Music

Page: 90

Trending on Billboard

Usher took the stage at the 2025 Billboard Live Music Summit Monday afternoon (Nov. 3) to reflect on all of the stages he’s taken over during his 28-year touring career.

The R&B superstar and Gail Mitchell, Billboard executive director of R&B and hip-hop, walked out to his 2001 Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 “U Got It Bad” at the 1 Hotel in West Hollywood, Calif., which Mitchell reminded he previously said in his 2024 Billboard cover story that it was his favorite song to perform live. “I think because of the connection between me and the audience,” he said at the time. Today, he added: “I want to impress them. I would like to be as theatrical and use my imagination as much as I possibly can to lift the song higher than what it was when I delivered it as a piece of intellectual property.”

Following his two Las Vegas residencies from 2021 to 2023 and his Super Bowl LVIII halftime show performance (also in Vegas) last year, Usher embarked on his most recent Past Present and Future Tour. The 83-date international jaunt became his highest-grossing and best-selling tour yet, according to Billboard Boxscore, by grossing $183.9 million and selling 1.1 million tickets over 80 shows. He has a reported career gross if $422.6 million from 3.3 million tickets over 334 shows.

But before becoming a marquee act, Usher served as an opener for Diddy‘s 1997 No Way Out Tour, Mary J. Blige‘s 1997-98 Share My World Tour and Janet Jackson‘s 1998-99 The Velvet Rope Tour. “I had another notch on my belt in terms of what I was capable of being able to handle, so that when I went to try to headline my own tours, we knew that we had the ability to hold a crowd,” he explained.

He told industry audience members a story about his time opening for Diddy: As his 1997 hit “You Make Me Wanna…” was steadily climbing the Hot 100 (where it eventually peaked at No. 2), the crowd coming to see Usher gradually grew from 10 people to a packed house. Diddy told Usher he wanted him to come out during his headlining set, but Usher recalled saying, “Nah, I’m cool. I’m gonna stay right where I’m at because I wanna earn my keep. I’m here for a reason. I want to someday be where you are.”

By the time Usher embarked on his debut headlining tour, the 8701 Evolution Tour in 2002, he remembered “the importance of paying tribute” during those shows. “I’m an artist who was inspired by the legends. If I study the legends, then hopefully one day, I will be one,” he said, adding that he performed covers of Bobby Brown, Babyface and Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis because he didn’t have enough of his own hit records at the time and wanted to still captivate his audiences.

The Coming Home artist also teased “something coming. I’m in the midst of working on something that may shine a light on a very specific period of my life and around performance. Just stay tuned. There is true value in live,” he said. He later argued that there’s also true value in R&B. “I want people to continue to celebrate the music and legacy that is the foundation that I am. It comes from soul music, it comes from the South. It comes from a very wide collective of being exposed to many different artists from many different genres, but most importantly, R&B.

“In the same way that I think all other industries have managed to monetize what they are — whether it’s hip-hop, rock & roll, country — I want the same thing for R&B,” he continued. “That is the thing that I haven’t done yet. I want us to celebrate the legacy of what it is that we created, not just look at these nostalgic things that have come and gone, but be able to savor them and savor their legacy.”

Mitchell later presented Usher the Legend of Live Award following the panel. He isn’t the only superstar panelist during the Live Music Summit. Billboard cover star Rauw Alejandro and Hans Schafer, senior vp of global touring at Live Nation, will sit down with Billboard Español/Latin chief content officer Leila Cobo later this afternoon to discuss the reggaeton artist’s emergence as one of the live sector’s most sought-after stars.

Trending on Billboard

HUNTR/X remains triumphant as “Golden,” from Netflix’s record-breaking animated movie KPop Demon Hunters, leads the Billboard Global 200 and Billboard Global Excl. U.S. charts for a 14th week each. In July, the song became the first No. 1 on each survey for the act, whose music is voiced by EJAE, Audrey Nuna and REI AMI.

Plus, LE SSERAFIM and j-hope, of BTS, serve up a top 10 debut on both charts with “Spaghetti.”

The Billboard Global 200 and Global Excl. U.S. charts rank songs based on streaming and sales activity culled from more than 200 territories around the world, as compiled by Luminate. The Global 200 is inclusive of worldwide data and the Global Excl. U.S. chart comprises data from territories excluding the United States.

Chart ranks are based on a weighted formula incorporating official-only streams on both subscription and ad-supported tiers of audio and video music services, as well as download sales, the latter of which reflect purchases from full-service digital music retailers from around the world, with sales from direct-to-consumer (D2C) sites excluded from the charts’ calculations.

“Golden” leads the Global 200 with 120.8 million streams (down 2% week-over-week) and 13,000 sold (down 8%) worldwide in the week ending Oct. 30.

The entire Global 200’s top five holds in place: Taylor Swift’s “The Fate of Ophelia” at No. 2, after two weeks at No. 1 in October; her “Opalite” at No. 3, after hitting No. 2; Alex Warren’s “Ordinary” at No. 4, following 10 weeks on top beginning in May; and Olivia Dean’s “Man I Need” at No. 5, after reaching No. 4.

LE SSERAFIM and j-hope’s “Spaghetti” makes a piping hot start at No. 6 on the Global 200 with 48.4 million streams and 14,000 sold worldwide following its Oct. 24 release. LE SSERAFIM earns its first top 10 on the chart, while j-hope adds his second as a soloist; here’s an updated count of BTS members’ top 10 totals on the chart as soloists: Jung Kook (five); Jimin, JIN (three each); j-hope, V (two each); and Suga (one). BTS boasts 11 top 10s as a group.

“Golden” commands Global Excl. U.S. with 93.3 million streams (down 2%) and 7,000 sold (down 10%) beyond the U.S.

“The Fate of Ophelia” holds at No. 2 on Global Excl. U.S. after two weeks at the summit in October.

“Spaghetti” debuts at No. 3 on Global Excl. U.S. with 42.7 million streams and 9,000 sold. LE SSERAFIM previously hit the top 10 with “Easy” (No. 6 peak) and “Perfect Night” (No. 8), both in 2024. “Spaghetti” is also j-hope’s third top 10 on the chart solo; here’s an updated rundown of BTS members’ top 10 totals on the survey as soloists: Jung Kook (seven); Jimin (five); JIN, V (four each); j-hope (three); and Suga (one). BTS has notched 11 top 10s as a group.

“Ordinary” ascends 5-4 on Global Excl. U.S., after eight weeks at No. 1 starting in May, and “Opalite” drops to No. 5 from its No. 3 high.

The Billboard Global 200 and Billboard Global Excl. U.S. charts (dated Nov. 8, 2025) will update on Billboard.com tomorrow, Nov. 4. For both charts, the top 100 titles are available to all readers on Billboard.com, while the complete 200-title rankings are visible on Billboard Pro, Billboard’s subscription-based service. For all chart news, you can follow @billboard and @billboardcharts on both X, formerly known as Twitter, and Instagram.

Luminate, the independent data provider to the Billboard charts, completes a thorough review of all data submissions used in compiling the weekly chart rankings. Luminate reviews and authenticates data. In partnership with Billboard, data deemed suspicious or unverifiable is removed, using established criteria, before final chart calculations are made and published.

Trending on Billboard Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo have a thrillifying night in the works for Wicked fans, with the pair gearing up to star in NBC’s upcoming One Wonderful Night concert special — the first sneak peek of which dropped Monday (Nov. 3). In the 40-second clip, lovers of the Broadway musical’s soundtrack are […]

Trending on Billboard Carly Rae Jepsen is cutting right to the feeling with her announcement that she’s pregnant with her first child with husband Cole Marsden Greif-Neill. The “Call Me Maybe” singer hopped on Instagram on Monday (Nov. 3) to confirm that she and her newlywed husband are going to be parents. “Oh hi baby,” […]

Trending on Billboard 2025 will be a year marked by a moment that went viral on the internet: that of a musician who swept the streets in the early mornings in Mexico City and who, with a video on TikTok, managed to connect with millions through an uplifting song, “Sueña Lindo,” and his personal story. […]

Trending on Billboard We’re currently focused on next year’s Super Bowl halftime show headliner, but the 2024 master of ceremonies is still at the center of the culture. After the Los Angeles Dodgers defeated the Toronto Blue Jays at the 2025 World Series on Saturday (Nov. 1), the City of Angeles reached for the only […]

Trending on Billboard

This week, Kaitlin Butts celebrates inking a label deal with Republic by issuing a tender revamping of a Jimmy Eat World hit. Meanwhile, Riley Green teams with Jamey Johnson for a robust new collab, and ERNEST, Sammy Arriaga and newcomer Joshua Slone also offer new tracks.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

Check out all of these and more in Billboard‘s roundup of some of the best country, bluegrass and/or Americana songs of the week below.

Kaitlin Butts, “The Middle”

Butts, who recently inked a deal with Republic Records, offers up a revamped version of Jimmy Eat World’s 2001 hit, transforming it into a soothing, hopeful, acoustic-driven track driven by guitars, fiddle and understated percussion. Butts’ version comes across as tender, wise and thoughtful, particularly on lines such as “Just do your best, do everything you can/ And don’t you worry what their bitter hearts are gonna say.” That’s a timeless message people of all ages can cling to.

Jamey Johnson and Riley Green, “Smoke”

Jamey Johnson welcomes Riley Green for this barn burner, intertwining Johnson’s weathered, gravelly vocal with Green’s burnished twang as they explore the motif of “smoke” with varying meanings throughout the heartbreak-driven track. At various points throughout “Smoke,” the titular phrase references the plumes billowing from an ex’s tires as she speeds away, or the wisps of smoke curling from the end of the lit cigarette he’s using to obscure his pain. Green and Johnson wrote the song with Erik Dylan and recorded the track at the Cash Cabin and Big Gassed Studios, with production from Kyle Lehning and Jim “Moose” Brown, which captures complementary ties between Johnson and Green’s distinct styles.

ERNEST, “Blessed”

In his latest, ERNEST weaves a tale of love and legacy, as this song looks at a piece of land being handed down generation after generation. “Granddaddy bought this slice back in 1962/ It came with a barn, a dog in the yard and a Chevrolet painted blue,” he sings, before sketching his own dreams of passing the land down to his son. Reserved guitars, bass and drums put ERNEST’s vocal at the fore, as he brims with pride about passing down wisdom he hopes his son will continue learning from. “Blessed” precedes ERNEST’s upcoming project Live From The South, out Nov. 21.

Sammy Arriaga, “Before the Next Teardrop Falls”

First-generation Cuban American Sammy Arriaga bridges cultures and languages, combining English and Spanish-language tracks on his bilingual country Latin album Heart in Texas, which released Oct. 31. The album also includes Arriaga’s heartfelt, Spanglish rendition of Latin country trailblazer Freddy Fender’s classic “Before The Next Teardrop Falls” (Fender’s original topped both the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart and Hot 100 in 1975). Arriaga’s version simultaneously pays graceful homage to Fender’s original, while, like the rest of the songs on the album, Arriaga stamps every lyric and message with his unique artistry and warm, welcoming vocal tone.

Joshua Slone, “Your Place at My Place”

Slone makes a striking entrance with his 16-song, debut album Thinking Too Much, which features Slone as the sole writer on each track. The angst-fueled “Your Place at My Place” finds him musing about unfruitful attempts to move past a faded relationship. “No one’s ever taken your place at my place,” the Kentucky native concisely laments. His full project showcases his vivid, vulnerable songwriting, cementing Slone as one of country music’s most compelling new voices.

Taylor Swift’s “The Fate of Ophelia” notches a fourth week at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, encompassing its entire run on the chart so far. Helping the song’s continued Hot 100 command, Swift released its “Alone in My Tower Acoustic Version” for digital purchase Oct. 28, just after 4:30 p.m. ET, ahead of […]

Trending on Billboard Thought you’d seen it all? Not quite. Jeezy just proved that he’s always climbing to new heights after accomplishing something that’s never been done before, earning himself a place in the Guinness World Records. On Saturday (Nov. 1), the trap-music tastemaker made history by performing with 101 orchestra musicians on stage at […]

Trending on Billboard

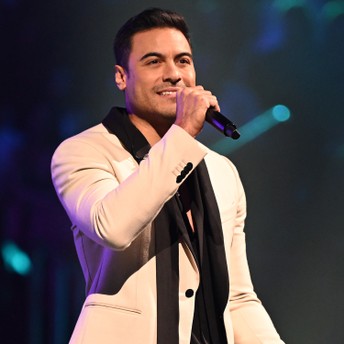

Carlos Rivera chose the Day of the Dead celebration to launch VIDA, a six-song EP filled with nostalgia, delving into mariachi, sierreño and even tumbado music. The Mexican pop star, born in Huamantla, a small town in the state of Tlaxcala, recently presented this material there, proudly showcasing his roots.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

“I want the world to know more about my country’s traditions,” Rivera tells Billboard Español. “We Mexicans celebrate the lives of those who have passed away in a very unique way, with flavors, colors, and music.”

“Mexico is mariachi, Día de Muertos,” adds the singer of “Recuérdame,” a song that was part of the Disney-Pixar animated film Coco (2017), famous for celebrating the way Mexicans deal with the subject of death. “I always thought that if I was going to do a project like this, it had to be looking at life from a different angle. This EP is inspired by loss and grief.”

Released by Sony Music Mexico on Oct. 30, VIDA opens with “Larga Vida,” a song about enjoying every moment with our loved ones. It includes a collaboration with Ana Bárbara accompanied by traditional mariachi, “Cuento de Nunca Acabar,” about trying to forget someone without success. And songs like “Calavera,” a huapango about denying death, and “Alguien,” which talks about being used to replace someone.

The singer says that after his father passed away three years ago, he began composing and searching for songs as a form of catharsis to ease the pain a little and help others who have been through the same situation.

“There are a couple of songs I wrote for my dad when he died,” he says. “One of them is ‘No Es Para Menos,’ in which I talk about the pain coming all at once so that whatever needs to hurt hurts and the suffering ends. In ‘Almas,’ the guitars practically cry from the beginning; the lyrics are about the absence of a person when they leave and places like an armchair are left empty.”

With “Larga Vida,” the focus track, “rather than honoring those who died, I wanted to talk about the importance of enjoying those who are alive and whom we never want to see leave,” Rivera explains. “Originally it was with guitar, which was very beautiful, but I thought we could put more energy into the requinto. So it sounded very sierreño and even tumbado, but using mariachi instruments.”

Regarding the only collaboration on the EP — “Cuento de Nunca Acabar,” with regional Mexican star Ana Bárbara — he says: “From the very beginning, I thought of her to sing it together. Her style of practically crying the songs fit perfectly.”

After participating in the soundtrack for Coco, Rivera had sporadically experimented with regional Mexican music. He did so with mariachi on that occasion and in “100 años” with Maluma. Later, in 2023, he invited Carín León and Edén Muñoz to accompany him on “Alguien Me Espera en Madrid,” and in early 2025, he released “Tu Amor Es Mío” with Fato and Alfredo Olivas.

“I love the genre. It’s my roots, and I want to take it everywhere,” says Rivera. “Fortunately, my music is heard in many places in Latin America and Europe, so I want to take the whole concept of VIDA on my next tour.”

He revealed that he is putting together a band of musicians that will include mariachi, and that he will also perform in palenques. The two-year tour will begin in 2026, during which the artist with two decades of experience will bring his fans hits such as “Que Lo Nuestro Se Quede Nuestro,” “Te Esperaba,” and “Me Muero.” The dates will be announced in the coming weeks.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio