Legal News

Page: 17

Aubrey O’Day has confirmed she will not be taking the stand in Sean “Diddy” Combs‘ federal sex-trafficking trial.

The former Danity Kane member made the announcement on Friday (May 16) during the premiere episode of Amy Robach & T.J. Holmes Present: Aubrey O’Day, Covering the Diddy Trial, an iHeartRadio podcast recorded in New York City.

“I’m not here to testify for the Diddy trial, that I know of,” O’Day said, according to People.

The 41-year-old singer suggested her involvement could still evolve, revealing she had been “contacted by Homeland Security” and had a meeting with the agency, which led March raids on Diddy’s homes in Los Angeles and Miami.

Earlier in the week, O’Day — who appeared on MTV’s Making the Band under Diddy’s mentorship — sparked speculation about a possible court appearance after sharing a cryptic Instagram post from New York City.

“Hey New York!!! Where y’all think I should head first?” she wrote on May 14, including a scale emoji. Us Weekly also reported that a source claimed O’Day was subpoenaed to testify at the trial.

During the podcast episode, O’Day clarified the post’s intent. “I posted on my Instagram that I was here in New York and enjoying myself because I wanted to make it clear to everyone that I am not here testifying,” she said.

Diddy is currently facing multiple federal charges, including sex trafficking and racketeering. His trial is set to resume Monday (May 19). If convicted on all counts, he could face life in prison.

O’Day previously spoke out after Diddy’s September 2024 arrest. “The purpose of Justice is to provide an ending and allow us the space to create a new chapter. Women never get this. I feel validated. Today is a win for women all over the world, not just me. Things are finally changing,” she wrote on X at the time.

Danity Kane, the girl group formed in 2005 on Making the Band, was signed to Diddy’s Bad Boy Records. O’Day was removed from the group in 2008 and later claimed on the Call Her Daddy podcast in 2022 that her exit stemmed from her refusal to comply with non-music-related requests from the music mogul.

Cassie’s husband, Alex Fine, has spoken out in defense of his wife’s harrowing testimony recounting her alleged abuse at the hands of Diddy during the Bad Boy mogul’s trial.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Fine released a statement on Friday (May 16) as Cassie’s four-day stint on the stand came to a close via his wife’s attorney, Doug Wigdor.

“I have felt tremendous pride and overwhelming love for Cass,” he said. “I have felt profound anger that she has been subjected to sitting in front of a person who tried to break her. You did not break her spirit nor her smile.”

Fine continued: “I did not save Cassie, as some have said. To say that is an insult to the years of painful work my wife has done to save herself. Cassie saved Cassie. She alone broke free from abuse, coercion, violence, and threats. She did the work of fighting the demons that only a demon himself could have done to her.”

Alex Fine was present in court for all four days his wife was on the stand this week, as day five of the trial wrapped up on Friday.

“All I have done is love her as she has loved me. Her life is now surrounded by love, laughter and our family,” he added. “This horrific chapter is forever put behind us, and we will not be making additional statements. We appreciate all of the love and support we have received, and we ask that you respect our privacy as we welcome our son into a world that is now safer because of his mom.”

The first week of Diddy’s trial finished on Friday as Cassie was cross-examined by Combs’ attorneys and grilled about various horrifying events and alleged abuse she recalled throughout her four-day testimony.

Looking to put this chapter of her life behind her once and for all, Cassie also released a statement via her attorney about the “challenging” yet “empowering and healing” week she experienced on the stand while digging up painful memories.

“This week has been extremely challenging, but also remarkably empowering and healing for me. I hope that my testimony has given strength and a voice to other survivors, and can help others who have suffered to speak up and also heal from abuse and fear,” she said via Wigdor. “For me, the more I heal, the more I can remember. And the more I can remember, the more I will never forget.”

Cassie continued: “I want to thank my family and my advocates for their unwavering support, and am grateful for all the kindness and encouragement that I have received. I am glad to put this chapter of my life to rest as I turn to focus on the conclusion of my pregnancy, I ask for privacy for me and for my growing family.”

The “Me & U” singer’s testimony ended with Cassie sobbing as she thought about how life would be if she never participated in the alleged days-long “freak-offs” allegedly orchestrated by Diddy.

Cassie and Diddy started dating on and off in 2007 and broke up for good in 2018, bringing the tumultuous relationship to a close. Cassie married Alex Fine in 2019, and the couple is expecting their third child together in the coming weeks.

Diddy is facing charges of sex trafficking and racketeering. Combs’ trial will resume in court on Monday (May 19). If found guilty on all counts, he potentially faces life in prison.

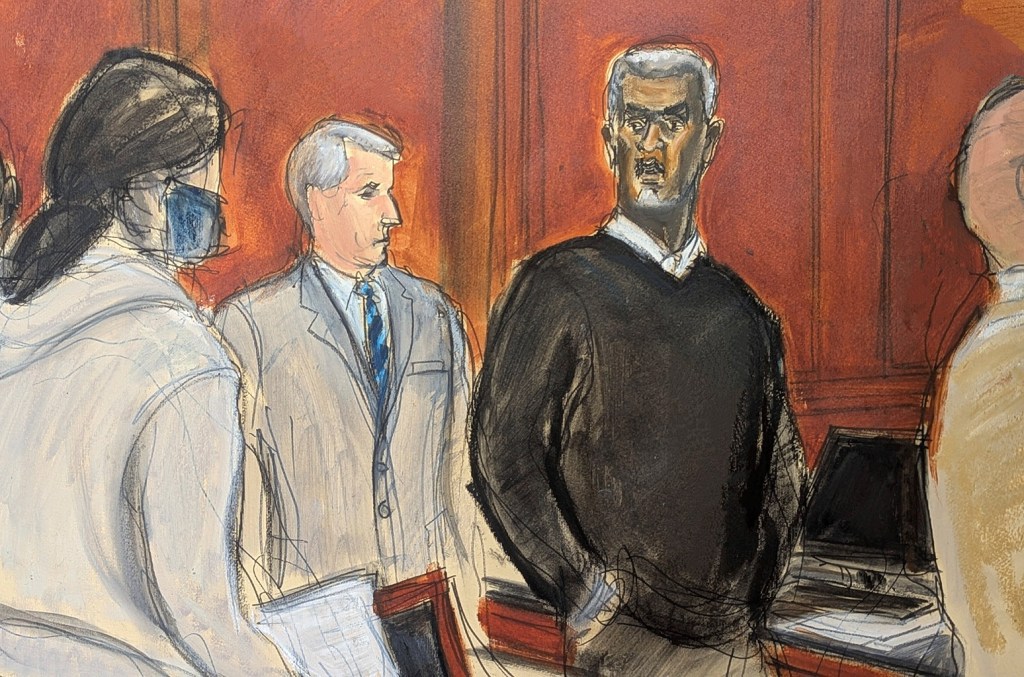

Sean “Diddy” Combs’ ex-girlfriend, Cassie Ventura, faced probing questions about her financial motivations on her last day of testimony in the rapper’s sex-trafficking trial on Friday (May 16), while Danity Kane alum Dawn Richard also took the stand and said she witnessed Combs abusing Ventura.

Richard’s testimony closed out the first week of Combs’ much-awaited criminal trial, in which the music mogul is accused of coercing Ventura and other women into participating in drug-fueled sex shows known as “freak-offs.” R&B singer Ventura, the prosecution’s star witness, spent four days on the stand detailing how Combs allegedly controlled and physically abused her during their 11-year relationship.

Ventura faced her second and final day of cross-examination on Friday from Combs’ attorney Anna Estevao, according to the Associated Press and the New York Times. Defense lawyers had previously suggested they may want to keep questioning Ventura next week, but backed off the request after prosecutors flagged concerns that the very pregnant Ventura might go into labor over the weekend.

Trending on Billboard

Continuing a strategy from the first day of cross-examination, Estevao confronted Ventura with more seemingly loving text messages between her and Combs. Some appeared to support the defense’s theory that the pair’s sex life, while unconventional, was consensual.

“I don’t want to freak off for the last time,” Ventura wrote in one such text to Combs. “I want it to be the first time for the rest of our lives.”

Estevao also tried to imply that Ventura is motivated by money to lie about her experience with Combs, getting the witness to reveal for the first time that she’s getting a $10 million settlement from the Intercontinental Hotel in Los Angeles, where Combs was seen beating Ventura in infamous video footage from 2016.

The newly-revealed $10 million settlement is on top of a $20 million civil payout Ventura got from Combs himself after she sued the rapper in 2023. Estevao noted Friday that Ventura canceled an upcoming concert tour soon after inking that settlement.

“As soon as you saw that you were going to get the $20 million, you canceled the tour because you didn’t need it anymore, right?” Estevao asked Ventura.

“That wasn’t the reason why,” Ventura replied.

When prosecutors got another chance to question Ventura on re-direct examination later on Friday, she explained that she would give the money back if she could reverse Combs’ abuse. “If I never had to have freak-offs I would have agency and autonomy,” Ventura said.

After Ventura completed her testimony, her attorney, Douglas Wigdor, shared a statement from the singer: “This week has been extremely challenging, but also remarkably empowering and healing for me,” Ventura wrote. “I hope that my testimony has given strength and a voice to other survivors, and can help others who have suffered to speak up and also heal from abuse and fear. For me, the more I heal, the more I can remember, and the more I can remember, the more I will never forget.”

Another figure in the music world took the witness stand after Ventura departed Friday: Dawn Richard, whose girl group Danity Kane was launched by Combs’ MTV reality show Making the Band.

Richard has a pending civil lawsuit against Combs, in which she alleges he harassed and assaulted her during “years of inhumane working conditions.” But those claims aren’t part of the criminal trial; instead, Richard served as a corroborating witness for Ventura.

During her brief testimony, Richard told the jury she witnessed Combs physically assault Ventura on multiple occasions. In one 2009 encounter, Richard said she saw Combs punch, kick, drag and even try to hit Ventura on the head with a cooking skillet.

The trial is expected to pick up Monday (May 19) with testimony from Ventura’s longtime friend Kerry Morgan, followed by other alleged victims of Combs’ freak-offs. The jury could hear evidence for up to two months total.

The U.S. Department of Justice is conducting a criminal investigation into whether Live Nation and AEG illegally colluded in their concert refund policies at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Live Nation confirmed, though the concert giant is denying any wrongdoing.

Bloomberg first reported Thursday (May 15) that the Department of Justice (DOJ) is investigating whether Live Nation and AEG violated federal antitrust laws by coordinating their responses to mass concert cancellations via a task force when the pandemic first hit in 2020.

Prosecutors have weighed bringing charges against Live Nation and its CEO, Michael Rapino, according to Bloomberg. No such charges have yet been filed; the statute of limitations for federal antitrust prosecutions is five years, meaning that if a case is going to be brought, it will have to be soon.

Trending on Billboard

Live Nation’s regulatory chief, Dan Wall, confirmed the criminal probe in a statement to Billboard but says the company did nothing wrong.

“It is not illegal for artist agents, promoters and ticketing companies to work together to solve the unprecedented challenges of a global pandemic,” Wall says. “While Live Nation contributed to this industry effort in good faith, we set our own unique policies and refund terms to support fans and artists. We did not collude with AEG or anyone else. We are proud of our leadership during those trying times, and if any charges result from this investigation, we will defend them vigorously.”

A DOJ spokesperson declined to comment on the matter Friday (May 16). Reps for AEG did not immediately return a request for comment.

The criminal investigation comes on top of the DOJ’s civil antitrust action accusing Live Nation and its subsidiary Ticketmaster of illegally monopolizing the live music industry. The lawsuit, filed last May, seeks to break up the two live entertainment behemoths that merged in 2010.

Live Nation and Ticketmaster insist that they are in compliance with antitrust regulations and have said they plan to “vigorously defend” against the lawsuit at trial, currently scheduled for March 2026.

The Live Nation-Ticketmaster suit was brought by then-President Joe Biden’s DOJ, and Bloomberg reports that the criminal investigation into Live Nation and AEG also began when Biden was president. But both enforcement actions have continued under President Donald Trump, who has made a priority of cracking down on issues within the live entertainment business

Trump signed an executive order in March — with musician and political supporter Kid Rock in attendance — calling for greater transparency around ticket sales and directing regulators to look into possible instances of deceptive and anticompetitive conduct in the industry.

The DOJ and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) responded by launching an official inquiry into the event ticketing business on May 7. The agencies said the probe is aimed at increasing competition in order to lower ticket prices, as well as rooting out exploitative scalpers and bots.

In recent years, social media platforms have become a key battleground for copyright infringement disputes, with music rights holders targeting brands that use copyrighted tracks in social media posts.

This development can be traced, in part, to increasingly sophisticated software that major music labels and publishers use to monitor infringing uses of their songs online — a reaction to the “whack-a-mole” frustration that rights holders feel when they consistently find their songs being used on the Internet without permission. And with the risk of potential statutory damage awards for copyright infringement ranging from $200 to $150,000 per infringed work, rights holders can hold significant leverage in any ensuing legal action. Thus, whether a brand is incorporating music into posts on its social media channels or partnering with influencers who do the same, using music on social media has never been riskier.

Below, we examine the rising tide of recent lawsuits and other legal action taken against brands by music rightsholders and outline key takeaways to help avoid infringing uses and ensure that artists are properly compensated for their work.

Trending on Billboard

The Vital Pharmaceuticals Case

In 2021, UMG Recordings sued Vital Pharmaceuticals, the parent company of Bang Energy, for direct, contributory, and vicarious copyright infringement, alleging that videos posted by Bang and its influencers on TikTok used UMG’s copyrighted songs without permission. UMG argued that Bang was “well aware” that its conduct constituted copyright infringement because UMG had informed Bang of its unauthorized uses before bringing suit. UMG also argued that Bang had control over and financially benefited from its influencers’ infringing videos, which the influencers submitted to Bang for approval before posting.

Bang denied any knowledge of infringement, arguing that TikTok’s standard music license covered Bang’s use of UMG’s music. The court disagreed and granted summary judgment on UMG’s claim for direct copyright infringement, holding that UMG did not authorize TikTok to permit end users, such as Bang, to use the music for commercial (as opposed to personal) purposes. The court reasoned that because direct liability for copyright infringement does not require proof of intent, Bang’s belief that TikTok gave it permission to use UMG’s music was, at most, relevant to the amount of damages Bang owed, not whether it was liable for copyright infringement in the first instance.

The court ruled against UMG, however, on its vicarious and contributory infringement theories related to Bang’s influencers, concluding that UMG failed to prove that Bang had input regarding the selection of music included in influencers’ videos and did not point to any evidence that Bang received a direct financial benefit from the influencers’ videos.

The Growing Litigation Trend

Since UMG v. Vital Pharmaceuticals, music rights holders have ramped up enforcement efforts against other brands. Sony Music Entertainment launched its own copyright infringement lawsuit against Bang (as did Warner Music Group) and also filed claims against brands such as Gymshark, OFRA Cosmetics, Marriott International and the University of Southern California. In each case, the brands, and/or the influencers they hired, allegedly used Sony-owned sound recordings in posts promoting the companies’ products or services.

Similar to UMG’s argument in Vital Pharmaceuticals, Sony argued that each of the companies knew that their content infringed Sony’s copyrights prior to the lawsuits, and thus that the infringement was “willful,” entitling Sony to statutory damages as high as $150,000 per infringed work. In the Gymshark case, as in Vital Pharmaceuticals, it was alleged that Gymshark knew that the music was unlicensed because Gymshark previously approached Sony to discuss music licensing and then proceeded to use Sony’s music without securing commercial licenses. OFRA allegedly failed to take down infringing content after Sony sent a cease-and-desist letter and then posted new infringing content after learning of Sony’s claims. And Marriott allegedly did not take down its posts upon Sony’s request, was previously sued in 2021 for similar copyright infringement issue, and generally knew how to enter into music licenses.

As in Vital Pharmaceuticals, Sony also brought claims against alleged infringers, such as Gymshark and OFRA, for contributory and vicarious liability based on their influencers’ infringing content. Most recently, Warner Music Group (WMG) sued Crumbl and Designer Brands Inc., the parent company of DSW Shoe Warehouse, under similar theories.

While a number of these cases were just recently filed, and others ultimately settled out of court or appear to be moving towards settlement, there is no question that they are part of a fast-growing trend, and provide a glimpse into the mindset, and tactics, of rights holders with respect to unauthorized music use on social media platforms.

Navigating Platform Music Licenses

So what can brands do to avoid this type of legal action and ensure from the outset that artists are properly compensated for their copyrighted works? The best way to avoid copyright infringement when using music owned by a third party is, of course, to license the music directly from the third-party rights holders. This approach is often impractical, however, given the speed and volume with which brands need to publish content on social media.

Instead, many brands use music from the social media platforms’ respective “commercial music libraries” or “CMLs,” which contain different music options than those available for “personal” accounts. The CMLs, such as Meta’s Sound Collection and TikTok’s Commercial Music Library, allow companies and individuals to use music on the platform specifically for commercial purposes, so long as the brand also adheres to the platform’s other license terms.

Using CMLs can pose challenges, however, especially with respect to registering “business” accounts within each platform. Even with the proper registration, it is not always clear which music within the different libraries’ business or commercial accounts can use, and the scope of those rights may (and do) change over time. There are, however, a number of strategies brands can use to help ensure they are using permitted music.

For example, before using a platform’s CML, brands should review the CML’s terms of service and related policies, including terms that specify which commercial purposes the music can be used for and whether the songs can be used in videos on other platforms. It is equally important for brands to actively track the platforms’ evolving license terms in order to remain compliant. And for some brands, it may make sense to use software or external vendors to monitor and flag their brand and influencer posts for potential copyright violations across social media platforms. Of course, every brand’s business needs will be different. The key is finding the right combination of internal and external resources to help minimize the risk of copyright infringement.

Conclusion

The rising chorus of lawsuits from music rights holders is nothing to tune out. Brands using music as part of their social media strategies (which, practically speaking, is almost every brand) must take proactive steps to mitigate legal risks, and they will also be protecting artists’ rights in the process. This includes complying with and staying informed about changes to platform-specific licensing terms, ensuring that their influencers stay within the bounds of such terms, and considering tools to monitor, flag, and remove potentially infringing content. Failing to take these precautions can lead to costly litigation, reputational damage, and the forced removal of content.

Sarah Moses is an entertainment litigation partner with Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP and focuses her practice on a variety of complex litigation and commercial disputes. She represents media, entertainment and technology clients in copyright, trademark, right of publicity, First Amendment, blockchain and artificial intelligence (AI) matters, among others.

Monica Kulkarni is an advertising, marketing and media associate with Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP. She represents clients across a variety of industries and provides multidisciplinary legal counseling on transactional, compliance and regulatory matters in advertising, entertainment and media.

Jacob Geskin is a law clerk with Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP based in the Firm’s New York office where he works across music, intellectual property and media law.

Legendary rappers Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. might have been rivals in life, but they’re now united in copyright litigation.

A pair of photographers who snapped separate photos of the late hip-hop stars are teaming up to sue Univision for copyright infringement, accusing the broadcaster of using the images without permission in a web article about “Unsolved” murders.

“Plaintiffs sent a letter to Univision, demanding that it cease and desist all publication and display of the Subject Photographs,” write lawyers for the photographers in their Wednesday suit. “Univision has failed to meaningfully respond, necessitating this action.”

The case was filed by the estate of Chi Modu, a well-known hip hop photographer, over a black and white picture of Biggie looking into the camera in his trademark Coogi sweater and sunglasses; and by Dana Lixenberg, another acclaimed photog who has snapped pictures of Iggy Pop and Steely Dan, over an image of Pac in a bandana and sports jersey.

Trending on Billboard

Attorneys for Modu’s estate and Lixenberg say Univision stitched the images together and used them as art for a 2018 article reporting that a trailer had been released for a USA Network documentary series called Unsolved: The Murders of Tupac and The Notorious B.I.G.

Though Biggie and Tupac have both been gone for nearly 30 years, Wednesday’s lawsuit is just one of many recent intellectual property battles over the two iconic rappers.

Modu’s estate filed one of them, suing Universal Music Group in 2022 for allegedly using a Tupac photo in a blog post. Then last year, Shakur’s own estate threatened to sue Drake for using an AI-generated version of the later rapper’s voice. And in February, Biggie’s estate filed a lawsuit against Target, Home Depot and other retailers over allegations that they sold unauthorized canvas prints of the famed “King of New York” photo. Coogi even got in on the action in 2018, suing the Brooklyn Nets after they released a multi-colored jersey that were “inspired by Biggie” and paid homage to the Brooklyn-born rapper.

In one case, Biggie’s estate sued Modu himself, claiming the photographer had illegally authorized the use of his photos on commercial products like skateboards and shower curtains. In 2022, a year after the famed photographer passed away, a judge ruled that such merch likely violated the rapper’s likeness rights. The case ended in a settlement last year.

Reps for Univision did not immediately return a request for comment on the new lawsuit on Friday.

Free music streaming service AccuRadio has filed for bankruptcy, citing $10 million in debts to SoundExchange and failed settlement talks in the organization’s lawsuit against the streamer over unpaid artist royalties.

AccuRadio, an ad-supported platform that describes itself as “the only online music streaming service curated by human beings, not algorithms,” sought bankruptcy protection in a Wednesday (May 14) petition to the federal court in its home city of Chicago.

The bankruptcy petition says AccuRadio owes $10 million to SoundExchange, the nonprofit that collects and distributes royalties to record labels and artists. SoundExchange sued AccuRadio last summer, alleging the streamer had an undisclosed amount of unpaid royalties dating back to 2018.

Trending on Billboard

AccuRadio contests those claims, saying it’s been a “consistently reliable SoundExchange licensee for the vast majority of the past two decades.” The company put out a press release Wednesday, blaming its bankruptcy on failed settlement talks in the litigation.

“We were led to believe that our latest proposal would be accepted by SoundExchange with only minor modifications,” wrote AccuRadio’s founder/CEO, Kurt Hanson. “However, eventually SoundExchange altered its position and rejected that proposal. We were extremely disappointed that we couldn’t reach a negotiated settlement.”AccuRadio’s bankruptcy petition says the company has less than $1 million in assets, while its liabilities total $10.5 million. In addition to the $10 million SoundExchange debt, AccuRadio says it owes more than $400,000 to royalty collectors BMI and ASCAP.

The streaming service has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. This means that rather than fold completely, AccuRadio hopes to restructure, pay off its debts and continue operations in the future.

“Filing for bankruptcy protection wasn’t an easy decision, especially since our revenues have been consistently improving and we have returned to profitability,” says Hanson in the AccuRadio press release. “But we are confident that AccuRadio will emerge from it healthier and more resilient and will continue to be an outlet for human-curated music that our listeners desire and cherish.”

AccuRadio has been around since 2000. According to the company, it offers more than 1,400 ad-supported, curated music channels free of charge.

Sean “Diddy” Combs‘ ex-girlfriend Cassie Ventura faced cross-examination Thursday (May 15) from defense attorneys, who showed jurors huge numbers of her emails and text messages in an effort to prove she was a willing participant in so-called “freak-off” sex shows.

Ventura, an R&B singer who dated Combs for 11 years, is at the very core of the case against him, in which prosecutors say Combs physically abused her and coerced her to partake in the freak-offs — drug-fueled sex with male escorts for his entertainment.

After two days of direct testimony in which Ventura told jurors that she felt she had no choice but to take part, she took the stand Thursday to face questions from Combs’ lawyer Anna Estevao, according to the Associated Press and the New York Times.

Trending on Billboard

Much of the day was spent asking Ventura about emails and texts to and from Combs — some romantic, others sexually graphic. In one, she told Combs she was “always ready to freak off”; in another, she told him, “Wish we could have fo’d before you left.”

“Yes, at the time, I wanted to make him happy,” Ventura said at one point.

Combs was indicted in September, charged with running a sprawling criminal operation aimed at facilitating the freak-offs — elaborate events in which Combs and others allegedly coerced Ventura and other victims into having sex with escorts while he watched and masturbated. Prosecutors also say the star and his associates used violence, money and blackmail to keep victims silent and under his control.

It was Ventura’s civil lawsuit, filed in November 2023, that first raised allegations against Combs. Her case, which accused the star of rape and years of physical abuse, was quickly settled with a large payment from Combs, but it sparked a flood of additional suits from other alleged victims and set into motion the criminal probe that led to his indictment.

At opening statements on Monday (May 12), defense attorneys told jurors that Ventura and other women had consensually taken part in the sex parties. They admitted that Combs had committed domestic violence during their “toxic” relationship and had unusual sexual preferences, but that he had never coerced her into participating in his “swinger” lifestyle.

In questioning Cassie on Thursday, Estevao seemed intent on establishing that both she and Diddy had planned the elaborate events: “I’m too excited,” Ventura told Combs in one message from 2017, near the end of their long relationship.

When asked about those texts, Cassie seemed to push back on that suggestion, saying the things she said in the texts were “just words at that point.” That echoes her testimony from earlier in the week, in which she said the freak-offs left her feeling “humiliated” and “disgusting” but that she felt compelled to keep doing them.

The questions also focused on the complexity of Ventura’s relationship with Combs, including messages that seemed to show a loving relationship between the pair. In one, from 2010, she wrote: “Going to sleep now so it can be tomorrow faster and you can be home. Love you!!!”

Ventura confirmed as much in her answers: “I had fallen in love with him and cared about him very much.” She also admitted that she sometimes felt jealousy toward Combs over his numerous other romantic partners — another key message that the defense is seeking to relay to jurors about the couple’s relationship.

Ventura is expected to complete her testimony on Friday (May 16). After that, prosecutors will continue to call other witnesses, including a second alleged freak-off victim identified by the pseudonym “Jane” and an alleged employee victim identified by the pseudonym “Mia.” According to NBC News, prosecutor Maurene Comey said that Dawn Richard, formerly a member of the Combs-formed girl group Danity Kane who sued him for abuse in September, was expected to testify next. Defense attorneys will then have a chance to call their own witnesses. A verdict is expected by July 4.

The housekeepers suing Smokey Robinson for sexual assault have now filed a police report, leading the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to open a criminal investigation on top of the bombshell civil claims filed against the 85-year-old Motown legend.

Lawyers for four anonymous housekeepers, who alleged in a $50 million lawsuit earlier this month that William “Smokey” Robinson Jr. repeatedly raped them over the course of nearly two decades, confirm in a Thursday (May 15) statement to Billboard that criminal authorities are probing the claims.

“We are pleased to learn that the LA County Sheriff’s Department has opened a criminal investigation into our clients’ claims of sexual assault against Smokey Robinson,” say attorneys John Harris and Herbert Hayden. “Our clients intend to fully cooperate with LASD’s ongoing investigation in the pursuit of seeking justice for themselves and others that may have been similarly assaulted by him.”

Robinson’s lawyer Christopher Frost says in his own statement to Billboard that the housekeepers’ claims are “manufactured “ and motivated by “unadulterated avarice.” Frost notes that police did not launch a criminal probe unilaterally; rather that the Sheriff’s Department is required to investigate because the women filed a police report.

“We welcome that investigation, which involves plaintiffs who continue to hide their identities, because exposure to the truth is a powerful thing,” Frost says. “We feel confident that a determination will be made that Mr. Robinson did nothing wrong, and that this is a desperate attempt to prejudice public opinion and make even more of a media circus than the Plaintiffs were previously able to create.”

The Sheriff’s Department did not immediately return a request for comment Thursday.

Robinson, who’s currently on a legacy tour celebrating the 50th anniversary of his album A Quiet Storm, was accused in the May 6 civil lawsuit of forcing housekeepers to have oral and vaginal sex in his Los Angeles-area bedroom dozens of times between 2007 and 2024.

The singer’s wife, Frances Robinson, is also named in the lawsuit. The housekeepers say she did nothing to stop her husband’s abuse, despite knowing that he had a history of sexual misconduct and had previously struck settlements with assault victims.

The lawsuit also says the Robinsons paid their employees below minimum wage, and that Frances Robinson created a hostile work environment replete with screaming and “racially-charged epithets.”

Smokey and Frances Robinson have fiercely denied the housekeepers’ claims, saying through Frost on May 7 that the “vile, false allegations” are merely “an ugly method of trying to extract money from an 85-year-old American icon.”

A judge has quickly shut down an attempt by Justin Baldoni’s attorney to use the It Ends With Us litigation docket to accuse Blake Lively of extorting Taylor Swift, saying the filing is improper and “transparently invites a press uproar” without providing any relevant information for the federal court case.

The order, which came down from Judge Lewis J. Liman on Thursday (May 15), strikes Baldoni lawyer Bryan Freedman’s letter from just one day earlier in which he claimed that an unnamed source told him Lively had asked Swift to delete text messages and threatened to release private communications unless the pop star voiced public support for her sexual harassment and retaliation claims against Baldoni.

Lively’s legal team was quick to deny the allegations as “categorically false” and “completely untethered from reality,” saying such claims have no place on the court docket. Judge Liman agreed a few hours later, writing that Freedman’s letter “is improper and must be stricken.”

Trending on Billboard

“The sole purpose of the letter is to promote public scandal by advancing inflammatory accusations, on information and belief, against Lively and her counsel,” the judge wrote. “It transparently invites a press uproar by suggesting that Lively and her counsel attempted to ‘extort’ a well-known celebrity. Retaining the letter on the docket would be of no use to the court.”

Judge Liman wrote that under governing case law from the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, federal court dockets should not be “co-opted” to “promote scandal arising out of unproven, potentially libelous statements.”

“Counsel is advised that future misuse of the court’s docket may be met with sanctions,” Judge Liman wrote.

Lively’s representatives celebrated the decision Thursday, with a spokesperson for the actress saying in a statement, “It took the court less than 24 hours to see through Mr. Freedman’s irrelevant, improper and inflammatory accusations, strike them, remove them from the court and warn Mr. Freedman that further misconduct may be met with sanctions.”

Freedman did not immediately return a request for comment on the ruling.

Swift’s reps have not commented on the Lively extortion accusations, but they forcefully criticized Baldoni last week for dragging the pop superstar into the It Ends With Us litigation by way of a subpoena.

“The connection Taylor had to this film was permitting the use of one song, ‘My Tears Ricochet,’” said Swift’s spokesperson at the time. “Given that her involvement was licensing a song for the film, which 19 other artists also did, this document subpoena is designed to use Taylor Swift’s name to draw public interest by creating tabloid clickbait instead of focusing on the facts of the case.”

Lively alleges in the case that Baldoni, her co-star and director on the movie released last summer, sexually harassed her on set and then orchestrated a public relations smear campaign to retaliate against her after she complained.

Swift was brought into the fray when Baldoni countersued Lively for defamation and claimed that the actress leveraged her relationship with a “megacelebrity friend,” presumed to be Swift, to bully her way into more control of It Ends With Us.

Baldoni’s legal filing included text messages concerning an alleged meeting attended by “Ryan and Taylor,” seemingly referencing Swift and Lively’s husband, Ryan Reynolds. In one message sent by Lively, the actress called Swift and Reynolds her “most trusted partners” and compared them to the “dragons” in the show Game of Thrones.

“The message could not have been clearer,” Baldoni’s lawyers wrote in the countersuit. “Baldoni was not just dealing with Lively. He was also facing Lively’s ‘dragons,’ two of the most influential and wealthy celebrities in the world, who were not afraid to make things very difficult for him.”

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio