara-helmed video on May 8 that has over 7 million YouTube views.

“We’re at the point where opportunity meets preparation,” Morgan reflects of the concerted but not overbearing promotional approach. “[To Be Eaten Alive] happened so fast, I didn’t even know what ‘working’ a project meant. This time, I studied other artists’ rollouts to figure out how to make this campaign personal to her.”

“Burning Blue” debuted at No. 25 on the Billboard Hot 100 dated May 17, marking Mariah’s first time in the top 40. Following its TikTok-fueled debut, the song has shown legs at radio too, entering Rhythmic Airplay, R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay and Mainstream R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay — to which Morgan credits Epic’s radio team, spearheaded by Traci Adams and Dontay Thompson. “[The song] ended up going to radio a week earlier [than scheduled] because Dontay was like, ‘If y’all like this song so much, then play it!,’ and they did,” Morgan jokes.

With “Burning Blue” proving to be a robust start to an exciting new chapter, Mariah has a bona fide hit to start the summer as she prepares to unleash her new project, due before the fall. She recently performed the track on Jimmy Kimmel Live! and will have the opportunity to fan the song’s flames in front of festival audiences including Governors Ball in June and Lollapalooza in August. But as her following continues to heat up, Mariah’s mindset is as cool as ever.

“I’ll take what I can get,” Mariah says. “As long as I can use my platform to help people feel included or understood, I’m good.”

Mariah the Scientist

Carl Chisolm

A version of this story appears in the June 7, 2025, issue of Billboard.

All products and services featured are independently chosen by editors. However, Billboard may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links, and the retailer may receive certain auditable data for accounting purposes.

Taylor Swift often serves fans a masterclass in style. Over the years, the “Blank Space” singer has turned some memorable looks, giving fans ample outfit inspo.

Recent data gathered by Kaiia pointed to Swift as the celebrity with the most-copied style on TikTok. Boasting 32.5 million followers on the app, Swift has amassed over 22,410 hashtags dedicated to her fashion game alone. Other celebs following suit with the most fashion-related hashtags include Kendall Jenner, Sofia Richie, Ariana Grande, Kylie Jenner and Rihanna.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

For those looking to dress like Swift, we’ve compiled a few pieces that might fit the bill, including Swift-inspired boots, corset tops, slacks and dresses from top brands like Vince Camuto, Reformation, Amazon, Zara and Aritzia and more.

Trending on Billboard

Floerns Women’s Square Neck Sleeveless Corset Denim Top

$26.41

$27.99

6% off

A structured denim corset top.

This denim corset top from Amazon is almost a perfect match to the corsetted tops Swift has worn in the past. The Floerns piece features a unique square neckline accompanied by a cropped asymmetrical hem and a zip-up closure on the back. This corset is made of a comfortable stretchy fabric with boning that offers the garment structure.

Vince Camuto Leila Boots

$95.53

$239

60% off

Burgundy knee-high leather boots with block heels.

From knee-high to thigh-high, Swift has worn burgundy booties often, hailing from brands like Giuseppe Zanotti and & Other Stories. These Vince Camuto Leila silhouettes are extremely similar to those aforementioned styles, retailing for $95.53 at Zappos. These sleek boots also feature a zippered interior closure and elasticized goring that improves fit and comfort.

Urban Outfitters Glamorous Brown Plaid Tie-Front Mini Dress

$19.95

$95.00

79% off

A brown and blue plaid dress with ties on the front.

The Glamorous Brown Plaid Tie-Front mini dress — along with coming right out of Swift’s Folklore era — is playful, capitalizing on the bow trend that absolutely swept the fashion landscape in 2024. Bow accents fastened to the front offer textural interest, while the blue and brown plaid print and puffy sleeves set the dress apart from anything similar on the market now. This print, paired with the flirty, cottagecore silhouette, is extremely unique. Plus the $19.95 price tag is hard to beat.

Reformation James Relaxed Blazer in Brown Herringbone

A grayish brown herringbone blazer in an oversized style.

Blazers are a staple for most, but nobody wears them quite as well as Swift does. We think the singer would adore Reformation’s James Relaxed Blazer in “Brown Herringbone,” given its striking similarity to silhouettes she’s worn in the past. This neutral moment matches the “Love Story” singer’s off-duty fashions.

Lululemon High-Rise Pleated Tennis Skirt

A white high-waisted pleated tennis skirt.

Lululemon’s High-Rise Pleated Tennis Skirt is totally Swift-approved — the silhouette is comparable to styles she’s worn in the past that mix sporty and dressy elements. Retailing for $68.00, this skirt is high-waisted for a flattering fit, accompanied by textural pleating throughout that creates movement and dimension. The monochrome white colorway is ideal for styling, given how versatile the hue is. If the colorway isn’t your thing, Lululemon’s High-Rise Pleated Tennis Skirt also comes in True Navy.

Zara Basic Crewneck Sweatshirt

A unisex deep blue oversized crewneck.

The Zara basic is made of a blend of ultra-plush cotton and polyester that makes you feel like you’re being blanketed in an inviting warmth. Whether you’re dressing this down with sweats or wearing it more formal with tailored slacks, the styling possibilities for this piece are endless.

Aritzia The Effortless Pant in Nomad Taupe

Taupe wide-leg pants with pleated accents.

Great for work or a night out, Aritzia’s The Effortless Pant trousers are totally up Swift’s alley. It comes in a neutral taupe colorway, constructed in a tailored but relaxed fashion that gives the wearer room to explore a variety of styling options both casual and formal. These pants are a go-with-anything kind of style you’ll want to have in your closet.

Zara Oversized Poplin Shirt

An oversized poplin button-down shirt in blue and white.

The blue and white striping of this Zara button-down is visually appealing, leaning much more playful than a simple white tee. Long batwing sleeves create dimension and playfulness, giving way to your standard front patch pocket and button closures. Slouchy fits like these are effortlessly chic, especially when worn with jeans and sneakers or equally breezy shorts. Swift has worn button-downs like these for years.

Abercrombie & Fitch Stretch Sequin Micro Short

Black sequin micro shorts.

Looking back on some of Swift’s most iconic stage looks, we’ve picked these sparkly micro shorts from Abercrombie & Fitch. The itty bitty pair is made of black stretch fabric that molds flatteringly to the body. This style is quintessential party material: eye-catching, form-fitted and cheeky. Swift has worn styles like these with oversized hoodies or vibrant flannels, especially during her Reputation era.

Latasa Women’s Red Platform Chunky Mary Janes Pumps

Patent red leather Mary Jane pumps with block heels.

Latasa’s Women’s Red Platform Chunky Mary Janes Pumps gives us flashbacks to Swift’s Red era. These days, the singer has adopted Mary Janes into her modern wardrobe, opting for platform styles that update the otherwise retro silhouette. This pair ticks all the right boxes for Swift’s modern-day footwear formula, with platform soles for height, along with block heels standing at 3.5 inches. The red hue is a nice touch, something we can see Swift, and her fans, wearing time and time again.

“A Million Colors” by Vinih Pray has become the first-known AI-generated song to hit the TikTok charts. Currently sitting at No. 44 on the TikTok Viral 50, the doo-wop inspired song was generated using the popular AI music platform Suno, the company has confirmed.

While this marks the first AI-generated song to hit the TikTok charts, there was one previous song on the TikTok charts that was human-made but contained an AI-generated sample. In the summer of 2024, “U My Everything” by Sexyy Redd, featuring Drake — which sampled the AI-generated song “BBL Drizzy” — peaked at No. 2 on the TikTok Top 50, but the most common sound clip used from “U My Everything” did not feature that sample.

With over 371,700 creates on TikTok, 819,745 streams on Spotify, 161,000 views on YouTube, “A Million Colors” sounds so realistic that it has fooled a number of unsuspecting users. One of the most popular celebrities on the platform, Kylie Jenner, recently posted a makeup tutorial with the AI-generated song in the background, earning her 1.5 million likes.

Trending on Billboard

Some TikTok users, however, have started catching on. On “A Million Colors” sound page, a number of videos are being made by users to call out its use of AI. This likely traces back to a popular video by @americangorls, who wrote in a post on May 10 “this song having hundreds of thousands of uses and I haven’t seen anyone talking ab the fact that this is 100% ai is freaking me out a little. am i crazy[?]”

According to his Spotify bio, Pray, the artist who posted “A Million Colors,” was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and is “making waves in the Brazilian music scene,” and that “in addition to his solo career, [Pray] has collaborated with several renowned artists,” although it does not state who those artists are. He releases music at a quick pace — since he started posting to the page in April 2024, Pray has released over 110 songs to Spotify and other platforms in a variety of languages, including Korean, English, Portuguese and Mandarin. Most songs contain different voices, and it is unclear if any are using Pray’s own voice. It is also unclear how many of these songs are AI-generated or human-made.

Pray and TikTok have not replied to Billboard’s request for comment.

With “A Million Colors,” Pray positions himself among a growing class of AI music content creators on the internet. King Willonius, the artist who used Udio to generate “BBL Drizzy” posts a number of AI-generated parody songs to his 56,000 followers on Instagram. Another popular AI music poster, AI For the Culture, has garnered 150,000 subscribers on YouTube for his work, which includes AI-generated period music, paired with an AI image and a fictional artist bio to humanize the track. One of his songs, “Turn On The Lights” — which used AI to reimagine a Future’s “Turn On The Lights” as 1970s soul — was sampled in JPEGMAFIA‘s “either on or off the drugs” last year.

TikTok launched a new tool on Tuesday (June 3) to help artists understand the way their music percolates through the app’s ecosystem. TikTok for Artists will provide acts with daily information about how their songs are used and which tracks are driving the most engagement. On top of that, the dashboard furnishes artists with information […]

Who knew Gypsy Rose Blanchard was a Cardi B fan? The Prison Confessions of Gypsy Rose Blanchard subject took to TikTok this week to share a “Toot It Up” dance video — set to Pardison Fontaine and Cardi’s February single “Toot It Up” — admirably tackling the viral choreography, including dribbling an invisible basketball between […]

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio