nashville

Page: 2

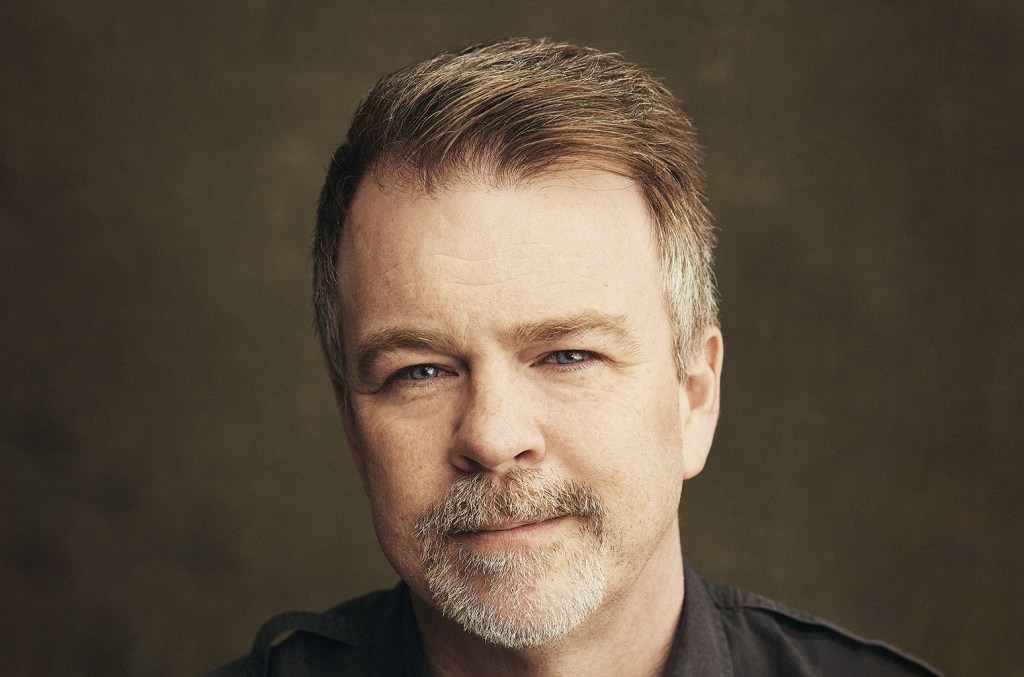

Sony Music Nashville has restructured its radio promotion team, appointing Dennis Reese as senior vp, radio marketing & promotion. Reese will oversee the development and execution of the strategic radio promotional plans for both the RCA Nashville and Columbia Nashville imprints.

Reese will report to Sony Music Nashville chair/CEO Taylor Lindsey and president/COO Ken Robold, and will start in his new role on Feb. 14.

Reese spent the past year at Neon Coast, supporting the artist roster including Kane Brown, Restless Road, Nightly, Dylan Schneider and Kat Luna. His new role marks a returning of Reese to SMN; Reese previously spent seven years leading the RCA Nashville imprint. He joined RCA Nashville after working in pop music at Epic Records, Capitol Music Group, Elektra Records and Columbia Records.

Trending on Billboard

“We are thrilled to welcome back Dennis to the company,” Lindsey said in a statement. “His experience at both the country and pop formats, excellent leadership skills and dedication to the artists he’s worked is unmatched and we are fortunate enough to have him this time at the helm of our promotion team. SMN remains committed to promoting our artists at radio and we know Dennis will continue to bring the No. 1s and advocate for our artists every day.”

Reese’s appointment follows a recent organizational restructuring at Sony Music Nashville, with several radio promotion team staffers having exited as part of the restructuring. Among those that exited were SMN senior vp, promotion Lauren “LT” Thomas, Columbia Nashville senior director, promotion Lauren Bartlett, Columbia Nashville directors of promotion Paige Elliott and Lisa Owen, as well as Sony Music Nashville manager of promotion and artist development Paul Grosser.

Regarding the exits, Sony Music Nashville said in a statement obtained by Billboard, “Our focus is always on being the best partners for our artists and the creative community, especially in this rapidly evolving marketplace. Today we made changes to our team structure to streamline our resources and be more successfully connected to our valuable radio partners across RCA Nashville and Columbia Nashville.”

In November, Lindsey was named as chair/CEO, with Robold promoted to president/COO, as Randy Goodman announced his retirement after running the label since 2015.

Sony Music Nashville’s artist roster includes Brown, Luke Combs, Megan Moroney, Old Dominion, Nate Smith and more.

Dwight Yoakam and Turnpike Troubadours and a string of other artists are set to help raise funds to aid those impacted by the greater Los Angeles-area wildfires, with a concert at Nashville‘s Bridgestone Arena.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

On Feb. 19, Yoakam and Turnpike Troubadours will lead LA Revival, a special benefit concert presented by Thirty Tigers and Triple Tigers. The show will also feature performances from “Burning House” hitmaker Cam, Corey Kent, Carter Faith, Shane Profitt and Brit Taylor.

All of the proceeds from the event will go to the MusiCares LA Fire Relief Effort, to help those affected by the wildfires in the greater Los Angeles area last month. MusiCares was founded by The Recording Academy in 1989; the organization offers preventative, emergency and recovery programs, offering a safety net to aid the health and welfare of those in the music community.

Trending on Billboard

LA Revival is just one of many recent concerts that have raised funds to help those who have been impacted by the wildfires. The recent FireAid concert, which featured artists including Green Day, Billie Eilish, Jelly Roll, Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, has raised more than $100 million to date. Meanwhile, The Recording Academy raised nearly $9 million on Sunday (Feb. 2), when the Grammy Awards aired; throughout Grammy weekend, the Recording Academy and MusiCares raised over $24 million for charitable activities.

In November, Yoakam released his first album in nearly a decade, Brighter Days. The long-tail influence of California’s country music scene has been embedded in Yoakam’s music since the beginning; In the 1980s, he pursued a career in Nashville, but soon decamped to California, soaking in the influence of Buck Owens and the Bakersfield sound, and his unique sound resulted in his debut project Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc.

This year, Turnpike Troubadours will also join Willie Nelson’s Outlaw Music Festival Tour on select dates. They also recently announced two dates at the iconic outdoor venue Red Rocks, on May 8-9.

Tickets for LA Revival will go on sale Feb. 5 starting at 5 p.m. CT.

Ben Vaughn, president/CEO of Warner Chappell Nashville, died on Thursday (Jan. 30). A cause of death was not disclosed. He was 49.

The much-beloved Vaughn, who was Billboard‘s Country Power Players executive of the year in 2020, joined Warner Chappell Nashville (WCN) in 2012 and was promoted to president in 2017, adding the role of CEO in 2019. The Belmont University alumnus was honored with Belmont’s Music City Milestone Award in 2015.

Warner Chappell Music co-chairs Guy Moot and Carianne Marshall released the following memo to Warner Chappell Music staffers that read in part, “It is with broken hearts that we share the unthinkable news that Ben Vaughn, President & CEO of Warner Chappell Nashville, passed away this morning. Our deepest condolences are with his family and many friends.”

Under Vaughn, WCN had consistently dominated the country music publishing market. In 2024, they were crowned ASCAP Country Music and BMI Publisher of the Year (for the fifth time) and marked their third consecutive quarter at No. 1 on Billboard’s Country Airplay publisher rankings. Apart from Q3 of 2022 to Q3 of 2023, Warner Chappell Nashville had held the quarterly top spot, dating back to the first quarter of 2017. In November 2019, ASCAP, BMI and SESAC all named WCN their country publisher of the year — only the third time a publishing company has been honored as such, and a first for WCN.

Trending on Billboard

Among the singer/songwriters Vaughn worked with were Thomas Rhett, Zach Bryan, Chris Stapleton, Riley Green, Warren Zeiders, Hunter Phelps, Bailey Zimmerman, Jessi Alexander, Liz Rose, Josh Phillips, Thomas Rhett, Nicolle Galyon and Randy Montana.

The father of three was extraordinarily passionate about songwriters, especially developing ones, and relished helping young singer/songwriters find their voice and their first record deal. “There’s so many people that want that record deal, so helping someone get to that spot is one of the hardest things in the music business,” Vaughn told Billboard in 2020. “So the job is to take away the nos and help that person get to a place where you get a yes.”

Tributes poured in quickly. Jon Platt, chairman/CEO of Sony Music Publishing, who worked with Vaughn at EMI and then brought him over to Warner Chappell in 2012, said in a statement, “I am deeply saddened by the passing of my friend Ben Vaughn, and united in grief with the entire songwriting community. Ben dedicated his life to songwriters. As an exceptional leader and mentor, he leaves an indelible mark on the music business. I extend my deepest condolences to his loved ones and all who were touched by his spirit. I feel privileged to have known Ben and shared a close relationship with him. He was the best of the best and I will miss him greatly.”

“Ben was warm, welcoming, and always someone that supported and elevated the American songwriter,” says Lucas Keller, president/founder of Milk & Honey. “The world will not be the same without him – this is a loss most cannot process today. We met 15 years ago on my first trip to Nashville when he was at EMI, and I’ll never forget him.”

“Our hearts are heavy today in learning about the passing of longtime ACM Board Member and former ACM Board Chair, and good friend to all of us, Ben Vaughn,” added Damon Whiteside, CEO of the Academy of Country Music. “Ben was a champion of the country music genre and strong advocate for songwriters and good songs. He served as board chair of the Academy in 2018 and was the first music publisher to serve as chairman in the Academy’s history, in addition to serving on the ACM Lifting Lives board. On behalf of the ACM Board, ACM Lifting Lives Board, and the ACM staff, we send our condolences to Ben’s family, friends, coworkers, and all of those who crossed his path and were lifted up by his passion. His memory will live on forever through the great music he made happen.”

Vaughn grew up in the tiny community of Sullivan, Ky., and comes from “a proud tradition of coal miners, teachers and mechanics,” he told Billboard. As a high school student, he got a job as a weekend DJ at country radio station WMSK-FM, which set him on a path to Nashville. “I would devour the vinyl and read all the publishing and writer credits,” he told Billboard. “I thought, ‘I want to go where these people are.’ ”

That led him to Nashville’s Belmont University and an internship at WCN in 1994 under then-executive vp Tim Wipperman, who taught Vaughn the intricacies of publishing. While there, he got to know producer Scott Hendricks, whose Big Tractor publishing company had a partnership with WCN. Hendricks was so impressed with Vaughn that he eventually asked him to run Big Tractor — while Vaughn was still a college student. “He said, ‘I’m going to give you six months to see how it goes, but if you quit school, I’ll fire you,’ ” recalls Vaughn.

Through the decades, Vaughn remained in wonderment of songwriters and the new worlds they created. “It is awe-inspiring how much talent it takes to create something out of nothing that literally can make the whole world sing,” he said. “The most sacred responsibility is to help connect writers’ dreams to their goals. The fact that as publishers we are trusted to hold that space for them is everything.”

Moot and Marshall’s full memo to WMG:

To everyone at WMG,

It is with broken hearts that we share the unthinkable news that Ben Vaughn, President & CEO of Warner Chappell Nashville, passed away this morning. Our deepest condolences are with his family and many friends.

Ben has led our Nashville team since 2012, and we know that many of you around the world got to know him over the years. Anyone who had the pleasure of working with him will be as shocked and saddened as we are.

First and foremost, Ben was an extraordinary human being. He met everyone with enthusiasm, warmth, and generosity. His smile was huge, and his sense of humor was infectious.

He was always a passionate advocate of songwriters and a topflight music publisher. The Nashville community has lost one of its greatest champions, and he will be profoundly missed by so many across our company and the entire industry.

We are planning to visit the Nashville team very soon and thank you all for helping support them through this awful tragedy.

With love,

Guy & Carianne

This is a developing story.

Several roots-based music luminaries will perform to help aid various communities, as part of the third annual Hello From the Hills concert, slated Sunday, Jan. 26 at Nashville’s City Winery.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Ruby Amanfu, Cory Branan, Hayes Carll, Brad Goodall, Silas House, Amanda Shires, Charlie Starr of Blackberry Smoke, and Jesse Welles are all set to take the stage at the intimate Music City venue, with author and storyteller House — most recently known for his work on Tyler Childers’ music video “In Your Love” — hosting the event.

The annual Hello From the Hills concert was founded by Hope in the Hills and The Hello in There Foundation, with the past two concerts drawing performers including Jason Isbell, Tyler Childers, Shires, Sierra Ferrell, Wynonna Judd, Gabe Lee, and Amythyst Kiah. Event proceeds have made it possible for the event’s organizers to make over $100,000 in community grants over the past two years, benefiting organizations including Raphah House, Healing Institute, MusiCares and Musicians Recovery Network.

Trending on Billboard

Jody Whelan, Oh Boy Records managing partner and Hello in There Foundation board member and treasurer, tells Billboard, “I feel like at this event, it’s so much more than just a performance. You really see the heart of these performers. They are more than just artists, more than just songwriters. You get to see the love they have and the passion they have for different organizations and they see how it affects communities.”

Hope in the Hills’ Ian Thornton tells Billboard, “Music is the thing that brings people together — that’s the business Jody and I are both in. We just know so many great artists and folks have been gracious about donating their time. Nobody gets paid for this. I think the mission in and of itself pushes them to want to be part of it.”

This year, proceeds from the concert will benefit the veterans assistance programs Operation Stand Down Tennessee and Building Lives, as well as My Fathers House Nashville, which provides shelter, life skills and education to fathers who have faced homelessness, incarceration and other adversities. As well, merchandise sales will aid those impacted by the ongoing wildfires in the greater Los Angeles area.

Hello From the Hills

Courtesy Photo

Whelan says, “It’s great to be able to reach into some of these smaller community-based organizations and support them. I love the big organizations that we support, but $10,000 can go really far to a small, local organization — and that equals, ‘We can help this many people.’ We try to invite people from the organizations that are benefiting to be there, so they can see it and talk about their work.”

The Hello in There Foundation was established in 2021 by the family of the late singer-songwriter John Prine and is guided by message of Prine’s 1971 song “Hello in There.” In 2017, Hope in the Hills was launched by members of Tyler Childers’ team, as well as community members in Kentucky, with the aim of combatting the opioid crisis and supporting recovery throughout Appalachia.

“I’ve long admired the work that Ian and the folks at Hope in the Hills and Healing Appalachia have done,” Whelan says. “The Prine Family started our foundation a few years ago and we’ve been close to them for a long time. So we thought, ‘Can we do something to work together?’ The way we formatted it was we each picked one charity that we felt served our mission and then came together and support another organization.”

Whelan adds, “A lot of times, we let John’s songs kind of guide us. This year, it is focusing on veterans and those struggling with addiction, and John’s song ‘Sam Stone’ is a huge touch point. We think about the organizations and how it might tie in with the work that Hope in the Hills is doing. Once you start talking with these organizations, fighting addiction is such a big part of so many different organizations, even if it’s not their primary thing, like homelessness and addiction impacting veterans. Addiction is such a big topic and it affects lives in so many different ways.”

Looking ahead, Thornton is positive about the continued acceleration of the event’s impact: “I’d like to keep this as an annual event coming to Nashville. We’ve talked about bringing it to other cities, too, because I love the idea of being able to help local community organizations in other cities, especially in this region. I don’t know when we’ll have time to do that, but it will happen soon. I don’t see us going into the virtual space anytime soon. We want to keep getting people in rooms, together in community, and sharing their stories.”

Tickets are still available for this year’s Hello From the Hills at citywinery.com.

HipHopWired Featured Video

Source: Terry Wyatt / Getty

The Nashville high school shooter was a Black teen revealed to have embraced neo-Nazi ideals such as being a “Groyper incel,” according to his social media.

The male student who shot two fellow students, killing one at a high school in Nashville, Tennessee, on Wednesday morning (January 22) was revealed to be an African-American student who left a manifesto posted to social media showing his embrace of white nationalism and self-hate. He was identified as Solomon Henderson, a 17-year-old in the Reserve Officers Training Corp at Antioch High School. Henderson would take his own life after the shooting.

The 300-page manifesto was posted to Henderson’s account on X, formerly Twitter, four hours before he walked into the cafeteria at the school at 11 A.M. Central time and fired multiple rounds with a pistol, killing 16-year-old Josselin Corea Escalante and grazing one 17-year-old unidentified male student. The document showed that Henderson’s motivation for the shooting was a hatred of Black people. “I’m ashamed to be black. I feel like s*** being a n******”, he wrote in the text.

Another message in the document posted before the incident read, “God I am ugly. 4 hours to go,” which was imposed over a photo of Henderson. The document also revealed that Henderson considered himself a “Groyper Incel,” a term used by followers of the neo-Nazi figure Nick Fuentes and members of the involuntarily celibate movement. Henderson cited Fuentes as a major influence, in addition to far-right figure Candace Owens and Kanye West aka Ye, along with other white nationalist mass murderers in inspiring his violence.

Henderson’s manifesto was also filled with notes on his plans for the shooting, stating that he initially planned to commit the act on Thursday but moved it up because he was scared of “failing to kill myself or go to jail” and that he aimed to “kill at least 10 people.” He also detailed his embrace of Neo-Nazi ideals, writing: “We must aid the Aryans regardless of our race.”

Henderson also was confirmed by police to have live-streamed the shooting on multiple platforms, including Kick which shut down his account shortly after the incident. “We extend our thoughts to everyone impacted by this event,” the company said in a statement on X, formerly Twitter. “Violence has no place on Kick. We are actively working with law enforcement and taking all appropriate steps to support their investigation.”

Former Beatles drummer Ringo Starr has long threaded country music into his work, both as part of the Fab Four, and his decades of solo work.

During his tenure with the Beatles, Starr sang lead on the Fab Four’s cover of the Buck Owens classic “Act Naturally.” Later, as a solo artist, Starr decamped to Nashville to record his 1970 country album Beaucoups of Blues, crafted with Nashville session musician Pete Drake.

Now, more than five decades after that project, the 84-year-old Starr continues his country inclinations, crafting his recently-released new country album Look Up with legendary producer/musician T Bone Burnett, the former Bob Dylan band member known for his production work on the O Brother, Where Art Thou? and Walk the Line soundtracks, as well as his work with a range of artists, including Robert Plant, Elton John and Brandi Carlile.

Starr celebrated the release of Look Up with two concerts at Nashville’s famed Ryman Auditorium, on Tuesday (Jan. 14) and Wednesday (Jan. 15). Each show featured Starr welcoming a star-studded lineup of his fellow music luminaries, including Sheryl Crow, Jack White, Emmylou Harris, Rodney Crowell, The War and Treaty, Jamey Johnson, Billy Strings, Molly Tuttle, Mickey Guyton, Sarah Jarosz and Larkin Poe. Burnett hosted the show, welcoming artists throughout the evening, as some performances featured artists in collaboration with Starr, while other performances featured the evening’s guest offering solo performances.

Together, they spearheaded a night of music that highlighted Starr’s long-forged country connections and the wealth of musical talent Nashville encompasses beyond the country commercial mainstream, incorporating songs from Starr’s Look Up, but also several country-tinged Beatles songs along the way.

“I feel blessed tonight, with all these great players coming out,” Starr told the audience.

Noting the work of artists including Strings, Tuttle and Jarosz, Burnett commented at one point, “Some of the most exciting stuff in music is happening in bluegrass.”

Backing the artists was an ace band of revered musicians that included Mike Rojas, Daniel Tashian, David Mansfield, Dennis Crouch, Paul Franklin and Jim Keltner. White joined Starr to open the show with a rendition of “Matchbox,” and later returned to the stage to perform an intricate, blazing version of “Don’t Pass Me By.”

Tuttle called taking part in Starr’s Look Up album “the honor of a lifetime, working with Ringo and T Bone.” The Grammy winner then played what she called “the first Beatles song I ever heard,” offering a rendition of “Octopus’s Garden,” from The Beatles’ Abbey Road album. Elsewhere in the evening, Crowell and Jarosz performed rollicking version of “Act Naturally.”

Elsewhere, Strings offered a blistering performance of “Honey Don’t,” Guyton gave a powerful, elegant vocal showcase on “You Don’t Know Me at All,” Johnson dipped into grizzled blues-rock territory on “Have You Seen My Baby,” and Larkin Poe teamed with Starr for “Thankful” and also offered a sultry version of “I Wanna Be Your Man.”

Throughout the evening, the artists feted Starr for not only his musical acumen and lasting musical influence, but also for his signature devotion to crafting music that uplifts.

“I needed this,” Crow said at one point, adding, “I can’t think of anybody who emanates love and peace like Ringo — and it’s not a brand, he really does…he believes in it.”

Starr’s two Ryman Auditorium shows were taped for the upcoming television special Ringo & Friends at the Ryman, which will air on CBS and stream on Paramount+ this spring.

The show concluded, appropriately, with an all-star singalong of The Beatles’ classics “Yellow Submarine” and “With a Little Help From My Friends,” which saw additional artists join Starr onstage, including rock and country music trailblazer Brenda Lee (the Beatles once opened for Lee back in the 1960s, prior to the Fab Four’s breakthrough).

Here, Billboard highlights five top moments from Ringo Starr’s Wednesday evening show.

Jack White Brings Electrifying Performances to Ryman Stage

Artist manager Justin McIntosh has launched JTMC Entertainment, welcoming actress, singer and New York Times bestselling author Kristin Chenoweth to the roster. McIntosh will continue to work with singer, entertainer, author, actress and businesswoman Reba McEntire, whom he has represented since 2023. “2025 marks my 20-year anniversary of working in this business, and I am […]

Dualtone Music Group president and partner Paul Roper died on Tuesday (Dec. 17) following a battle with cancer. Roper was 45. A statement from Nashville-based Dualtone Music Group noted, “Paul’s vision and unwavering commitment continues to define the heart and soul of Dualtone. He led Dualtone and his team with dedication, authenticity, humor, and kindness […]

Morgan Wallen‘s Nashville bar, restaurant and music venue will soon have its neon sign, joining the slate of massive signs beckoning both tourists and locals to downtown Music City. Explore Explore See latest videos, charts and news See latest videos, charts and news On Dec. 17, the Metro Nashville City Council gave permission for the […]

Pam Matthews will retire from her role as executive director at the International Entertainment Buyer’s Association (IEBA) in the first quarter of next year after 11 years at the helm of the talent buying and booking organization. Matthews modernized the group’s annual conference in Nashville, transforming the once sleepy get-together into a must-attend annual conference […]

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio