tiktok

All products and services featured are independently chosen by editors. However, Billboard may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links, and the retailer may receive certain auditable data for accounting purposes.

Trending on Billboard

Owala is always at the scene of a viral moment. The brand’s bottles are a hot product, especially as we get into the holiday gifting season.

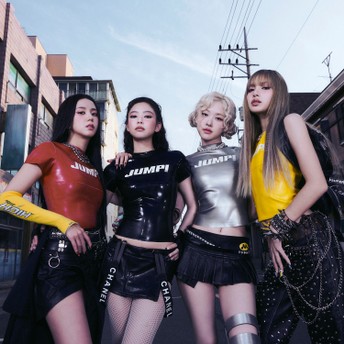

The brand is just one of many popular drinkware brands capitalizing off of viral marketing and TikTok fame from Stanley and Hydro Flask to Bink. Owala boasts a ton of fans on TikTok including a few famous musicians like Hilary Duff and even BLACKPINK’s Rose.

Owala’s most popular silhouettes are the FreeSip, an insulated bottle with a straw and a chug lid design that allows users to either sip through the straw or take a larger drink directly from the spout. While the design is a popular draw, the brand finds its most success through its offered colorways, of which there are a ton.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

The most popular of the bunch as of late? Black Cherry colorway, a deep, rich red that resembles a juicy cherry just plucked from a bushel. The colorway, in their popular FreeSip Twist model, is available on Amazon and the best part? It’s currently on sale for just $23.99, so you won’t have to spend a pretty penny to snag the on-trend bottle.

Owala FreeSip Twist Insulated Stainless Steel Water Bottle with Straw

$23.99

$29.99

20% off

A cherry red Owala FreeSip Twist water bottle.

If you don’t think the hype for this colorway is real, just look at TikTok. The search for “Black Cherry Owala” on the app has thousands of videos being posted every day. One user commented, “Okay, this convinced me…I think black cherry needs to be my first Owala,” while another raved, “I’ve never been a Stanley or Owala girly, I just drink water bottles lol but I HAD to buy this one. LOVE the color.”

While the color is cute, Owala bottles are also raved about for their durability and insulation properties that keep 24oz of cold drinks cool and hot drinks hot for hours at a time. The FreeSip is also leak-proof, so it can withstand a tumble without spilling a single drop. Great to take on the go or use at home, this bottle is definitely one you’ll be seeing on Christmas lists this year. If you’re not a fan of the Twist model, the brand’s Amazon storefront also carries the regular FreeSip model in Black Cherry as well for $29.94.

Owala FreeSip Insulated Stainless Steel Water Bottle with Straw, BPA-Free Sports Water Bottle, Great for Travel, 24 Oz, Black Cherry

A FreeSip Owala in Black Cherry.

The FreeSip is in high-demand, especially as people go searching for it to gift to that special someone this holiday season. The price on the best-seller is usually $30 and sometimes even more if it’s an in-demand colorway. You’ll want to snag the bottle at this price while it lasts, because it’ll be gone if you wait too long. Just trust us.

‘Wicked’ FreeSip Insulated Stainless Steel Water Bottle with Straw 32oz

A Wicked-themed Owala FreeSip bottle.

If you really want to get into the Owala mania, the brand just launched a Wicked: For Good collaboration in pink and green, naturally. Both themed bottles are available for preorder now on Owala’s Amazon storefront and retail for $39.99.

Trending on Billboard

Over her 20-plus-year career, Tracy Gardner has seen her fair share of technological disruptions in the music business. “I started right when illegal downloads took over,” she says of her entry into the industry as an intern at what was then Warner Bros. Records (now Warner Records).

As TikTok’s global head of music business development — a position she has held since February — Gardner is now running point for the biggest disruptor of the industry over the last five years. The Brooklyn Law graduate, whom ByteDance recruited in 2019 after six years in the legal affairs and business development departments at Warner Music Group, took over from Ole Obermann — whom she also worked with at WMG — when he departed for Apple Music.

