Features

Page: 4

“Interviewing Grace Wales Bonner at the Guggenheim” sounds like a bar you would hear from Westside Gunn, or some other rapper with a high level of fashion sense and sophistication. But that’s what I did over the weekend when I had the pleasure of being invited to the British designer’s latest iteration of her “Togetherness” series where she brings people together from different walks of life that share similar interests when it comes to style, music, and art.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

There was an exhibit by multi-disciplined artist Rashid Johnson entitled A Poem for Deep Thinkers serving as the event’s backdrop, as sounds from electro-R&B genius KeiyaA and pop fusion maven Amaarae bounced off Johnson’s pieces — which included things like a framed throwback dashiki jersey (signed by “Civil Rights All-Star” Angela Davis), and sculptures made out of shea butter.

Trending on Billboard

Like most of the acts performing, Grace Wales Bonner is multi-faceted, incorporating different reference points into the clothes and accessories she designs for her Wales Bonner fashion house thanks to an almost maniacal obsession with research that then bleeds out into what she presents to the world. When I was walking to the event from the 86th St. stop, I noticed Nigerian rock band Etran de L’Aïr smoking cigarettes outside as they relaxed before they tore the house down later that night — but the first thing I noticed was that they were wearing brown traditional thobes while wearing yellow Adidas x Wales Bonner Adios Neftenga on their feet.

That’s Wales Bonner’s approach right there in front of me. The label mixes high fashion with traditional and street fashion. Soccer kits, durags and sneakers aren’t strange things to see on the label’s runway models. It’s that juxtaposition that makes the brand so interesting.

Etran de L’Aïr at Grace Wales Bonner Presents: Togetherness at Guggenheim New York on May 3, 2025.

Hannah Turner Harts/BFA.com

This year’s “Togetherness” event was no different and the melting pot that is New York City was the perfect setting. Hip-hop serves as one of Bonner’s many influences and reference points. “The street photography in New York is a way of understanding sound like looking at what people are wearing around their sound systems,” she said during our quick chat, as she referenced the photography of Jamel Shabazz during the early days of hip-hop. “Music and sounds are part of those references.”

When it came to how she approached curating the wide array of acts, she credited the city’s diversity as inspiration. “I feel like that’s what feels quite special about New York,” she began. “That’s what I always love. You can be with people of lots of different ages together, kind of like multi-generational, while also supporting each other. I think I’ve also been thinking about nomadic sound culture and people moving around and taking different influences through that movement. So, that’s been an influence in terms of programming — movement throughout the space and unexpected moments of discovery.”

One of the acts that incapsulated the event’s thesis statement was model, skateboarder and rapper Sage Elsesser, who goes by the artist name Navy Blue. Dipped in Wales Bonner from head-to-toe, he performed songs in the museum’s Lewis Theater and spoke to me about the similarities between his form of storytelling with Grace’s. “Music is the way that I express myself the best,” he told me in a quiet corner tucked away outside of the theater. “It’s the place where I get to express all of my interests and life experiences, like how I was raised, the food, it’s all of it, you know? It’s so multilayered. I think any artform is the crux of where all of your interests meet. So, I get why Grace is so inspired by music, and why she wants to have music be a part of her storytelling.”

Grace says that they first met through the fashion scene in which they both occupy. “There’s different ways that he can show up in the world of what I do,” she said of Elsesser. “I’m a fan of his music, so artists working with artists feels like quite a natural evolution. I’m always kind of like working and collaborating with different artists and researching a lot of different music for my shows, and have relationships with people that have grown and become organic.”

Another one of those artists that Bonner is referring to is Amaarae, whose style of music is hard to put in a box. She and Grace have been trying to connect on something this impactful for a minute and finally got the opportunity to do so. The two of them approach their art in a similarly unpredictable way.

“I think that a great artist is a great artist,” Amaarae told me backstage. “Whether you make music, films, clothing, draw, sculpt, or paint, I think that you go through life, and everything that you do, everything that you go through is a result of your influences and the things that inspire you.”

She added that one can only be inspired and influenced if they live a rich life culturally and educationally. “I absolutely feel the connection to Grace,” she said. “Just the way that we approach art, not just with music and fashion.”

“Togetherness” at the Guggenheim was a special event that bridged the gap not only culturally, but generationally. “I feel like there’s a strong sense of community in New York, which I really love,” Grace said “I also feel like there’s a kind of elevation and kind of sophistication about sounds I hear coming from New York, which I also see in my peers and their music.”

As New York Knicks captain Jalen Brunson would say, the vibes were immaculate on Saturday night (May 3) and I can’t forget to mention the fits which were of course very much splashy, very much flee, very much “I got that s–t on.”

Ryan Coogler’s Sinners – a Southern Gothic vampire-musical-period epic led by Michael B. Jordan – is an irrefutable juggernaut. With thousands of moviegoers clamoring for prized IMAX 70mm tickets and endless discourse across social media, Sinners is perhaps 2025’s first genuine cultural phenomenon – and the haunting Raphael Saadiq-penned “I Lied to You” sits at the center of it all.

Performed by breakout star Miles Caton in a pivotal – and instantly viral — scene tracing the history and legacy of Black music, “I Lied to You” is, at its core, and simple acoustic guitar-and-vocal track that effortlessly conjures the spirit of 1930s Delta blues. Already a leading contender for 2026’s best original song Oscar, “I Lied to You” marks the union of Saadiq, a Grammy-winning R&B maestro and founding member of Tony! Toni! Toné!, and two-time Oscar-winning composer and longtime Coogler and Childish Gambino collaborator Ludwig Göransson. Built around a refrain Saadiq, now 58, first came up with when he was around 19 years old, the song’s journey also mirrors the timelessness of blues songwriting.

Trending on Billboard

Saadiq — who’s no stranger to scoring films, having contributed music to everything from Soul Food and Baby Boy to Empire and Love & Basketball – could pick up his second career Oscar nod for “I Lied to You.” In 2018, he earned a best original song nomination alongside Mary J. Blige and Taura Stinson for Mudbound’s “Might River,” bringing him one step closer to an EGOT. In addition to a 2021 Emmy nod, Saadiq has collected three Grammys, including a recent win for album of the year thanks to his work on Beyoncé’s culture-quaking Cowboy Carter LP, the latest addition to a catalog that champions the breadth and depth of Black music.

“We’re the ones chosen to raise the bar – and the bar has been pretty low in a lot of different areas,” he tells Billboard of artists like himself, Beyoncé and Coogler. “Some choose to not let the bar be that low, and that’s what happened. When somebody calls your name, you go to be ready.”

For an artist and musicologist like Saadiq, all of that hardware pales in comparison to connecting with the fans who have sustained his nearly four-decade career. At the top of the year, he launched an exclusive vinyl club for fans to peruse his legendary vault, access exclusive artwork, and enjoy quarterly releases of old and new work. On May 31, the esteemed multihyphenate will launch his No Bandwidth one-man show at New York’s iconic Apollo Theater, his first totally solo trek.

In a wide-ranging conversation with Billboard, Raphael Saadiq talks working on Sinners and Cowboy Carter, drawing inspiration from Mike Tyson, and where he hears the blues today.

When did Ryan Coogler first approach you to contribute a song to the film?

I think maybe a week before he went to shoot it in New Orleans [in April 2024]. He reached out to me and gave me the full scope of what the movie was about. He told me that his uncle was a blues guy and explained how the church had a problem with blues players. There was a separation. But it wasn’t that the blues players didn’t believe in God, it’s just that the blues was their church.

It was right up my alley because that’s exactly how I grew up. Playing R&B music, I was told that I was playing the devil’s music, too, so it made sense to me.

What was your initial reaction to the plot?

I don’t even know if I really understood the plot completely. There’s really no way to understand it by someone telling you. You need to see it. He gave me some guidelines, and I took it from there. I was used to doing that because I worked with John Singleton a lot on some pieces – he was the one who told me I should score film. John would tell me what was happening in the scene, and that was really good practice because I didn’t really have enough time [to write “I Lied to You”]. The movie wasn’t shot. I didn’t hear [the song] until the movie came out.

What was most unique about the Sinners process?

The passion of the story. I have so many stories of Howlin’ Wolf, O.V. Wright, Bobby “Blue” Bland and B.B. King playing in my house growing up. This process really brought me back to my Baptist church roots. Even the humming that I’m doing on the track – I got that from Union Baptist Church. We call it devotion-type singing.

Without seeing any of the dailies, I knew [that humming] would fit. I didn’t know how well it would fit, but it was really some kind of ancestral-pilgrimage-storm. And [Miles Caton’s] voice… oh my God! That voice is crazy. I never heard his voice, so I just wrote the song how I would sing the blues.

They wanted me to put my demo out as well, but I felt like the movie is so amazing that when people go to DSPs – they should only hear Miles. I love his voice.

Where do you think Sinners fits in the legacy of Black music films?

I would say it could match The Color Purple. I would have said Superfly, but Curtis Mayfield had way too much music in there. But the way Ryan likes to work, one day, I know he’ll make a very musical shoutout to the world, like what Curtis Mayfield did with Superfly. I feel like that’s on the horizon.

Walk me through the session in which you and Ludwig Göransson wrote “I Lied to You.” How did you capture the essence of 30s Delta blues despite using modern tech?

In a modern time where people have a lot of outboard gear and different compressors, it doesn’t matter what you have, it’s really in the fingers. It’s in the hands. It’s in the mind of the person that’s doing it. I was playing an acoustic guitar in Ludwig’s studio, and we jammed for a second. I wrote the lyrics on the spot right there, and recorded everything that night. And then Ludwig scored the hell out of it [for the Black music history montage] – I wasn’t there for that.

What musical touchstones from your career and catalog did you pull from to write this song?

I’ve always had blues ideas, but I never thought I had the voice for blues. I would just sit around and make blues hooks because blues hooks are the best hooks ever. When I was younger and struggling to tell my girlfriend the truth about something, I said, “You know what would make a good blues song? They say the truth hurts, so I lied to you.” I’ve always had that.

I had another one when I was a kid; my mom asked me to do some work, and I remember thinking, “I’m so young, with the way she’s treating me, I might as well grow a beard.” [Laughs]. I never told her that, but I sang it in my room.

For [“I Lied to You”], I thought Sammie’s character was lying to his dad, but he wasn’t really doing that. He was telling him the truth. But [at the time], I thought he was lying, so that’s why I landed on those lines.

What makes a real blues voice?

You hear how Miles talks? He sound like somebody grandpa. He got that thing; he got that it factor. You gotta sound gravelly. I have to try to sing a blues song. He just gotta open up his mouth. My dad would tell me all the time — that I had to change my tone if I was gonna sing the blues. But I’m a tenor dude, I got a pretty voice. I just don’t think that I have a blues voice. I’ve gotten raspier and know how to do it now, but when I was in Tony! Toni! Toné! in the 90s – and it worked, I’m not complaining! — [my voice] was cute. Once I did my The Way I See It album, I learned how to sing and act like David Ruffin. Never had his voice, but I could mimic things. But this kid [Miles] doesn’t mimic nothing! That sound just comes out.

What was it like when you finally saw that key scene?

Honestly, the second time I saw it, I closed my eyes, and I prayed. I saw it for the first time with Ryan in IMAX at the premiere in Oakland. But the second time, I understood the movie even more. I hadn’t been back in Oakland since my brother [D’Wayne Wiggins] passed about two or three weeks [before the premiere]. I had a whole lot in my mind, and I was just very grateful and thankful.

The music from all those time periods – from the ‘30s to Parliament-Funkadelic – is all the things I grew up with. I’m not old enough to have been there with John Lee Hooker, but my father was born in 1929 and he’s from Tyler, Texas. My mother’s from Monroe and Shreveport, Louisiana. The gospel quartets I played in as a child, all those men — they all picked cotton. That was their job. So, I’m not removed; I grew up in a house with people who did that. When the movie opens up? That was probably my father. To be able to contribute music to a piece like that… it just came out.

Did you also feel a link between Remmick’s character and predatory record execs?

Definitely. When he said, “I want your stories…” Wow… We all make music — Black, white, Asian, etc. A lot of people are really good at it; it’s a universal thing. I know some bad players in every genre, singing, drumming, bass guitar, arranging, anything. The gift is not given to just one nationality, it’s given to all.

But the one in Blues, we own it. The soul s—t, we own it. Nobody got us with that one. This is ours. I know this because in my car I’ll listen to everything from classical to classic rock – and I still come back to the soul station or some blues station. I think the world understands that about Black culture and Black music. It’s not like they don’t know. We put spice in the game.

That bluesy storytelling is also present on “16 Carriages” and “Bodyguard,” two Cowboy Carter tracks you worked on. What was that moment like when they called the album’s name for best country album and album of the year?

I’m not big on Grammys or awards, but I was that day! It felt really good. I had a nice glass of champagne and a really good time just being there. Beyoncé works so hard, it’s just crazy; when somebody works that hard, they deserve it all. I really like to work with people who can work harder than me and match my work style – and I work really hard! It’s great to see someone who has accomplished so much already – who you would think Grammys don’t mean that much to, but I’m sure they do – continue to be driven by something that’s definitely not awards. It’s something deeper. I was honored to be a part of it.

I don’t really remember too much about working on the record, because we were just having a good time. The only thing I remember is when I played the guitar solo on “Bodyguard.” I don’t normally do guitar solos; I’d probably just call my boy Eric Gales, who plays guitar all over [Sinners]. We were going to have an eight-bar solo, and Beyoncé was like, “Nah, you can go 16.” We were in a time crunch, and I didn’t have time to call somebody, so I had to go in the room and play the solo, which I could already hear in my head. I loved that challenge. I always love passing work to great people, but this time I had to jump on it. It was fun cutting a Dirty Mind-era Prince guitar solo.

Sinners and Cowboy Carter are two landmark works that, at times, feel in conversation with each other. How does it feel to be able to work on these projects and intertwine your own legacy with theirs?

I love the storytelling on both Cowboy Carter and Sinners. It feels like we’re the chosen ones. I’m just in the right place at the right time. Not to sound cliché, but people can either wait for things to happen, or take the road less traveled and find other people traveling that road who don’t have the platforms to be heard. Like what Bey did on Cowboy Carter, grabbing different artists like Shaboozey. Look at him now. Look at Ryan grabbing Miles and giving him a platform.

There’s a lot of people who don’t have a platform and probably could do it better than we’re doing it. But with these projects, we’re showing that we hear you. We hear that something real has to happen in music and film. We’re the ones chosen to raise the bar – and the bar has been pretty low in a lot of different areas. Some choose to not let the bar be that low, and that’s what happened. When somebody calls your name, you go to be ready.

Your one man show, No Bandwidth, kicks off at the end of May. What are you most looking forward to about taking the stage by yourself?

Looking at Neil Young’s one-man show and watching Mike Tyson’s [show] is what really made me want to do one. When I saw it years ago on HBO, I was like, “Man, Mike did a good job. I wanna do that!”

I feel like I have some stories to share with people about my life, and [I get to play] some of my favorite songs. I’m gonna play a little bit of piano. I’m no Prince on the piano, but in the pandemic, I fell in love with the piano. I might play a couple of tunes I learned during that time. When I was a kid, I took piano, but I quit because I wanted to go play basketball and football with my friends. My teacher told me, “You’re gonna wish you kept playing,” and I knew she was telling the truth, but I was already pretty good on the bass. [Laughs]. But I’ve always written songs on piano, just never retained anything. Now, I’ve bought maybe three or four different pianos, so I took up lessons again.

Why did now feel like the right time to open up the vault and launch your vinyl club?

Some people may have loved some of the music that I put out, and some of their friends may have never heard it. It’s always good to be discovered. If you can be discovered twice, and be discovered on vinyl, that’s even more of a thrill for me. It also puts you in a different creative space of creating artwork, which makes them more of a collector’s item. It kind of feels like when the Grateful Dead had people going to different cities just to get different cassettes with different artwork.

I [also] wanted to create some new vinyl with music I haven’t even made yet. I wanted to start [the vinyl club] off with some things I have in the vault.

Where do you hear the blues today?

I once talked to B.B. King, and I asked him, “You think more Black people should play the blues?” He said, “Let them do what they do, and we do what we do.” I think the energy came from his being okay with his huge fan base playing the blues. But I felt like more people should know about it and play it. It’s a big genre. It’s something you should always have in the vault and listen to.

I think where it is now in the South is more like [Hampton, Va.-born soul/R&B singer] King George’s “Keep on Rollin.” That’s the blues today. Sometimes when you hear different MCs, they also sound a bit bluesy to me. But in terms of blues guitarists, it’s more others doing it than us. That’s just how it goes. But back in the day, that Delta blues was just a whole different life, a second language.

Conductor, we have a problem! Conductor!

If you haven’t heard that saying while listening to rap music, then you need to diversify your listening habits — because Kansas City’s Conductor Williams has quickly become one of the latest underground acts to crossover into the mainstream, as rap music continues to fight for its soul the more it dominates the charts. He’s been at this beatmaking thing since the mid 2000s, when he worked with New York-based rappers like Outasight and Fresh Daily around 2008. However, Williams didn’t really begin to find his groove until he decided to reinvent himself in 2016 after falling on hard times. “It was just a moment where everything changed,” he said. “So, maybe I needed to change too.”

Fast forward a couple years and Griselda Records founder Westside Gunn is in his Instagram DMs asking him to take a video down about a beat he made because he wanted to use it for his upcoming album Pray for Paris which then began his swift ascension into becoming one of the most in-demand producers in the game today. He’s made beats for the likes of Drake, J. Cole, and Joey Bada$$, who have all reached out to him when they feel like they want to rap a certain way and reach a certain audience. And while they haven’t worked together yet directly, Tyler, the Creator helped him win a Grammy when he used one of his beats on his song “Sir Baudelaire.”

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Conductor is now planning on producing full-length projects with guys like Rome Streetz, just as he did with the impressive Boldy James record Across the Tracks and wants to put out more instrumental tapes. We caught up with Williams and talked about a wide array of topics, ranging from how he got his start, his process, and the moment when he started to climb out of the shadows of the underground, among other things.

Trending on Billboard

Check out our talk below.

You smoke a lot of cigars. What’s your favorite brand?

This is a Joya de [Nicaragu.] This is a classic joint. I suppose the story goes that President Nixon made these the office favorite during this term, or something like that. But this is just a staple, and more than anything, it’s just a moment for me to stay still. If not, I’d be trying to do all kind of s–t but once I light one up, I got 40 minutes. So, it’s kind of meditative and enjoyable in that way.

What were you doing before you started producing, like as a day job?

I worked for a railway and my father did it too, and my uncle. I did that, but I went to university too, and I got out of university and then got a job with the old man doing that.

Were you alway interested in production?

Yeah, I was making beats in college and just fascinated with the process in college. Before college, I just loved music, you know, I’m saying playing little shows and colleges and stuff like that, house parties. But the love for actually making the instrumentals day come until maybe my last year of college was when I was like I’m gonna start cooking and see how good I can get. And I did that locally. And I did it to a place where I kind of like, I wouldn’t say I had outgrown Kansas City hip-hop, but I got to a place where I kind of worked with everyone, and it was kind of boring, and I was like, working a full time job, so I decided to attack the Internet. And that was actually the best gift, was me deciding to use the internet and meet other people around the world.

I started with the beats in like 2008. There’s a cat from out here — his name was Outasight at the time — and him and I linked on Myspace. Around 2008 is when I felt like I was good enough to start sharing music with people outside of my city and then by 2016 is when I decided to stop working with everybody and only focus on myself. I wanted that instant gratification of making a beat and seeing what everybody says about it, so I started posting instrumentals on Instagram. So, selfishly I wanted to know how good and entertaining my beats can be without having a rapper on them. Then I learned Adobe Premiere, and just kind of started hustling on how to present myself differently.

In your Amoeba record store “What’s in My Bag” video you had a J Dilla Donuts vinyl, and mentioned how much it influenced your production style. Were you listening to a lot of Dilla, Madlib, and DOOM beat tapes at the time?

Yeah, a lot of that. Pete Rock, too. And I honestly think Dilla was about to take it to a place where it was about to turn into jazz records, like instrumental beat tapes were about to be jazz records. He just didn’t get a chance to finish his ideas. But I think the idea that he started is like, “Yo, beats and samples can be told into stories in that way.”

You mentioned that you decided to reinvent yourself around 2016 and a couple years later you pop up on some Griselda records. Talk about that relationship a bit.

Ironically, the thing about Griselda that I haven’t been able to articulate yet because I haven’t had a chance to is that they were just outsiders. West and those guys kind of viewed themselves as outsiders, coming from Buffalo, and I was in Kansas City feeling the same way. And, you know, through the stars and through God, we all kind of met, so I didn’t never have to change my s—t. They really appreciated that. Westside Gunn really appreciated me being me. It just so happened that we were in the same mindframe.

How did you guys link up?

Instagram.

Did you hit him up?

The blessing of my career has been that everybody hit me directly — like, there hasn’t been a time where someone tried to go through a manager or an A&R yet. We’re getting to that place now, but all of the records that you’ve heard, they DM’d me. So, there’s something interesting about isolation and a one track mind, a one track system that I created where it’s like, “Yo, you got to go to that guy to get that thing.” And if you don’t go to that guy and get it, then you won’t get it. That’s kind of been the allure of things, you know I’m saying?

But West just seen me post a video the of the “Euro Step” beat I did, which was the first record he chose on Pray for Paris. I posted the beat video of me making it with cartoon projections behind me, and he hit me on a DM and was like, “Yo, take that down. Take that down. I need that. I need that send that.” And he was in Paris with Virgil, and I want to say Mike Dean. It was a bunch of people that were there. That’s kind of how that all started.

You’re very proficient with your vlogs.

That was the thing. I would make beats all week and then on the weekends I would work on videos for the next week.

So, you already had a strategy.

I don’t know if you have children, but when you have that responsibility and your dream or your passion is for real, you gotta figure it out. It’s not a matter of like, “I can’t make beats this weekend.” That was never the case, it was always, “How am I going to make beats this weekend?” You gotta figure it out. More than anything, persistence was the key there.

Your vlogging got you in a little bit of trouble, or that’s the rumor. You posted the Drake “Fighting Irish” freestyle and had to take it down.

That’s my brother. It was never “trouble.” It’s wasn’t a situation of like, “Yo, why the f—k you do that? Take it down right now.” It was just like, “Yo, Conductor. I know we were gonna do that, but not right now.” It was all good and it wasn’t a big deal. And eventually we’ll get to that. It was just like a miscommunication on both sides. And it’s like, “Yo, Conductor, can you take that down?” And it’s like, “Yeah, sure, I can take that down.”

You’re giving people advice on your vlogs. Some of them almost feels like a diary.

It is like a diary to a certain degree, but with the YouTube specifically. I wanted it to be what I wanted from somebody else, like what I wanted from the RZA or some other god-tier producer. Like, what would the villain do? What would DOOM do?

And you mentioned that he’s your favorite rapper.

I would say DOOM, West, and Evidence are my favorites. My top MCs are super strange for my taste.

What is it about Gunn’s style that you like?

It’s the character that he is. It’s how the music makes you feel. It’s his confidence. The way he loves himself is how we should all love ourselves. And a lot of us feel that way, but we don’t got the guts to say it. So, when you listen to a Westside Gunn record and he’s saying, “I’m the flyest ever,” and you’re rapping that, then it’s like that loop of you saying that out loud, you know? I tell West all the time, “You can rap, bro.” I think he is as nice as the other two. For the life of him, he’ll be like, “Nah, I don’t even rap. I’m a fashion n—a.”

Your beats reminded me of Dilla, DOOM and Madlib when I first heard them. You’re from that school of thought. The loops, the cartoon sounds.

Ultimately, those guys inspire me a lot. More than anything, bro, it’s just trying to find a way to tell a story through the instrumental, more than emulating the style, and a lot of it is necessity too. I don’t like computers like that. I don’t like synthetic sounding music. But the studies, though, the studies is all Dilla, you know, and I don’t know how I got spit out in the universe of like DOOM and Madlib, but the studies are completely all Dilla.

I think the results of the studies is something like “8am in Charlotte.” That record is all of the years of studying the legend and trying to not be like him. There’s times where I’m cutting a sample and I gotta turn the machine off, because it’s going Dilla World — because I’ve studied it so much.

You’ve said that you used to make five-to-10 beats a day. Has that process changed now?

I’ll never master the machines, but I’m at a place where I know how to get what I want. Now that I’ve got there, it’s about why am I doing what I’m doing and if it’s making sense. The part of the process that hasn’t changed is once it’s in the machine and to tape? I’m not an edit guy. I’m not listening to it constantly and going back to change the kicks. That s—t is cooked.

I don’t know if you ran into this, but I feel like at least for major label releases, even someone like Drake, right? Maybe you’ll come with something to the table, and then like, Boi-1da or somebody else will come, and they’ll add there bells and whistles to it.

The gift of this whole s— is a gentleman in Missouri making the records that he makes with the feeling that he gets. They want that. When they come to me, they’re like do whatever you do. On the Cole record “7 Minute Drill” there’s a baseline in there, it’s like a sine wave base, or an 808 — maybe elongated one — and Cole was so kind and almost halfway anxious about asking me if he can add it. He hit me a couple times that day that he was gonna add that little bass in there, and it was needed.

I want the best piece of art imaginable for the fan when they hear the track. It’s death of ego at all times, unless you’re trying to change my whole s–t. If you want to come in and pitch up the sample and put extra drums, then it’s not what I do. So maybe you should try, you know, by yourself, but it’s death of ego every time I touch down. And that’s the source of what I create out of and I think a lot of artists get that about me, and that’s what they respect most.

How did you feel about the drama surrounding that song? The Alchemist talked about “Meet the Grahams” and he said that he can’t control what rappers say on his beats.

And Al told me the same thing. You can’t control it. My job is to service the artist as best as I can. For me, being a man controlled by God, things that are blasphemous always alert me. Like n—as on some devil worshiping type s–t. You know what I’m saying? “God ain’t real, n—as out there praying is suckas.” I’m like, “Yo, chill out” [Laughs.] I’m one of those, one of those people. Other than that, it’s entertainment, and the artists that work with me come to me for the art.

So, you didn’t feel a way that he decided to delete it.

No, because he communicated.

So, Joey Bada$$, J. Cole and Drake all reached out to you?

Everybody reached out. You know what’s funny? There are fans that say I don’t do any music with the West Coast, but that music is coming, bro. The records with the Jay Worthys and the Larry Junes and the Ab-Souls are coming. N—as are reaching out, you just gotta wait.

You know what it is, too? I think it’s the stan stuff on social media. You made a beat for Drake, so you’re not allowed to make a beat for Kendrick.

You know what I’m saying? Why not? That’s that weirdo s–t. It doesn’t make any sense. I’m doing my job. At the end of the day, it’s rap at its highest level, and I’m just thankful to be a part of being of any of it.

What’s the difference in approach when you’re working with different rappers? What’s your process like?

This is pretty important because it’s maybe ethos at this point, no matter who the artist is — and Drake kind of ruined it for everybody in the best way — because a man of his stature and his schedule and his life still had the time to communicate with me about what he was feeling, what type of records he was listening to, where he was at with the pen, and that’s the beginning of the process with everybody.

Rarely is it getting a beat off the shelf. Generally, they pick off the beat tape and then we’re having more conversations about what’s happening. This is nothing more than a movie director or a movie producer. N—as don’t just show up to Tarantino and they want him to do a movie for them and they don’t talk about it.

So, the beat that they pick off the tape initially isn’t necessarily the one that they rap over?

With Drake, Joey and Cole, they pick off the beat tape and then they reference other songs in history, whether that be hip-hop or jazz. So, now I’m creating in their world. It’s a commutative thing, and that’s why them records feel like that. That’s why I can’t make another “8am” for Joey, because of the conversation and the energy that went into me building with Drake in that room.

So, you prefer a very collaborative process instead just handling things over email?

I want to know what the artist is thinking. A lot of folks be like, “Yo, I came to you because I’m trying to rap.”

You’ve become the go-to guy for the mainstream cats when they wanna get on some real rap sh—.

Yup. They be like, “I got some s–t I’m trying to talk about. I’m trying to get people to feel that I’m in a place,” and then they come to me.

Conductor Williams

AMES CREATIVE

Can you elaborate a little bit more on how different your relationship is with Gunn compared to other people?

I feel like if something terrible happened to me, Gunn would provide for my family. I’ll never be broke and I’ll never be down bad. He’ll pay for my kids to go to college if I’m not able to. That’s the difference between my relationship with him and everybody else.

I wanted to get into when you decided to rebrand yourself. Were you frustrated when you decided to do that?

It was a moment of internal reform. My granny had died. I went through a bad relationship. I was living in my car a little bit and couch hopping. I really didn’t have no money like that. I got laid off at the job. It was just a moment where everything changed, so maybe I needed to change too. And then there’s a record that I just re-released that I put out in 2018 called Listen to Your Body, Talk to Plants, Ignore People. I started building beats for that in 2016 because I changed my life.

I started like this hybrid vegan thing which was probably more vegetarian looking back at it. I really started my journey in mindfulness and meditation, and actually took it serious. I cut off all my friends, and the ones that were truly friends are still here with me now, but I cut off everybody. I didn’t resort to s–t like gambling, manipulating women. I didn’t start drinking and smoking weed or getting into drugs. I just stopped everything and I started finding what I truly was as an artist. I thought about not doing this anymore and going back to the railroad to make a career out of it. I was at a crossroads and I let God direct me.

What was your big break?

There’s a couple. I met Remy Banks.

Remy is a friend of the family.

Remy introduced me to Evidence who was going through something personal at the time. He wasn’t in the headspace to rap. He didn’t want to do anything, but he saw my output and linked me with Termanology. So, Term was the first person to put his brand with mine and I did a couple joints on his album Vintage Horns around 2019.

Shortly after that, Westside Gunn reached out for Pray for Paris and we did “Euro Step.” Then came “Michael Irvin” where he rapped, “You ever cook a brick in an air fryer?” And that worked so much, Tyler, the Creator used it. Also, Mach-Hommy’s Pray for Haiti was a really big moment because he put my three records back-to-back-to-back. Those are the type of things that visionaries do and I honestly feel like West saw what I was building towards and put me in position to execute.

Have you and Tyler talked about working together? Because you guys remind me of each other. You both have a natural curiosity, a willingness to learn, and an appreciation of history.

Nah, man. I feel like it’ll be soon, though — because I’ve been working with Domo [Genesis.] We got a lot of incredible things in common, you know, even down to our days of birth. His birthday is on March 6 and mine is on March 5. I also hear from a lot of people there we’re a lot alike, so I’m just curious to see if that’s true or not.

Let’s talk about the tag. How did that come about?

The idea is going back to the 2016 rebranding myself and the internal reform I had, which was a sensitive moment for me. So then in 2018, I’m like, “Man, if n—as can’t see that I’m cold and don’t want to say it, then I’ll say it myself. I’m gonna be obnoxious in a way where I’m repping myself like a graffiti artist.” It’s all purposeful. I wanted to scratch a nerve. A lot of that is me getting to that place where I was just so frustrated and being overlooked. At some point, you take on the underdog role.

Do you walk around saying it randomly? Because I do, especially after playing some of the tracks you’ve produced.

[Laughs.] Yeah, people say that all the time. If somebody calls me, I’ll answer and they’ll be like, “Conductor, we have a problem.”

How did you link with Wiz?

The most exciting record for me this year is the the Wiz Khalifa record with Ty Dolla $ign, “Billionaires.” He texts me, like, “Yo, wait till you see what I did with this.” And I’m like, “You rapping, rapping?” He made that jam. I want people to feel whatever emotion that radiates out.

You still get excited when motherf–kers comes back with some s—t.

Yeah, that’s the best part. How did you find that pocket? Why did you find that pocket? Why did you pick that beat? He was like, “This motherf—ker jam.”

Did you send Wiz a pack?

Nobody gets a nobody a cooked pack. Maybe West. But that’s like I said, that’s always different. Over the winter, I got into Matt Reeves super tough. I started marveling at Matt Reeves and the idea that he had to follow The Dark Knight trilogy. I fell in love with Matt Reeves for that moment and decided to rival that against Bruce Wayne. So, you get tapes like Matt Reeves vs. Bruce Wayne.

And then there’s photos that I found interesting for like color reasons, and then there’s always a note for the artist on why I felt how I felt, so they can see where I was at creatively and then the tape happens. I feel like seeing what another artist is thinking and feeling gives you a moment to collaborate and join them, or find a moment of juxtaposition.

Is there anything that you’re working on this year that we can look forward to?

I think the record with Rome is gonna be another dot on the map, because it’s the entire joint — which we haven’t got much of that for me yet, where I do every song, the arrangement of the track order, how it should feel all the way to the end. We ain’t got that. We just seen me in like little spurts. Now you get to see some dynamic movement all at the same time. Then an instrumental album to drive home.

No matter how far I get or how big the artist is that I work with, I want to keep making those jazz-like records — because honestly, bro, I really feel like that’s where the guy Jay Dee was gonna take it. And I feel a sense of obligation to continue on that path just to see what happens.

Are you planning on doing more full-lengths with rappers?

Maybe three more.

Blondshell, the stage name of Sabrina Teitelbaum, says she named her second album, If You Asked for a Picture, after a line from Mary Oliver’s poem, Dogfish, because it’s “about the idea of how much of yourself do you share with other people.”

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

“Not in the sense of I’m a musician putting out an album and how much do I share with my listeners,” she explains. “It’s, if I’m talking to you person-to-person, and we’re friends, we’re in a relationship or we’re just meeting, how much do I feel like sharing with you? I love the idea that I can just give you a little snapshot, and you’ll get it.”

If You Asked for a Picture, which drops May 2 on Partisan Records, is a series of brave, bold, frank and largely autobiographical snapshots juxtaposed with her trademark crunchy guitar riffs, a handful of ballads and some seriously gorgeous background vocals by hers truly. Take her latest single, “23’s a Baby,” which angrily questions the choices of a young mother — hints in the lyrics suggest its her own, who died in 2018 — but the honeyed aah-aah-aahs that Blondshell, 28, adds throughout the song offset the rancor in a way that creates a fascinating bit of cognitive dissonance: it’s a tragedy that you want to sing at the top of your lungs.

Trending on Billboard

Another grunge-flavored earworm, “What’s Fair,” appears to take more direct aim at a mother, and there are songs about ambivalent relationships, body image and identity, but If You Asked for a Picture — which, like her self-titled first album was produced by Yves Rothman — is beautiful, not bereft, an alt-rock catharsis with nods to the ’80s and ’90s. And though Blondshell says that the lion’s share of her songs come from personal experience, the back stories are not up for discussion: She wants her fans to develop their own snapshots with her music.

If You Asked for a Picture is the latest high water mark in a fruitful year for Blondshell. Last spring saw her release “Docket,” a standalone banger with Bully (Alicia Bognanno) that has racked up 4.3 million plays on Spotify, and a hypnotic cover of Talking Heads‘ “Thank You for Sending Me An Angel,” which was among the standout cuts on last year’s Stop Making Sense tribute album.

In this sitdown with Billboard, Blondshell discusses her love for the Heads, her collaboration with Bully and a number of ideas, inspirations and concepts behind her new album. (This interview was edited for length and clarity.)

You’ve said this album is about asking questions of yourself. What state of mind were you in when you wrote these songs?

The first songs on the album are the first songs that I wrote for the album, so I wanted it to feel like picking up where I left off. I wasn’t intentionally feeling like, oh, I want to ask questions in the songs. It was after the fact that I thought, I guess I was asking more questions than making declarative statements. On the first album. I felt, if I’m going to record and put out music, I must be a thousand percent sure about what I’m saying. By nature of being a little bit more confident [this time], I was able to be like no, I don’t have to know one hundred percent. I can ask, is this relationship working? Is this how I want to live my life? All these different things that were coming up.

You’ve established a recognizable sound, and yet, on this album, that sound is more expansive.

Yeah, I did not want to have some huge departure. I needed to think of it as another 12 songs. But there were things [on the last album] where I thought, I would have done that differently. For example, I’m a huge background vocals person. That’s my favorite part of Fleetwood Mac and all these records that I really love. I love how it’s a whole landscape. Before we even started, I knew I wanted that to be a massive part of the record. I also wanted there to be more textures. Last time, we had a couple of textures on the record that helped define that album. I wanted those, but I also wanted new ones.

Were you inspired by any artists you were listening to in the lead-up to writing and recording?

It’s always what I happen to be listening to around that time. I was listening to a lot of R.E.M. Obviously, they’re this celebrated rock band, but it’s really about the songwriting. They’re comfortable having these big, fun, rock songs — but also “Everybody Hurts.” So, I felt I had more permission to do the big rock band thing and ballads, too.

The lyrics on both of your albums paint very personal scenarios. How autobiographical are your songs?

Like 99.9% is autobiographical, and it’s often about people that I love.

So, “23’s a Baby,” is about someone you know having a baby at a very young age?

Kind of. There’s also conceptual stuff that comes up.

You’re being metaphorical as well.

Yeah, that happens, but the only way that I can write is to write about stuff that I feel the biggest feelings about. I wouldn’t personally feel that way if I were able to just pull it out of the air. It all has to come from somewhere.

One of the things that I love about your music is that you use unusual words in your lyrics, like “docket” and “assessment,” “sepsis” and “Sertraline.” Are you aiming for that literary quality?

No. I never think, “Oh, is this how I want to say this?” The way that I write is so stream-of-consciousness — it’s just stuff that comes to mind. It’s as if I were talking to you, but I’m saying things that I wouldn’t feel comfortable saying to you or my friends or my family. They’re unspoken things — concerns that I have never voiced, or the things I’m embarrassed by, or the feelings I’ve never felt comfortable saying to somebody. It’s just done in a really conversational way.

So, it’s easier for you to say things in a song that you wouldn’t say person-to-person?

For sure.

Man, that is brave.

Yeah — and then it sucks, because everyone ends up hearing it. It’s the stuff I wouldn’t have said to my family or somebody I’m dating or somebody I used to date, or my friend who I’m not friends with anymore. It’s stuff that I wouldn’t have said, because it’s harsh or it’s embarrassing or whatever, and then they end up hearing it. That’s the hardest part of the whole thing. In a way, I have to pretend that’s not happening.

So, you’re not thinking about what the reaction might be?

Yeah. Also, I’m friends with a lot of musicians., and everybody knows that’s how it goes.

Speaking of literary influences, I was wondering if your line about “steely danification” in “Toy” is a reference to William Burroughs or the band.

It’s a reference to the band. I love Steely Dan.

There’s a recurring theme in your songs, such as “Docket” and on this album, “Two Times,” about being ambivalent about a relationship. In “Two Times,” you sing, “Once you get me, I get bored.” Do you struggle with that?

If you haven’t historically had the healthiest relationships, being in a healthy relationship can feel like, “What’s going on? What’s missing?” I also think that every form of media tells people that the valuable quality of a relationship is the conflict. Every movie I saw growing up, every TV show I watched growing up, songs — everything — relationships [revolve around] a problem. So, if your relationship is pretty absent of problems, you’re like, “What’s wrong here? We’re supposed to be fighting and then making up. What if we’re not fighting that much? Do we just not care? Is this a tepid kind of situation?” I have struggled with that.

Like the line in “Two Times”: “I’ll come back if you put me down two times.”

Yeah. Maybe if you’re a little mean I’ll be more comfortable.

How did “Docket” with Bully, Alicia Bognanno, come to be? That’s such a great song.

I love Alicia. She’s so good. I went on KEXP in the summer [of 2023], and they were asking me what I was listening to. Her record had just come out, and I was obsessed with the song “Change Your Mind.” I talked about it, and I think people [told] her. Around the time that I made this album, I wrote the first part of that song and thought I should have Alicia on this song. She wrote the second verse, and we recorded it. She has such a good voice. It was maybe the first time that I’ve listened to someone’s voice a lot and then gotten to hear it in the studio and been like, oh s–t, that’s actually her voice! So powerful.

Would you ever consider touring together? That would be an amazing double bill.

I think that would be so cool.

I have to ask you about the line in “Event of a Fire”: “Pin me down with Styrofoam. Cut out one single mouth hole for air.” Can you elaborate on that?

The whole song is about feeling suffocated by normal life. In some ways, the whole album is about how just everyday life can feel suffocating — feeling stuck in patterns and like maybe I don’t have the permission to feel as much as I feel about this thing that everybody deals with. Feeling shame about feeling so much about everyday normal life. In some ways, the song is also about bigger things — being a 16-year-old girl and figuring out how I feel about my body and figuring out how I’m supposed to look and feel. The part you’re asking about — I had written the whole song, and then when we were recording the guitars, I felt kind of inspired, wrote that and tacked it on at the end.

Does any of that struggle have to do with being a public figure?

No. I don’t even feel that way. I’ve always felt this way, and I think everybody feels that way to some extent. Things like body image are such universal struggles for people. It’s helpful for me to talk about these things — and as a listener, it’s helpful if I hear other people talk about it. All the stuff on this record is stuff I’ve dealt with my whole life.

Do you still you struggle with body image?

I think it gets better as you get older. I’m 27. I was 25 when I made the last album, I really attribute all that stuff to a younger voice. I remember watching Eighth Grade. It came out [in 2018]. There’s this scene of her going to a pool party where she panics, and I remember that’s how I felt at that age. For me, that’s gotten a lot better as I’ve gotten older. But it’s such a universal side effect of misogyny.

You identify as queer, and lyrics in “Model Rockets” implies that you struggle with your identity as well: “With a man I’m only gay, when I’m with a girl I’m lying.”

Again, it’s like that same age where I saw gay people, and I saw straight people on TV, but I didn’t see people talking about so much nuance. All that stuff is from the same time period.

What do you make of the Trump administration’s announcement that it recognizes just two genders?

It’s devastating. It’s going to have consequences for so many people in the most truly heartbreaking ways. Tragic for trans people and queer people — tragic for everybody. The loss of culture and safety. There will be effects for a really long time and it’s terrible.

That’s just a start.

And f–k them.

What are you reading these days?

I finished All Fours by Miranda July last night. It’s so good. I had heard so much about it, and sometimes it’s hard to read a book that has all this hype around it. By the end, I was like, “She’s a genius.”

What about watching, listening?

Severance. A new episode tonight. Are you watching?

I just can’t get into it.

Really?

Admittedly I’ve not seen the earlier seasons. For me, it’s Groundhog Day in a sterile setting.

I get that. Yeah, it is so sterile. I’ve heard people say that they don’t feel comfortable watching it because it’s so austere and just angles and cold. But I’m really into it. I’m also watching White Lotus. I’m happy to be in that world. I think the writing is good. I saw Mike White’s season of Survivor recently. It’s tough for people who work in entertainment on Survivor. There’s a target on their back.

Wait a minute. Mike White was on Survivor?

Oh, yeah. You’ve got to watch it. He’s really smart and he’s really good.

Does he win?

I can’t tell you. You’ve got to go watch it. I don’t want to ruin it for you.

Your version of Talking Heads’ “Thank You for Sending Me an Angel” is fantastic. How did that come about?

Someone mentioned to me in passing that they were doing that tribute album, and I am the biggest Talking Heads fan. They’re one of the best bands of all time. And Stop Making Sense is just amazing. I went to see the movie that they had restored in 4K at a place called Vidiots in L.A. I watched the Q&A. Kim Gordon was the moderator, which was so cool. I got to meet them, and everyone seemed chill. They were all really nice. And then, like a week later, someone asked us to do it. I was like, “F–k yes, let’s go.”

Are you looking forward to your tour?

I’m really excited for my tour. When I made the last album, I really wanted it to feel like a live record. I was so excited to play it live, but I hadn’t toured that much. Now I’ve played with the band a lot for the last two years. We played like 90 shows in 2023. And we made this album with touring in mind — the arrangements and the cadence of the album. I’m stoked to play it live.

In March 2023, Young Gun Silver Fox played in Los Angeles for the first time, selling out a show at the Troubadour. Though the duo is U.K.-based, the pair have an uncanny mastery of the sound that gushed out of elite L.A. recording studios in the second half of the 1970s — polished, wistful, harmony-soaked, groove-based pop. After releasing three albums, earning the opportunity to perform in the birthplace of their beloved style felt momentous. “That was like taking the music back to its spiritual home,” says Shawn Lee, one of Young Gun Silver Fox’s co-founders. Several of the duo’s devoted followers felt similarly: “We had people coming out from Europe saying, ‘we wanted to see you play in L.A.’”

Young Gun Silver Fox will release its fifth album, Pleasure, on May 2. For listeners who see the West Coast ecosystem that incubated hits for Michael McDonald, George Benson, Christopher Cross and Michael Jackson as a pinnacle of pop, Young Gun Silver Fox represent “the modern day gold standard,” according to Greg Caz, an American DJ who specializes in rare groove, yacht rock, and Brazilian music.

Trending on Billboard

“The best Young Gun Silver Fox songs stand right next to anything that was done in L.A. circa 1978 and 1979,” Caz continues. “You could swap them in for an Ambrosia record or a Kenny Loggins record or a Pages album” — which Caz does in his sets.

In decades past, faithfulness to this source material might not have garnered high praise. “For a lot of critics back then, there was a whole view of this style of music as corporate, empty, too slick, too smooth,” Caz notes. “It just felt too good to people, too candy-sweet,” jokes Terry Cole, founder of the soul and funk label Colemine Records. Critics “didn’t feel nearly enough angst.” (Cole partnered with Young Gun Silver Fox to release 2020’s Canyons in North America through his Karma Chief subsidiary.)

That negative view persisted for decades, blending with the late 1970s disco backlash into a potent cocktail of rejection. “I fully expected to be totally forgotten by the end of the 1980s,” McDonald said in the recent movie Yacht Rock: A Dockumentary.

It’s not surprising, then, that when Young Gun Silver Fox started writing their debut album, 2015’s West End Coast, they felt that “there wasn’t a band that was reclaiming that music as their own,” Lee says. While that meant that Lee and his co-founder Andy Platts’ efforts were often overlooked, there are advantages to running your own race. “It felt wide open,” Lee continues. “We had the luxury of doing something that nobody else was doing at that time.”

In an about-face, though, music that was once derided as “dad rock” — or described glibly as “yacht rock” — has now been reappraised and embraced. Some listeners “come to it jokingly,” says one of the commenters in Yacht Rock: A Dockumentary. “But then you suddenly find yourself appreciating it sincerely.”

It remains to be seen if that newfound goodwill extends to modern purveyors of this classic sound. But if it does, few groups are better positioned to benefit than Young Gun Silver Fox.

“They’re gaining momentum now,” says Tom Nixon, co-host of the podcast Out of the Main, which focuses on “yacht rock, west coast AOR, and related sophisticated music.” “This stuff is extremely popular in pockets of Europe, specifically the Northern parts, and in Japan — more popular than it is in the United States. It’s still gaining in popularity here: When I joined the yacht rock Facebook group [six years ago] it had 5,000 members. Last time I looked there were 168,000.”

In conversation, Lee is grizzled and gregarious, quick to cackle, and prone to starry-eyed digressions about music’s overwhelming power and his partner’s formidable songwriting chops. Platts is more reserved — though not on record, where his voice is remarkably pliant, capable of head-turning, Jackson-indebted leaps (“Moonshine”) and meticulously soothing multi-part harmonies that reach for Crosby, Stills and Nash (“Sierra Nights”).

The duo typically write and record parts separately — while they’re both based in the U.K., they live about two hours apart, and also pursue other musical projects — and email them back and forth until they end up with a finished song. But this process stopped working when they began to craft the follow-up to 2023’s Shangri-La. “On the previous albums, when we started the first few tracks, you almost could smell what the record was going to be, see the blueprint for where it could go,” Platts says. This time around, though, he felt he “wasn’t getting there.”

So the pair tossed convention out of the window and agreed to meet for in-person writing sessions. This approach immediately proved fruitful — on day one, Lee and Platts knocked out the instrumentals for three tracks that made it onto Pleasure, including the first two singles.

With each of their past albums, Young Gun Silver Fox aimed to “change the palette,” as Platts puts it — clearing room for more horns on Canyons, injecting more acoustic guitar into Shangri-La. With Pleasure, they wanted to make sure the pace didn’t sag. “Downtempo stuff is really easy to relax into,” Lee explains. “You don’t want to be lazy and play a whole set of dirge classics.”

There’s nothing dirge-like about “Just for Pleasure,” which reaches for the heights of disco-era Heatwave with its beefy three-note bass and thwacking drums. And the second single, “Late Night Last Train,” hums at an unimpeachable frequency, propulsive but misty-eyed. Platts called this blissed-out territory “Fleetwood Mac meets Delegation” on Instagram.

“Every one of our albums has a song that lives in that world,” Lee says. “We know there’s gold in them thar hills,” he adds, cracking himself up.

Young Gun Silver Fox will follow Pleasure with another U.S. tour in the fall, playing in 500 – 700 capacity rooms. Hardcore fans love that they are “keeping the fire” for that glorious L.A. studio sound. (“Keeping the fire” in place of “carrying the torch,” according to Nixon, because it references a Loggins song.) But the duo are primarily focused on meeting their own high standards. “I just keep the field of vision to me and Shawn,” Platts says. “If this record is good, then everything else doesn’t really matter, as long as we got that right.”

With Pleasure, initially “we weren’t getting that right,” he adds. “We needed to switch it up for something to happen. And then once we did that, and we finished, it was like, ‘Ah! You have the thing again.’”

Even the most patient and forgiving of Wolf Alice fans have had to learn how to love at a different rhythm than the fans of other artists. Waiting for a new record, without knowing if anything is coming at all, seems to have become a primary act of their devotion. “Is it over?” exclaimed one despairing Reddit user a few months back, exasperated by the British rock band’s radio silence throughout 2024. “No more music?”

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

On April 22, after a near four-year wait, an eon in an ever-changing industry, their qualms were put to rest. Breaking cover, all posts on the London four-piece’s Instagram page were swiftly archived, while its previously dormant TikTok account began to flicker into life. Soon enough, a carousel of striking, retro-leaning images — including bassist Theo Ellis wearing a leather jacket adorned with a gem-encrusted ‘Wolf Alice’ motif — was uploaded with a call-to-arms caption: “We’ve missed u.” Major festival slots at Glastonbury and Radio 1’s Big Weekend, meanwhile, were also confirmed for the summer.

Trending on Billboard

Offering a glimpse of what may lie ahead, it’s a new look for the band, and a new way of marketing its music, heralding in the group’s next era with aplomb. Unlike most contemporary acts subject to mass idolatry, Wolf Alice’s online presence (which, historically, has been minimal) has never been part of the appeal. Dozens of accounts have instead become dedicated to posting whatever updates they can find, often rehashing photoshoots from their early career.

In a world of algorithm game-playing and lyrics bundled with gossipy subtext, the band’s songs — which deftly blend garage rock and shoegaze — function as talismans affirming the importance of standing tall by your convictions. The subtlety and class with which they choose to signal meaning to their audience is something that has long defined their music; in knowing relatively little about the band’s own inner lives, fans’ desire to get closer only grows stronger.

Young, terminally online pop fans feel drawn to the notion of artist folklore, having grown up watching the likes of Taylor Swift and Ariana Grande incorporate “Easter eggs” (hidden messages and references) into their videos. It’s an idea that extends to other genres that are popular in stan culture forums, where lost songs and “will-they-won’t-they” social media teasers are analyzed feverishly. In the case of Wolf Alice, the group has earned a committed Gen Z fanbase who gravitate toward them as much for the element of surprise as they do for the music.

The anticipation around the band’s next steps, therefore, couldn’t be greater. Wolf Alice’s last record, 2021’s Blue Weekend, ushered in a new commercial zenith, landing a nomination for the Mercury Prize (which the group won for 2017’s Visions of a Life), topping the Official U.K. Albums Chart and leading the band to its first-ever BRIT award the following year. The campaign steamrolled ahead across a further 12 months, during which they opened up for Harry Styles in stadiums across Europe and completed an extensive headline tour.

In 2025, each of the members are now approaching their mid 30s. No longer the wild-eyed 20somethings they emerged as with fiery 2013 EP Blush, they have spent the past decade quietly unlocking emotional discoveries in their songs, flowing with their shifting perspectives on ambition and desire. Across three studio LPs, it’s become clear that guitarist and lead songwriter Ellie Rowsell focuses on growing privately in order to bloom publicly; she can do huge indie hooks with the best of them (2015’s “Freazy” or the endlessly affecting “Don’t Delete the Kisses”), but has never sounded quite like any of her peers because of the strength of character at the center of her work.

Consistently ducking the expectations of indie’s upper echelons — the ones which the band vaulted into with 2015’s My Love Is Cool — has only further affirmed Wolf Alice’s influence and longevity. You can see the band’s gnarly, incisive showmanship in the likes of Wunderhorse or rising stars Keo, or hear the band’s incandescent take on indie throughout You Can’t Put a Price on Fun, the debut EP from Manchester-based artist Chloe Slater. “Seeing them live was the most joy I’ve ever felt,” the latter recently recalled of a formative Wolf Alice gig, which she credits with changing the course of her burgeoning career.

Intriguingly, the band’s period of downtime was interrupted last year with the announcement that it had left its longtime label home of Dirty Hit — home to The 1975 and Beabadoobee — to sign with Sony imprint Columbia. According to a report from The Independent, the move stemmed from the members wanting “to experience something different,” having previously been in the same deal for nearly a decade, and that Rob Stringer (CEO of Sony Music Group) “is a huge fan” of theirs.

Though Blue Weekend was rapturously received by critics, with The Observer describing it as “alchemically good,” the question of whether the band can level up to festival headliner status has long hung over reviews of its electrifying live performances. Groundbreaking things can happen if a band is given the time and space it needs to truly develop into greatness, and one can hope that with the support of a major label and a new team around Wolf Alice, the group’s music will be able to travel further than ever. It’s fascinating to think what they might do next.

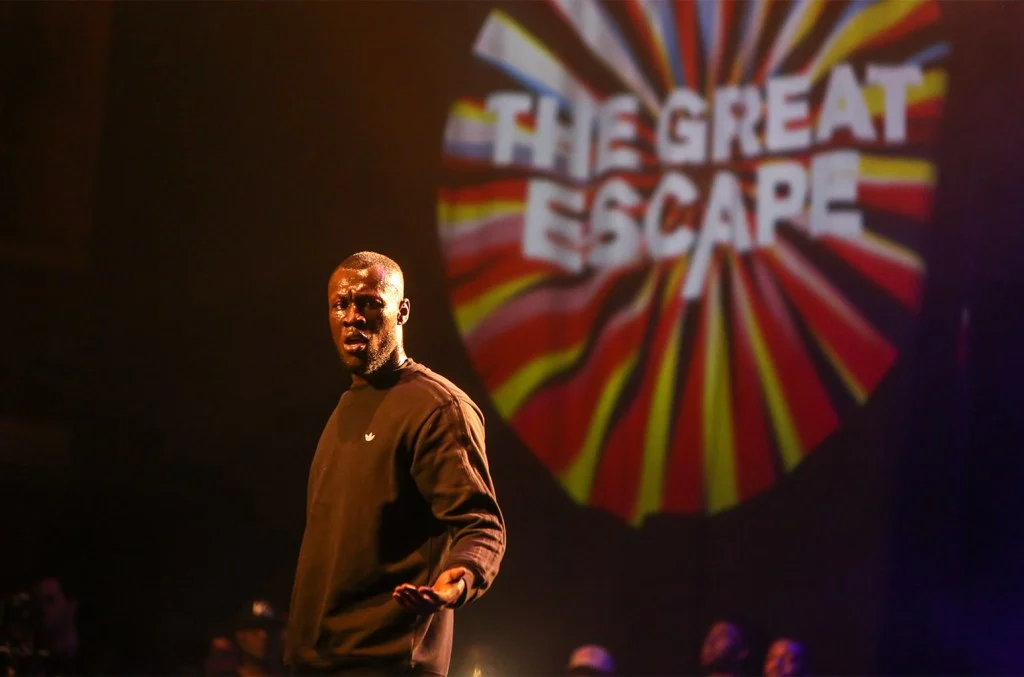

The Great Escape annually signals the start of U.K. festival season, as Brighton turns into a mecca for new sounds each May. Recognized as Europe’s biggest hub for new music discovery, the event welcomes everything from must-see cult acts to leftfield oddities and rising stars to the seaside – encapsulating pop, rap and folk to […]

On Friday and Saturday (April 25-26), hundreds of young professionals got a look behind the veil of the music industry with some help from Grammy winners Coco Jones, Samara Joy and Laufey — as well as the Recording Academy’s New York chapter.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Hosted at Racket NYC in Chelsea, the Mastercard-presented 2025 Grammy U Conference featured two jam-packed days of networking opportunities, panel discussions, headshot stations and various activations spearheaded by industry professionals across disciplines. The two-day conference aimed to educate 18-29-year-olds actively pursuing careers in the music industry. From publicists and songwriters to DEI coordinators and engineers, virtually every music industry field had a representative at the sprawling conference.

Jones, who released debut studio album Why Not More? on the same day, headlined the first day of the conference, participating in a lively, edifying panel hosted by Grammy U Atlanta chapter representative Jasmine Gordon. Titled “Crafting A Multifaceted Career,” Jones’ panel provided the audience with an honest look at how she balances her multi-platinum musical career with her robust acting portfolio.

Trending on Billboard

Many students in the audience grew up alongside Jones as she transitioned from Disney starlet to Grammy-winning R&B siren — she took home best R&B performance for “ICU” in 2023 — so her industry insights felt particularly pertinent. From stressing the power of positive affirmations (“You gotta be delulu till it’s true-true!” she quipped) to the benefits of an entrepreneurial DIY mindset, Jones dropped several gems during her talk, while excited audience members quoted lyrics from her hours-old new album.

“The Grammys and the Recording Academy do so much for creatives that I want to help shine a light on,” Jones told Billboard minutes before she graced the stage. “The awards are obviously life-changing, but it’s also about keeping the lights on in that apartment while you’re writing songs. It’s also about helping somebody further their education on what this business is really like. I feel like it’s my duty to help highlight that. I see myself in these students.”

Following Jones’ chat, Grammy U mounted two additional panels — one on the world of sync licensing, and another on the evolution of influencers and digital media — before breaking for the day at 10:00 p.m. E.T. Bob Bruderman, Blu DeTiger and Riggs Morales led the panel on sync licensing, A&R and brand partnerships, while content creators Davis Burleson, Anthony Garguila, Julian Shapiro-Barnum, and Jonathan Tilkin headlined the night’s closing panel.

Pop-soul band Lawrence, who scored a divisive viral hit on TikTok with last year’s “Whatcha Want,” kicked off the conference’s second day by sharing an unflinching look at the studio sessions for their 2024 album Family Business. Band members Clyde Lawrence, Jordan Cohen and Jonny Koh projected their ProTools sessions and broke down how Tower of Power’s influence, hours of improvisation, ambitious songwriting collaborations and meticulous mixing of live and programmed drums gave way to album cuts like “Hip Replacement” and “Death of Me.”

Icelandic-Chinese jazz-pop star Laufey, who won the traditional pop vocal album Grammy for Bewitched in 2023, closed out the day with an equally charismatic and insightful keynote panel, moderated by TikTok game show “Track Star” host Jack Coyne. In their discussion, Laufey stressed the importance of her classical music foundation, detailed her Coachella debut alongside the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and explained how she found the fearlessness to write songs across a range of genres.

“Growing up, I felt like there wasn’t quite enough transparency on how the industry worked, how teams and artists are built, how you build and sustain a career, all of that,” she told Billboard shortly before her panel. “I was so recently a student that I felt this need to talk to kids who are in my footsteps and be transparent about what it’s like and show all the different opportunities that are available.”

Laufey, who dropped her “Silver Lining” single earlier this month, also treated the Grammy U Conference to the first-ever performance of her forthcoming new single, “Tough Luck.” Billed as an “angry, f–k you” song, Laufey performed the track accompanied by just an acoustic guitar. “You say, ‘I can’t read your mind,’ but I’m reading it just fine/ You think you’re so misunderstood, the black cat of your neighborhood,” she crooned, nailing her debut performance of the track.

After a break, the conference reconvened at the iconic Bowery Electric for a Grammy U & DEI showcase, headlined by five-time Grammy-winning jazz sensation Samara Joy. Before the Bronx native took the stage, three talented Grammy U performers — selected in collaboration with the Recording Academy’s New York chapter — treated the crowd to impressive sets. Neo-soul crooner Isea, saxophone-fronted jazz band The Jax Experience and new-school rock band The Millers all repped the region well, with each act winning over several new fans by the end of their performances.

Of course, Joy brought the house down with a rousing set comprised of cuts from her 2024 album Portrait, including standout tracks “No More Blues” and “Peace of Mind / Dreams Come True.” With upcoming performances in Brazil (Aug. 2) — while speaking with Billboard before her performance, she teased a forthcoming bossa nova-influenced single in which she may be singing in Portuguese — and at New York’s legendary Carnegie Hall (April 30), Joy reminded the Bowery crowd why she’s one of today’s most celebrated live vocalists.

“I’m inspired by my peers and folks younger than me who are passionate about music. I want to be in spaces where I’m surrounded by like-minded people,” she told Billboard moments before lighting up the Bowery Electric. “That’s what my band is, I like presenting that collaboration and sense of community as we develop and grow.”

As diversity efforts and arts education continue to face relentless attacks, the 2025 Grammy U Conference helped equip the next generation with the necessary insight to shape and protect the industry’s future.

Young Thug is officially back. Today, he dropped a new song and video, “Money on Money,” featuring one of his favorite collaborators in fellow Atlanta native Future. The two superstars channeled Watch the Throne‘s classic “Otis” music video where Jay-Z and Ye (formerly known as Kanye West) dismantled a very expensive car and welded it […]

BRONCHO’s frontman, guitarist and primary songwriter Ryan Lindsey is walking around a room in his new Tulsa, Oklahoma home with a yardstick over his shoulder while somehow conducting a Zoom interview. He explains that he is “hanging things on the wall that need hanging, along with some “light baby proofing” in the room, which he calls his “Imagination Station.” The drywall is unpainted and sealed with white spackle, and the recent father of two says he is considering keeping it that way “because whoever spackled that room did such a great job, I’d hate to cover it up.”

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Lindsey is not a fan of ornamentation, and BRONCHO’s fifth full-length album, along with its title, Natural Pleasure, makes that clear. The record, which drops April 25, marks a major departure from the Tulsa-based band’s previous albums. Unlike its previous release, 2018’s Bad Behavior, which offered up a harder-edged blues-washed sound, or its bop-tastic 2014 indie classic single, “Class Historian,” Natural Pleasure is a hazy, dreamy, organic sounding confection where the music takes center stage, and the lyrics can be harder to determine than The Kingsmen’s version of “Louie Louie.” Although BRONCHO’s muscular rhythm section — drummer Nathan Price and bassist Penny Pitchlynn — front the mix, Lindsey’s whispery falsetto and his and Ben King’s gentle guitar work set the tone for a soothing, record that’s perfect for these troubled times. Edible optional.

Trending on Billboard

As he wandered his Imagination Station, Lindsey told Billboard why five years elapsed between Bad Behavior and Natural Pleasure, how fatherhood has affected his artistic process, and recalled his trippy visit to Elvis Presley’s Graceland. (This interview was edited for length and clarity.)

It’s been seven years since BRONCHO’s last album. Why so long?

You know, it’s weird. When I hear that number, it sounds way larger than the amount of time in my mind that it took. I think the pandemic made time bend a little differently. That whole foggy period took up a big chunk of time. Part of it is also that my girlfriend and I had a kid in 2022. Building up to that, I was like, “OK, I’ve got to finish this record before he’s born.” I didn’t finish it. Then it took some time after him being born for me to get back in that zone. Then we found out we were having another kid, and I was like, “OK, I’m really going to finish it before he’s born.” Right before he was born, I was finished, and he just turned one.

Broncho

Courtesy Photo

How does your artistic process work in terms of the other members of BRONCHO?

The songs live in my head first. They are on a loop in my mind and in my world for a while. Then at some point, either we get together, or I start recording stuff and sending it to everybody. Then we get in our friend Chad Copelin’s studio in Norman [Oklahoma], who we’ve done every record with. It’s just a couple of hours away. We see what makes sense in that realm, and it’s a mixture of adding things, maybe trying new versions of things and then coming back to the original tuff that really felt good. Lots of times we end up using a pretty good chunk of that stuff because we can’t beat it.

The album has a dreamy vibe. Where was your head at when you were writing these songs?

I was actually writing them was before I even knew a kid was coming. Like, “You Got Me.” It’s as though I was writing about my kids, but I hadn’t even found out we were having them yet. Weird stuff like that happens in the writing process.

You wrote the line “You’ve got me and you’ve got your mom” before you knew you were having your first child?

Yeah, I had no idea where it was coming from, but it all felt so right that I figured, maybe it’s about our cats. Then Jessica tells me we’re having a kid, and I was like, well, that’s crazy. I just wrote him a song. I think something from somewhere was giving me the heads up that he was on his way.

A lot of songwriters and artists say that their work seems to flow to them from some sort of divine power.

Every time I hear someone speak that way, it makes total sense to me, because I think the process is about being open and letting something come in. I don’t know if it’s come in from my own mind or from the other side of the veil or wherever. But I’m open to it, and things stick around in my head and loop over and over. Whatever lasts the longest through that period is the stuff that ends up being used.

Your bio for this record says that the song “Original Guilt” is about inheriting Christian guilt from the part of the country where you live?

I grew up in a religious world, and so I think guilt is just something you just have. I feel guilty, and I try to have the most fun with that that I can. That song happened just like any of our other songs. When the melody feels right and is looping in my mind, or playing and singing dummy vocals over and over, certain words start to appear. For whatever reason, “original guilt” just came out, and I thought, I know this. It’s like you’re digging slowly for bones and trying to not disturb the bone that you want intact. But there’s a lot of stuff to swipe away.