Forever No. 1

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor Brian Wilson, who died on Wednesday (June 11) at age 82, by looking at the second of The Beach Boys’ three Hot 100-toppers: “Help Me, Rhonda,” the final classic of the Beach Boys’ earliest golden age.

What a difference an “h” makes. When “Help Me, Ronda” was originally featured on The Beach Boys Today! in early 1965, the band didn’t think too much of the shuffling love song with the repetitive hook; you can tell by how little care they took to normalize the volume levels, which inexplicably jump around in the song’s last two choruses. But leader Brian Wilson believed in the song’s potential, and after the band re-recorded it or single release (and for inclusion on the band’s second 1965 album, Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!)) as “Help Me, Rhonda,” it became the latest in a stunning streak of smashes for the family-and-friends quintet from Southern California.

Trending on Billboard

In fact, by early 1965, The Beach Boys was one of the only American bands still holding its own against the pop-rock raiders from overseas. The British Invasion was in full swing, and The Beatles alone had topped the Hot 100 six times in 1964. In between No. 1s four and five for the Fab Four that year came the Boys’ eternal teen anthem “I Get Around” and the group had two additional top 10 hits by the end of ’64: the wistful “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” (No. 9) and the the ebullient “Dance, Dance, Dance” (No. 8). Both of those were included on The Beach Boys Today! at the top of 1965, and the set also spawned a third single in a cover of Bobby Freeman’s “Do You Wanna Dance?,” which just missed the top 10 (No. 12) that April.

As the Beach Boys were still enjoying their run of fun-and-sun early hits, Brian Wilson was beginning to stretch out both as a songwriter and a producer. “I Get Around” was backed by “Don’t Worry Baby,” Wilson’s first real attempt to outdo his idol Phil Spector, with impossibly dreamy production and harmonies and a gorgeous rising verse melody that somehow elevated into an even-higher-flying chorus. The flip-side to “Dance, Dance, Dance” was “Please Let Me Wonder,” another Spectorian love song with strikingly fragile verses and a near choir-like refrain. And perhaps most notably, Today! included the lovely but disquieting “She Knows Me Too Well,” Wilson’s first real lyrical examination of his own romantic insecurities and failings. All of these would ultimately point the way to the artistic leap forward the band would take on 1966’s Pet Sounds, the band’s intensely personal and overwhelmingly lush masterwork which disappointed commercially, but made them critics’ darlings for the first time.

But they weren’t there yet. In mid-’65, they were still fighting to maintain their place in an increasingly crowded pop-rock landscape — and, not having reached the Hot 100’s top five since “I Get Around” nearly a full year earlier, they needed a no-doubter to lead off Summer Days. So Brian Wilson dug back in on the song he’d relegated to deep-cut status on the album before. “Ronda” was much more in line with the group’s earlier, simpler hits than the more lyrically and musically complex fare Wilson was starting to explore, but he was right that the song had real potential: It was a clever number that basically managed to be both a breakup ballad and an upbeat love song at once, with a chorus so relentless that you could hear it once and remember it for the rest of your life. It just needed a little extra maintenance.

In truth, Brian did a lot more on the re-recording of “Help Me, Ronda” than add an “h” to her name and keep his finger steadier on the volume controls. He also clipped the intro, so it began right with its “Well, since she put me down…” intro, dropping you right into the middle of the song’s narrative. He tightened the tempo a little, and added some “bow-bow-bow-bow” backing vocals to tie together the “help-help me, Rhonda” pleas of the chorus. He added some extra piano and guitar to give the song’s instrumental bridge a little extra zip. And perhaps most importantly, he laid an extra falsetto backing “Help me, Rhonda, yeah!” on top of the chorus climax to make it stand out a little better from the rest of the refrain. They’re all small additions, but you don’t realize how much difference they make until you go back to the Today! original and wonder why the whole thing sounds so empty and lifeless by comparison.

But while Brian Wilson allowed the song to soar, “Rhonda” was anchored by a less-celebrated Beach Boy: Al Jardine. A high school friend of Brian’s, Jardine had mostly served as a glue guy in the band to that point and had never sung lead on one of their songs, much less a single A-side. But Brian was intent on giving his buddy a spotlight moment, and decided Jardine would take the reins for “Rhonda.” It was a good match: While the Wilsons’ voices drifted towards the ethereal and sentimental, and Mike Love’s had a more muscular, occasionally snide edge to it, Al Jardine’s voice had both a sturdiness and an unassuming everyman quality to it. He was the Beach Boy best equipped to sell a relatable song like “Rhonda.”

And while “Rhonda” was a less musically and lyrically ambitious song than others Wilson was attempting contemporaneously, there is still a bit of trickiness to it. It’s a lyric that mourns a romantic split with one girl while attempting to simultaneously ask a new girl to ease his pain — and the vocal matches the shift; Jardine’s singing is frenzied and pained and in the first half of his verses and smooth and composed in the second. From a less likable or compelling vocalist, the whole thing could’ve very easily come off like a cheap come-on, like he doesn’t actually give a damn about either girl. But Jardine manages to sound sincere, like he actually is going through it and is genuinely in need of the help that only the titular female can provide. When he begs on the chorus for Rhonda to “get ‘er outta my heart!” — after a couple dozen shorter pleas from the rest of the Boys — you really hope she succeeds in doing so.

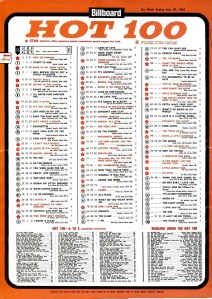

With its new arrangement and new title, “Rhonda” did indeed prove the no-doubter that the Beach Boys were hoping for to re-establish their pop supremacy in ’65. The song debuted on the Hot 100 on April 17 at No. 80, and seven weeks later, it replaced — who else — The Beatles’ “Ticket to Ride” to become the band’s second No. 1 hit, lasting two weeks on top before being replaced by the other dominant American pop group of the era: The Supremes, with “Back in My Arms Again.” The Beatles would, of course, be heard from again just a few months later with a “Help!” No. 1 of their own — and in between them in June, the Four Tops reigned with “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch).” (Draw your own conclusions about a generational cry for additional assistance amidst the turmoil of the mid-’60s if you so desire.)

Billboard Hot 100

Billboard

“Help Me, Rhonda” would mark something of the end of an era for The Beach Boys and Brian Wilson, as it was their last major pop hit before the group started rapidly scaling up its ambitions. Even “California Girls,” the group’s universally accessible No. 3-peaking follow-up to “Rhonda” — which, wouldn’t you know it, got stuck behind The Beatles’ “Help!” on the Hot 100 — came affixed with a cinematic instrumental intro and a vocal outro in-the-round that no other pop group of the time would have dared attempt. By 1966, the group was pushing pop music into the future at a rate that would ultimately prove uncomfortable for both the public and for the Beach Boys themselves — though it would culminate in one more all-time classic pop single before it all fell apart.

And “Help Me, Rhonda” stands alone in all of pop history in at least one respect: It remains the lone Billboard Hot 100 representation for all Rhondas worldwide. No other song (or artist) with that name — outside of a No. 22-peaking Johnny Rivers cover of the song in 1975, featuring Brian on backing vocals — has ever reached the chart since its 1958 introduction. (No “Ronda”s either.)

Tomorrow, we look at the final of the Beach Boys’ three Brian Wilson-led No. 1s: the forever singular “Good Vibrations.”

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor Brian Wilson, who died on Wednesday (June 11) at age 82, by looking at the first of The Beach Boys’ three Hot 100-toppers: the irresistible pop smash “I Get Around.”

The Beach Boys had racked up four consecutive top 10 hits on the Billboard Hot 100 (discounting B sides) prior to “I Get Around,” but this ebullient song was their first single to reach No. 1. They recorded it in April 1964, making it the first song they recorded after The Beatles arrived in the U.S. that February.

Trending on Billboard

If The Beach Boys felt threatened by the Fab Four’s explosive arrival, they were not going down without a fight. “I Get Around” is chock-full of hooks – great harmonies, handclaps, twangy guitar work and the inspired “round-round-getaround” hook.

In his liner notes for the 1990 reissue of Little Deuce Coupe and All Summer Long, Beach Boys expert David Leaf said the track represented “a major, revolutionary step in Brian’s use of dynamics.” He added: “From the opening note to the falsetto wail on the fade, this is one of the greatest tracks the Beach Boys ever cut. … Powered by the driving lead guitar break, the explosive harmonies and the handclaps, everything about this track was very spirited.”

The song runs a highly efficient 2:14, making it the second-shortest No. 1 hit of 1964. The Beatles’ “Can’t Buy Me Love” was a couple of seconds shorter.

With this song, The Beach Boys continued to move away from the surf music fad that they rode in on, with such hits as 1962’s “Surfin” and “Surfin’ Safari” and 1963’ “Surfin’ U.S.A.” and “Surfer Girl.” Like its immediate predecessors “Be True to Your School” and “Fun, Fun, Fun,” “I Get Around” has nothing to do with catching a wave, but instead is more generally capturing teen life in early-’60s California. (And, when you think about it, driving songs played nearly as big a part of the early Beach Boys success as surfing songs, between “I Get Around,” “Fun, Fun, Fun,” “Little Deuce Coupe,” “409” and others.)

Mike Love sang lead vocals on “I Get Around,” with Brian Wilson contributing falsetto lead vocals on the chorus. All five members of the group – also including Al Jardine, Carl Wilson and Dennis Wilson – contributed harmony and backing vocals. The fabled Wrecking Crew of top Los Angeles session players, including Hal Blaine and Glen Campbell, played on the track.

The song has a line that seems autobiographical, given the group’s rising level of success over the previous two years: “My buddies and me are gettin’ real well-known.” The song also includes one of the most charming lines ever in a pop song: “None of the guys go steady ’cause it wouldn’t be right/ To leave your best girl home on a Saturday night.”

The group projects a strutting confidence throughout. Biographer Mark Dillon compared the lyrics to “the braggadocio of a modern-day rapper” — fitting that nearly 30 years later, one of the all-time most legendary MCs would recycle the title for his own cockiest hit.

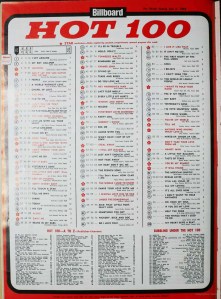

The song entered the Hot 100 at No. 76 for the week ending May 23, 1964. It was the week’s fourth-highest new entry, behind hits by Elvis, Bobby Vinton and Lesley Gore, though it wound up eclipsing all of those. The song reached No. 1 in its seventh week, July 4, displacing Peter & Gordon’s “A World Without Love,” which was written by Paul McCartney (though officially credited to Lennon/McCartney.)

Billboard Hot 100

Billboard

McCartney and Wilson, two of the greatest songwriters of all time, spurred each other on to ever-greater heights for many years. The Beatles’ “Back in the U.S.S.R.” was clearly an homage to The Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ U.S.A.”

“I Get Around” topped the Hot 100 for two weeks, before being displaced by The 4 Seasons’ “Rag Doll.” (These groups, representing the pinnacle of West Coast and the East Coast pop, respectively, were among the few American groups from the pre-Beatles era that continued to thrive after the British invasion.) “I Get Around” also put The Beach Boys on the map in the U.K., becoming their first top 10 hit in that country.

The B side of “I Get Around” was the equally great “Don’t Worry Baby,” making this one of the strongest double-sided singles in pop music history. It ranks with Elvis’ “Don’t Be Cruel”/ “Hound Dog,” The Beatles’ “Penny Lane”/“Strawberry Fields Forever,” The Beach Boys’ own “Wouldn’t It Be Nice”/“God Only Knows” and a handful of others.

The song was the opening track on (and only single released from) the group’s sixth album, All Summer Long, which reached No. 4 on the Billboard 200 in August 1964. In his liner notes to the 1990 reissue, Leaf noted, “All Summer Long was the last regular studio album The Beach Boys recorded before Brian quit the touring band – the last complete Beach Boys album Brian cut before he suffered a nervous breakdown in late December of 1964.”

Incredibly, “I Get Around” didn’t receive a single Grammy nomination. The Beach Boys’ only songs to receive Grammy nods were “Good Vibrations” and the 1988 Brian-less hit “Kokomo.” The Recording Academy has since sought to make amends, awarding The Beach Boys a lifetime achievement award in 2001 and inducting five of their most classic works (including “I Get Around”) into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Wilson was initially the only songwriter credited on the song. In 1992, Mike Love sued to get a credit on this and many other songs. Love prevailed in December 1994, when he was awarded co-writing credits on 35 songs – as well as $13 million. In his series “The Number Ones,” Stereogum writer Tom Breihan wryly summarized the dispute: “Mike Love later sued Brian for a co-writer credit, and if he really did come up with the round round getaround part, he deserved it.”

While there is no improving on The Beach Boys’ recording of “I Get Around,” several artists have taken a stab at it over the years. Red Hot Chili Peppers performed it at the 2005 MusiCares Person of the Year gala where Brian Wilson was honored. My Morning Jacket performed it on the 2023 special A Grammy Salute to the Beach Boys (which CBS re-aired on Sunday night).

Billie Joe Armstrong posted his version of the song on Instagram on Wednesday (June 11), hours after the news of Wilson’s death broke. “Thank you Brian Wilson,” Armstrong wrote. “I recorded a cover of ‘I Get Around’ a few years ago. ..never got to share it. One of my all time favorite songs ever.”

Check back tomorrow and Wednesday for our Forever No. 1 reports on The Beach Boys’ second and third No. 1 hits, “Help Me Rhonda” and “Good Vibrations.”

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor Sly Stone, who died on Monday (June 9) at age 82, by looking at the final of Sly & the Family Stone’s three Hot 100-toppers: the joyous but fractured “Family Affair.”

True to its name, Sly & the Family Stone had been the ultimate musical family affair. Of course, it literally comprised multiple siblings — Sly Stone (originally Sylvester Stewart) was of course the band’s brilliant leader and de facto frontman, while brother Freddie sang and played guitar, sister Rose sang and played keys, and sister Vet even occasionally filled in for Rose on tour. But it was the band’s familial spirit that originally sparked its jump-off-the-stereo brilliance, a palpable sense of shared love, excitement and unity. The on-record and on-stage product reflected the band’s real-life late-’60s closeness, as a Bay Area-based unit that happily did everything together: In 2025’s Questlove-helmed Sly Lives documentary, the group waxes nostalgic about how they’d all ride bikes together, watch movies together, even buy dogs together. “I think we spent more time together than we spent with our family members,” recalled trumpeter and singer Cynthia Robinson.

Trending on Billboard

By 1971, the band was decidedly no longer doing everything together, and much of what they did was less than happy. As the band became superstars in 1969, and Sly Stone one of the leading voices and faces of popular music, internal pressures and tensions mounted, outside demands intensified both about their recorded output and their political positioning, and Sly began to retreat. He moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles, self-medicated heavily with drugs, came late to gigs or no-showed altogether, and generally began to isolate himself from the rest of the group. The group’s final single of the ’60s, the double-A side “Thank You Falettin Me Be Mice Elf Agin”/”Everybody Is a Star,” had been a 1970 No. 1 hit, but already displayed a growing disillusionment with the skyrocketing success of the band’s Stand! and “Everyday People” days. It would be the previously prolific outfit’s final release for nearly two years.

When Sly & the Family Stone returned in late 1971, it was with “Family Affair,” an R&B gem that was at once of a piece with the celebratory pop-soul anthems the group had made his name with, and sounded like a different outfit altogether. Though the song still felt warm, soothing and hooky as hell, the group’s earlier spirit of triumph, jubilation, defiance, energy and above all, togetherness, had largely disappeared. Even “Thank You,” for all its creeping darkness, still felt like the band was all in the fight together; by “Family Affair,” they barely sounded like a band at all.

In fact, the most bitterly ironic thing about “Family Affair” — which served as the lead single from that November’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On LP — is that Sly is the only member of the Family Stone to actually play on it. (Probably, anyway; the Riot sessions were so messy and hazy that no one seems 100% positive of exactly who did what.) Rose does sing the song’s iconic chorus, but instrumentally, the song is nearly all Sly, with additional electric piano by star keyboardist Billy Preston and some guitar croaks from rising soul hitmaker Bobby Womack. The Family Stone’s leader most likely provided the rest, including all the verse vocals, bass and additional guitar.

The final instrument played by Stone on the track was the newest and perhaps most important to the musical direction of “Affair” and Riot in general: the Maestro Rhythm King MRK–2. Drummer Greg Errico had gotten fed up with the discord within the group and left earlier in ’71 midway through the Riot recording; rather than immediately replace him with a new stickman, Stone decided to fill out the remaining tracks with the rudimentary early drum machine and its genre presets. But he allowed the machine to work for his purposes by essentially slotting its canned bossa nova rhythm askew within the song’s groove — like J Dilla might have done decades later — giving the liquid-funk shuffle of “Family Affair” a little extra slipperiness. Even Errico, with every reason in the word to take offense at essentially being replaced by an underqualified robot, had to give it up to the bandleader for his innovation: “[He] took the rhythm that [the machine] was producing and turned it inside out,” the drummer raved in Sly Lives! “It made it, ‘Oh, that’s interesting now.’ And he actually crated an iconic thing with it. It became a game-changer again.”

Sly & the Family Stone, Forever No. 1: “Everyday People” (1969) / “Thank You Falettin Me Be Mice Elf Agin” (1970)

The song’s untraditional groove was matched by a near-unrecognizable Sly Stone vocal that almost felt like just another instrumental texture. Previous records had featured his clear vocal piercing through his productions with shout-along sentiments, or as one voice among many in delivering strength-in-numbers statements. This was new: a heavily filtered Stone seemingly singing from a remote corner of the studio, feeling more like a disembodied narrator than a leading man. What’s more, his singing register had dropped, as if he’d aged multiple decades (or gone through a second puberty) in between Stand! and Riot, with the result landing Stone somewhere between crooning and sing-speaking.

The vocals were jarring, but so were the lyrics. In 1969, a “Family Affair” would be an occasion for joy and revelry, but by 1971, it was a little more complicated — and the family portrait painted by Stone was of a largely dysfunctional unit, with siblings who head in different directions, newlyweds with maybe-straying eyes, and fraught emotions running high all around. “You can’t leave ’cause your heart is there/ But, sure, you can’t stay ’cause you been somewhere else,” Stone sings of his own conflicted feelings in the song’s most revealing passage. “You can’t cry ’cause you’ll look broke down/ But you’re cryin’ anyway ’cause you’re all broke down.”

But downers don’t usually become No. 1 hits — and indeed, despite the heavy dynamics of this “Family Affair,” the ultimate feeling is still more one of welcoming than of alienation. Partly, that’s because of the gleeful boogie Preston’s plush keys and Sly’s aqueous guitars do around the song’s rain-slicked beat, and largely, that’s because Rose’s “It’s a family affaaiiiiii-iiiiirrrr…” callouts — the first vocals of any kind you hear in the song — are so comforting and inviting that it can’t help but rub off on the rest of the song. But it’s also because, even with Sly’s clearly mixed feelings about his own place within the family, he still feels audibly connected to it; it’s a complex relationship, but still a loving one at heart. “Blood’s thicker than the mud,” he proclaims early in the song, and despite everything, he sounds like he means it.

Unfortunately, the Family Stone had already begun to splinter. Errico was the first out the door, the next year, bassist Larry Graham followed. As the band began to lose its center and as Sly’s productivity and reliability both stalled, so did its commercial success: the long-awaited There’s a Riot Goin’ On topped the Billboard 200 and is hailed today as a classic (despite drawing mixed reviews at the time for its murky production and disjointed jams), but “Family Affair” was its only single to even reach the Hot 100’s top 20. Fresh, released in 1973, saw the band returning to greater accessibility, and kept up its streak of classic lead singles with the slithering “If You Want Me to Stay.” But even that song missed the top 10, and as acolytes like the Ohio Players and Parliament-Funkadelic had replaced the band at funk’s forefront, the Family Stone’s relevance continued to slide until officially splitting in 1975.

Considering Sly Stone was just 32 when the Family Stone dissolved for the first time, it feels both deeply sad and highly improbable that his career never really found a proper second act. But Sly’s subsequent attempts throughout the late ’70s and ’80s to launch a solo career or revive the Family Stone with a new lineup largely fell on deaf ears; even a seemingly world-stopping (or at least potentially career-re-sparking) collaborative endeavor alongside P-Funk leader George Clinton fell into disarray and resulted in an album that was mostly dismissed critically and commercially. Drug abuse continued to take its toll on an increasingly reclusive Sly, and despite sporadic reappearances over the last four decades, a true comeback was never really in the cards for the music legend.

But even if his own presence was minimal over the past half-century, the impact of Sly Stone’s music remained seismic. Outside of setting the early standard for what would become funk’s golden age in the early ’70s, the Family Stone’s catalog remained one of the most well-mined sample sources across the ’80s and ’90s for N.W.A, LL Cool J, the Beastie Boys, Cypress Hill, Beck, Janet Jackson and countless other game-changing acts. And that impact certainly endured into the 21st century: In the first couple years of the ’00s alone, D’Angelo released the massively acclaimed and heavily Riot-inspired Voodoo, while OutKast referenced that album’s bullet-ridden American flag imagery on the cover to their universally beloved Stankonia, and Mary J. Blige had a Hot 100 No. 1 with a “Family Affair” of her own. As messy as things could ever get with Sly Stone or his legacy, the blood would always remain thicker than the mud.

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor Sly Stone, who died on Monday (June 9) at age 82, by looking at the first of Sly & the Family Stone’s three Hot 100-toppers: the simple, yet profound “Everyday People.”

Sly & the Family Stone, a genre-fluid, interracial, mixed-gender group (at a time when all three things were unique) was formed in San Francisco in 1966. The group was led by Sly Stone, a musical prodigy who was just 23 at the time. His main claim-to-fame at that point is that he had produced a string of hits for the pop/rock group The Beau Brummels, including “Laugh, Laugh” and “Just a Little.”

Trending on Billboard

Sly & the Family Stone made the top 10 on the Billboard Hot 100 in April 1968 with its first chart hit, “Dance to the Music.” That funky celebration of dance music wasn’t topical at all, but after the stunning events of 1968 – a year of assassinations, riots and a war without end in Vietnam – acts almost had to say something, and Sly & the Family Stone did on “Everyday People,” which was released that November.

The song is a plea for understanding and racial unity, which is so understated in its approach that it’s easy to lose sight of just how progressive its sentiments seemed in 1968. The record has a gentle tone and a disarming opening line: “Sometimes I’m right and I can be wrong/ My own beliefs are in my song.” Who ever starts out a conversation by conceding “I can be wrong?”

The sense of urgency and passion picks up on the proclamation “I am everyday people!” which is repeated three times during the song, and then on the call to action “We got to live together,” which is repeated twice.

Stone, who was born Sylvester Stewart, wrote and produced “Everyday People.” His genius move on this song was to simplify the discussion to the level of a childhood playground taunt – “There is a yellow one that won’t accept the Black one/ That won’t accept the red one that won’t accept the white one/ Different strokes for different folks/And so on and so on and scooby-dooby-dooby.” The unspoken, but unmistakable, message: Isn’t all this division really pretty childish?

Sly makes the point even more directly in the second verse: “I am no better and neither are you/ We are the same whatever we do.” The reasonableness of his argument instantly disarms any detractors.

The song’s politics are expressed most directly in the third verse, in the song’s depiction of counter-culture types vs. establishment types; progressives vs. conservatives. “There is a long hair that doesn’t like the short hair/For being such a rich one that will not help the poor one.”

The bridges of the song contain the line “different strokes for different folks,” which was initially popularized by Muhammad Ali. It became a popular catchphrase in 1969 (and inspired the name of a 1978-86 TV sitcom, Diff’rent Strokes).

Sly wisely kept the record short – the childlike sections, which are charming in small doses, would have become grating if the record had overstayed its welcome. The record runs just 2:18, shorter than any other No. 1 hit of 1969.

Three Dog Night took a similar approach on “Black & White,” which was a No. 1 hit in September 1972 – putting a plea for racial unity and brotherhood in simple, grade-school language. Three Dog’s record isn’t as timeless or memorable as “Everyday People,” but it shows Sly’s influence.

“Everyday People” entered the Hot 100 at No. 93 for the week ending Nov. 30, 1968. You might assume that a record this catchy and classic shot to the top quickly, but it took a while. In the week ending Jan. 11, 1969, it inched up from No. 27 to No. 26, looking like it might not even match “Dance to the Music”’s top 10 ranking. But then it caught fire. The following week, it leapt to No. 15, then No. 5, then No. 2 for a couple of weeks behind Tommy James & the Shondells’ “Crimson and Clover,” before finally reaching the top spot in the week ending Feb. 15.

It stayed on top for four consecutive weeks, the longest stay of Sly’s career. The song was of a piece with such other socially-aware No. 1 hits as Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” (1967) and The Rascals’ “People Got to Be Free” (1968).

“Everyday People” remained on the Hot 100 for 19 weeks, a personal best for Sly, and wound up as the No. 5 song of 1969 on Billboard’s year-end chart recap. The song was included on the group’s fourth studio album, Stand!, which was released in May 1969. The album reached No. 13 on the Billboard 200 and remained on the chart for 102 weeks – also a personal best for the group. The album, which also featured “Sing a Simple Song,” “Stand!” and “I Want to Take You Higher,” was inducted into the National Recording Registry in 2014 and the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2015.

Billboard

The band included “Everyday People” in their set at Woodstock on Aug. 17, 1969. Fun Fact: It was the only No. 1 Hot 100 hit performed by the original artist during that landmark three-day festival.

The song is widely acknowledged as a classic. Rolling Stone had it at No. 109 on its 2024 update of its 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list. Billboard included it on its 2023 list of the 500 Best Pop Songs: Staff List. (We had it way down at No. 293, clearly proving the wisdom of Sly’s opening line, “Sometimes I’m right and I can be wrong.”)

While Sly was bedeviled by personal demons that shortened his run at the top, he lived to get his flowers. The band was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1993 (in its first year of eligibility). On his own, Sly received a lifetime achievement award from the Recording Academy in 2017.

Numerous artists covered “Everyday People” in the wake of Sly’s recording. Between 1969 and 1972, the song was featured on Billboard 200 albums by The Supremes, Ike & Tina Turner, The Winstons, Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band, Supremes & Four Tops, Billy Paul and Dionne Warwick.

Spend any time on YouTube and you can also find cover versions of “Everyday People” by everyone from Peggy Lee to Pearl Jam (who performed it in concert in 1995). Other artists who took a stab at it: Aretha Franklin, The Staple Singers, William Bell, Belle & Sebastian, Maroon 5 (on a 2005 remix and cover album Different Strokes by Different Folks) and the unlikely team of Cher and Future, who covered it for a 2017 Gap ad that has recently gone viral.

A couple artists even had Hot 100 hits with their new spins on the song. Joan Jett & the Blackhearts covered the song in 1983 and took it to No. 37. Arrested Development drew heavily from the song for their 1993 hit “People Everyday,” which reached No. 8. (The song used the chorus and basic structure of the original, with new verses written by lead singer Speech.)

Sly & the Family Stone nearly landed a second No. 1 hit in 1969, but “Hot Fun in the Summertime” stalled at No. 2 for two weeks in October behind The Temptations’ “I Can’t Get Next to You.” “Hot Fun” wound up at No. 7 on the aforementioned year-end Hot 100 recap, making Sly the only act with two songs in the year-end top 10.

Questlove, who directed the 2025 documentary Sly Lives (aka The Burden of Black Genius), shared a touching tribute to the icon on Instagram on Monday. “Sly Stone, born Sylvester Stewart, left this earth today, but the changes he sparked while here will echo forever … He dared to be simple in the most complex ways — using childlike joy, wordless cries, and nursery rhyme cadences to express adult truths.”

That last part was a clear reference to “Everyday People.” Questlove also recalled what he called that song’s “eternal cry” – “We got to live together!” Said Quest: “Once idealistic, now I hear it as a command. Sly’s music will likely speak to us even more now than it did then. Thank you, Sly. You will forever live.”

Later this week: Two additional Sly & the Family Stone No. 1s take the group into darker and murkier territory, with similarly spellbinding results.

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor the late Robert John with a look at his lone No. 1: The sweetly insensitive 1979 throwback smash “Sad Eyes.”

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Perhaps it made counterintuitive sense that Robert John would finally score his career-making solo ballad at one of the most inhospitable times for downtempo pop music in the history of top 40. The year 1979 was defined first and foremost by disco: the thumping dance music that not only made stars out of the Bee Gees, Chic and Donna Summer but also convinced artists as far-flung as Herb Alpert, Rod Stewart and Blondie to get on the floor. All six of those artists topped the Hot 100 with disco (or at least disco-influenced) songs in 1979, and the charts’ biggest exception to disco’s dominance — power-poppers The Knack, who ended up with the chart’s year-end No. 1 with the irresistible “My Sharona” — was still just as propulsive and beat-driven. The Hot 100 certainly should not have had room at its apex in 1979 for a song as slow-paced, winsome and unapologetically retro as “Sad Eyes.”

Trending on Billboard

But Robert John’s path on the charts had never exactly been a logical one. His career arc was atypically jagged and erratic for a pop singer, starting at an unnaturally young age and continuing for decades, but rarely for more than a hit song at a time, and often with many fallow years coming in between them. By 1979, John had technically been a hitmaker for over 20 years, but he also hadn’t reached the Hot 100 since 1972, and he had even given up on making music altogether for a stretch in the mid-decade. For him to return to recording and immediately top the Hot 100 for the first and only time in his career, with a song at about half the BPM of most of the hits surrounding it on top 40 at the time? Sure, why not.

In truth, it wasn’t like “Sad Eyes” was the only slow song making it on the radio in the late ’70s. There were still plenty of nuggets of AM gold to be found among the silver disco balls littering that era’s charts, sweetly harmonized gems like Walter Egan’s “Magnet and Steel,” Olivia Newton-John’s “Hopelessly Devoted to You” and Barry Manilow’s “Can’t Smile Without You.” Even disco stalwarts the Bee Gees kicked the year off with “Too Much Heaven,” one of the group’s most sentimental ballads, topping the Hot 100. Another such hit from the time that had just missed the top 10 in 1978, Toby Beau’s “My Angel Baby,” caught the ear of producer George Tobin, who felt a song like that would be a good fit for Robert John.

John would take some convincing. He was essentially retired from music at the time, and was working construction in New Jersey. John had become frustrated with the industry after 15 years of recording — dating back to the minor 1958 hit “White Bucks and Saddle Shoes,” which he recorded as Bobby Pedrick, Jr. when he was just 12 years old — which had failed to result in a consistently sustainable career for him. The final straw came following the success of his 1971 version of The Tokens’ Hot 100-topping 1961 smash “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” which went to No. 3 on the chart and sold over a million copies — but still didn’t inspire much belief in him from his then-label, Atlantic Records. “The company didn’t have enough faith to let me do an album,” he told Rolling Stone. “I decided that if that’s what happens after [such a big hit] then I just wasn’t going to sing anymore.”

Tobin invited John to live with him as they worked on the song that would become his comeback single. They eventually came up with “Sad Eyes,” a breakup ballad built on a plush water bed of aqueous electric piano, twinkling glockenspiel, loping bass, buoyant guitar and a crisp drum shuffle. The production was lovely without being overwhelmingly lush, and John’s mostly falsetto vocal was its perfect match — particularly towards the song’s end, when the song modulates up and John uses his doo-wop background to hit some unreal upper-register ad libs as the chorus repeats to fade.

In fact, the song was so sweet that it was easy to miss just what a cad John was playing in its lyrics. The “Sad Eyes” in question belong to a lover who John is breaking it off with, presumably because his main squeeze is returning from afar: “Looks like it’s over, you knew I couldn’t stay/ She’s comin’ home today,” he explains in the opening lines. The song’s patronizing attempts to comfort the soon-to-be-ex on the verses (“Try to remember the magic that we shared/ In time your broken heart will mend”) turn to outright selfishness on the chorus (“Turn the other way… I don’t want to see you cry”) — but they never quite feel mean-spirited enough to the point of distracting from the song’s intoxicating sway.

After a false start with Arista, Tobin and John eventually caught the interest of EMI America, launched just the year before, which released the record in April 1979. The song debuted at No. 85 on the Hot 100 dated May 19, though it didn’t top the chart until 20 weeks later — tying a Hot 100 record to that point, set the year before by Nick Gilder’s “Hot Child in the City” for longest trek to No. 1 — when it finally knocked The Knack out of the top spot after its six-week reign with “My Sharona.” (John also set a record with the longest time in between his first Hot 100 entry and his first No. 1, dating back 21 years to his “White Bucks and Saddle Shoes” debut in 1958, though Tina Turner would take that mark over a half-decade later with her “What’s Love Got to Do With It.”) “Sad Eyes” lasted just one week atop the listing, before the disco order was once again restored — as the song was unseated by Michael Jackson’s all-timer Off the Wall lead single, “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough.”

Billboard

This time, Robert John at least would get to make a full album: a self-titled LP, also released on EMI in 1979, which peaked at No. 68 on the Billboard 200 that October. But the album failed to spawn another top 40 hit — the groovier “Lonely Eyes” peaked just outside the region in early 1980 — and John would only make the chart subsequently with a trio of covers, faring the best with his No. 31-peaking take on Eddie Holman’s “Hey There Lonely Girl,” from 1980’s Back on the Street. That album would prove to be his last, and John mostly retired from recording and performing again after that.

Robert John might never have gotten the sustained success or career stability he hoped for as a singer, but he did have hits in four separate decades, he did get his name multiple times in the Billboard record books, and he can claim to be one of just a few artists in the world to rule the age of disco with a not-even-remotely-disco record. Even he eventually turned the other way, that’s nothing to be sad about.

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor Roberta Flack, who died on Feb. 24 at age 88, by looking at the singer’s second of three No. 1 hits as a recording artist: the instant standard “Killing Me Softly With His Song.” (In case you missed it, here’s a look at her first No. 1, “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.”)

Roberta Flack could have brought a book or a magazine to read on an American Airlines flight from L.A. back home to New York in 1972. She could have watched the in-flight movie or even taken a nap. Let’s all be grateful that she instead chose to listen to the in-flight audio program, which included a pretty pop/folk ballad recorded by a then-20-year-old singer named Lori Lieberman.

Trending on Billboard

Flack scanned the list of audio selections and learned that the composition, “Killing Me Softly With His Song,” was written by Norman Gimbel and Charles Fox. Gimbel was then best-known for writing English-language lyrics to such global hits as “The Girl From Ipanema” and “I Will Wait for You”; Fox for creating the sunshine pop musical backgrounds on the hit ABC show Love, American Style.

“The title, of course, smacked me in the face,” Flack later said. “I immediately pulled out some scratch paper, made musical staves [and then] play[ed] the song at least eight to 10 times jotting down the melody that I heard. When I landed, I immediately called Quincy [Jones] at his house and asked him how to meet Charles Fox. Two days later I had the music.”

By most accounts, the song was inspired by Lieberman seeing Don McLean perform at the Troubadour club in Los Angeles in November 1971. McLean’s “American Pie” entered the Billboard Hot 100 that month (on its way to No. 1 in January 1972), but Lieberman was more taken by another song in the set, the haunting ballad “Empty Chairs.” The singer jotted some notes and impressions on a napkin. She later described the experience, and how deeply it affected her, to Gimbel, with whom she was working at the time. (Gimbel and Fox had signed her to a five-year production, recording and publishing deal.)

Lieberman’s description reminded Gimbel of a phrase that was already in his idea notebook: “to kill us softly with some blues.” The phrase had appeared five years earlier in a novel by Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar and Gimbel thought it had possibilities. Gimbel drew from Lieberman’s account, crafted the lyrics, and passed them on to Fox, who set them to faintly melancholy music.

Lieberman did not receive a co-writing credit on the song. There is even a dispute over whether, and to what degree, the song was inspired by McLean’s performance. When Dan MacIntosh of Songfacts asked Fox in 2010 about the McLean origin story, Fox said: “I think it’s called an urban legend. It really didn’t happen that way.”

Lieberman had a falling out with Gimbel (who died in 2018) and Fox (who is still living at 84). This backstage drama is intriguing, but mostly irrelevant to the story of Flack’s recording, which quickly became one of the biggest and best (and most celebrated) singles of its era.

Jones, who died less than four months ago, played a key role in this story a second time. In September 1972, Flack was opening for Jones at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles. Flack was red-hot at the time, having landed million-sellers that year with the classic ballad “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” and the ebullient “Where Is the Love,” a silky duet with Donny Hathaway.

When the audience at the Greek kept cheering, Jones advised her to go back out and sing one more song. “Well, I have this new song I’ve been working on,” Flack replied. “After I finished [‘Killing Me Softly’], the audience would not stop screaming. And Quincy said, ‘Ro, don’t sing that daggone song no more until you record it.’”

As usual, Jones’ instincts were correct. Flack recorded the song on Nov. 17, 1972 at Atlantic Studios in New York. Flack arranged the track, Joel Dorn produced it and Gene Paul engineered. Flack also played piano on the track, while Hathaway contributed harmony vocals. The other musicians were Eric Gale (guitars), Ron Carter (bass), Grady Tate (drums); and Ralph MacDonald (congas, percussion, tambourine).

Flack completely transformed the song. Lieberman’s version of the song, produced by Gimbel and Fox and arranged and conducted by Fox, is pretty, but rather bland. Her version plays like a very good demo, which is essentially what it was.

Flack boldly restructured the song. Her recording has a cold open on the chorus “Strummin’ my pain…” Lieberman’s version opens with a long, moody piano solo (which sounds like it could have been featured in Love Story, one of the biggest movies of the era). Then she sings the first verse, only hitting the “Strummin’ my pain” chorus at the 0:51 mark.

Flack also transformed the song from a pop/folk tune to one that drew from a wide range of American music forms – pop, soul and jazz. A 25-second section, which doesn’t appear at all in the Lieberman version, borrows from the scatting tradition. Lieberman’s version ends with a 40-second instrumental outro. In Flack’s version, she is singing until the final note. And Flack sings the song with more passion, bringing out all the drama of the key line, “I felt he found my letters/ and Read Each One Out Loud!”

Flack’s transformation of this song was as complete as Aretha Franklin’s reinvention of Otis Redding’s “Respect” or Ike & Tina Turner’s re-imagining of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Proud Mary.” All three remakes show the power of interpretation – just as Lieberman’s largely unsung involvement in the song’s creation shows the importance of inspiration.

“Killing Me Softly” runs 4:46, longer than any other No. 1 hit on the Hot 100 in 1973. But it doesn’t seem long or padded as it seamlessly moves from section to section.

Fox has suggested that Flack’s version was more successful than Lieberman’s because Flack’s “version was faster and she gave it a strong backbeat that wasn’t in the original.” According to Flack: “My classical background made it possible for me to try a number of things with [the song’s arrangement]. I changed parts of the chord structure and chose to end on a major chord. [The song] wasn’t written that way.”

Flack’s version was released as a single on Jan. 22, 1973, with a version of Bob Dylan’s “Just Like a Woman” (drawn from her 1970 album Chapter Two) on the B-side.

It was the top new entry on the Hot 100 (at No. 54) on the chart dated Jan. 27. It reached No. 1 on Feb. 24, displacing Elton John’s first Hot 100 No. 1, “Crocodile Rock.” “Killing Me Softly” reached the top spot in just five weeks, the fastest climb since Sly & the Family Stone’s “Family Affair” also reached No. 1 in its fifth week in December 1971. “Killing Me Softly” held tight in the top spot for four weeks before being bumped to No. 2 by The O’Jays’ exuberant “Love Train.”

But “Killing Me Softly” wasn’t done yet. It returned to the top spot for a fifth and final week before being dislodged for a second time by Vicki Lawrence’s “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia.” Flack’s five-week run at No. 1 was the longest by any single in 1973.

Flack was a perfectionist, which came into play here in at least two ways. Flack rehearsed the song with her band in the Tuff Gong Studios in Kingston, Jamaica, but she wasn’t satisfied with the background vocals on the various mixes. An executive at Flack’s label, Atlantic Records, assured her it would be a hit song no matter which mix was released. She refused to be rushed, recalling later that she “wanted to be satisfied with that record more than anything else.”

Also, Flack didn’t release an album with “Killing Me Softly” until Aug. 1, 1973, more than six months after the single’s release. That delay must have been agonizing for Atlantic executives. The album, with the shortened title Killing Me Softly, reached No. 3 on the Billboard 200 in September 1973. It would almost certainly have been a No. 1 album if it had been released while the single was being played every hour on the hour on every pop, soul and adult contemporary radio station in the land.

Flack followed “Killing Me Softly With His Song” with a slow and somber Janis Ian ballad, “Jesse.” It stalled at No. 30 on the Hot 100.

At the Grammy Awards on March 2, 1974, Flack became the first artist to win record of the year two years running, after taking home the award in 1973 for “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.” When Diana Ross announced her as the 1974 winner, a dazed Flack put her hand over her mouth. When she spoke, she simply said, “I’d like to thank the world.” (Since 1974, just two other artists have won back-to-back Grammys for record of the year: U2 triumphed in 2001-02 with “Beautiful Day” and “Walk On,” while Billie Eilish scored in 2020-21 with “Bad Guy” and “Everything I Wanted.”)

Flack won a second Grammy for “Killing Me Softly” – best pop vocal performance, female. (She probably should have won a third, best arrangement accompanying vocalists, but she wasn’t even nominated for that one.) The recording was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999.

Killing Me Softly was also nominated for album of the year (losing to Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions). It marked the first time in Grammy history that Black lead artists won album of the year and record of the year in the same year. Gimbel and Fox won song of the year for writing the song.

Flack re-recorded the song with Peabo Bryson on their 1980 double live album Live & More (its title borrowed from Donna Summer’s 1978 collection).

Many other artists have recorded the song over the years, including Johnny Mathis, on his 1973 album Killing Me Softly With Her Song; Al B. Sure!, on his 1988 album In Effect Mode; and Luther Vandross, on his hit 1994 collection Songs.

Fugees recorded an updated, but still faithful and deeply respectful version of “Killing Me Softly” (they shortened the title) on their second album, The Score, in 1996. Group member Pras made the suggestion to cover the song, which showcased Lauryn Hill on lead vocals.

The song reached No. 1 on both the Pop Airplay and R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay charts and No. 2 on Radio Songs. It likely would have been one of the year’s biggest Hot 100 hits were it not for rules at the time disqualifying songs not given an official single release. The track won a Grammy for best R&B vocal performance by a duo/group and an MTV Video Music Award for best R&B video. Flack and Fugees teamed to perform the song on the MTV Movie Awards on June 8, 1996.

Flack’s original track was remixed in 1996 by Jonathan Peters, with Flack adding some new vocal flourishes; this version topped the Hot Dance Club Play chart in September 1996.

Flack returned to the No. 1 spot on the Hot 100 for a third and final time in 1974 with the silky “Feel Like Makin’ Love.” But let’s save that story for the next Forever No. 1 installment.

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor the late Roberta Flack by looking at the first of her three Hot 100-toppers: Her singularly exquisite and rapturous reading of the folk ballad “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.”

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

“When you express your feelings about the first time you ever see a great love, you don’t rush the story,” the legendary Roberta Flack told Songwriter Universe in 2020 — a sentiment applicable to her breakthrough rendition of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” in multiple ways.

Trending on Billboard

One is that the song certainly took its time catching on commercially. Flack, who died on Monday (Feb. 24) at age 88, had shown prodigious musical talent as a vocalist and pianist from an early age, becoming one of the youngest Howard University students ever when she was accepted to the HBCU at age 15. By the late 1960s, she was already both a music teacher and a live performer of some renown, setting up residence as the in-house singer at the D.C. restaurant and jazz club Mr. Henry’s — where she was discovered by American jazz great Les McCann, who immediately hooked her up with Atlantic Records. An album was quickly recorded and released: 1969’s First Take, an eclectic and inspired debut whose centerpiece was its soulful rendering of the ’50s folk song “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.”

Initially, the song went nowhere. It was not even released as a single originally, with the label instead opting to release a split of her funky version of McCann’s jazz standard “Compared to What” and a more meditative cover of singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen’s ballad “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye.” But that single also caught little mainstream attention, and the critically well-received First Take debuted at an underwhelming No. 195 on the Billboard 200 dated Jan. 31, 1970, held at that position for a second week, then dropped off the chart altogether. Flack’s next two albums, 1970’s Chapter Two and 1971’s Quiet Fire, would fare better, both reaching the top 40 — and by the latter’s release, Flack had also found Hot 100 success as a partner with Atlantic labelmate Donny Hathaway, with their duet on the Carole King-penned “You’ve Got a Friend” peaking at No. 29 on the chart in August ’71, just two weeks after James Taylor’s version topped the ranking.

But it was “The First Time” that would, belatedly, mark Flack’s true commercial breakthrough. In October 1971, the recording was featured — in full — during a love montage from the movie Play Misty for Me, Clint Eastwood’s proto-erotic thriller directorial debut. The film was only a modest hit, but its use of “First Time” made for arguably its most striking moment: Two-thirds of the way through the movie, which predominantly focuses on Eastwood’s radio DJ character David seducing and then being stalked by overzealous fan Evelyn (Jessica Walter), the movie takes a long break from the mounting tension to feature David rekindling his romance with on-and-off girlfriend Tobie (Donna Mills). The sequence, of long walks on the beach and through the woods, of making love by the fire and in the grass and even of skinny dipping in the brook, could easily have been mawkish and eye-rolling — but soundtracked by the spellbinding “Face,” it instead served as the film’s emotional climax, and increased public demand for the song to the point where it was finally released as a single, three calendar years after first appearing on First Take.

The other way that Flack certainly didn’t rush the story of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” was in her version’s peculiar arrangement, and its decidedly nontraditional vocal interpretation. Dozens of “First Time”s had already been released by the time of Flack’s spin — dating back to when British songwriter Ewan MacColl first penned the song for Peggy Seeger (half-sister of Pete) to sing back in 1957 — but most of them ran somewhere in the two-to-three-minute range, moving briskly from one verse to the next. Flack slowed the song’s tempo to a candlelit crawl, let the bookending instrumental section stretch out at both ends, and sunk her teeth so deep into the vocal that she turned it from a love song into something more closely resembling a choral hymn.

By the time she was done with it, the album version ran nearly five-and-a-half minutes; producer Joel Dorn asked in vain for her to quicken and tighten it up, saying there was no way the song would become a hit in its current state. “Of course he was right,” Flack would later comment, “until Clint got it.” Still, when Eastwood first reached out to Flack to use her song, she assumed she would need to re-record a peppier version to make it more soundtrack-ready — this was still the era of Paul Newman and Katharine Ross frolicking on a bicycle to “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head.” Eastwood, a jazz aficionado and part-time musician himself, instead assured her that he wanted the song exactly as it was.

In truth, once you hear Roberta Flack’s take on “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” it’s close to impossible to imagine it any other way. Upon entering the song with the title phrase — nearly 40 seconds in, after the fire is lit by some gentle acoustic strumming and atmospheric cymbal brushing — Flack immediately makes the song her own. While most previous renditions had essentially combined “First Time” into a quick “firstime,” Flack takes great pains to enunciate each “t” — “The firsT… Time….” — and then lingers on each word of “…ever I saw your face…” about a half-beat longer than you’d expect, letting the phrase spill all over the measure, in a way that no doubt infuriated those who’d later transcribe it to sheet music.

Flack’s voice at first is mighty but restrained. By the end of the second line, however — “I thought the sun roooose in yoouuuurrrr eyyyyyyyyyyeeeeeees” — she’s in full flight, with a soaring, piercing delivery that fully catches the epiphany of the moment. But by the third line, “And the moon and the stars were the gifts you gave,” she’s already pulling back a little in the smiling afterglow — and by the final line, “To the dark and endless skies… my love…” it’s back to an intimate near-hush. It’s a whole emotional journey and narrative arc in the course of of one compact verse — well, compact in the number of words, though Flack’s vocal contortions stretch the four lines (with one repetition) out to a minute-21 run time.

And so “The First Time” goes for its five-plus minutes. It’s not hard to understand Dorn’s instinctive commercial hesitation with the recording: Not only is it molasses-slow and Led Zeppelin-long, but the structuring of “First Time” is absurdly unconventional for a pop song. It’s just three nearly identical verses and no chorus, with minimal band backing, and only two total mentions of the full title phrase — one at the beginning and one at the end. There’s no particular hook or refrain to speak of, either vocally or instrumentally, and no attention-grabbing shifts in dynamics, no swelling orchestral climax or show-stopping closing vocal runs. Anchored by anything less than one of the great vocal performances in all of 20th century popular music, “First Time” should have been a complete nonstarter on the charts.

But, well, guess what. Flack renders “First Time” with a painter’s detail and a preacher’s passion, a vocal of absolutely disarming clarity and unnervingly visceral feeling. Her vocal elevates the song far beyond even its folk roots to something far more traditional, a canticle, a spiritual. (Flack has referred to the song as “second only to ‘Amazing Grace’” in its perfection.) The song reflects the ecstasy and fulfillment of romantic and sexual union no problem, but also feels like it has its sights set on capturing something even deeper, more elemental — despite the song’s obvious references to physical love (“the first time ever I kissed your mouth,” “the first time ever I lay with you”), Flack said she connected with the song due to its universality, feeling it could just as easily be about “the love of a mother for a child, for example.” Her later-revealed claim that her performance on the record was most directly inspired by her love for her recently deceased pet cat feels so unexpected that it almost has to be true.

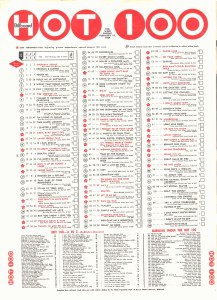

Billboard Hot 100

Billboard

It’s not surprising that Flack’s “First Time” would absolutely knock viewers sideways when showcased — again, in its 5:22 entirety, almost like a mid-movie music video — during such a sentimental stretch of Play Misty for Me. Consumers and radio programmers snapped up the single (with a minute lopped off its runtime, mostly taken from its ends) upon its early 1972 release; the song debuted at No. 77 on the Hot 100 dated March 4, and topped the charts just six weeks later, knocking off America’s three-week No. 1 “A Horse With No Name.” It topped the listing for six weeks total — making for both a rapid rise and a long reign by early-’70s standards — before giving way to another slow song: The Chi-Lites’ “Oh Girl.”

The song would ultimately top the year-end Hot 100 for 1972, and establish Flack as a commercial powerhouse for the era; First Take even re-entered the Billboard 200 shortly after and topped the listing itself for five weeks. It ended up being perfect prelude for the April ’72 release of Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway, her first full LP alongside Hathaway, which reached No. 3 on the Billboard 200 and spawned the top five hit “Where Is the Love?,” soon a signature song for the duo. Flack’s triumphant 1972 was later commemorated at the 1973 Grammys, where “First Time” took home both record and song of the year, and “Love” also captured best vocal performance by a duo, group or chorus.

Flack would go on to have many more hits — including two further No. 1s across the next two years — and escape what could have been a rather intimidating shadow cast by her breakout smash with impressive ease. But as far as her legacy goes as both a vocalist and a musical interpreter, she may have never topped “The First Time,” simply one of the most transcendent and timeless bondings of singer with song in all of popular music. “I wish more songs I had chosen had moved me the way that one did,” she told The Telegraph in 2015. “I’ve loved every song I’ve recorded, but that one was pretty special.”

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor the late Maurice Williams, who died on Aug. 5 at age 86, by looking at his lone No. 1, the doo-wop classic “Stay,” which he recorded as the frontman of Maurice Williams & the Zodiacs.

Maurice Williams & the Zodiacs meet the most common definition of one-hit wonders, as they had just one top 40 hit on the Billboard Hot 100 – but, boy, what a hit. Their doo-wop classic “Stay” reached No. 1 in November 1960, sandwiched between two other top-tier classics, Ray Charles’ “Georgia on My Mind” and Elvis Presley’s “Are You Lonesome To-night?.”

Trending on Billboard

Over backing chants of “Stay!” by his fellow group members, Williams carries much of the song and its plea to a girl to stay out longer than she is supposed to. Her Daddy and Mommy won’t mind, Williams argues, not entirely convincingly. Midway, he steps back and hands the lead to Henry Gaston for one of pop music’s most unforgettable falsetto shouts — “Oh, won’t you stay, just a little bit longer!”

Williams wrote the song in 1953 when he was just 15. The song was inspired by his crush on one Mary Shropshire. “[Mary] was the one I was trying to get to stay a little longer,” Williams told the North Carolina publication Our State in 2012. “Of course, she couldn’t.” (The more restrictive mores of the 1940s and 1950s inspired such other great pop songs as the Oscar-winning “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” and The Everly Brothers’ “Wake Up Little Susie.”)

“It took me about 30 minutes to write ‘Stay,’ then I threw it away,” Williams told ClassicsBands.com. “We were looking for songs to record as Maurice Williams & The Zodiacs. I was over at my girlfriend’s house playing the tape of songs I had written, when her little sister said, ‘Please do the song with the high voice in it.’ I knew she meant ‘Stay.’ She was about 12 years old and I said to myself, ‘She’s the age of record buying,’ and the rest is history. I thank God for her.”

The Zodiacs’ producer, Phil Gernhard, took the demo, along with some others, to New York City and played them for all the label reps that he knew. Al Silver of Herald Records was interested, but insisted that the song be re-recorded as the recording levels were too low. He also said that one line, “Let’s have another smoke,” would have to be removed for the song to be played on commercial radio.

[embedded content]

The track runs just 1:38. It is the shortest of the 1,174 singles that have reached No. 1 on the Hot 100. You could play the song in its entirety six times in the time it would take to play the longest-running No. 1 hit, Taylor Swift’s “All Too Well (Taylor’s Version)” (which runs 10:13, per the dominant version the week the song topped the Hot 100 in 2021) just once. But despite its historic brevity, the record never feels that short. It’s simply exactly as long as it needed to be to tell its story. It’s to the group’s and Gernhard’s credit that they didn’t pad it just to make it longer.

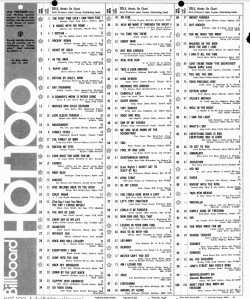

The song entered the Hot 100 at No. 86 on Oct. 3, 1960 – though in a gaffe, Williams was credited as a solo artist. The billing was changed to Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs in Week 2, when the record vaulted to No. 40. The record hit the top 10 on Nov. 7 (when another great R&B record, The Drifters’ “Save the Last Dance for Me,” was No. 1). Two weeks later, it reached No. 1.

“Stay” was only the third No. 1 in Hot 100 history (which commenced in August 1958) that was both written and recorded by a Black artist. It followed Lloyd Price’s “Stagger Lee” (which he co-wrote with Harold Logan) and Dave “Baby” Cortez’s instrumental smash “The Happy Organ” (which he co-wrote with Ken Wood).

Williams and the Zodiacs’ recording of “Stay” was the first major hit for producer Gernhard, who returned to the top five on the Hot 100 in the ’60s and ’70s as the producer of The Royal Guardmen’s novelty hit “Snoopy vs. the Red Baron,” Dion’s poignant “Abraham, Martin and John,” Lobo’s “Me and You and a Dog Named Boo” and “I’d Love You to Want Me,” Jim Stafford’s “Spiders and Snakes” and The Bellamy Brothers’ “Let Your Love Flow,” the latter, Gernhard’s second No. 1 on the Hot 100.

The Billboard Hot 100 Chart for the week ending on November 27, 1960.

Williams and the Zodiacs had two more Hot 100 hits in 1961, but both were minor – “I Remember” (No. 86) and “Come Along” (No. 83). The group had broken through near the tail-end of doo-wop’s peak. Few doo-wop artists outside of the 4 Seasons, which had doo-wop roots, had extensive pop careers as Motown and, starting in 1964, the British invasion took over. A 1965 Williams song, “May I,” seemed promising, but the group’s label, Vee-Jay, went bankrupt just as the song was coming out. “May I” would become a top 40 hit in March 1969 for a white pop group, Bill Deal & the Rhondels.

Williams had had that same frustrating experience, on a much bigger scale, in 1957, when his group The Gladiolas released the original version of “Little Darlin’” (which Williams also wrote). The Gladiolas’ version reached No. 11 on R&B Best-Sellers in Stores and No. 41 on the Billboard Top 100, a forerunner to the Hot 100. But as was common in that era, a cover version by a white group, The Diamonds, became the bigger hit. The Diamonds’ version logged eight weeks at No. 2 on Best Sellers in Stores, and appeared in the 1973 film American Graffiti – a nostalgic film which was perfectly timed as the Watergate scandal broke wide open. American Graffiti received an Oscar nod for best picture and was inducted into the National Film Registry in 1995. The double-disk soundtrack album, a first-rate oldies collection, reached the top 10 on the Billboard 200 in February 1974.

[embedded content]

“Stay” was memorably featured in two films – American Hot Wax, a 1978 film about legendary DJ Alan Freed, and the 1987 blockbuster Dirty Dancing, another nostalgic film that provided relief from the woes of that era, including Iran/Contra and AIDS. “Stay” was featured on the Dirty Dancing soundtrack, which topped the Billboard 200 for 18 nonconsecutive weeks.

Many artists have recorded successful cover versions of “Stay.” In November 1963, the song was released by The Hollies, whose bright, effervescent version shifted the focus from doo-wop to rock’n’roll. Their version reached No. 8 on the Official UK Singles Chart, becoming their first of 18 top 10 hits in their home country.

Two cover versions have reached the top 20 on the Hot 100 – one by the 4 Seasons in April 1964 (with Frankie Valli taking on Gaston’s falsetto part) and another by Jackson Browne in August 1978 (with David Lindley handling the falsetto vocals). Browne cleverly recast the song from a romantic plea to a performers’ plea to the audience to let them play a little longer. Instead of saying Mommy and Daddy won’t mind, he argues that the promoter, union and roadies won’t mind (again, not entirely convincingly!). Browne’s version directly followed his own song “The Load-Out” on his hit album Running on Empty, a No. 3 album on the Billboard 200 and a Grammy nominee for album of the year. That two-song coupling, which also featured vocalist Rosemary Butler, was recorded live at the Merriweather Post Pavilion in Columbia, Maryland.

[embedded content]

There have been many other notable cover versions of the song. The Dave Clark Five recorded the song for their studio album Glad All Over, which reached No. 3 on the Billboard 200 in May 1964. Andrew Gold recorded a version of “Stay” for his 1976 album What’s Wrong with This Picture?, which also spawned his only top 10 hit on the Hot 100, “Lonely Boy.” Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band teamed with Browne, Butler and Tom Petty to record the song at the No Nukes concert at Madison Square Garden in September 1979. The recording appeared on a triple-disc album which made the top 20 on the Billboard 200 in January 1980.

Maurice Williams didn’t have enough hits to receive major honors. He’s not in the Songwriters Hall of Fame (despite writing two colossal hits). He and the Zodiacs haven’t even been nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But the placement of “Little Darlin’” and “Stay” in such iconic films as American Graffiti and Dirty Dancing helps ensure that those songs will live on forever.

And Williams’ place in the Hot 100 record books seems secure: Even with hit songs getting shorter and shorter in the TikTok era, no one has yet passed Williams for his 98 seconds of pop perfection.

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor the late Crazy Town frontman Shifty Shellshock by looking at their lone No. 1 as a group: the surprisingly nice and sweet rap-rock staple “Butterfly.”

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

By 2001, rap-rock and nu-metal had long since taken over the world. From the mid-’90s peak of Rage Against the Machine and instruments-era Beastie Boys through the late-’90s takeover of KoRn and Limp Bizkit and the eventually diamond-certified breakthrough of Linkin Park’s 2000 debut LP Hybrid Theory, bands mixing loud guitars with aggressive rhymes and copious record-scratching grew into a truly massive piece of the music industry. They infected TRL and dominated Woodstock ’99 and terrified your Backstreet-and-Britney-worshipping younger siblings. But they didn’t get to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 until Crazy Town.

Trending on Billboard

To some extent, that’s not surprising. The dawn-to-dusk of the entire nu-metal era transpired when radio was still king on the charts, and top 40 airplay in particular formed the shape of the Hot 100. Many of the genre’s biggest bands were heavy and abrasive enough that they struggled to even secure regular alternative rock airplay, let along crossover playlisting on the pop stations. These groups often outsold the pop hitmakers at the top of the Hot 100, but they weren’t a particularly imposing threat to their supremacy on the airwaves. That was particularly true because, unlike in the hair metal era of the late ’80s and early ’90s — the prior period where hard rock played an obviously central role in music’s mainstream — few, if any of these bands made room for power ballads or love songs between their ragers, the kind of songs that could expand both their radio reach and their demographic appeal. In other (highly reductive) words, none of these bands of angry young dudes wrote songs for women.

[embedded content]

Crazy Town did, though. Or at least, they wrote one, for one woman: “Butterfly,” co-penned by group frontman Seth Binzer — known professionally as Shifty Shellshock, who died this week at age 49 — was inspired by a new girlfriend who made him take a second look at his traditionally misogynistic lyrical content. “I was in love [with her,] and she was asking, ‘What’s up with all these lyrics? Is that what you’re like?’” Shellshock recalled to Fred Bronson in The Billboard Book of Number One Hits. “So that made me come up with the concept of writing a song to her. Instead of writing a male chauvinistic song, I was going to write something nice and sweet to a girl I cared about.”

The lyrics to “Butterfly” are indeed nice and sweet — particularly compared to distinctly un-Hallmark prior Crazy Town singles like “Toxic” (“F–k the critics, we leave them hanging like INXS”) and “Darkside” (“Unearthin’ untamed perversion/ My bad brain’s workin’, circle-jerkin’”). Rather, “Butterfly” celebrates the titular love interest with a series of straightforwardly romantic and decently heartfelt verse tributes (“I used to think that happy endings were only in the books I read/ But you made me feel alive when I was almost dead”) and a chorus hook (“You’re my butterfly, sugar baby”) worthy of The Archies. A few questionable couplets, namely one from co-lead Brett “Epic” Mazur comparing him and his intended to storied punk lovers Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen — who died by murder-suicide at the former’s hand — invariably opened the song up to Awesomely Bad-type ribbing. But as far as 21st century mainstream rock love songs go, it’s actually pretty touching.

More critical than the lyrics, though, was that the song sounded especially nice and sweet. Whereas the overwhelming majority of signature nu-metal anthems were confrontational head-bangers, the beat to “Butterfly” is a slow-and-low shuffle, with the record-scratching mostly contained to a background flourish. And while no one would mistake Shellshock’s rapped lead for one of 98 Degrees, his come-ons wisely hew closer to gentle invitation than yawped insistence; the most striking vocals on the entire song come via the complementary toneless backing whispers on the hook (“You make me go CRAZY….“)

[embedded content]

But what really gives “Butterfly” its wings is the Red Hot Chili Peppers sample. In fact, in terms of both inspiration and utility, you could make the case for it being one of the 10 most important pop samples of the entire 21st century — it’s hard to think of too many other hits this big where the lift was this crucial to both the makeup of the song and the reason for it taking flight. Especially because its source is at once both incredibly obvious (a mostly shirtless bunch of SoCal rap-rockers finding kinship with an RHCP track, duh) and remarkably obscure: The percolating bass, weightless guitars and rising-sun horns of “Butterfly” are looped not from one of the Chili Peppers’ hits, but from a pre-crossover 1989 deep cut called “Pretty Little Ditty,” a disorientingly gorgeous four-measure pattern that briefly materializes mid-song and disappears for good immediately after.

While the mini-groove was just a flash of divinity in the original “Ditty,” it makes up the whole musical spine of “Butterfly,” running throughout the entire track. Mazur admitted to Bronson he never expected to get the sample cleared, given the band’s traditional reticence for approving such recycling of their songs, saying, “If we had to fight to get it cleared or they didn’t like it, we would have come up with some other music.” It’s utterly impossible to imagine any version of “Butterfly” without the full “Ditty” sample, though — everything about the song’s particular alchemy depends not only on the sample’s melodies and sonics, but in the built-in (and lived-in) Chili Peppers reference point.

Hot 100

Billboard

However, with the heavenly sample elevating Shellshock’s sealed-with-a-kiss mash note lyrics — and a perfect accompanying visual in the lush, pleasantly psychedelic music video, co-starring his eventual wife Melissa Clark — “Butterfly” flapped higher than even any RHCP hit. While the latter band’s generational power ballad “Under the Bridge” stalled at No. 2 on the Hot 100 (behind Kris Kross’ “Jump”), Crazy Town’s breakout smash got all the way to No. 1 on the chart dated March 24, 2001, replacing Joe’s “Stutter” on top. It then gave way to Shaggy and Rayvon’s “Angel” — another romantic ode based around a lovey-dovey-all-the-time rock lift — before reclaiming the top spot, then ceding it for good to Janet Jackson’s seven-week No. 1 “All for You.”

“Butterfly” was not only Crazy Town’s only visit to the Hot 100’s top spot, it was their sole cameo on the entire chart. Gift of Gab follow-up “Revolving Door” made the Official UK Singles Chart’s top 40, and “Drowning” (from 2002 sophomore LP Darkhorse) earned some rock airplay, but the group was never interested in attempting another “Butterfly,” and they broke up shortly after Darkhorse. Shellshock had better fortunes outside of the group, scoring another sublime summery smash with the Paul Oakenfold-led dance-rock skate-along “Starry-Eyed Surprise,” peaking just outside the Hot 100’s top 40 and making the U.K.’s top 10. He scored one more minor hit with the solo “Slide Along Side” (as just Shifty), but his music career was largely sidelined by substance abuse; when he returned to music television in the late ’00s, it was as a cast member on VH1’s Celebrity Rehab.

[embedded content]