Related

In her new role as the platform’s chief liaison with the music industry, Gardner oversees deals with labels, publishers and the TikTok commercial music library and works closely with the platform’s strategy, finance, artist services, product and ad sales teams.

Her promotion comes at a fitful moment for TikTok, as ByteDance and the Trump administration are reportedly finalizing a deal that would result in a consortium of U.S. investors acquiring a majority stake in the app. Gardner was not able to comment on that process or how it might affect her division. But in this interview — her first since assuming her current role — she asserts that nearly two years after Universal Music Group temporarily pulled its artists’ music from TikTok over a breakdown in licensing negotiations, and the social media platform shifted label licensing away from Merlin, which licenses digital companies on behalf of over 30,000 indie labels and distributors, “We’re in a great place with the music industry. It’s a dynamic partnership that, as TikTok evolves quickly, has an impact on how we’re looking at deals, how we work with partners and what they want to get from a partnership with us.”

At Warner, you were on the other side of the negotiating table with ByteDance. How did that experience affect how you conduct your job now?

Mainly, it was great to come from the perspective of being at a label and a rights holder. [TikTok] was still relatively new when I got there, and we had to build the infrastructure and collaborate with other teams at ByteDance. A lot of our music team came over from either other DSPs [digital service providers] or labels, so there was a very good base to help the product teams, who don’t have music experience, understand what these rights holders expect from tech partners and what their artists are looking for.

What did you learn from watching Ole Obermann?

Ole and I worked together at Warner. Often people in business development [at music companies] come from one of two paths: f inancial or legal backgrounds. I was fortunate that Ole came from a more numbers- based, financial background, whereas mine was legal. He forced me out of my comfort zone. I wanted to look at the term sheet, and he told me, “You have to focus on the numbers. The numbers don’t lie.” Then we both moved to TikTok, and he [built] a great infrastructure of how the team operates, how we present budgets and how we work with senior management.

Related

How have you tailored your current role to your perspective and experience?

Ole was overseeing both recorded music and publishing, while I was more in day-to-day operations on the recorded-music side working with artists. So when I took on this new job, I said, “Why don’t we apply the best practices we have for artists to songwriters?” One thing that we’re particularly proud of is the songwriter feature we launched earlier this year [enabling songwriters to tag songs they’ve written in the music tab of their account]. The songwriters are really enjoying being able to step out from behind the curtain and get the acknowledgment that they deserve. We plan to roll that out more broadly.

TikTok increasingly has prioritized e-commerce with the TikTok Shop. How is your team working with artists there?

We are working with the e-commerce teams at the labels as well as our own. One thing we’re seeing is old vinyl sells. Even though people don’t have record players, they view these albums as collectibles. We also see great success when an artist does a livestream. We did one with Lizzo that was quite successful and one with the Jonas Brothers.

TikTok has hosted a number of intimate pop-up events recently for artists’ top fans. Ones with Miley Cyrus and Ed Sheeran come to mind immediately. This is an interesting move to me because you are a social media platform. You want to engage fans online. Why did you want to take people off their phones and get them outside with artists?

Music discovery starts on TikTok — discovery, promotion and fandom grows here, and we view it as a flywheel. After discovering a song, we then help to promote it with some of the campaigns that we do, then we tie that to the “Add to Music App” function so that you can listen on your streaming service. We’re see that what we do moves the needle on streaming, which then leads to charts, which then leads to increased fandom.

We thought that there would be a great opportunity to bring this to real life, to invite the fans that have the greatest engagement with an artist on TikTok to come see the artist in person, even if it does mean going off the platform for a bit. What I thought was beautiful about the Miley event at Chateau Marmont, was that the people there were so impassioned that they started posting so much about it. Even though I wasn’t there, they made me feel like I’d actually experienced it. Right now, we’re finding a way to create joyful intimate moments and creating them in a way that encourages fans to film and to bring them back onto TikTok.

Related

After a song goes viral on TikTok, it often ends up doing really well on streaming services. For a while, TikTok was building its own streaming service, TikTok Music. Why was it shut down last year?

It was just a decision of priorities. We were trying to grow it for quite some time, and the decision was made: “You know what? Out of all the things we’re doing, this is not succeeding at the level we want. Let’s focus on other areas.” It was an awesome service and it really tied in all the great parts of TikTok, but it was just a decision by management.

TikTok recently let go about 15 people from the U.S. and Latin American music teams, and layoffs are forthcoming in the United Kingdom. Some are interpreting this as a sign that the company is backing away from its partnerships with the music business.

As so many other big companies have recently done — Amazon announced a big round of layoffs, for instance — organizational changes are due to changes in structural needs. Companies can grow very quickly and then must reassess what’s best for them. There is definitely no change in the priority around artist services and artist relations. For us, it’s business as usual.

How are you reassuring the music industry that you remain committed to the partnerships and plans you already made?

We’re telling them it’s business as usual, and our valued industry partners remain the highest priority. We just want to focus more on the core priorities for artists and songwriters to help drive the value on the platform.

How is TikTok ensuring artists have safeguards against artificial intelligence-generated deepfakes?

We ask that users tag anything that’s AI-created. Aside from that, I don’t think the industry has a quick solution right now to identify those and take them down. If someone notifies us, our trust and safety team will take them down if needed. But it is a very interesting time right now.

Related

AI-generated songs have appeared on the TikTok and Billboard charts. Are you pursuing any policies that would bar AI music on your platform and charts?

It’s uncharted territory. Even with U.S. Copyright Office guidance that works must have sufficient human contribution to be protected, what does that mean? There’s such a wide span from a song being totally created by AI to one that’s created by a human with just one or two AI contributions. How do we decide when it’s such a gray zone? So I don’t think we’ve made a decision on that yet, and I don’t think a lot of the DSPs have either.

If AI-generated music starts performing well on TikTok, could it diminish the leverage rights holders have in negotiations with you?

I don’t think it would have any impact. We’re all aware that AI music is out there, and some exceptions have risen on the charts, but it would not at all impact the value that we see in our partners and how our deals with them are structured.

What are some best practices for artists seeking to gain an audience on TikTok?

The beauty of it is that any song has a chance to go viral. It just depends on how the billions of people on the platform react to the song. Oftentimes, I’m asked, “Do you have to be really leaned in?” It depends. A great example is Connie Francis. Her song “Pretty Little Baby” blew up this year. She wasn’t on the platform at the time. Eventually she did get on, which was great, but this music resonated [on its own].

Brenay Kennard, a popular social media figure who amassed millions of followers, was ordered to pay $1.75 million to the ex-wife of her manager, who was married to the woman before his involvement with Kennard. Known as @lifeofbrenay across her socials, Brenay Kennard was accused of splitting up the marriage of her marriage by the ex-wife, citing criminal conversation and alienation of affection.

Raleigh outlet WRAL reports that Akira Montague, the ex-wife of Brenay Kennard’s current manager, Tim Montague, accused Kennard of seducing her husband and ending their seven-year union. Under North Carolina’s “alienation of affection” law, a spouse has the legal right to sue an individual they believe led to the end of a marriage. Ms. Montague said that the affair caused her mental anguish and took her husband away from their children.

Kennard defiantly fired back at Ms. Montague, saying that the marriage was essentially over and that the ex-wife gave her blessing for them to move forward. It was also rumored online that Kennard was married to another man during the affair.

Love Hip-Hop Wired? Get more! Join the Hip-Hop Wired Newsletter

We care about your data. See our privacy policy.

Trending on Billboard

iHeartMedia struck a new partnership with TikTok that will see TikTok creators featured in long-form audio and video content across iHeart platforms, it was announced on Monday (Nov. 10).

The deal includes the launch of the TikTok Podcast Network, a slate of up to 25 podcasts from TikTok creators. Under the agreement, iHeartMedia will open co-branded podcast studios in Los Angeles, New York and Atlanta that will be set up for both audio and video content. The podcasts will be distributed by iHeartPodcasts and made available on the iHeartRadio app and other podcast platforms. Listeners will also be able to watch highlights and clips from the podcasts on TikTok.

Related

Another component of the deal is TikTok Radio, which will pair TikTok creators and established iHeartRadio personalities on iHeart broadcast radio stations across the U.S. and digitally on iHeartRadio. According to a press release, “TikTok Radio will feature not only TikTok’s hottest new songs, but also trend-driven storytelling and emotional context behind the music,” with segments including Behind-the-Charts, New Music Fridays and On the Verge.

iHeart and TikTok will additionally team up on iHeart events like the iHeartRadio Music Festival and iHeartRadio Jingle Ball, “empowering brands to activate with a dynamic network of content creators,” according to the release.

More details on the partnership will be announced in the coming months.

“This partnership connects TikTok’s cultural energy and creator community with the unmatched scale and reach of iHeartMedia,” said Rich Bressler, president, COO and CFO of iHeartMedia, in a statement. “We’re giving creators access to the biggest audio platforms in America — creating new ways to tell stories, entertain, and build deeper connections with fans. Together, we’re combining our vast networks to deliver relevant content on a massive scale. It’s a win for creators, fans, and brands alike.”

Related

“At TikTok, empowering creativity and connecting communities are at the heart of everything we do,” added Dan Page, global head of media and licensing partnerships at TikTok. “This partnership with iHeartMedia opens up exciting new opportunities for creators and brands to reach wider audiences, collaborate across platforms and extend their creativity beyond the TikTok platform. Together, we’re amplifying the connection between artists, creators and our community through the shared power of cross platform storytelling.”

TikTok and iHeart kicked off their partnership earlier this year with the singing competition Next up: Live Music, which was hosted exclusively on TikTok LIVE.

Trending on Billboard

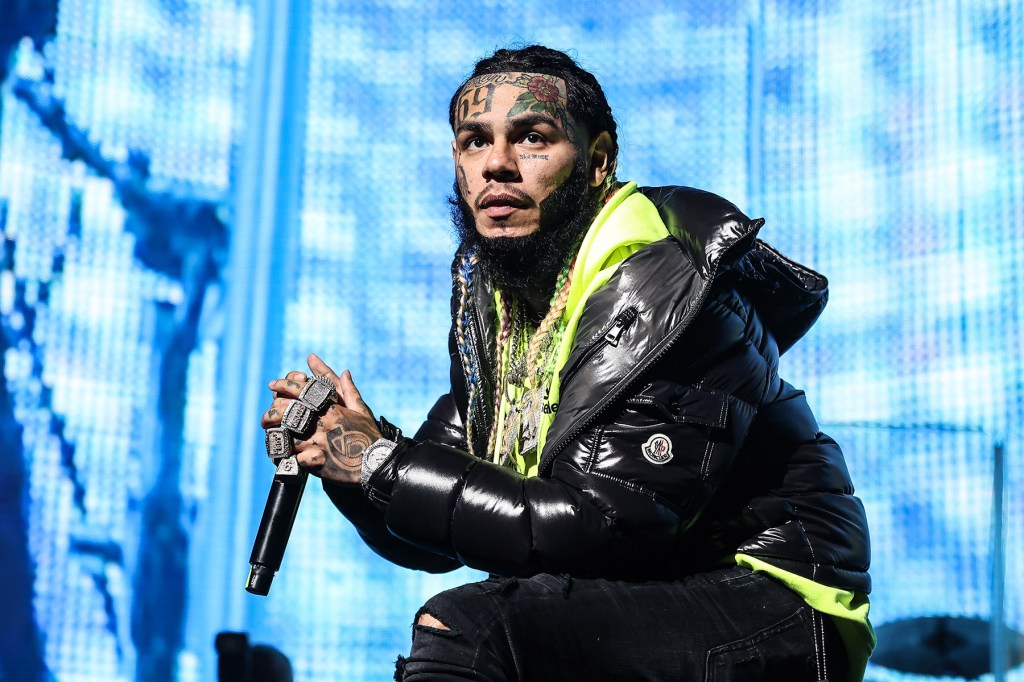

6ix9ine claims to be the original content creator, suggesting that people dismiss his influence simply because they are haters.

During his appearance on Adin Ross’ Kick channel on Wednesday, the rainbow-haired rapper reflected on his rise to fame, stating that his breakout moments preceded the invention of TikTok. He argued that if the app had existed during his tumultuous ascent in 2018, he would have dominated the platform.

“In 2018, there was no TikTok,” he said at the 40-minute mark. “Let me get this point across, and maybe y’all say I’m reaching, but this is what I truly believe. … I walked, I went to jail, I entertained you guys with real-life crimes. I was out there putting my life on the line so you guys could run. When Vine was a thing, remember? Instagram. I was the original content creator. I know people don’t like me. It’s the right message, wrong messenger. But these is facts.”

The rapper recalled some of his most unforgettable viral stunts during his rise, including running up a hill with an AK-47. He mentioned prominent streamers like Ross, IShowSpeed and Kai Cenat, claiming they owe some of their success to his pioneering style.

“Y’all remember that?” he said. “Y’all was in high school. I walked so y’all could run, so streamers could run. … My Instagram views and numbers were through the roof. I think I was meant to be a streamer because I’m not faking nothing. I’m just charismatic, and when I’m wrong, I’m wrong. I’m human at the end of the day. But I respect what you do.”

He continued to emphasize how his candidness shaped perceptions of him: “People don’t like me because they can’t control my mouth… and they’re like, ‘Damn, he’s too right.’ I’m not right about everything, because I’m human… I fed families. I’ve fed many families. I’ve created a lot of movements. But because I’m 6ix9ine, people are like, ‘Nah, nah, nah.’”

Check out the full stream below.

Trending on Billboard

Some Taylor Swift fans are up in arms over a video on the official White House TikTok account set to “The Fate of Ophelia” — and many of them are encouraging the pop superstar to take legal action against President Donald Trump.

The Monday (Nov. 3) TikTok video pairs Swift’s The Life of the Showgirl lead single — currently in its fourth week at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 — with images of Trump and his associates. One frame shows Trump’s mug shot while Swift sings, “Don’t care where the hell you’ve been.” The video ends with a photo of the president scooping McDonald’s French fries under a slightly altered lyric reading, “The fate of America.”

Related

Swift has not commented on the post, but it’s unlikely that she’s happy about it. Historically, the star has not pledged her allegiance to Trump’s team; she’s only endorsed Democrats, including Kamala Harris in the 2024 election, and Trump, in turn, has insulted Swift repeatedly, including by posting “I HATE TAYLOR SWIFT” after the Harris endorsement.

In the TikTok comments, some Swifties are putting on their lawyer hats. “TAYLOR SWIFT SUE THEM FOR USING YOUR SONG!” wrote one. “I would absolutely LOVE if Tay found a way to sue them for this,” wrote another. “One freaking huge lawsuit on the horizon,” another prediction read.

Is the White House’s use of “The Fate of Ophelia” legal? Probably not. While individual TikTok users can soundtrack their videos with pre-cleared songs, commercial entities are required to obtain so-called sync licenses from copyright owners. The White House did not return an inquiry on Tuesday (Nov. 4) as to whether they got a sync license for the post, but given Swift’s public rebukes of Trump, and the fact that the singer is famously protective of her catalog, it’s unlikely that she greenlit such a license.

Related

As Billboard previously reported during Zach Bryan’s public scuffle with the Trump administration over its use of his track “Revival” in an X post, there are a number of legal avenues for artists to take when their songs are used on social media without licenses. Swift’s lawyers could send a cease-and-desist letter to the White House, or they might lodge a formal takedown notice directly with TikTok under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

If these administrative procedures are unsuccessful, Swift could indeed bring a formal lawsuit against the federal government for copyright infringement. She’s no stranger to intellectual property litigation, having both faced copyright claims herself and gone on the legal offense over the years.

However, it’s hard to imagine Swift taking the drastic step of suing the White House. The courts are public by nature, and Swift has a carefully maintained image. This is especially true in the political arena, where the singer’s statements have always been measured (“The choice is yours to make,” she told fans in her post endorsing Harris last year).

Related

Swift, therefore, may not want to become publicly embroiled in what would almost certainly be viewed as a partisan legal battle. Nothing is certain, though, and only time will tell.

Swift’s reps did not return a request for comment on the matter.

Back row: Lara Raj, Daniela Avanzini, Sophia Laforteza, Front row: Yoonchae Jeung, Manon Bannerman, Megan Meiyok Skiendiel of Katseye visit the Trü Frü backstage portrait studio at iHeartRadio’s 102.7 KIIS FM Wango Tango concert on May 10, 2025 in Huntington Beach, California.

Sara Jaye/Getty Images for Trü Frü

Trending on Billboard On Wednesday (Oct. 22), around fifteen employees in U.S. and Latin American music roles at TikTok and ByteDance across multiple territories were told their positions were terminated, according to sources close to the matter. Two sources say a number of those impacted will have their accounts on the company’s business management platform, […]

Trending on Billboard

Lizzo is facing a copyright lawsuit over her “I’m Going Til October,” a track she teased on social media to poke fun at Sydney Sweeney’s American Eagle ad controversy but never actually commercially released.

The case, filed Tuesday by a group called GRC Trust, claims that Lizzo’s provocative song (also known as “Good Jeans” in reference to the Sweeney debacle) stole material from an earlier track called “Win or Lose (We Tried),” which appears to have been recorded by the soul singer Sam Dees.

Related

Obtained by Billboard, the lawsuit is light on details – claiming Lizzo’s track “incorporates, interpolates, and samples instrumental and vocal elements” without more specifics. But it pointedly says that reps for the star have “acknowledged” that the materials were used.

The case is notable because Lizzo never formally released the song in question. Though she teased a snippet on TikTok, the star has not included it on any formal release, including her June mixtape My Face Hurts From Smiling. Her long-awaited next studio album, Love in Real Life, was scheduled to drop at some point in 2025 but she said last month she’s unsure if or when it will be released.

Posting a song featuring an uncleared sample on social media would still count as copyright infringement; but the stakes would be lower, because it would be harder to prove that Lizzo made substantial profits without actually selling the allegedly infringing song. Such pre-release disputes are more typically handled with private negotiations rather than full-blown lawsuits.

In a statement to Billboard, Lizzo’s reps said: “We are surprised that The GRC Trust filed this lawsuit. To be clear, the song has never been commercially released or monetized, and no decision has been made at this time regarding any future commercial release of the song.”

Related

The American Eagle ads, launched in July under the tagline “Sydney Sweeney Has Great Jeans,” sparked criticism that they were an allusion to eugenics and white supremacist ideals. That then prompted a right-wing backlash defending them and mocking the critiques.

In her August video on TikTok, Lizzo can be seen washing a Porsche while wearing a denim top. The clip features a snippet from “Going Til October,” in which the star raps: “No kizzy, he ain’t got no business being with me. Fat ass pretty face with the titties. Bitch, I got good jeans like I’m Sydney.”

While Tuesday’s lawsuit claims that snippet used material from “Win or Lose,” it doesn’t explicitly specify who wrote or recorded that track. But it appears to be the 1995 song recorded by Dees, which repeatedly features the lyric “win or lose we tried.” In an earlier sampling suit against Ye (formerly Kanye West), GRC Trust brought similar infringement allegations over another track by Dees.

The copyright case is the latest legal headache for Lizzo. In 2023, she was hit with a bombshell lawsuit from three former dancers (Arianna Davis, Crystal Williams and Noelle Rodriguez) who claimed they had experienced sexual harassment and a hostile work environment while working for the superstar. The case, which also included allegations of weight-shaming, racial and religious discrimination, remains pending amid a lengthy appeal.

President Donald Trump on Thursday (June 19) signed an executive order to keep TikTok running in the U.S. for another 90 days to give his administration more time to broker a deal to bring the social media platform under American ownership.

Trump disclosed the executive order on the Truth Social platform Thursday morning.

“As he has said many times, President Trump does not want TikTok to go dark. This extension will last 90 days, which the administration will spend working to ensure this deal is closed so that the American people can continue to use TikTok with the assurance that their data is safe and secure,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said in a statement on Tuesday.

It is the third time Trump has extended the deadline. The first one was through an executive order on Jan. 20, his first day in office, after the platform went dark briefly when a national ban — approved by Congress and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court — took effect. The second was in April when White House officials believed they were nearing a deal to spin off TikTok into a new company with U.S. ownership that fell apart after China backed out following Trump’s tariff announcement.

Trending on Billboard

It is not clear how many times Trump can — or will — keep extending the ban as the government continues to try to negotiate a deal for TikTok, which is owned by China’s ByteDance. While there is no clear legal basis for the extensions, so far there have been no legal challenges to fight them. Trump has amassed more than 15 million followers on TikTok since he joined last year, and he has credited the trendsetting platform with helping him gain traction among young voters. He said in January that he has a “warm spot for TikTok.”

“We are grateful for President Trump’s leadership and support in ensuring that TikTok continues to be available for more than 170 million American users and 7.5 million U.S. businesses that rely on the platform as we continue to work with Vice President Vance’s Office,” the company said in a statement.

As the extensions continue, it appears less and less likely that TikTok will be banned in the U.S. any time soon. The decision to keep TikTok alive through an executive order has received some scrutiny, but it has not faced a legal challenge in court — unlike many of Trump’s other executive orders.

Jeremy Goldman, analyst at Emarketer, called TikTok’s U.S situation a “deadline purgatory.”

The whole thing “is starting to feel less like a ticking clock and more like a looped ringtone. This political Groundhog Day is starting to resemble the debt ceiling drama: a recurring threat with no real resolution.”

That’s not stopping TikTok from pushing forward with its platform, Forrester analyst Kelsey Chickering says.

“TikTok’s behavior also indicates they’re confident in their future, as they rolled out new AI video tools at Cannes this week,” Chickering notes. “Smaller players, like Snap, will try to steal share during this ‘uncertain time,’ but they will not succeed because this next round for TikTok isn’t uncertain at all.”

For now, TikTok continues to function for its 170 million users in the U.S., and tech giants Apple, Google and Oracle were persuaded to continue to offer and support the app, on the promise that Trump’s Justice Department would not use the law to seek potentially steep fines against them.

Americans are even more closely divided on what to do about TikTok than they were two years ago.

A recent Pew Research Center survey found that about one-third of Americans said they supported a TikTok ban, down from 50% in March 2023. Roughly one-third said they would oppose a ban, and a similar percentage said they weren’t sure.

Among those who said they supported banning the social media platform, about 8 in 10 cited concerns over users’ data security being at risk as a major factor in their decision, according to the report.

Democratic Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia, vice chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said the Trump administration is once again “flouting the law and ignoring its own national security findings about the risks” posed by a China-controlled TikTok.

“An executive order can’t sidestep the law, but that’s exactly what the president is trying to do,” Warner added.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio