feature

Trending on Billboard

Mention Jeff Price‘s name in a room full of music executives and some will almost certainly wince and say that he is a troublemaker — an entrepreneur who enjoys noisily lashing out at those in the business he perceives are not doing right by music artists, songwriters, comedians and other creators.

Most conspicuously, that sense of righteousness has manifested in a two-year on-and-off email battle — often with journalists, including this reporter cc’d — with the Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC), the nonprofit organization established by the Music Modernization Act (MMA) to administer blanket licenses for digital streams and downloads in the United States.

Related

Price claims that deficiencies in the MLC’s operations have deprived clients of his current startup, Word Collections, royalty payments, and, in other cases, have delayed payments.

What Price’s critics rarely acknowledge is that Word Collections is the third successful business that he has built as a result of his indignation. “It’s usually a combination of something that I’m frustrated with, combined with having an opportunity in my professional career to correct it,” he says of his entrepreneurial ventures.

For example: Price founded TuneCore in 2006 to help DIY artists and indie labels get their music onto digital platforms for a fraction of what it previously cost. Then, in 2013, he started Audiam, which claims YouTube publishing royalties for DIY songwriters who, in many cases, are uninformed about music publishing and how to get paid for their work. And he established his latest venture, Word Collections, in 2020 to fight for and collect mechanical royalties for comedians’ recordings, which many digital services were not paying at the time.

Although Price admits he departed the first two companies under unpleasant circumstances — possibly due to his combative nature — TuneCore and Audiam were successfully sold. Word Collections is still in a growth phase, but many of Audiam’s investors are helping to fund it — proof that he remains a bankable entrepreneur.

Related

And these investors are not small players. Key among them is Black Squirrel Partners, the investment division of Metallica’s business operations. The band and Black Squirrel were a client and investor, respectively, in Audiam and followed Price to Word Collections, which now also represents music artists. (Pop artist Jason Mraz is among other investors who did the same.)

The reason: Black Squirrel principal and partner Eric Wasserman says that while at Audiam, Metallica’s income “went from a small amount to a significant portion of the revenue from their [intellectual property].”

The band apparently is happy at Word Collections as well. In July 2023, Price and Word Collections closed on a $5 million investment round led by Black Squirrel, which became its lead investor. “We are very enthusiastic about this company and Jeff’s leadership,” Wasserman says. “Word Collections is doing a great job representing the Metallica catalog.”

Other Word Collections clients include Greta Van Fleet, The Offspring, Grace Potter, Thomas Dolby, Galactic, John Oates, Switchfoot, Richard Marx and the estate of Johnny Marks, among other songwriters. Word Collections, which employs a staff of 10, also represents the comedy catalogs of Robin Williams, George Carlin, Margaret Cho, Jerry Seinfeld and Billy Crystal, among others.

Related

Because of his history of saber-rattling, Price acknowledges that industry executives have accused him of being an opportunist looking for industry problems so that he could profit from those issues.

“Yes, it [can be] a business opportunity, but that’s usually not the driving force,” he says. “It isn’t like, ‘Ha ha, here’s this thing, let me go make money off it.’ It’s more of, ‘This thing is not right, let’s fix it,’ which also happens to be a business opportunity.”

Metallica

Ross Halfin

‘That’s stealing in my mind’

Slim with gray hair parted in the middle, Price does not resemble a street fighter. He even sports a broad smile in his LinkedIn photo. Of all the stands he has taken against the industry, he is best known for publicly opposing — and loudly criticizing — the MMA, which passed in 2018 and dramatically changed digital music licensing and how payments are made for compositions. He was even part of a group, which dubbed itself the American Music Licensing Collective (AMLC), that vied against the National Music Publishers’ Association’s (NMPA) preferred assemblage of major music publishers to be designated the MMA’s administrator of digital licenses.

The U.S. Copyright Office went with the NMPA-backed team — now known as the MLC — but not before Price had alienated several of the industry’s legacy players.

While the passage of the MMA was largely hailed as a beneficial game-changer for songwriters, Price alleges that the law created a form of legal theft that benefits large publishers. That’s because songs for which the publisher or payout instructions cannot be determined are designated as black-box monies — they are also called unmatched or unclaimed royalties — and if the rightful recipient cannot be determined within three years, the MLC has the authority to distribute these monies to publishers based on their market share.

Related

Unmatched royalties total hundreds of millions of dollars annually, and Price contends that the bulk of them are generated by DIY creators who don’t know how to properly register their songs with the MLC. Worse, he says, if those creators learn belatedly that their royalties were distributed elsewhere, they cannot retroactively claim them, because according to the text of the MMA, distributions of unclaimed and/or unmatched royalties “shall supersede and preempt any state law (including common law) concerning escheatment or abandoned property, or any analogous provision, that might otherwise apply.”

“I believe [digital services] should get a license and pay a commensurate royalty, and the entity that earns the royalty should get the money,” Price says. “The other side is like, ‘We don’t want to do that. Why don’t we just take all this money that’s not getting paid and hand it to ourselves based on a black-box [market-share] allocation?’ And that’s stealing, in my mind.”

However, the MLC has yet to use this market-share mechanism to disburse any black-box monies, which have been accumulating for the last eight years and predate the passage of the MMA.

Price has other issues with the MLC, and in addition to the blizzard of emails he has sent its CEO, Kris Ahrend, and other executives there, his complaints are collected in a 53-page memo submitted by Word Collections that opposes redesignating the organization as the administrator of blanket compulsory mechanical licenses “without significant policy and governance changes to achieve the [MMA’s] intended goals and objectives.”

Related

Word Collections’ memo is one of 63 posted on the U.S. Copyright Office website as it conducts a mandated periodic review on whether the MLC should be redesignated. While other submissions suggest improvements, the overwhelming majority support the MLC’s reappointment, if the more than 500 publishing companies and industry trade organizations cited in the MLC’s own filing are counted. Among those in favor are Warner Chappell Music, peermusic, the RIAA, the Recording Academy, the Academy of Country Music, the Association of Independent Music Publishers and the NMPA.

The MLC declined to comment, but industry executives say in its defense that the organization is dealing with a vast amount of data and, as a result, its execution “will never be flawless or perfect,” as one music publishing source puts it.

In the early days of streaming, Price’s squeaky-wheel approach earned him grudging respect as a renegade. But over the years, his detractors have grown in number, and some say they are weary of his unyielding combativeness, even if he is right.

‘The messenger being the problem’

One executive says Price “is a classic example of the messenger being the problem, not the message,” explaining, “While he is really trying to get the most money for songwriters, the way he has gone about highlighting these issues pisses off everybody.”

An executive in the digital music realm calls Price “litigious.” In reality, Price has not directly sued any digital services, but through data supplied by his company, he was involved in songwriter lawsuits filed against Spotify, including a 2017 legal action led by Camper Van Beethoven founder and musicians’ rights activist David Lowery that resulted in a $45 million settlement, and others by Four Seasons member and songwriter Bob Gaudio, Bluewater Music, and Dolby.

Word Collections’ data was also used in lawsuits filed by a number of comics against Pandora, including Andrew Dice Clay, Bill Engvall, Ron White and the estates of Carlin and Williams. Price says his clients usually don’t resort to litigation until a digital service has spent about a year ignoring requests for payment.

Others in the industry offer a more charitable assessment of Price. One executive who has crossed swords with him says he’s “difficult to work with” but concedes that “98% of what he says is correct.” The executive adds, “[Price] is not a lawyer, so sometimes he gets a nuance wrong, but in terms of the important stuff — like how digital services didn’t pay publishing properly and what’s wrong with the system in publishing — he was the only one making noise.”

Related

“I think Jeff is a catalyst and is brilliant,” says Jordan Bromley, entertainment group leader for law firm Manatt Phelps & Phillips. “Guys like him don’t follow rules or lines of politics. They say the quiet things out loud.”

Though Price concedes that he “once” apologized to the MLC for mistakenly claiming it hadn’t paid out Pandora royalties due to Word Collections, he expresses no regret for his unflagging approach to perceived transgressors. “Water on stone eventually makes the Grand Canyon,” he says. “I am working from outside the system to change the system.”

Before entering the music industry, Price lived an itinerant life. His mother founded an advertising agency in the 1970s when it was still a male-dominated business, and they moved frequently for her career. Growing up, he says he attended eight schools in a 12-year period. He also spent time in Japan and Israel, where he served in the latter’s military reserve. He worked as a bartender, sold books out of mall kiosks and was a production assistant for film/TV producer Rachael Horovitz, the older sister of the Beastie Boys’ Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz.

Price, who attributes his rectitude to once witnessing his father stop an attack against another person, entered the music industry in 1991 as a co-founder of the SpinART indie label, which released the music of such indie acts as Frank Black, The Church, Apples in Stereo, The Boo Radleys and Vic Chesnutt before succumbing to bankruptcy in 2007. “SpinART taught me everything I know about the industry,” Price says. “I wouldn’t be able to make informed decisions without the knowledge that experience gave me.”

Related

As iTunes, Rhapsody and other online music stores started up, Price began looking for a digital distributor for SpinART, but says he was angered by the terms he was offered, especially what he considered unwarranted high distribution fees. “Distributors were demanding 15% to 30% of revenue to basically send a digital file to places like Apple and Amazon,” he says. “Overlaying the analog business funnel on top of the digital channel just didn’t make sense.”

Price voiced his grievances in a 2006 issue of Billboard. “I despise the economic model of aggregators. They are morally repugnant,” he said. “On the physical side, distributors work their asses off. They provide co-op opportunities; they’ll have regional sales reps. In the digital world, they don’t provide that service. They’re an aggregator.”

Through his dissatisfaction, Price saw an opportunity to fill a void in the market, and with partners Gary Burke and Peter Wells launched TuneCore in 2006. To date, it’s his most successful venture and remains a major indie player 13 years after he and his partners left the company.

TuneCore’s model was simple and elegant. It initially charged a flat rate of $7.98 an album per year and a delivery charge of 99 cents per song to put titles up on all the digital stores, with all sales revenue going to the artist. By 2010, prices had increased to $49.99 an album per year and $9.99 per song.

Related

Price’s refusal to play by established rules earned him scorn when he created his own International Standard Recording Code (ISRC) — essentially digital fingerprints for tracking royalties — for works released by TuneCore artists instead of paying the RIAA, which, at the time, assigned the codes.

‘Took off like a rocket‘

TuneCore “took off like a rocket and it was a heck of a learning curve,” Price recalls. “All of a sudden, we were doing over a million dollars a month. We were like, ‘Holy crap!’ And then that number became $8 million to $10 million a month. It got crazy how quickly it grew.”

The company eventually needed funding to accommodate that growth and brought in Guitar Center and Opus Capital as investors. But the introduction of private equity blew up management in 2012. Price and some of his staff were ousted, and in 2015, the company was acquired by Believe Music, where it is now one of the largest independent distributors in the world.

While at TuneCore, Price realized that indie artists were not collecting their fair share of music publishing royalties and started a publishing administration division. After his departure, he founded Audiam in June 2013 as, he says, a corrective.

Related

His team built a system that tracked down cover versions of songs and user-generated videos on YouTube and other streaming platforms that included unlicensed recordings of songs. On behalf of its clients, Audiam claimed the songs to collect both publishing and recorded master royalties that were due.

A publisher administrator client of Audiam says, “We may have found 30 cover versions of a song, but when Jeff entered the picture, he said, ‘Here are 225 ISRC cover versions of that song.’ ”

Like TuneCore, anyone could sign up for Audiam, but this time Price’s economic model took an undisclosed percentage of the revenue.

Official videos of a song were easy to find and claim, but songs included in user-generated videos and cover versions performed by DIY artists were not, and Audiam’s success enabled the company to expand into licensing and collecting publishing royalties from other digital platforms such as Spotify and Amazon. But that meant Price was soon butting heads with those platforms’ service agents, like the Harry Fox Agency and Music Reports Inc.

Audiam eventually attracted major artists such as Metallica, Mraz and Jimmy Buffett. Industry heavyweights also invested, including Q Prime co-founder Cliff Burnstein, then-WME head of music Mark Geiger, Victory Records founder Tony Brummel, Distrokid founder Philip Kaplan, Silva Entertainment namesake Bill Silva and Provident Financial Management.

Related

When Audiam’s growth required new sources of funding, Price and his investors agreed to sell the company to the Canadian performing rights organization SOCAN in 2016. But his relationship with the PRO soured, in part because of his vociferous opposition to the MMA and the NMPA’s backing of the legislation that calls for market-share distribution of black-box monies.

When Price and the AMLC team he helped assemble began jockeying with the NMPA’s choice to administer blanket mechanical licenses for the MMA, informed sources say his efforts — which included posting videos to YouTube that questioned the fairness and transparency of music publishing — resulted in SOCAN management taking fire from the mainstream music industry.

SOCAN pressured Price to abandon his protest, sources say, and his relationship with the PRO became further complicated when Audiam’s investors began agitating for an additional equity payout because, they claimed, the company had hit previously agreed-upon profit performance targets.

Price says he resigned due to the equity payout issue, which created a conflict because he was serving as his initial investors’ security representative while also still leading the company. He says he agreed to stay on long enough to help prepare Audiam for a sale, but was terminated before that happened.

Related

Price declines to elaborate but says his parting with Audiam, like his departure from TuneCore, was “unpleasant,” and in 2021, SOCAN sold the company — ironically, to the MLC’s data management agent, the Harry Fox Agency, which is now owned by the Blackstone-owned SESAC Music Group. As for Audiam’s investors, sources say that a lawsuit filed on their behalf resulted in an undisclosed settlement in addition to the initial payout from the sale. (SOCAN declined to comment, as did Eric Baptiste, who led the PRO when it purchased Audiam.)

By then, Price had started Word Collections, which originally focused on comedy streams. He likened comedians’ jokes to song compositions that were deserving of publishing royalties. Up to then, most digital services had been paying record labels for comedic master recordings but not the underlying literary compositions. “That’s what Jeff does,” says ClearBox Rights founder and principal John Barker. “He recognizes when people aren’t getting paid, and he finds a solution.”

After the expiration of Price’s noncompete clause with Audiam, Word Collections expanded into music publishing administration, putting him in competition with his former company. And though TuneCore remains Price’s most successful startup, he claims Word Collections’ revenue now matches the publishing royalty volume collected by Audiam.

Price retains strong opinions on the MMA and gives no indication that he’s ready to ease up on the MLC, certainly as long as publisher market share could be used to disburse black-box monies. But he claims he has dialed back his combativeness on a number of industry issues because much of what he complained about has been corrected.

And in a number of ways, Price is no longer the outsider he claims to be. “It’s an interesting paradox for me,” he says. “We are directly licensed outside North America with the largest digital services in the world, which enables Word Collections to collect mechanical and performance royalties from streams. Wherever we can, we disintermediate the CMOs, the subpublishers and the black boxes in between songwriters and their money. For nondigital, we collect from 104 countries and are direct members in 40 of the music rights organizations in their countries through a joint venture with Nashville publishing administrator Bluewater Music,” he adds. “We work for some of the most important artists in the world and some of the biggest artist management companies and music companies in the world. I like being on the same side of the fence as them.”

Teddy Swims makes history on this week’s Hot 100: “Lose Control,” the singer-songwriter’s soulful pop-rock anthem, spends its 92nd week on the chart, breaking the record that it shared with Glass Animals’ “Heat Waves” as of last week and setting the new longevity mark for the nearly 68-year-old song chart.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

After debuting on the Hot 100 back in August 2023, “Lose Control” only topped the chart for 1 week, back in March 2024. Yet the song remains in the top 20 more than a year later (coming in at No. 11 on the latest chart), after spending a record-setting 63 weeks in the top 10.

“The burn has been minimal,” Alex Tear, Vice President of music programming at SiriusXM + Pandora, tells Billboard of the breakthrough hit’s maintained momentum. “The audience reaction is something that we completely adhere to — subscribers tell us what they want to hear, and how often they want to hear it… And [‘Lose Control’] is still undeniable, pure mass appeal.”

Trending on Billboard

Swims’ smash hasn’t been alone in spending months upon months in the Hot 100’s upper tier. Before Morgan Wallen’s new album I’m the Problem cleared out a sizable chunk of the chart this week with its 29 new debuts, the top half of the Hot 100 was littered with hits that had spent months — and in some cases, over a year — on the tally.

Some of them, like “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” by Shaboozey, “Die With a Smile” by Lady Gaga & Bruno Mars and “I Had Some Help” by Post Malone and Wallen, have stuck around after logging multiple weeks at No. 1; others, like Benson Boone’s “Beautiful Things,” Gigi Perez’s “Sailor Song” and Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso,” never reached the top spot, but have lingered near it since mid-2024. Kendrick Lamar and SZA’s “Luther” may have just spent 13 straight weeks atop the Hot 100 before being dethroned by Wallen and Tate McRae’s “What I Want” this week, but even that smash collaboration spent 12 weeks on the chart before reaching its peak in late February.

The Hot 100 always includes a wide swath of ubiquitous hits — but rarely have so many of those hits endured at once. On the Hot 100 dated May 24, zero songs in the top 10 had spent a single-digit number of weeks on the chart. The average number of weeks spent on the chart by the songs in the top 20 was 30.35 weeks; five years ago (on the Hot 100 dated May 30, 2020), that average was 18.75 weeks. On the recent Hot 100, a total of nine songs in the top 20 had spent 30 weeks or more on the chart; 10 years ago (on the Hot 100 dated May 30, 2015), that total was one song in the top 20.

What’s causing this period of smashes that last forever on the chart? Part of the explanation for the lack of 2025 chart movement is the glut of new pop voices from 2024 spilling over into a new year, says Spotify editorial lead Talia Kraines. “I think that 2024 was such a crazy year for pop music, and incredible new songs and artists, that was years in the making,” she says.

Kraines points to artists like Chappell Roan, whose “Pink Pony Club” is approaching 50 weeks on the Hot 100, and Charli XCX, whose 2020 song “party 4 u” is just now hitting the chart, who helped define the mainstream last year while also boasting ample back catalogs for fans to explore on streaming services. “They were fully formed propositions,” says Kraines. “I feel like a whole new generation found their new favorite artist and their new favorite song, and they’re digging in on that.”

Chart longevity may also be a product of post-pandemic timing, says Michael Martin, SVP of programming at Audacy. After all, before “Lose Control” logged 92 weeks on the chart, The Weeknd’s “Blinding Lights” and Glass Animals’ “Heat Waves” were quarantine-era anthems that previously set the record in April 2021 and October 2022, respectively.

The fact that the record has been reset three times in the past five years nods to how the lifespan of a mega-hit changed to account for audience appetites. “Everybody wanted comfort food, right?” says Martin of pandemic-era pop. “People wanted things they knew, like their favorite TV show that they binge-watched again. There’s something about that familiar song that they loved and wanted to keep hearing.”

Yet Kraines points out that the key difference between the music industry of five years ago and the industry today is how viral hits are located and promoted by labels to set up longer chart runs. At the dawn of the TikTok era, unknown artists with a viral spark were quickly signed and pushed to radio programmers and streaming services; now, artists like Swims (who was signed to Warner Records in late 2019 after some YouTube covers made noise) are often developed for years before a single receives mainstream promotion.

“We’re seeing that the whole nature of artist development takes time,” says Kraines. “And songs that maybe don’t come out of the gate super hot are definitely growing.” Case in point: “Lose Control” debuted at No. 99 on the Hot 100, then spent a record 32 weeks climbing to the top of the chart. “People are taking more time to sit with music and enjoy it — they’re not just one-and-done,” adds Kraines.

Meanwhile, the streaming era has included less distinction between singles being actively promoted by artists and album cuts that have no shot at extended chart runs. Last year, Billie Eilish launched her Hit Me Hard and Soft era with “Lunch” as the focus track, but quickly pivoted when fans embraced “Birds of a Feather” on streaming services. Demand for “Feather” has remained strong across platforms since its release — so radio programmers kept playing it, streaming services kept it high on their flagship playlists, and the song just crossed the one-year mark on the Hot 100.

One key to that type of extended run, says Tear, is the smart deployment of follow-up singles — songs from a popular artist that prevent listeners from getting tired of their mega-hit, but don’t necessarily get in its way, either. A generation ago, radio stations couldn’t feature multiple songs by the same artist in heavy rotation, but now that streaming has blurred those lines, programmers can balance a handful of songs by the same artist and ultimately extend the life of a smash.

“The audience wants to hear more than one song being played over and over again,” Tear explains. “I’m now able to go two, three, four songs deep [per artist], like we do with Sabrina Carpenter, Benson Boone and Teddy Swims. That relieves a little bit of the fatigue, and they stay around longer.”

Paradoxically, the fragmentation of popular music — and how the streaming era has affected the number of songs that reach cultural ubiquity — may be the reason why we now have so many smash hits that stick around forever. Veteran radio programmer and consultant Guy Zapoleon has spent his career chronicling 10-year music cycles of popular radio, and says that modern “lack of consensus” caused by the proliferation of music platforms means that, when a song does become huge, it stays huge for longer.

“Because there’s so many different sources to go to, it’s difficult for songs outside the very biggest songs to become hits,” says Zapoleon. “And because of that, those songs take a while to become hits, and then they stay there for the longest period of time — longer than we’ve ever seen in the history of music.”

The good news is that this industry era of extended chart runs emphasizes hit songs regardless of who they’re coming from. While A-listers like Kendrick Lamar, SZA and Morgan Wallen have topped the Hot 100 in recent months, the top 10 has been rife with new artists scoring their first chart hits in 2025, just as it was last year.

“You can keep delivering listeners songs like ‘Lose Control’ that they’re just not tired of, but you can also deliver the new artists that they’re asking about — Doechii, Sombr, Alex Warren, Lola Young, Ravyn Lenae,” Martin points out. “So I don’t think there’s stagnation in new product, or in new artists.”

A English hard rock band that performs in masks and cloaks is not the type of artist that regularly visits the top of the Billboard 200 — yet anyone who had been paying attention to Sleep Token’s rise over the past few months knew that their fourth studio album, Even in Arcadia, was going to have a strong debut.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

After years of building a fan base, expanding their lore and inching onto the Billboard charts with increasingly higher peaks, the group kicked off the year by scoring their first career Hot 100 entries, as well as quickly selling out a slew of fall arena dates. When Even in Arcadia was released on May 9, its album tracks flooded streaming charts, a clear sign that the early enthusiasm around the album had coalesced upon its release.

Yet when the dust settled on its debut week, even the most bullish Sleep Token fan had to be pleasantly surprised: Even in Arcadia debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 chart dated May 24 with 127,000 equivalent album units, according to Luminate — good enough to not only score Sleep Token’s biggest chart week ever, but the biggest total for a hard rock album in nearly two years, as well as the largest streaming week ever for a hard rock album. It’s the type of debut that blows away even the most hyped-up prognostications, and immediately makes Sleep Token one of the biggest stories in rock this year.

Trending on Billboard

The performance of this album cycle has “by far” surpassed expectations, RCA Records COO John Fleckenstein tells Billboard. Sleep Token — which debuted nearly a decade ago and has always remained under cover of anonymity, with band members never revealing their identities or speaking to the press — signed with RCA in early 2024 following the release of third album Take Me Back to Eden. That album became the band’s first to hit the Billboard 200, debuting at No. 16 in May 2023, and produced some of its first songs to hit the Hot Rock & Alternative Songs chart.

Yet when “Emergence” — the six-and-a-half minute, multi-part prog-metal epic that opened the Arcadia era in March — debuted at No. 57 on the Hot 100 in March, thanks in part to some mind-boggling streaming numbers (9.9 million official U.S. streams from March 14-20, according to Luminate), RCA had to adjust its forecast for the commercial prospects for its host album, says Fleckenstein.

“We knew they were great, and they were potent,” he says. “But when ‘Emergence’ came out, that’s when we saw the reality of where the numbers had gotten to.”

“Emergence” was followed by “Caramel” — a more radio-friendly (yet no less audacious) single that somehow pulls off a fusion of rhythmic pop, shuffling reggaeton and a shrieking metal breakdown — and “Damocles,” Sleep Token’s version of a power ballad with twinkling pianos that morph into thundering guitars. Both of those songs hit the Hot 100 as well, at Nos. 34 and 47, respectively — and the fact that the second and third songs released from Even in Arcadia peaked higher than the first on the Hot 100 indicated to RCA that the host album was going to be a monster.

“Everyday along the path into this album, we were more and more confident that this was a big deal,” says Fleckenstein. “We just don’t see that kind of fan behavior and consistency, in terms of new music coming out.”

When RCA signed Sleep Token last year, Fleckenstein says that the two biggest indicators of the band’s upward trajectory were its rapid growth as a live act — the group leapt from clubs to theaters, and now to arenas, with strong ticket demand for each live run — and the online dedication of its fan base. The London natives have crafted a complex backstory over the year, with Sleep Token leader Vessel speaking of a higher power called Sleep and causing fans to parse through lyrics and messages to unlock new mysteries from their world.

For the band’s new major-label partner, Sleep Token’s anonymity has felt “liberating” as a promotional tool, says Fleckenstein, particularly in an era of artists oversharing on social media platforms. “So much of it is about the art that the band makes,” he notes. “The world that’s being created is being driven by the fans, and as we were building [the rollout] with the band, the part that was so rewarding was that we could not get more clever than this fan base.”

Case in point: in February, before the album cycle had truly started, the band launched a teaser site full of jumbled numbers and letters, which fans quickly found out related to the geographic coordinates of an 18th century monument in England. “It all happened in a blink!” Fleckenstein says with a laugh. “It’s because you’ve got a fan base that is undyingly passionate about this band.”

Now that Even in Arcadia is here, fans’ attention will now turn to how the album will be presented live: Sleep Token will perform the new material for the first time next month at a handful of European festivals before their U.S. arena tour kicks off on Sept. 16. In the meantime, the noise of this album debut has already unlocked opportunities for Sleep Token that aren’t normally reserved for hard rock acts: Vessel was featured as the main image of Spotify’s New Music Friday playlist on release day, for instance, and all 10 of the album’s tracks have made the Hot 100 chart. Combined with Ghost’s new album Skeletá debuting atop the Billboard 200 two weeks prior to Arcadia, a brand of new-school hard rock with baked-in mystique and accessible hooks is experiencing a mainstream boom that’s been years in the making.

“The numbers here are basically in line with high-caliber pop artists, in terms of consumption level,” says Fleckenstein of Sleep Token. “Up until this point, the focus has been on the fan base, and that won’t change — they’re the reason why we’re here… But in a lot of ways, the story from here will probably be that this isn’t some niche thing. There’s definitely a broader awakening here among media and partners that are looking at this in a different kind of way.”

A similar effect is trickling down to pop fans, too. “There are people that haven’t discovered this band yet, because they haven’t been part of the lore and they perceive it as metal, which may not be their genre of choice,” Fleckenstein says. “But it’s great music. And I think that’s going to be the road ahead.”

Indie rock shows are often the province of, as LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy said in the band’s “Tonite,” “the hobbled veteran of the disc shop inquisition” — the graying, largely male species of armchair critics who listen to Sirius XMU and love to lord their music discoveries over those less informed. Not so with Car Seat Headrest: The Seattle-based band’s concerts attract a fascinating cross-section of fans. Yes, the geezers are there, but so are the moshers, frat bros, furries, and — lending hope to the future of rock’n’roll — millennials, Gen Z and even a smattering of Gen Alpha teens letting their freak flags fly.

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Car Seat Headrest’s music speaks to this multitude of generations in part because, musically, they have synthesized their many individual influences — past and present — into a sui generis sound. The band’s leader and primary lyric-writer, Will Toledo, grew up listening to his parents’ folk and country albums, as well as classic rock, r&b and soul. CSH’s guitar genius Ethan Ives lately has been listening to Beethoven, Pentagram and King Crimson. As a unit, the quartet, rounded out by drummer Andrew Katz and bassist Seth Dalby,’ have played and toured together for the last 10 years or so — circa the release of 2016’s breakthrough album, Teens of Denial, and in this time they have achieved a virtuosity that stands out among their peers.

Trending on Billboard

Lyrically, Toledo has largely avoided pop and rock tropes, like romantic love, sex and heartbreak (although drugs often figure into his songs). He prefers to gouge deeper into tough, unsolvable existential topics: alienation, familial relationships and the melancholia that comes with growing up in the digital miasma of the 21st century.

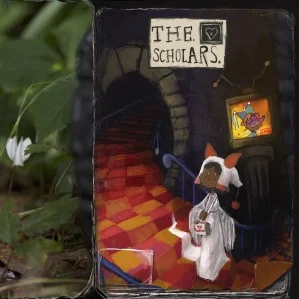

These outsized talents and a sizable amount of ambition — long a CSH trait — all come together impressively on the band’s first fully collaborative album, The Scholars, a rock opera that is destined to stand with landmark recordings from previous decades: The Who‘s Quadrophenia (1973), Pink Floyd‘s The Wall (1979); Drive-By Truckers‘ Southern Rock Opera (2001) and Green Day‘s American Idiot (2004).

The Scholars, which Matador will release on May 2, stands apart from those other epic recordings in that it is more of an existential exploration than a strictly conceptual one. It’s a musically rich story propelled by a succession of characters — some who interact and some who don’t. (Ives compares it to Paul Thomas Anderson’s 1999 film, Magnolia.) The album is set in and around the fictional Parnassus University, populated by numerous characters — Beolco, Devereaux, Artemis and Rosa, among them — and narrated by The Chanticleer, a Greek symbol of courage and grandeur, and in Old French translates to “to sing clearly.” The antique-sounding names and places seem to be a conceit to show that past is prologue. Even when songs allude to cancel culture (“Equals”) and societal and environmental decay (“Planet Desperation”), these are not new problems. They’re just disseminated now by social media, not a Greek chorus. It’s the kind of album that will resonate with young folks forced to move back in with their parents because of the economy and the parents who are housing them.

The Scholars requires a certain amount of commitment. Three of the songs, “Gethsemane,” “Reality” and “Planet Desperation” break the 10-minute mark, with the last of the three clocking in at 18:53. And yet, the lion’s share of the songs come with sticky hooks that build and progress in a way that belies their length. “Gethsemane,” which approaches 11 minutes in length, is even getting a good amount of play on Sirius XMU, and the album’s pinnacle, “Reality,” in which Ives and Toledo share vocals — they liken it to Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb” — could easily go on beyond its 11:14 run time.

Dalby, Ives, Katz and Toledo came together on Zoom to discuss the making of The Scholars, the ideas behind the music and lyrics, their upcoming tour and their side projects. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Sonically, The Scholars reminds me a bit of David Bowie’s Blackstar in that there’s such a symbiotic feeling to the music. You feel that you’re inside it. How did you guys achieve that?

Will Toledo: I don’t recall everything about the Blackstar sessions, but I feel like they probably worked and jammed together. I think the musicians he recruited were already kind of a unit, and they were used to improvising together and collaborating. You have that symbiosis, because that freeform mesh was already there.

For us, some of the material came out of solo demos from me and Ethan and everybody else, but a lot of it resulted from us just jamming in the studio together. We’ve had ten years of being a band, and mostly our opportunities for jamming were limited to soundcheck when we were not ready to soundcheck or practices when we were not ready to practice. This was the first opportunity where we would go in and spend a whole practice session just jamming. We really wanted to get loose with one another, fall into comfortable patterns and just go wherever the music was taking us. That resulted in an interchange — a more distinct weaving together of our voices. Whereas past records were more about solo material brought in to be played by the band.

Ethan Ives: We have a lot of musical influences in common, but we also each listen to our own individual styles of music. On this album, what you’re hearing is that we had a directive for each song. It was okay, this song needs to go to this place or touch on this theme. Part of the process this time was about throwing that to the room and then playing the flavors of music that we’re [each] familiar with to build out the song. So, maybe there was more of a deeper well of stuff getting pulled on in this one.

Toledo: What I see in myself and how I play into the band — I’m very sensitive to sensory experiences and social experiences and I do tend to automatically hone in on, here’s the part I like. That kind of comes naturally to me. I’m always picking up stuff as I go, and thinking, “This doesn’t make me so comfortable.” Or, “Ooh, I want to change that more.” What I’ve had to work on more is patience and not judging stuff right away. Because especially in a jam you want to let stuff build organically. Really, for this record I was just trying to come in and listen to how the other three were intersecting, and just as far as what I was playing, push that and weave that together. I feel like my strength is more as an arranger than as a sort of composer from nothing.

Will, are the lyric credits all yours?

Toledo: Most of them. Pretty much anything that Ethan sings lead on he wrote, and for songwriting credits we just do a four-man split — that was what we agreed on going in, because of the way that we were creating this music. For most of the songs, I would take them home and write lyrics, especially for pieces that Ethan had come to the band with. He was developing the lyrics there as well.

Before Making a Door Less Open, a lot of your songs sounded like they could be pieces of a rock opera. Is this something you’ve had in mind for a long time?

Toledo: Growing up with records like Dark Side of the Moon and Pink Floyd in general and The Who, I was always aware of the possibility of a concept album or a rock opera. I always shied away from the idea of doing it because it’s a pretty daunting concept and I didn’t want to sacrifice the song-by-song quality of things to make some sort of narrative. After Making a Door Less Open, though, that was an approach where each song was really its own world, and the record came out a little disjointed because of that. You have to magnify with a microscope each one of those songs to appreciate it. That’s an interesting approach, but I wanted a more cohesive flow to an album.

So, I felt more inclined to go in the opposite direction. I landed on a midway approach, where we weren’t going to force a narrative, but have this idea where each song is a character. That way, we can still preserve the integrity of each song and feel good about the ones we put on the album. But then there’s that inherent narrative quality that comes when you’re seeing each character come out on stage.

Car Seat Headrest

Courtesy Photo

How would you synopsize The Scholars?

Ives: Part of what I feel a sense of accomplishment about and what I feel is successful about the album is that it’s my favorite type of conceptual record as a listener. Which is that the narrative is not so rigid that it has an authorial narrative interpretation. Pink Floyd’s The Wall has a very specific meaning. That’s not a weakness, but it is a very particular style of concept. I tend more towards albums that have conceptual threads but are more interpretable or more based on abstractions. We probably all will have a different version of what we think the album represents, but I think of it as tracking the lives of a bunch of different characters to amalgamate a greater life/death/rebirth cycle. It’s a cycle that could be seen as one person’s life, but it’s really a series of different story beats made from moments in different people’s lives, in a Magnolia sort of way.

Toledo: My interpretation wouldn’t be too different. Like Ethan, I prefer concept albums that aren’t so rigid that it has to be this plot. I was hoping for a record where you could put it on and not know that it was a concept album, or that there were these characters or this backstory, and still have a full experience. We wanted the music to speak for itself. As far as selling it to someone who needs a description, I would say it’s about weaving together the past and the present and having these young characters — who maybe don’t know a lot about the past and have problems that are more specific to our times — walking through these patterns that are quite ancient or timeless. I was pulling a lot from folk song tradition in crafting these characters and their struggles. In folk songs, you can see what people have been talking about for centuries and centuries and what really has sticking power.

Seth Dalby: I think Ethan and Will definitely have a more concrete idea of where each character lives and what their struggles are. For me it’s just a place to get lost. The setting is obviously like a fantasy school, and then your imagination goes wild with these characters.

Andrew Katz: You’re scraping the bottom of the barrel now for these answers. I’m not a guy that listens to lyrics. I listen to syllables and music. Asking me what an album means — you’re asking the wrong guy.

Toledo (to Katz): What would you say to yourself, if you had never heard this record, to say you should listen to it?

Katz: I would say it sounds epic. I go off of feel and how the words roll off the tongue. Even when I’m listening to songs by System of the Down, for example. They do a great job of just making s–t sound cool. I have no idea what any of those songs mean — what they’re supposed to be about. They just sound cool. I would say our album achieved that, too. It’s epic.

Will, you told Rolling Stone that The Scholars was an “exercise in empathy.” When I listen to the album, I hear a search for identity that comes with extreme sadness and pain. Does that sound right?

Toledo: Yeah, absolutely. One of the early concepts that I was working off is — it’s all these different characters, but it is also on a more spiritual level, one character and their progression through life, and even life and death. But maybe the life and death of an identity. I see this shaking off of the old and reaching towards the new, and there’s a lot of darkness and pain that comes along with that. You have to walk into the darkness to find out more about who you are. I kind of see each song as a step along that way.

Will, when the band performed the album at the Bitter End in February, you dedicated the song “Reality” to Brian Wilson. You called him “a prophet who lives in the darkness.” Ethan, you read a note about what you described as a generational divide. It sounded like you were talking about the Boomers and Gen X, but you all are millennials. Could you both elaborate?

Ives: Those things got all jumbled up for me in my upbringing because my parents were so deeply hippie that I feel like I skip a generation. I don’t want to give the impression that the whole song is purely about complaining about Boomers, but it’s a song that I picture as the main thrust of the character who wakes up one day and is like, “How did I get here? Why am I here? Why is this happening to me?” And then tries to trace back the chain of events that led things to turn out this way. And maybe there’s some regret and some reproach for other people or for an earlier version of yourself.

Will and I each wrote our respective lyric segments in that song, and I always thought of it as a “Comfortably Numb” vibe, where one singer takes one narrative point of view, and one takes another. We’re coming at the song from two different angles and meet in the middle where the emotional core of the character that I just described fits really well with the figures that Will was referencing in the lyrics. Artists like Syd Barrett or Brian Wilson, who experienced so much brilliance in their lives and then probably at some point just woke up late one morning and were like, “What happened to me?”

Toledo: Like Ethan said, we wrote our own parts coming at it from different perspectives. With the line, “We still sang songs and made merry, but deep down we knew something was wrong,” I got the sense that my voice would be as the Chanticleer character. So, when Ethan is singing, you have the voice of those people expressing this dissatisfaction and the feeling of, where did we go wrong. The Chanticleer character became for me this artist figure who has chosen to elevate the struggles of the people and, as artists sometimes do, chase the spotlight. The burden that comes with that is you have to dig into the hearts of people and find a deeper truth. I have these two choruses where they’re coming to the Chanticleer and saying it’s not enough. We need more color. We need more life. Then in the second chorus it’s too much. We can’t take it anymore.

The role of the artist —especially that Syd Barrett/Brian Wilson type — is a bit of a toxic one, because culture really elevates those who fly very close to the sun and get burnt. It lets them suffer for the sake of being that preacher. I have a conflicted relationship with it, because I loved these artists and the idea of that kind of artist when I was a kid. And I played my part in elevating that idea of artistry. Now I try to find other models that are more stable. But there is a basic truth where, if you want to dig and try to speak those deeper truths, you do get burned.

Your parents were in the audience at The Bitter End. A lot of Car Seat’s music — I’m thinking of “There Must Be More Than Blood” and on this album, “Lady Gay Approximately” — have parental or familial themes.

Toledo: Yeah, on this record specifically, but even beyond that when it comes to writing about love, I’m just not that interested in writing about romantic love and partner love. That is really almost the only type of love that you hear when you think about a pop song. I look towards other traditions, and especially in country and gospel tradition, there’s a lot more of singing about parent-child relationships. That seemed like a more meaningful thing to me to write about.

“Lady Gay Approximately” is based on a folk song called Lady Gay which is about a mother and her children. I was also looking towards the bible for inspiration and in Genesis, a lot of content is about parents and children; fathers and sons; mothers and sons. This model of love is the one that we know throughout all our lives. So, it seems like it’s more relevant and important to write about. And that became a focal point of this record.

Do you guys have any thoughts of staging this as a rock opera? I don’t know if any of you saw Illinoise, the dance musical built around Sufjan Stevens’ music. Also, I could see this being made into a movie like the animated film Flow. Given the love that the furry culture has for you, I could see the director of that film [Gints Zilbalodis] doing something fantastic with the album.

Katz: Hey, if the director of Flow wants to make a movie about our album, yeah, for sure. That would be great.

Toledo: I’m usually the brake presser as far as opportunities, because there are plenty of things that we can do, and it’s more of a question of, “What do we want to take on this year? How many things can we take on before things start splitting off?”

Right now, we’re happy and we’re busy. We’re practicing for our show, and we are going to be playing this record live, but it’s just going to be the band and some lights. There’s not going to be any elaborate staging beyond that. We figure the music speaks for itself. We would rather have something simple where we can really feel like we’re comfortable onstage. With [Making A Door Less Open], we upped the theatrics, we upped the costumery, and it was kind of a drag. There was a lot to worry about every night — a lot that can go wrong. We all prefer to keep it as simple as possible on our end and give it a better chance of being good and replicable every night.

Beyond that, we’ve got a Patreon. Every month, we’re putting out content there. I’m trying to write two new songs every month and put them out. As far as more content for Scholars, more adaptations of it, as Andrew said the right offer might come along and then we’d consider it. But as far as actively pursuing it, we’re happy with the workload we’ve got at the moment. I would say, “Let people sit with the album, come up with their own images of it — and if something else comes out of it, let it be organic.”

Are you going to play the whole album on the tour?

Toledo: It will be more or less the whole album. We might skip a song or two, but the idea is to keep that flow. Practicing for the Bitter End and earlier, we all just agreed that this album has a good flow from start to finish. It feels good as an album and it feels good as a show.

When I go to your shows, I just see so many different types and ages of people. Why do you think you appeal to such a wide array of music lovers?

Toledo: That’s one thing that’s always really pleased me about our live shows. There’s always a big mix. I think it started out with the way that I approach music. I didn’t grow up enjoying modern pop music. I trended heavily towards what my parents were listening to — so ‘60s music, older country and folk music. That gave me a backbone musically that differentiated the early Car Seat Headrest music from what other people were doing. It was a little more isolated, and I think, because of that, it took several years before it started to find an audience. Younger people connected with the emotional content, which was as a young person writing lyrics and content. I was expressing stuff that they could relate to as well.

And then, as we became a band, rather than homogenize and do something that appealed to one audience, we were all bringing different stuff to the table. We’ve always just had that approach of: cast a wide net, see what the overlap is, see what we can all agree on. And then that diversity of opinion and approach creates music that resonated with a lot of different people.

Most you have released side projects. Ethan, is there a new Toy Bastard album in the works?

Ives: There’s one that came out last summer, The War, that I’m still repping to people. I worked really hard on it and was very pleased with it. I worked with Jack Endino [Pacific Northwest producer of Nirvana, Soundgarden, L7] a little bit. He engineered a portion of the tracks, and he was fantastic. You can tell the songs that he engineered because they have a special flavor that only he can bring.

Katz: I’m working on a new 1 Trait Danger album. Who knows when it will be out? I’ve got nine songs done, but I’ve got to meet with Will when he’s ready and get him to orchestrate the story. Will’s job is to create the narrative with the crazy songs that I make.

Dalby: I don’t know if mine is ever going to be out, but it will be finished at some point.

Ives: I feel like you’ll finish it and then just put it on a hard drive and lock it away.

Katz: No one is ever hearing that music.

What are you guys listening, reading or watching right now that moves you?

Ives: I’ve been listening to a lot more classical music. A lot of the late Beethoven string quartets but then mixing them up with listening to a lot of Pentagram and King Crimson.

Toledo: I’ve been a little scarce on consuming music. I just realized that my life was kind of surrounded by movies and TV and music. Lately I’ve been trying to just cut back and enjoy silence and whatever sounds are in the sphere that I’m in. And just talking to people really. I mainly listen to our own music because we go in and practice it. Or writing and practicing the new material and putting it out on Patreon.

Do you guys ever talk in terms of a five-year plan?

Katz: No, but I like where your head is at. I see myself in a huge mansion on the water. It’s a pipe dream, but that’s where I see myself.

Ives: I feel like we have our version of that, and then the way that music and the music industry works, we always end up having a completely different thought about it 12 months later.

Toledo: For us, five years is baically an album cycle — so where we’re at in the cycle is where we’re at in the five-year plan. We don’t discuss it that often, because it is what it is. Right now, we’re basically on the final year of the Scholars cycle — maybe another two years — but it’s more about seeing where we’re at and what work we’ve got to get done.

Ray Vaughn has arrived at New York’s Billboard office for the second time in just over a week. He previously popped in and played a few tracks off his first official release with TDE, The Good The Bad The Dollar Menu, before flying out to continue his first-ever project rollout.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

As Vaughn settles in the second time around, his voice is gruff, worn from rapping, recording, interviewing, and flat-out existing. Regardless of the physical wear-and-tear, he’s chatty, in high spirits, and devoid of exhaustion. When asked if he’s feeling winded at all, he says with a laugh, “I don’t wanna go back to that f—in’ car.”

The Good The Bad The Dollar Menu is a product of years of strenuous grinding. Born in Long Beach, California, Vaughn was raised by a family of local rappers; he says his uncle nearly signed a deal with DMX before he “crashed the f—k out,” and his mother went by the rap moniker Sassy Black, hosting “Freestyle Friday” sessions at their house for friends and family.

Trending on Billboard

Vaughn’s earliest indicator that rap could be in his future came to him during those sessions in his living room. When he’d spit, people would listen. He locked in to rapping almost immediately, and at 15, Vaughn’s reputation had made the rounds in his community. A few labels even came calling, including Def Jam.

“My mom kept blowing meetings,” Vaughn says. “She just kept being like, ‘Oh, you’ll go next time.’ We was already so thorough, she didn’t even know. We was already robbing houses, shooting at people, we was doing s—t that could have got us real f—kin sentences. I was moreso like, ‘Let me go!’”

His mom had fallen down the rabbit hole of early YouTube conspiracy theories, believing the Illuminati had infiltrated major labels like Def Jam. No matter how hard he pushed, she always said no. After one particular nasty fight, she threw Vaughn out and he turned to the streets to make ends meet while still clutching onto his rap dreams.

Success trickled in and out of Vaughn’s life: he went viral a few times for various freestyles, but they didn’t lead to anything concrete. A promising moment came in 2019, when he ran into Ye’s cousin Ricky Anderson, who was managing G.O.O.D Music at the time, at a New Year’s Eve party. After Vaughn stealthily queued up his own songs to play at the party, Anderson suggested he meet with Ye face-to-face.

“He’s crazy, but he’s a genius,” Vaughn said of his meeting with Ye. The conversation went well, and Vaughn penned a few songs for Ye before arranging a meeting about a label deal. On the day of the meeting, however, Vaughn showed up to an empty room. He never spoke with Ye or the G.O.O.D. Music camp again.

“That same day I said to my manager, ‘Bro I’m still sleeping in my car, I don’t know what the f—k I’m doing!’” Vaughn recalled. His manager brought up an opportunity to record a song with an artist who was trying to get Jay Rock on as an additional feature. Two weeks later, Vaughn received a call from Top Dawg Entertainment CEO Anthony Tiffith.

“I hung up on him — I didn’t know what he sounded like, so I thought it was a joke,” Vaughn remembers. Tiffith called back, invited him to Interscope Records for a sitdown, and the rest was history.

After Vaughn’s first TDE project dropped on Friday (Apr. 25), the rapper spoke about it with Billboard.

Just to clarify, this is a mixtape and not an album.

Yes. I never wanted to call nothin’ an album if it wasn’t an album. I always was like, “With my first album, I wanna go crazy.” I’m very, very careful about calling something an album. That s—t counts. You could have 1,000 mixtapes and flop, but if you have an album and it flops? I know that’s something internally that’s gonna scratch my soul.

You don’t waste a bar on this mixtape. How did you approach writing for this project, and how do you approach writing in general?

Just make sure you keep it full of integrity. That’s the lost art form, period. Some records I don’t have bars on, it’s just a message, like ‘Pac. He didn’t have metaphors in every song. He was just very direct, and said what needed to be said, and you felt it.

I feel like nowadays we got so many people who punch in. It’s not even a cohesive thought. What is that verse about? What is this song about? Who are you talking to? Who is the audience? I still believe in that art form. If I rap this a cappella, does this s—t make sense? It’s like poetry. If you can’t say it a cappella and it [doesn’t] makes sense, it’s like rambling.

Now that you’re officially entering the game, how do you feel about your place in rap?

Once I turn into the star I’m supposed to be, where other people see the star that I am, the influence will come after. Like Kendrick [Lamar], the fact that he’s making music that slaps, but it’s still got some conscience to it. People wanna follow that because they’re like, “Oh, he’s talkin’ about something.”

Outside of the Drake and Kendrick situation, it does feel like mainstream rap is heading away from lyrics. What are your thoughts on the more party-oriented rap?

We need those type of artists too! It’s a talent in being succinct. [Starts singing]”Soulja Boy off in this oh, watch me crank it, watch me roll, watch me crank dat Soulja Boy, Then Superman dat oh.” That s—t is hard to make for people who actually write lyrics, and nobody wants to feel like they’re being preached to all the time.

When you were writing songs like “DOLLAR menu,” how did you toe that line, to make sure you weren’t being too preachy?

I feel like there’s a very thin line between being preachy and delivering a message with wittiness. I have to change lines sometimes. I’m just speaking from my experiences, mostly. This is me and how I look at it from my perspective. I don’t want people to put me in a box with Kendrick. When Cole made “Grippy” with Cash Cobain, people tried to cook him. If [Cole] had been somebody else, it’d be like, “Oh this song is hard.” The expectation for his lyrical content is set so high that if he dumbs it down too low, then they be like, “What the f—k are you doing?” So they don’t even get to have fun.

With that in mind, what are you hoping to communicate with The Good The Bad The Dollar Menu?

I’m just perfecting a pepperoni pizza before I say I have wings, salads and calzones. That is my pepperoni pizza.

On songs like “FLAT Shasta” and “Cemetery Lanterns,” how do you revisit such traumatic memories and not get bogged down by it? How do you make sure the resulting art is authentic?

I just tell it like it is — exactly like it is. I’m in a good space. I’m signed to a f—king label that’s at the f—king peak of their career. I got nothing to complain about right now. Reflecting? That’s easy.

There’s a lot of soul-baring on the project. Do you ever worry you’re revealing too much for a first mixtape?

There were songs we moved out of the way because they were too heavy. I don’t want to go too crazy, because I want people to actually listen, but I also want people to know that if you listen to it and feel something? You just witnessed the super power.

Shane Boose says that, if a piece of music can be described as “alternative” or “indie,” he’s probably going to enjoy it. “My favorite band of all time is Radiohead,” Boose, who records as Sombr, tells Billboard. “And I’m a big fan of Jeff Buckley, Phoebe Bridgers, The 1975. I listen to a ton of alternative music — it’s my genre.”

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

Those influences help explain why Sombr’s two fast-rising hit singles, “Back to Friends” and “Undressed,” have not only exploded on streaming services as crossover pop hits, but have also minted the 19-year-old singer-songwriter at rock and alternative platforms that have been starving for fresh new talent. On this week’s Hot 100, “Back to Friends” leaps up 14 spots to a new peak of No. 56, while “Undressed” jumps 12 spots to No. 84; meanwhile, “Back to Friends” hits the top 10 of the Hot Rock & Alternative Songs chart for the first time, bumping up to No. 9 with “Undressed” close behind at No. 13.

Sombr has been on the road over the past few weeks opening for Daniel Seavey in the U.S. — watching each day as his streaming totals grow (through Apr. 17, “Back to Friends” had earned 40.7 million official on-demand streams, while “Undressed” had earned 19.5 million streams, according to Luminate) and his crowd sizes swell.

Trending on Billboard

“They 100 percent break my brain,” he says of the streaming totals. As for the crowds, “You don’t usually get to see it happening in real time, increasing every show, but being able to see that has just put it into perspective. When I’ve had moments in previous years, they’ve never been like this. And I’ve never gotten to visualize it while it was happening in real time.”

Boose grew up on the Lower East Side and attended the prestigious LaGuardia High School, where he studied vocals while tinkering with GarageBand and Logic in his bedroom. “I made the first few songs in a more shoegaze vein, and most of those songs aren’t even out,” he says. “And then I made the song ‘Caroline’ after listening to Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago album, and I’d like to think that’s the first good song I ever made.”

Released in mid-2022, “Caroline” is indeed a sparse, wrenched folk song that Boose posted to TikTok before going to bed one night, and woke up the next morning to find thousands of reactions. He dropped out of high school, signed a deal with Warner Records in early 2023, then spent roughly two years trying to get lightning to strike for a second time with a string of singles, to little avail.

Sombr, who still writes and produces all of his songs, says that he never got impatient while awaiting his breakthrough following his major label signing. “I was just making music,” he says, “and I’m a really hard worker. I like to think that, if you really put in the hours and manifest what you want, it will happen.” On the day that he made “Back to Friends” in his bedroom, he played the finished chorus back, and felt that, with this song, it was finally going to happen for him.

Released last December, “Back to Friends” is a swirl of shakers, dramatic piano chords, fuzzed-out vocals full of post-hookup anxieties and harmonies that lob out rhetorical questions on the chorus. Along with March’s “Undressed,” a ghostly warble-along with an equally outsized chorus, Sombr has reinvented his sound over the course of two songs, moving on from the hushed singles released post-“Caroline” and toward slick, slightly swaggering alt-pop.

“I think they gave me a platform to make more upbeat music,” he says of the two tracks. “Before ‘Back to Friends,’ all my music was very ballad-y — there was nothing with a beat. I was so tired of that. I feel like this is a lot more free, as far as the music I want to create. And I wanted my show to be more exciting. I didn’t want to just do ballads forever.”

After wrapping up his tour with Seavey last week, Sombr will next hit the road with Nessa Barrett, joining for a month-long European run that kicks off on May 26 in Dublin. Earlier this week, however, Sombr announced a fall headlining tour across North America that will start on Sept. 30 — and thanks to the surging momentum from “Back to Friends” and “Undressed,” pre-sale tickets apparently sold out within seconds. (“The response has been insane,” Sombr posted on Instagram. “I hear you all. I am working on upgrades and new dates. Stay posted.”)

And while Sombr says that a proper debut album is “definitely on the horizon,” he’s trying to savor this singular moment. “The last show in New York, it was the loudest it’s ever been, and I got it in the pit,” he says before letting out a quick laugh. “It’s getting wild, and I love it. It’s all I’ve ever wanted.”

Wiz Khalifa delivered.

15 years after he dropped his classic Blog Era mixtape Kush & Orange Juice, the multi-platinum rapper decided to go back to his roots on its sequel tape and tap back into the sound that made him one of stoner rap’s most important rappers. He also brought the gang back together as Cardo, Sledgren and his stoner-in-crime Curren$y all contributed like they did during that first cypher back in April of 2010.

Kush & Orange Juice 2 also features the likes of Gunna, Mike WiLL Made-It, Ty Dolla $ign, Don Toliver, Larry June, Conductor Williams, and legends in Juicy J, DJ Quik, and Max B, among others. And while those acts are diverse in terms of their own individual sounds, Wiz was able to have them fit the story he wanted to tell and he did a pretty good job. It’s rare if not damn near impossible for a sequel to be as good as a classic, but Wiz did a pretty good job. Clocking in at 23 tracks and 77 minutes long, the Kush & OJ sequel is the perfect soundtrack for that cousin walk on Easter Sunday — as you and your family celebrate not only the resurrection, but 4/20 as well.

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news

And as he rolled out the much anticipated project, Khalifa went on an already-memorable run of freestyles that started last November with “First YN Freestyle.” Hopefully more rappers will hop on that wave, and give fans more music that feels fun and low-stakes.

Trending on Billboard

Billboard talked with Wiz about why he decided to take that approach, and about a bunch of other things. Check out our chat below and be sure to go run up that Kush + Orange Juice 2 this weekend.

You’ve been on a crazy run lately with these freestyles. Can you talk about why you decided to go that route?

Really just by seeing the reaction of my fans and the people who support me when I started to get into the mode of promoting Kush & Orange Juice 2, and really visualizing what that was going to feel like for everybody else. I wanted to make it an experience, and not something that just dropped overnight and then went away. So, me doing the freestyles was kind of a way to write that narrative and to get everybody on board so they understand what to expect and it got a great reaction. So, naturally, I just kept going. And it’s something that I like to do just for fun.

Did the freestyles help spark something creatively in you?

I was already pretty much done with the album by the time I did the freestyles. But I think anytime I’m able to just play around and see what people enjoy, it gives me a sense of what to do next or what to continue doing. So, it definitely served its purpose when it comes to that.

You and other Blog Era peers like J. Cole, Kendrick Lamar and Drake have crossed over into the mainstream. So, now that you’ve achieved a certain level of success, does that mean that you plan on still playing the major-label game, or are you gonna go back to just making what you feel like making?

I think it all just kind of comes together, and it’s really about the fans and what they want and what people are are tuning into, and just me knowing that people digest my music for the way that I do it. It allows me to be free, but it also opens up a lot of different opportunities for me to put that in other places. So, it’s a beginning of a wave that could, you know, go on for however long.

Why do you think rappers have moved away from doing freestyles and stuff like that?

I think because clearances and a lot of people want their their stuff on the biggest platform. It’s hard to monetize a freestyle and if you put a lot of energy into it, a lot of people want it to go far, so that value has been missing. It takes certain artists to push it and to show that the value of it isn’t gone. It’s not really where you’re aiming to put these at. The people and the listeners, and their ears are there, and they’re going to discover it. I think people have to re-understand that and reimagine that.

So much has changed since you came in the game. If you were an up and coming rapper today, how would you approach your career?

I would approach it the same way. A lot of the younger artists or personalities, they know who their fan base is. They know who they’re talking to, and they reach out to them, and that’s what dictates what they do or what their next moves are. And a lot of artists are afraid of that, but there’s a lot of power and a lot of value in knowing who your consumers are and the people who want the best from you and aiming what you do towards them. And that would be my advice, or that would be what I would do. That’s what I’m doing now, is just focusing on the people who I know support and are expecting this, and really just making the experience for them.

One person that’s carving out a unique lane for themselves is streamer and producer PlaqueBoyMax. You were on his stream recently. How was that experience?

Yeah, it was cool working with Max, and that was the first time I had made a song live on somebody else’s stream. And even just with that platform of him being, you know, with FaZe and them having the reach that they do. That’s a whole different fanbase than the people who are used to me, and it was good to be able to win those people over, show them what my talent actually is, and work with somebody for the first time and create something in front of everybody that’s just super fun and super cool to me.

You floated the idea of doing a full tape with him towards the end. Do you think that can happen down the line?

I wanted to do it, but I feel like he’s already doing it, and he’s doing it in his way, where he’ll benefit off of it, which is cool with me. I’m always down anytime. If he needs me, then he’ll hit me.

What can fans expect from Kush & Orange Juice 2?

They can expect good smokin’ music, good chillin’ music, good motivational music, and good ridin’ around with the homies music. It’s definitely for the people who understand it. And it’s not just about the music, it’s about the experiences that you have with it. So, the more you listen to it and live with it, or even if it’s your first time, when you listen to it and live with it, it’s gonna change a lot. I’m really happy with that. I’m really confident in that, and I’m just really excited for everybody to experience that.

Are you performing anywhere on 4/20?

Yeah, I’m gonna be performing at Red Rocks in Colorado.

I interviewed Curren$y a couple months ago, and I had asked him if he has any 420 rituals and he said he doesn’t really have any because he’s always working. I’m assuming that’s the same for you.

Yeah, pretty much, especially at this point. A lot of people come out and visit us on those days, even if it’s family from the East Coast or an artist or whatever. They usually want to come kick it with us, so that’s usually fun. I get to see a lot of people who I just really enjoy smoking with, like Berner. It is work, but for me personally, I try to roll at least an abnormally big joint or two, and I usually smoke more dabs that day than I normally do as well.

I wanted to ask you what your favorite strains were, but on Club Shay Shay, you said you’ve been smoking your own strain exclusively for about 10 years now.

Oh yeah, it’s definitely Khalifa Kush always for like almost 12 now.

What is that like, though — having your own strain and not really having to pay for it anymore?

It’s a blessing. I don’t know if I necessarily knew that it was going to be this way. We always hoped and wished that it would be this way — and knew that it was, you know, beneficial for everybody — but to actually live in an era where we can do this… It’s awesome. I’m grateful and I’m taking full advantage.

You also mentioned the Smoke Olympics. What would be some of the events if you were to put that together?

There would be a rolling competition. I’m bringing the origami, I’m bringing the samurai skills. What else? You have to hit, like, a bong. You’ll have to make a bong out of something. You could choose what you have to make a bong out of. You have to last a certain amount of rounds, too — so as we keep smoking, there’s no tapping out. Yeah, we’ll start there.

I ran into Conductor Williams recently and he was beaming about the way you approached “Billionaires” with Ty Dolla $ign. What was it about that particular beat that caught your attention out of the pack of beats that he sent?

I appreciate it. I feel like I always gravitated towards his production because of how soulful it is and just how musically inclined he is. You could tell he knows a lot about music in general. My approach is very specific to what I know my people are gonna f—k with. And I think when I got into that pocket, it was nostalgic, but it was also something that people never expected, or ever knew that they would enjoy.

I think that combination right there kind of makes discovering some new music worth it — and that’s what people need now, and to be able to do that with people who I’m cool with, and got in my phone and I can hit at whatever time, and be like, “Yo, send me some beats,” and we could just come up with something legendary off the bat. That’s real fun for me.

You’ve gotten into martial arts like over the years like Muay Thai and Jiu Jitsu. How important has that been for you?

It’s part of my everyday life as much as music is and I’m passionate about it the same way I am about my music, and I’ve been doing it for seven years now, and I feel like I’m still learning a lot of new things, and it’s still fun and it’s interesting. It’s not a chore or a job or I don’t even have a real end goal when it comes to it, so it’s fun to be on a journey and have something that I that I enjoy and that challenges me and also makes me better.

Has it helped your lungs be stronger too?

Yeah, 100 percent. My cardio is crazy, and it helped me learn how to control my breathing better and just being in good shape in general. Being able to function and and move athletically as I get older, because I’m 37 now, so I’m moving into my 40s. The older that we get the less athletic some of us get. But for me, it’s a lifetime thing of I’m always going to have this type of movement.

The Billboard staff’s list of the 100 best songs of 2005 highlights the macro-trends in modern rock from 20 years ago: veterans like Green Day and Foo Fighters were still scoring mega-hits, relative newcomers like The Killers and Coldplay were coming into their own, and bands like Fall Out Boy and My Chemical Romance were helping emo reach the masses. These bands headlined arenas, earned radio play and were constant fixtures on MTV. For a generation scouring a pre-smartphone Internet, however, there was an alternative to the rock bands that were already labeled “alternative.”

Explore

Explore

See latest videos, charts and news

See latest videos, charts and news