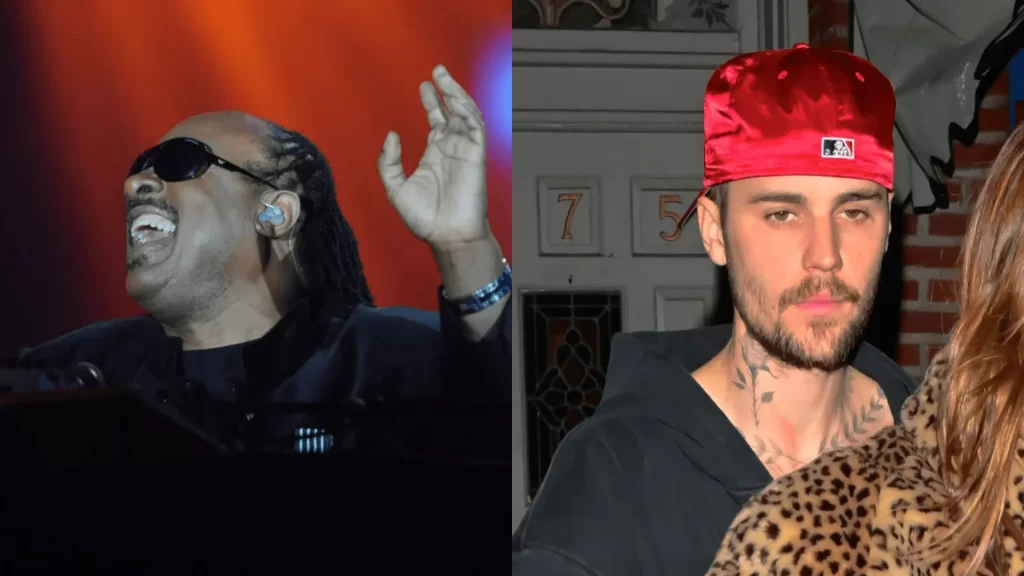

stevie wonder

HipHopWired Featured Video

CLOSE

Source: LIONEL BONAVENTURE/Raymond Hall / Getty

Justin Bieber stirred up controversy yet again, this time for trolling legendary musician Stevie Wonder on social media.

In a now-viral Instagram Story, Bieber posted a screenshot of an unanswered FaceTime call to Stevie Wonder, jokingly captioning it, “This fool never sees my FaceTimes.” While some fans found the joke lighthearted, many felt it was in poor taste, given that Stevie Wonder has been blind since birth. Though likely meant to be humorous, the timing and tone of the post rubbed people the wrong way. Online reactions were mixed; some laughed it off, while others criticized Bieber for being insensitive and using Wonder’s disability as the punchline.

One fan commented, “Even if Stevie could see, I doubt he’d be answering FaceTime from a crash-out king like Justin right now.” The trolling has also reignited concern about Bieber’s mental state. Over the past few weeks, fans have noticed strange behavior and erratic posts from the pop star, sparking speculation that he may be struggling behind the scenes. Many are now calling on Hailey Bieber to check in on him, with comments like, “Where’s Hailey? Someone needs to make sure he’s good,” appearing across platforms.

Related Stories

While Bieber has always walked a line between being goofy and controversial, this latest moment has fans wondering if his trolling is masking deeper issues. Whether it was a harmless joke or something more, one thing is clear—people are paying attention, and not all of it is positive.

HipHopWired Featured Video

Source: Paul Natkin / Getty

The legendary Roberta Flack was laid to rest on Monday (March 10) in New York during a public memorial service that featured words from the Rev. Al Sharpton and other notable figures. Stevie Wonder was on hand for a moving tribute, along with a surprise appearance from Ms. Lauryn Hill and Wyclef Jean.

Roberta Flack passed away on Feb. 24, sparking several responses from entertainers and music lovers from around the world on social media. Flack’s influence and towering legacy were mentioned several times throughout the service, and Rev. Sharpton artfully illustrated the vocalist’s significance in Black music culture, as reported by the Associated Press.

The outlet added in its reporting that Stevie Wonder was a scheduled performer, and other performers, such as Valerie Simpson of Ashford & Simpson fame, took to the stage. Phylicia Rashad, who shared that she first encountered Flack as a young vocalist while attending Howard University, remarked how arresting the singer’s voice was then.

There were also video tributes delivered by Clive Davis, Dionne Warwick, India.Arie, and Alicia Keys, along with remarks delivered by many in attendance in honor of Flack and her lasting legacy.

The appearance of Lauryn Hill and Wyclef Jean was not on the docket, and Hill delivered a speech citing Flack’s influence on her life.

“I adore Ms. Roberta Flack,” Hill said during a speech. “Roberta Flack is legend.”

Hill performed a rendition of “The First Time I Ever Saw Your Face” and then launched into the Fugees’ award-winning cover of “Killing Me Softly With His Song,” with Wonder joining on harmonica and Jean on guitar. Wonder then took to the stage and performed “If It’s Magic” alongside a harpist. Wonder then went to the piano and performed “I Can See the Sun in Late December,” a song he wrote for Flack.

Roberta Flack was 88 at the time of her passing.

Watch the memorial service in full below.

—

Photo: Getty

What is yacht rock? In the new HBO movie, Yacht Rock: A Dockumentary, no one can agree on a definition.

For the comedian Fred Armisen, yacht rock is “a very relaxing feeling.” But for the writer Rob Tannenbaum, yacht rock is a space where singers “could declare not just your sensitivity but your torment at how sensitive you are, your sense of being ravaged by having feelings.” He calls this “fairly unique to yacht rock,” which would be true if soul music did not exist.

How about another, more specific, definition: “One way to know if you’re listening to yacht rock is [if you hear] the sound of Michael McDonald’s voice,” according to Alex Pappademas, author of Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors From the Songs of Steely Dan. Then again, David Pack, lead singer of the band Ambrosia, calls McDonald’s style “progressive R&B pop,” while Questlove describes yacht rock as “utility more than it is music.”

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

This all begs the question: If yacht rock is such a vague label, what makes it worth using?

J.D. Ryznar and Steve Huey helped coin this imprecise term in their 2005 mockumentary series Yacht Rock, long after the music it attempted to brand was out of style. Each episode traced the activities of goofy, fictionalized versions of McDonald, his contemporaries, and his collaborators — Hall & Oates love to dunk on “smooth music,” while Kenny Loggins’ character says pompous things like, “when a friend is drowning in a sea of sadness, you don’t just toss them a life vest, you swim one over to them.”

Trending on Billboard

As the yacht rock label caught on, it gave a set of younger listeners a way to explore and maybe embrace — even if ironically — music that had become a kind of cultural shorthand for uncool, the target of mainstream jibes in Family Guy and The 40-Year-Old Virgin. “For a long time, I thought Steely Dan, man, that’s just music for dorks and weirdos,” the critic Amanda Petrusich says in A Dockumentary. “You come to it jokingly,” Pappademas adds, discussing yacht rock. “But then you suddenly find yourself appreciating it sincerely.”

As yacht rock DJ nights and streaming playlists proliferated, this elevated the artists most closely associated with the style, helping to extend their careers. “I fully expected to be totally forgotten by the end of the 1980s,” McDonald says in A Dockumentary. Instead, the film shows him and Loggins collaborating with the bass virtuoso Thundercat in 2017 and performing at Coachella — one of the world’s most prominent stages.

That said: While the yacht rock label gave some artists a boost, it actually masks the lineage of the music it purports to describe. It serves as camouflage, rather than providing clarity.

Most notably, the term obscures the sizable debt that these records owe to contemporaneous Black music. Many of the tracks associated with the style are steeped in the language of 1970s R&B, conversant with Marvin Gaye‘s intricate, tortured funk, immaculate Quincy Jones productions, and the airy, wrenching ballads Earth, Wind & Fire and the Isley Brothers scattered like birdseed across the second half of the Seventies.

The dialog was facilitated by session musicians who moved easily between worlds. Chuck Rainey played bass with Steely Dan but also appeared on Gaye’s I Want You and Cheryl Lynn’s Cheryl Lynn. Greg Phillinganes handled keyboards for McDonald and Leo Sayer as well as Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder. Horn player and arranger Jerry Hey hopped from Boz Scaggs and Michael Franks to Teena Marie and Janet Jackson.

A Dockumentary nods to yacht rock’s lineage. “Yacht rock is associated with white groups and white songwriters and producers, but I know more Black yacht rock than I do traditional yacht rock,” Questlove says, pointing to Al Jarreau, the Pointer Sisters’ “Slow Hand,” and George Benson’s “Turn Your Love Around.” That music doesn’t get much play in the typical yacht rock conversation, though — or in A Dockumentary.

What does it mean that one of the strands of white music that was most in touch with the Black music of the 1970s was reclaimed largely as a joke, even if it’s an affectionate one? Armisen believes that “there’s nothing greater, in a way, for any genre to be joked about, because it means that it’s relevant.”

This may be a sensible perspective for a comedian. It’s not surprising, though, that the subjects of the wisecracks don’t always feel the same way. “At first, I felt a little insulted, like we were being made fun of,” says Loggins. “But I began to see that it was also a kind of ass-backwards way to honor us.”

Unlike Loggins, Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen hasn’t reached this stage of acceptance. When the documentary’s director asked him about yacht rock, Fagen cursed at him and hung up the phone, an exchange that was recorded and included in the film. Steely Dan’s longtime producer Gary Katz expressed a similar disinterest in the yacht rock label — albeit using less-colorful language — this summer during an interview with the music manager Scott Barkham in Brooklyn Bridge Park.

It’s not unusual for artists to express hostility towards genre terms. In fact, they are constantly saying they don’t want to be “pigeonholed” or “put in a box.” When the critic Kelefa Sanneh published Major Labels, a book-length defense of musical genre, in 2021, he wrote that artists “hate being labeled. And they think more about the rules they break than about the ones they follow.”

There is certainly a case to be made against the whole idea of summing up a large body of art in a word or two. The result is, all too often, genre descriptors that are either all-encompassingly vague or simply inaccurate. Some labels, however, are at least fairly neutral — “post-punk,” “house music.” Some, on the other hand, have negative connotations, if they’re not downright sneering at the songs they claim to describe: Take “bro country” or “PBR&B.”

As A Dockumentary makes clear, “yacht rock” still reliably elicits chuckles. But even if that humor helped these musicians gain younger followers, it often runs contrary to the tone and themes of their songs. “The term emerged from what was essentially a comedy show,” which had “a really big impact on the way that the music is now ironically appreciated,” Petrusich points out. However, “the records that [these artists] were making were entirely sincere.”

Can those records — and the artists behind them — ever be taken seriously if they’re still being laughed at? Loggins is a surprisingly versatile songwriter with a sinuous delivery and a knack for unpredictable funk. McDonald’s voice stood out even during a time when commanding voices were ubiquitous; songs like “You Belong to Me” and “I Keep Forgettin’ (Every Time You’re Near)” are essential contributions to the soul canon. But when these acts are lumped into yacht rock, they are relegated to the minor leagues, stuck as purveyors of slick chill-out music for the aging and affluent.

“I’ve made peace with ‘yacht rock,’ but for the first few years, I just hated it,” Pack says in A Dockumentary. “I’m like, ‘Why did they pick our generation to make all of our music into a big joke?’”

HipHopWired Featured Video

CLOSE

Beyoncé has long since been considered one of the most innovative artists of her generation, as evidenced by the warm reception to her recent country music-influenced album, Act II: Cowboy Carter. This past Monday, Beyoncé accepted The Innovator Award from the legendary Stevie Wonder at the 2024 iHeartRadio Music Awards and delivered a moving speech.

The 2024 iHeartRadio Music Awards took place on Monday (April 1) at the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles, Calif. The star-studded event saw Beyoncé up for R&B song of the year for “Cuff It along with a R&B artist of the year nod.

Stevie Wonder took to the stage to announce the Houston superstar as the recipient of The Innovator Award and was met with measurable applause. Yielding the stage to Queen Bey, Wonder was showered with praise from the singer and entertainer who casually dropped that Wonder played the harmonica on her “Jolene” remake from Cowboy Carter.

Beyoncé came to the stage decked out in a Black and gold leather outfit no doubt inspired by the recent themes from her latest album, complete with a hat that was also emblazoned with gold. After thanking Wonder for his contributions to music and her album, Beyoncé spoke with confidence and eloquence.

“Tonight, you called me an innovator and for that, I’m very grateful,” Beyoncé said. “Innovation starts with a dream. But then you have to execute that dream and that role can be very bumpy. Being an innovator is saying what everyone believes is impossible. Being an innovator often means being criticized, which often will test your mental strength. Being an innovator is leaning on faith, trusting that God will catch you and guide you.”

Also winning that night was SZA, who took home the R&B Artist and R&B Song award for “Snooze” from the singer’s SOS album, which also took home an award.

The full acceptance speech can be viewed in the clip below.

[embedded content]

—

Photo: Kevin Mazur / Getty

Like many good things, it started with a deep dive into yacht rock.

Scott Barkham, who manages the experimental soul outfit Hiatus Kaiyote, was trawling Spotify’s less-traveled byways looking for hidden yacht rock gems when he happened across “Dreaming,” a snappy-yet-plush track by the 23-year-old singer-songwriter-producer Gareth Donkin. “It was really well constructed and executed,” Barkham recalls. “So I investigated further.” On Instagram, he found a video of Donkin covering Bobby Caldwell’s wistful 1980 classic “Open Your Eyes.” “That really got my attention,” Barkham says. He now co-manages Donkin.

Donkin’s debut album Welcome Home, which is out Friday (Aug. 24) on the young label drink sum wtr, is grounded in immaculate R&B from the late 1970s and early 1980s — delicate falsetto, giddily elaborate vocal harmonies, opulent keyboards, nimble bass lines. There are echoes of Debarge, Kenny Loggins, Quincy Jones‘ productions for George Benson and James Ingram, and a host of fragile soul ballads that seem on the verge of evaporating like smoke before a stiff breeze.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

“I really love that classic sound, and I feel like that’s a hole in today’s scene,” Donkin says. “Some people like Silk Sonic and Tom Misch are killing it by revisiting that.” His goal: “Bringing the character from that era’s music” into the present.

Growing up in France near the Swiss border, Donkin started playing piano at age eight and became addicted to the production software program Ableton at 13, the year before he moved to London. “I’ve had such a fascination with music and the creation of it since, well, forever,” he says. “Around the house we were always listening to Prince, Stevie Wonder, Jamiroquai, all the greats.”

[embedded content]

While Donkin spent some time playing drums, he mostly works with keyboards and technology to translate his ideas. “I can hear parts and find MIDI instruments or very realistic sounding samples to realize and execute those,” he explains matter-of-factly. “A lot of the songs I’ve made I’ve kind of written up here” — he points to his forehead — “before even coming to the piano and playing it out.”

His music found a wider audience in 2019 with “Catharsis,” which contrasts airy, mercurial vocals and a needlepoint guitar solo with an unwavering neo-soul beat. “That was the first fully fleshed-out song that I wrote and recorded vocals over,” Donkin says. It “caught the eyes and ears of the wider producer/songwriter community on Soundcloud and Spotify. This led to a lot of collaboration opportunities, and music platforms such as Soulection to discover my music and [in turn] put a lot of people onto it.”

Much of the music on Welcome Home was started the following year, during the tumult of the pandemic. Isolation, despite its many drawbacks, did not hamper Donkin’s ability to conjure a sumptuous sound — “Nothing We Can’t Get Through” and “Tell Me Something” come on like they’re auditioning for inclusion on the back half of Michael Jackson‘s Off the Wall. (The reference point he cited for the string arrangement on the former was Disney scores.)

For more oomph, there’s “‘Til the End of Time (Night Sky),” a harmony showcase underpinned by a tricky, propulsive beat that stutter-steps like Al Green’s “I’m Glad You’re Mine,” and “Something Different,” a bright, crunchy, just-too-slow-to-disco track with a virtuosic, head-nodding outro. (That outro is “the oldest part of the record;” Donkin wrote the chords at age 18 while sitting in an airport in Greece.)

[embedded content]

After Barkham heard “Dreaming” — and found that he had already saved “Catharsis” to his library on a previous Spotify discovery expedition — he reached out to Donkin. “When I really love the artistry, I’ll offer my help,” Barkham says. Soon he was listening to an earlier version of Welcome Home. Donkin “was referencing Ashford & Simpson, obscure yacht rock like Bill LaBounty, Brazilian music,” Barkham marvels. “The level of sophistication in his music and his production went way beyond what I was expecting.”

Barkham asked Donkin’s permission to share the music with a few people whose taste he admired. That group included Nigil Mack, a former major-label A&R who helped sign Kid Cudi. Mack was impressed: “To be so young but be able to write at that top-line level kind of blew me away,” he says. “So did his vocal tone.” Mack founded drink sum wtr, which shares services with the indie stalwart Secretly, last year. Donkin was among his first signings.

[embedded content]

With one album done, he is already thinking about his next release. “I’ve been on a listening binge with Earth, Wind & Fire, and their arrangements and the horns parts are just incredible,” Donkin says. “With the next project I can hopefully get bigger horn parts.”

He’s also in the process of honing a mostly untested live show. Donkin “needs to do tons of shows and start to just play in London regularly and just get himself out there as often as possible,” Barkham says. “I performed some of the songs when they were still in demo stages but not as much as I would like to,” Donkin acknowledges. “I hope to hit the road next year.”

But first, Welcome Home: “I’ve always envisioned my first big statement being something that I work on over time that just shows where my head has been musically speaking,” Donkin says. “I’m ready to let people in.”

-

Pages

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio