digital marketing

Trending on Billboard

From tour sponsorships to Taco Bell commercials featuring Turnstile, major companies see billion-dollar branding opportunities in partnering with artists, and a new study from Luminate has some matchmaking suggestions.

The industry-leading music analytics platform looked at five years’ worth of survey results and metrics measuring likability, awareness and brand endorsement to determine the best artists to market sodas, snack foods, cosmetics and credit cards. “Cultural capital isn’t something brands should tap into retroactively,” the report authors write. “Behavioral audience entertainment data can inform marketers, helping them to locate artists whose fan base matches a brand’s target audience. Think of it as ‘moneyball’ for brand partnerships.”

Related

Luminate has collected quarterly online survey results from a representative slice of U.S. consumers, ages 13 and up, since 2021. It identified super-purchasers of food & beverage, personal care & hygiene, travel, telecom, mobile apps and banking & finance products, and analyzed the survey results and other metrics to understand their attitudes and perceptions toward some 600 artists and 100 music genres and sub-genres.

The study deliberately stayed away from megastars like Taylor Swift and instead identified artists who may be less well known, but who among certain groups are well-liked and trusted, and therefore could provide brands with a better return on their marketing dollars, says Grant Gregory, a researcher and manager at Insights at Luminate.

“The decision-making process was a mix of identifying artists with high likability AND artists who are uniquely appealing (in terms of likability) or have uniquely high reach (in terms of awareness) among that category purchasing group vs. the general population,” says Gregory.

The artists who scored among the highest in each consumer category were: country crossover star Bailey Zimmerman for food and beverage products, the queen of regional Mexican music Ana Bárbara for personal care & hygiene products, rising country star Lainey Wilson for banking and finance, Bebe Rexha for telecom, Jamaican singer and rapper Shenseea for service and e-commerce apps such as ride hailing and food delivery and electronic artist Kenya Grace for travel.

Here are some of the highlights from the report.

Bailey Zimmerman

The study plotted the “Fall in Love” singer’s likability and brand endorsement scores from survey respondents who bought at least three packaged snacks, coffee or other food products recently. Zimmerman outscored JENNIE, Leon Thomas, Dolly Parton and Queen as a good bet for marketers. While Chris Stapleton had the highest awareness score, Zimmerman won on likability. His fans tend to be younger and more affluent than the overall population and are more likely to listen to music at least twice a week on Apple Music and Spotify.

“Zimmerman presents a narrower but deeper fandom among category buyers,” Luminate’s authors found, while “Stapleton offers a broader though still highly efficient fandom.”

Ana Bárbara

The longtime grupero singer/songwriter Bárbara beat Young Miko, Arya Starr and Dolly Parton when it came to her strength as a personal care product brand endorser, with only Parton beating her on likability. Bárbara scored particularly well in awareness, perhaps due to the current popularity of regional Mexican music. She over-indexes with Millennial, Gen X and even Gen Z consumers, and fan devotion is particularly strong. Those audiences are more likely than most to use social media apps, including TikTok and Instagram.

Lainey Wilson

Wilson falls in the middle of a pack of superstars that includes Stevie Nicks and Kelly Clarkson, who both rank slightly ahead of Wilson on awareness. However, Clarkson ranks high on awareness and public perception but in the average range for fan engagement metrics. Wilson ranked among the highest for likability and purchase likelihood.

Wilson’s fans also tend to have higher-than-average income, with 38% earning more than $75,000 a year, compared to the general population, and more than three-quarters of the banking and financial product consumers surveyed said they would be more likely to buy a product she endorsed, the report found.

Bebe Rexha

“Recognizable, out-of-the-limelight performers such as Bebe Rexha can still shine through in the data,” Luminate’s report found. The Brooklyn born “Meant To Be” singer has had four top 10 songs on the Billboard Hot 100, and her audience tends to skew young, with roughly two-thirds being from the Gen Z and Millennial generations. This audience is more likely than the general audience to use a streaming service like Amazon Prime Video, Netflix or HBO Max at least weekly, and 60% reported they would use a telecom product if she endorsed it. Among the general population, 42% said they would try a telecom product Rexha endorsed.

Shenseea

The Jamaican dancehall singer/rapper is among the best artists to market to a mobile app like Seamless, Uber or Airbnb, Luminate found. While Leon Thomas and Adele ranked slightly higher on likability scores among mobile app super-consumers — defined as people who use two or more mobile apps for services, such as food delivery or ride-hailing — 78% of those consumers who are aware of Shenseea said they would try an app if she endorsed it. That group tends to be more racially diverse, come from the Millennial and Gen X generations and they’re active across social media platforms, the report found.

Kenya Grace

The South African-born British electronic music singer Kenya Grace ranked is less well-known than Shenseea, Lola Young or Riley Green, but Luminate found that her U.S. audience looks a lot like the people travel companies want to target. Their annual incomes are more likely than most to be middle-to-high, with 61% making more than $50,000 annually, compared to less than half of the general population, and Grace’s audience frequently uses video streaming services like Disney+ or YouTube –appealing places for travel companies to advertise.

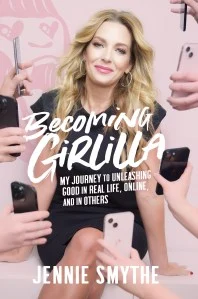

By the time Nashville-based digital marketer Jennie Smythe launched her company Girlilla Marketing in 2008, she had already gained significant experience working in marketing and promotion for companies including Hollywood Records, Yahoo Music, and Elektra. She also forged her path in digital marketing as the music industry was undergoing the profound transition to a primarily digital medium.

“A portion of it was just being in the right place at the right time,” she recalls to Billboard. “I found myself in a unique position to be able to be the bridge between the two. And it just so happened that nobody was speaking the digital language. I became the person—this was [when] Napster [was happening], when the industry was suing kids in college and doing everything in their power to squash the new business. I was one of the people who was like, ‘Wait a second, if we’re hearing that this is what they want and they’re seeking it out…’ It was very ‘flip the script,’ because up until then, it was the industry telling the people what they were going to get, the industry making those decisions. That’s completely changed.”

Today, the all-woman team at Girlilla Marketing leads social media initiatives and content creation for its clients, helping to develop online audiences, virtual events, digital monetization, analytics tracking and more. During her career, Smythe has worked with artists including Willie Nelson, Darius Rucker, Vince Gill, Blondie, and Dead & Company. She chairs the CMA board and serves on the boards of the CMA Foundation and Music Health Alliance.

Trending on Billboard

Now, Smythe is sharing the lessons she’s learned along the way in her memoir, Becoming Girlilla: My Journey to Unleashing Good — In Real Life, Online, and in Others, which releases via Resolve Editions/Simon & Shuster today (April 15). Her book also delves into Smythe’s personal journey including her 2018 breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Smythe was named a 2025 Advocacy Ambassador with the Susan G. Komen Center for Public Policy.

Jennie Smythe

Courtesy Photo

“[The book] really was a way for me to express my gratitude to the music business and the digital marketing community. It was a way to share my survivorship so that I could help other people. And my intention was to be able to be a support document for entrepreneurs and especially young women,” she says.

Billboard spoke with Smythe about writing her book, launching Girlilla Marketing, the importance of mental health advocacy and leading the next generation of women music industry execs.

Why was it important to you to share your life and career experiences in this book?

I thought I was going to write a business book about business lessons, anecdotal humor in the workplace, generational bridges, that kind of thing. But I got sick and our music community also lost several people to cancer, like [music industry executives] Jay [Frank], Lisa Lee, and Phran Galante. I had 12 rounds of chemo, six surgeries. [Part of me] was like, ‘Can I just go back to work?’ But I realized, ‘No, you can’t. This is part of your story now.’ Every single one of those three people–Jay, Phran and Lisa–called me every day when I shared my story [about her battle with breast cancer]. They all were in harder circumstances than I was. So I was like, ‘I want to do this for them.’ And the Nashville community, it is like a family. That’s one of the most special things, and no matter how big Nashville gets, we don’t lose that.

A conversation with your father led you to launch Girlilla Marketing. What do you recall about that?

I was 30, I had had a pretty successful career, and then my dad was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. I was in the hospital room with him and he said, ‘What would you do if your life was half over?’ When he asked me that question, in that moment, it drilled down to two different things: I want to start a digital agency and I want to travel more. I realized, “There’s never going to be a perfect time, a perfect amount of money—if I don’t do it now, I will not do it.”

Girlilla Marketing is an all-woman company. What inspired you to launch a female-first company?

I feel like through my whole career of working for other people, I only had the opportunity to work for one woman, and she was amazing. But I wished I would’ve had more opportunity to do that. So, I created what I wanted, the place I wanted to work, because it didn’t exist.

One of the key early moments in the book was when, during your career at Yahoo Music, you received a performance review from your former boss, Jay Frank. You received some feedback you didn’t expect.

That’s what made him my trusted mentor because he was like, “You’re so smart and you’re doing all the right things, but you’ve got to be human, or people won’t want to work for you.” I thought if you are the champion and you are the best, then you will be rewarded for that behavior. Not at all. Everything that has come to me in a good way has come because of a team mentality. It was a lesson in leadership.

What are some things were you able to implement because of that conversation?

How do you come into the office in the morning, no matter how stressed you are—do you say good morning to everyone, or do you just ignore everyone? When you are in a meeting and somebody is not prepared, instead of drilling somebody down to where they feel like they can’t get out of that hole, what do you do? Isn’t the job of a manager to lift them up?

What are some of the biggest myths that persist around digital marketing in music?

One of the myths is that [artists] have to create all the time. That’s not true. You do have to figure out what your cadence is, but if you are creative and you’re constant, you’ll be okay. Some people are too precious with it, they feel like they can’t, and we have to get them out of that.

With things like TikTok and A.I., so many things are swiftly changing in the industry. What do you think are some of the biggest issues?

Mental health. Giving people the space to create without the pressure of the analytics, which are glaringly upfront in every conversation that we have. Once a week, somebody comes in here ready to quit because they’ve been told that if they don’t hit a certain threshold, that they don’t have a career. I’ve been around artists my whole life and that’s not conducive to a creative career. My thing is telling artists constantly that they are the CEOs of their lives, and their digital ecosystem is part of it, but it’s a wide net.

Also, the mental health thing starts from the top. I am so lucky to be in this community with people like Tatum [Allsep] from Music Health Alliance, and grateful for people like at the CMA who put together the mental health fund. People talk about artists, but it’s also the people in the business that need support, like our touring families.

For those who are just starting out in digital marketing, what essential tools do they need to know?

I think just being an avid user, and you need to know how to shoot and edit content. It’s all video. This is the biggest merge of the decade. We used to have the creative people and the analytical people. To inform the creative, sometimes you need to understand what the market is requesting—very much the same conversation we had with Napster, when it was like, “So this is the most illegally downloaded file in Green Bay, Wisconsin—maybe we should go play there.” It’s also having somebody that can purposely come up with a creative strategy that also speaks to the analytical success to something, that’s the job for the next 10 years. That’s exciting because I think when I was in college, my [current] job didn’t exist. But along the way, everything I picked up mattered.

In July, popular influencer/podcast host Tinx took to TikTok to ask her followers a question: “Are labels and artists asking random people to make content about music and not say[ing] it’s an ad?” The answer in the over 700 replies to the video was a resounding and simple “yes.”

“Sound campaigns” have been an integral part of music marketing since TikTok took off in 2019, but they differ from other paid promotion campaigns on social media. Captioning a video with #ad, or another similar disclosure, is required by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) when companies “pay you or give you free or discounted products or services” in exchange for featuring their product in a video, but that has never been the standard for the paid promotion of a song. “Any essence of perceived authenticity can be stripped away when a creator tags a video as paid,” says one digital marketing agency CEO.

As a result, one major label marketer believes “75% of popular songs on TikTok started with a creator marketing campaign,” but says that there’s no way to actually track how many of the songs that go viral on TikTok do so organically or are boosted by thousands to hundreds-of-thousands of dollars’ worth of paid promo.

Trending on Billboard

When asked for clarification about whether or not promoting songs in the background of videos requires disclosure, a representative for the FTC said, “While we can’t comment on any particular example, that practice seems somewhat analogous to a product placement… When there are songs playing in the backgrounds of videos, there are no objective claims made about the songs. The video creator may be communicating implicitly that they like the song, but viewers can judge the song themselves when they listen to it playing in the video. For these reasons, it may not be necessary for a video to disclose that the content creator was compensated for using a particular song in the background in the video. We would evaluate each case individually however.”

While it is not, in most cases, an FTC violation to run undisclosed creator campaigns to promote singles on TikTok, Instagram Reels or YouTube Shorts, it remains a little-understood area of music marketing that many music fans are not aware is happening. “The beauty of Tiktok, for me, has disappeared because I’m super cynical and believe everything I see there, disclosed or not, is paid to be promoted,” says the digital marketing agency CEO. (Most of the sources in this story requested anonymity in order to speak freely about how these campaigns work.)

Often, digital marketing gurus will reminisce about the days of the Hype House bros and the D’Amelio’s TikTok reign, around the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which were considered the good ol’ days for creator marketing. At the time, it was expected for successful TikTok virality to translate into boosts in streams practically every time. “Back then, it made sense to pay over $10,000 a video for those famous kids to post your song. There was a high probability of [return on investment] ROI in 2020,” says a second digital marketing agency CEO. One creator manager says they remember a top creator at the time boasting about getting “$50,000 to just play the sound” in the background of a TikTok.

Typically, these creators would be instructed by an artist manager, a label, or a third-party digital marketing company (most times the latter) to perform a certain trend along with the song, like a dance or a certain filter, in exchange for money.

But these days, experts like George Karalexis, CEO of YouTube marketing and rights management company Ten2 Media, say it’s “more expensive and harder than ever to start a trend” online. As Billboard reported in 2022, TikTok tracks in the U.S. were streamed far less that year than they were in 2021, according to the most recent available data from Luminate.

Now, this unpredictability has led to top creators rarely fetching rates of over $10,000 for the use of a song in a video. Instead, digital marketers are spreading their budgets over many videos from smaller creators to make the illusion of a less-detectable groundswell of support. The second digital marketing agency CEO says today’s payment ranges from $25 for a micro creator (at or below about 10,000 followers) to $10,000 for a TikTok star to post the song.

Recently, a cottage industry of startups has popped up in the creator campaign space, automating the connection between smaller creators and artists looking to pay them to promote their songs. One of the leading companies, Sound.Me, for example, recently ran a creator campaign for “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” through their service. TikTok is also offering up a similar service with its “Work With Artists” feature inside the app, which allows qualifying creators (those with over 50,000 followers and living within a certain territory) to get paid to use songs, like Halsey’s cover of “Lucky,” in their videos.

Even when an artist is willing to spend a significant budget on one particular creator, that doesn’t mean the creator will always accept. Sound promos are known to be less lucrative for creators than other brand deals, like fashion or skincare, and thus it’s common for top creators to “shoot [the artist’s team] an outrageous number, knowing a sound campaign is not necessarily worth their time otherwise,” says the creator manager.

It is also far less common to ask for a specific type of video from a creator today. Instead, the second digital marketing CEO says “it’s not really about pushing specific creative. It’s just about finding the right creators for the artist’s target audience and kind of just letting the influencers run with creative freedom.”

All of this makes discerning the paid promotion of a song from organic enthusiasm more challenging than ever. Even more complicated, the creator manager says that it’s “best practice” for creators “who want to work with a specific brand to show for free that they are using the brand’s products anyway to attract their attention. Same goes for songs.”

The sign of true success for these campaigns is when social media use of the song grows far beyond the initial budget, encouraging unpaid creators to jump in and use the track, too, multiple digital marketing sources say. “The value is in the people [using the song] that aren’t being paid,” says Jeremy Gruber, head of artist marketing and digital strategy at management company Friends at Work. “Success is when we have 13 types of videos going on at once to the song,” adds one indie label marketer. “We can’t even tell what’s happening.”

Typically, these sound campaigns are conducted in phases, and while they are common, they are not expected for every single release, three label marketing sources say. $5,000 is the low-end for what two digital marketing agencies believe would be a fruitful campaign, but the spending can grow to $80,000 (or even into the six figures for rare cases) if it is a big-name artist and the song is reacting positively. Typically after the first round of the campaign, the team will watch and see if the song grows. If it does, then a next wave of spending will be opened up and seeded out to creators to stoke the flame.

Gruber believes an ethical gray area arises when artists’ teams offer money to music curation influencers to explicitly recommend a song without disclosing the transaction to viewers. Unlike a “product placement”-like promotion which simply streams in the background, these music curators use TikTok to talk to the camera, telling consumers to take action and check out new songs in exchange for undisclosed money, concert tickets or other perks. When asked about this type of promotion specifically, the FTC declined to comment on whether or not disclosure is needed.

It’s also common for record labels to turn to social media-based blogs, typically in the rap genre, like WorldStarHipHop, Rap, Our Generation Music and more which offer pay-to-play promotion on TikTok and other social platforms to create the appearance of organic online chatter. In one message exchange, reviewed by Billboard, a representative from Rap told a music company that “solo” posts go for $1,000, but they offer discounted rates for ordering in “bulk.” Typically, these payments are not disclosed to consumers.

While it might come as a surprise to some music lovers to learn how often these paid campaigns are used, the general consensus among the eight sources spoken to for this story is that it isn’t harming anyone to do it —at least not in the types of campaigns that resemble product placements. “Music, to me, is this beautiful art form and it is completely different from other ‘products’ in other industries [that run creator campaigns],” says the first digital marketing agency CEO. “We do feel that ethically we’re promoting content that is a net positive to society.”

It may not be as effective as it was a few years ago, but creator campaigns are largely believed to still be essential to market songs today, whether it’s on TikTok or on Instagram Reels or YouTube Shorts (which is increasingly common). Says the second digital marketing agency founder: “It’s still the best thing we have.”

This story was published as part of Billboard’s new music technology newsletter ‘Machine Learnings.’ Sign up for ‘Machine Learnings,’ and Billboard’s other newsletters, here.

Thirteen years ago, the then-unknown teenager Rebecca Black posted her song “Friday” to YouTube, hoping to spark her music career. We all remember what happened next. The song, which amassed 171M views and 881K comments on YouTube to date, was pushed up the Billboard charts, peaking at No. 58 on the Hot 100. “Friday” was a true cultural phenomenon — but only because it was a laughingstock.

“I became unbelievably depressed,” Black said of the song’s meme-ification — and the cyberbullying that came with it — on Good Morning America in 2022. “And [I felt] trapped in this body of what the world would see me as forever. I hadn’t even finished growing.”

Many music makers dream of waking up one morning and realizing a song of theirs has gone viral overnight. But, as Black’s experience shows, not all virality is created equal. At best, it can bring a Hot 100 hit, radio play and a slew of new, lifelong fans. At worst, it can be the artists’ worst nightmare.

Trending on Billboard

One such worst-case scenario recently took place with Gigi D’Agostino’s 1999 Italo dance track “L’amour Toujours,” which was recently co-opted by the German far-right. In a popular video posted to social media, a group of young men sang the song outside a bar on the German island Sylt, replacing the original lyrics with a Neo-Nazi slogan that translates roughly to “Germany to the Germans, out with the foreigners.” As they chanted the xenophobic lyric, one of the men raised his arm in a Nazi-like salute. Another put two fingers to his upper lip in a seeming allusion to Adolf Hitler’s characteristic mustache.

After that, several events in Germany, including Oktoberfest in Munich, looked into banning the song, and D’Agostino replied to an inquiry from German newspaper Der Spiegel with a written statement, claiming that he had no idea what had happened.

Granted, the circumstances of virality are rarely that bad, but songs commonly end up on an “unintended side of TikTok,” as Sam Saideman, CEO/co-founder of management and digital market firm Innovo, puts it. “We try to educate our partners that sometimes you cannot control what uses of your song [are] on the internet.” While Innovo “may plan a campaign to [pay creators to] use the song in get-ready-with-me makeup videos,” he explains, another user’s totally different kind of video using the song could become far more popular than the originally planned use, pushing the campaign organically onto another part of the platform and away from its target audience.

For example, Twitter and TikTok users twisted “Cellophane,” FKA Twigs’ heartbreaking 2019 ballad about unrequited love, into a meme beginning in early 2022. Oftentimes, videos using the song pair Twigs’ voice with creators that are acting melodramatic about things that are clearly no big deal. Even worse, one popular version of the audio replaces Twigs’ voice with Miss Piggy’s (yes, the Muppet character).

“Digital marketers are able to boost certain narratives they support,” says Connor Lawrence, chief marketing officer of Indify, an angel investing platform that helps indie artists navigate virality. “It happens a lot — marketers boosting a narrative that is most favorable to the artist’s vision to hopefully steer it.” Saideman says he likes to keep a “reactionary budget” on hand during his song campaigns in case they need to try to course-correct a song that is headed in the wrong direction.

But digital marketing teams can’t do much to fix another bad type of song virality: when songs blow up before the artist is ready. “I am actively hoping that my baby artist does not go viral right now,” says one manager who wished to remain anonymous to protect their client’s identity. “They need to find their sound first.” Omid Noori, president/co-founder of management company and digital marketing agency ATG Group, adds, “It’s a real challenge when someone goes viral for something when they aren’t ready to capitalize on it, or even worse, the song that took off sounds nothing like anything you want to make again.”

Ella Jane, an indie-pop artist who went viral in 2020 for making a video that explained the lyrics to her song “Nothing Else I Could Do,” says that going viral early in her artistic career had positive and negative effects. She signed a deal with Fader Label and boosted her following, but she’s also still dealing with the downsides four years later. “I’m grateful for it, but I think because my first taste of having a successful song was inextricable from TikTok, it has cast a shadow on my trajectory in some ways,” she says.

Over her next releases, Jane says she chased the algorithm, like many of her peers who experienced TikTok hits early in their careers, trying out lots of different video gimmicks to hook listeners. “It doesn’t reflect who I am as an artist now,” she says. “That feeling is addicting, and you feel like you’re withdrawing from it when your videos don’t hit. It can leave artists at a point where they’re obsessed with metrics.” This obsession has been reinforced by some record labels who use metrics as the only deciding factor in whether or not to sign a new artist.

“This is no different than hitting the lottery,” Noori says. “Imagine you get the $100 million jackpot on your first try… It makes artists feel like failures before they even really get started.”

As artists are increasingly instructed by well-meaning members of their team to make as many TikToks as possible, some have turned to sharing teasers of unfinished songs as a form of content — which have occasionally gone viral unintentionally, despite not even being fully written and recorded. That’s what happened to songs by Good Neighbours, Leith Ross, Katie Gregson MacLeod and Lizzy McAlpine, leading many of them to rush to finish recordings so they could capitalize on their spotlight before it faded.

“People put a lot of pressure on the recorded version,” says Gregson MacLeod, whose acoustic piano version of her song “Complex” went viral before she had recorded the official master. “If it is not exactly like the sound that went viral, if you don’t sing the words in the exact same way or use the exact same key, sometimes people decide, ‘We’re not having it.’” While she says she was ultimately happy with how it all turned out, not everyone is so lucky. Within two weeks of the song’s virality, she rushed to release a “demo” version to match the rawness of her original video, as well as a produced version, earning her a combined 43 million plays on Spotify alone.

McAlpine, however, decided to run away from her unfinished viral song. After posting a popular video of herself playing a half-written song, she told her fans in a TikTok video, “I’m not releasing that song ever because I don’t like it. It doesn’t feel genuine. It never felt genuine. I wrote it for fun. It wasn’t something I was ever going to release, or even going to finish… That is not who I am as an artist; in fact, I think I’m the opposite… I’m not concerned with overnight success. I’m not chasing that… I want to build a long-lasting career.”

Noori says TikTok virality in particular has led to a “huge graveyard of one-hit wonders,” something that is far more common today than the bygone days of traditional, human gatekeepers. “With the algorithm, how do you even know who saw your content?” he asks.

Still, there’s an argument to be made that perhaps, as P.T. Barnum famously said, “There’s no such thing as bad publicity.” “I’ve been thinking about that idea a lot and whether or not it is true for virality,” says Saideman. “And it’s hard to say.”

Black ultimately reclaimed “Friday” and her music career in 2021 by getting in on the joke, turning the decade-old cult hit into a hyperpop remix, produced by Dylan Brady of 100 Gecs and featuring Big Freedia, Dorian Electra and 3Oh!3. From there, Black continued to release music as a queer avant pop artist and played an acclaimed DJ set at Coachella in 2023. Still, the original version of “Friday” is her most popular song on Spotify by a long shot, even though it was released before the streaming era began.

“The beauty and curse of these platforms, especially TikTok today,” Saideman says, “is that they are remix platforms. When you put your music on them, you are opening your music up creatively to other people using it in positive and negative ways. You can’t have one without the other.”

This story was featured in Billboard’s new music technology newsletter ‘Machine Learnings.’ Sign up to receive Machine Learnings, and Billboard’s other newsletters, for free here.

Consumers and the marketers who sell to them agree: They “hear from too many influencers — and not enough real people — in marketing.” That’s according to an iHeartMedia study the company unveiled Wednesday (Sept. 13) that explores the gap between marketers and their audiences and tries to identify biases and blind spots.

Though the wording is a little bit confusing — most influencers are still real people, with a few exceptions, i.e. Lil Miquela — this conclusion aligns with what many music marketers have been saying for over a year. In essence: Throwing bags of money at popular TikTok accounts and hoping this will magically lead to music discovery and drive streams is not an effective or efficient approach.

Marketing spends “started becoming less effective when people and brands were really looking at people’s influence based upon follower count,” says Coltrane Curtis, founder of the marketing agency Team Epiphany. Curtis has been an active proponent of the notion that “the pay-to-play model is ineffective, oversaturated and counterintuitive.” “Influence is about trust,” he adds. “When you start seeing everyone paying for it, you feel duped and taken advantage of.”

Last year, the music consulting agency ContraBrand analyzed TikTok’s top 200 from the first half of 2022. The company determined that “paid-for tactics, such as influencers and ads, accounted for success in under 12% of the platform’s viral tracks.” In 2020, as industry after industry awoke to TikTok’s power as an advertising tool and started pouring money into the platform, “you would literally have an influencer’s rate to post go from $500 to $1,500 in a day,” ContraBrand co-founders Sean Taylor and Jacorey Barkley told Billboard last year. “That was happening day in, day out. Influencer campaigns have become both less accessible and less effective.”

iHeart laid out its new study — and gently prodded marketers to think about spending more on podcast advertising (a sector in which the company is highly invested) — during a chat between Conal Byrne, CEO of the company’s digital audio group, and author and podcast host Malcolm Gladwell in Manhattan.

The conclusions of the study echoed many of the think pieces written after Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election: Coastal cities are out of touch with large swathes of the country. In this case, the focus was on marketers themselves, who spend time in their own “bubbles,” never taking the time to notice that others might not share their passions and priorities.

This point was driven home through a barrage of statistics. While all the marketers surveyed were familiar with NFTs, 40% of consumers had never heard of them. Marketers have the hots for artificial intelligence — 66% “are excited about the potential” the tech “will unlock for society” — but consumers are tepid about the robot-driven future, with only 39% excited. Marketers are apparently “motivated by fortune, fame and fear;” “consumers are motivated by friends and family.”

The study did not address itself to the music industry. But in her opening remarks, Gayle Troberman, iHeart’s chief marketing officer, sounded much like a major label executive. There is “more competition than ever before… for consumer attention,” she said. “We’ve never had more data, and yet, it’s never been harder to win.”

From 2001 to 2004, the music industry produced a steady stream of new artists with big hits: At least 30 first-timers landed in the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 each year. In 2022, only 12 new acts managed the feat (plus a pair of songs from the Encanto cast). “This is the hardest time to break through and market music,” one manager tells Billboard.

It’s not for lack of trying: In recent years, labels have been signing acts at whirlwind speed, yet this surge of new signings hasn’t yet amounted to a surge of new stars. And some executives worry that the dry spell is partly due to the recent wave of signings, claiming that the majors have inked deals at a rate beyond their ability to provide service.

“The over-signing of [the] COVID [era] is now a pain point at every label,” says one manager with multiple acts on majors. If staff growth doesn’t keep up with roster growth, artists don’t necessarily get the care they need to level up. “No one has enough product managers. So they’re all getting crushed.”

“It is not humanly possible for a product manager — the person responsible for the story of the artists, the story of the music — to creatively, strategically and efficiently implement marketing for 20 artists at one time,” says Craig Baylis, a former major-label product manager who runs the boutique publishing company Eighth & Groove. Record companies often “aren’t getting the best out of [their staff] because they are ramming them with all of these artists that they’re not even getting the chance to know.”

All the major-label groups have broken new artists in the last few years, of course, whether it’s Olivia Rodrigo (Universal Music Group), Steve Lacy (Sony Music) or Zach Bryan (Warner Music Group). In a January letter to staff, UMG chairman/CEO Lucian Grainge reaffirmed the company’s commitment to this task, writing, “We diligently work, day in and day out, to break our artists and songwriters.” While speaking with investors last year, Sony Music chairman Rob Stringer said “creative staff,” which encompasses A&R, marketing, product managers and artist relations, had increased at a faster rate than artist roster size, helping launch new acts onto the streaming charts.

Roster size numbers are difficult to come by, but in 2017, a study organized by the RIAA found that major labels had signed 658 artists that year, up from 589 in 2014. Although the RIAA hasn’t released a follow-up, many lawyers and executives say the rate of signings has climbed since that report. Two senior executives believe the number of deals is now as high or higher than it has ever been; Sony Music told investors that new signings rose 32.4% between 2017 and 2021.

The recent wave of signings is in part a byproduct of streaming becoming the main revenue source at the majors. The biggest streaming services pay rights holders according to their share of total plays on the platform. But low-cost distribution has brought a “vast and unnavigable number of tracks” into the music ecosystem, as Grainge put it in his staff memo. Streams for those tracks eat into big record companies’ piece of the pie. If tens of thousands of new tracks are added to streaming services daily, “then [major-label] market share is going to be diluted by default,” Stringer explained last year.

Signing more is a way of fighting back. “For major labels, independents and distributors, it’s all about volume of signings now,” says Andreas Katsambas, who was a senior vp at BMG before joining the analytics company Chartmetric as president/COO.

This puts major labels in a bind: They need to sign and release more to keep market share up, but this makes it harder for each artist signed to get the attention they need to break through.

“Intelligent marketing is not going to be a facet of developing artists today if record companies are going to continue doling out artists, singles and projects at the frequency that they do,” says Baylis. “There is a high level of fatigue that product managers are experiencing.”

A former major-label employee who left to go into management agrees that product managers and marketers tend to be “completely overworked.” “A digital person may have 60 projects,” he adds. “It’s crazy.”

Mike Caren, founder of the publishing company and independent label APG (and former president of global A&R at WMG), points out that “even the best marketer is limited by the number of hours in the day and days in the week.” He adds: “Executing an artist’s vision is time-intensive, and the best artists challenge their teams with unique ideas that take a lot of time to properly deliver. Capacity is a key metric to determine when choosing a label or team.”

This may be especially true today, when the ability to grow audiences seems increasingly like the most important service a label can offer. Artists no longer need to turn to majors for national and international distribution or studio-quality recording equipment; now, anyone can get those things from their laptop while sprawled on the couch. Instead, “gaining awareness is the most challenging thing for anyone that releases music,” Katsambas says. “Awareness more than anything else, and then engagement and retention.”

Are those goals compatible with high-volume signing? “It’s hard creating a game plan for longevity for some of these artists that are really talented and deserving,” Baylis says, “because executives are charged with just feeding the beast called the DSPs.”

-

Pages

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio