crossover

When Island/Republic/MCA Nashville released Chappell Roan’s “The Giver” on March 12, the move extended a pop/country crossover trend that has seen the likes of Shaboozey, Beyoncè and Post Malone successfully hop genre fences.

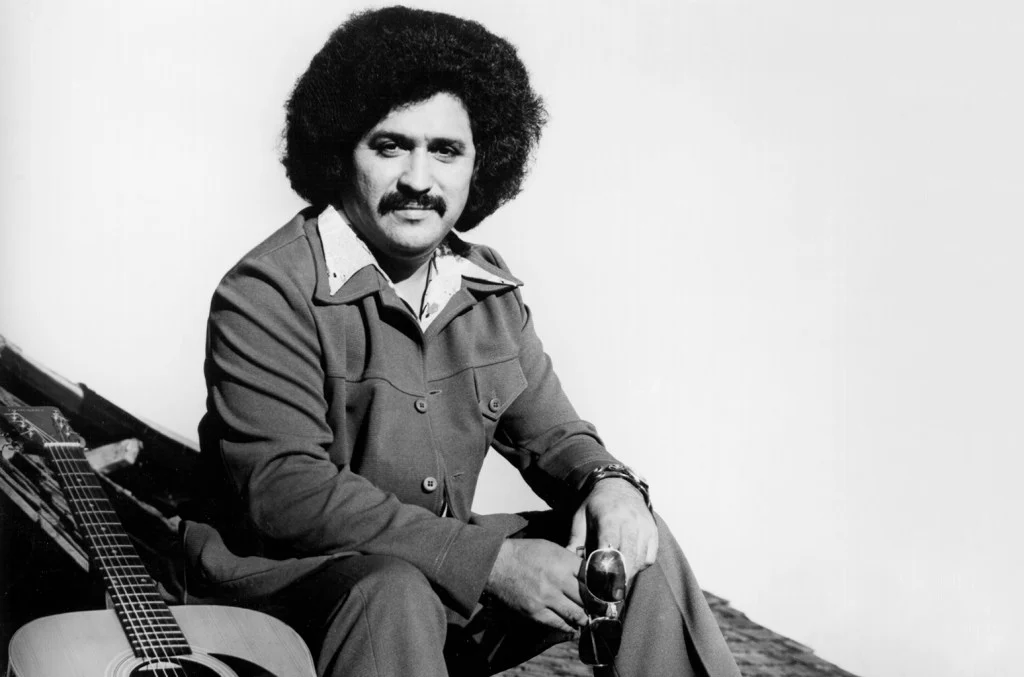

As current as the development may be, it’s also a case of history repeating. The release comes 50 years after Freddy Fender’s “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” reigned on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart dated March 15. “Teardrop” went on to top the Billboard Hot 100 on May 31, 1975, in the midst of a crossover wave.

“That song just caught fire,” says Country Music Hall of Fame member Joe Galante, who handled marketing for RCA Nashville at the time. “It sold, and that was one thing that made it difficult for people to walk away from, was the sales numbers. Even as a competitor, I was sitting there going, ‘How the hell is this happening?’ And you start looking at the numbers and you went, ‘Well, that’s how it’s happening.’ ”

Trending on Billboard

Fender’s success was not an isolated example in 1975. From March 8 through June 7 that year, four different singles reached the Hot 100 summit while simultaneously becoming country hits: Fender’s “Teardrop,” Olivia Newton-John’s “Have You Never Been Mellow,” B.J. Thomas’ “(Hey Won’t You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song” and John Denver’s“Thank God I’m a Country Boy.”

When Fender was at No. 1, at least seven more titles on that same country chart made significant inroads on the Hot 100 and/or the Easy Listening chart (a predecessor of adult contemporary), including Jessi Colter’s “I’m Not Lisa,” Elvis Presley’s “My Boy” and Charlie Rich’s “My Elusive Dreams.” Additionally, Linda Ronstadt peaked at No. 2 on country with the Hank Williams song “I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still in Love With You),” weeks ahead of the crossover follow-up “When Will I Be Loved.”

Throughout the rest of 1975, the country crossover trend continued with Newton-John’s “Please Mister Please,” Fender’s “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights,” Glen Campbell’s “Rhinestone Cowboy,” The Eagles’ “Lyin’ Eyes,” Tanya Tucker’s “Lizzie and the Rainman” and C.W. McCall’s “Convoy.”

Then, as now, plenty of fans and critics debated if some of those titles belonged on the country station.

“For me, the answer to ‘What is country?’ is: the records that the country audience, at that time, thinks belong on a country radio station,” says Ed Salamon, a Country Radio Hall of Fame member who became PD in 1975 of WHN New York.

Salamon programmed plenty of crossover music, sometimes incorporating songs that weren’t being promoted to the station, in an effort to appeal to a metro audience that didn’t have much history with the genre.

WHN became a major success story — just five years later, the Big Apple got a second country radio station — but its crossover mix yielded as much hostility from Nashville as praise. Part of that was directly related to the corporate source of some of the records on the playlist: Denver, Newton-John and The Eagles were all signed out of New York or Los Angeles.

“There was such a pushback about what I did that I didn’t fully comprehend it at that time,” Salamon reflects. “I was taking the space that the Nashville label thought should go to one of their records on a country radio station, and I was giving it to the pop division.”

Exactly one year after Fender topped the country chart, crossover material in 1976 had subsided. The number of crossover singles was the same, but none of them had the same level of impact.

“It’s the luck of the draw,” says Country Radio Hall of Fame member Joel Raab, a consultant and former programmer for WHK Cleveland.

Two of those 1976 crossovers, Cledus Maggard’s “The White Knight” and Larry Groce’s “Junk Food Junkie,” were novelty records, distinguishing them from the 1975 batch.

“We’d seen success in the crossover the year before,” recalls Country Radio Hall of Fame member Barry Mardit, whose programming history included WEEP Pittsburgh and WWWW Detroit. “If those songs weren’t consistently coming, we were therefore looking for something else that would grab the ear, that would grab the attention of the listener, like a novelty song does.”

Crossover records would continue through the rest of the ’70s, with Crystal Gayle, Dolly Parton, Ronnie Milsap, Kenny Rogers, Eddie Rabbitt and a couple of Waylon Jennings & Willie Nelson duets benefiting. In most cases, those happened when one or more label executives were enthusiastic enough to take a risk. Record companies had to be judicious since radio stations relied heavily on local sales reports for research.

“You had to have product in stores in order for people to do sales checks,” Galante notes. “So it wasn’t as simple as just saying, ‘Oh, I think I’ll go do this.’ You’ve got to get the goods in stores, and if it didn’t move and they [were returned], you got a double whammy. And you’d spent the money. So you were careful about your shots, and you didn’t go willy-nilly trying to cross over a record.”

Similarly, artists often err when they purposely attempt to cross over. It’s an issue that country learned the hard way in the aftermath of the 1980 Urban Cowboy soundtrack.

“The Urban Cowboy sound was a moment,” Raab says. “It wasn’t a trend. It was just a bunch of really good hit songs that went with a movie — and those songs, by the way, were all pretty country: [Johnny Lee’s] ‘Looking for Love’ and [Mickey Gilley’s]‘Stand by Me.’ These were just really good country records. And because the movie was so popular, [some artists] said, ‘Oh, you know, I’ll be more pop.’ And they made these really bad pop-sounding records in the early to mid-’80s.”

The 2025 version of crossover is a little different — streaming data has helped identify the songs that work across formats, influencing the trajectory for music by Morgan Wallen, Ella Langley & Riley Green, Marshmello & Kane Brown, HARDY, Jelly Roll and Dasha.

Artists are interacting more freely across genre, with pairings of Kelsea Ballerini & Noah Kahan, Thomas Rhett & Teddy Swims and Post Malone & Wallen all on the current Hot Country Songs chart. And, Galante points out, country acts are playing stadiums and arenas in major markets, unlike in the ’70s, when they were mostly in small theaters in midsize metros.

As a result, there’s less incentive for country artists to refashion their music in a play for pop success.

“Country is just so big in its own right,” Mardit says, “that they don’t need to do that.”

When Beyoncè announced the March 29 release of what’s expected to be a country-leaning album, Cowboy Carter, she alluded to a moment when she felt unwelcome in the genre.

But current chart numbers suggest that the carpet has been rolled out for her, assuming she’s willing to keep walking the path. Her single “Texas Hold ’Em” jumps to No. 33 in its sixth week on the Country Airplay chart dated March 30, while it remains at No. 1 on Hot Country Songs. The Airplay position is lower than the slots the song occupies on other genre charts, where she has been historically established. But country radio develops slowly. Only two of the 32 songs ahead of her on Country Airplay — Nate Smith’s “Bulletproof” and Keith Urban’s “Messed Up As Me”— have charted for six weeks or fewer. The performance of “Texas Hold ’Em” suggests that the genre may be as open as it ever has to figures invading country from other entertainment formats.

“I kind of see things starting to open up,” says Country’s Radio Coach owner and CEO John Shomby.

Trending on Billboard

Beyoncè is hardly the only artist making a move into the format from another entertainment base. Post Malone spent 18 weeks on Country Airplay in a pairing with the late Joe Diffie, Diplo has released two country-shaded projects, and Lana Del Rey is reportedly recording a country album. Additionally, actors Charles Esten and Luke Grimes recently released their debut country albums, contemporary Christian artist Anne Wilson has signed with Universal Music Group Nashville, and retired St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Adam Wainwright made his Grand Ole Opry debut on March 9.

There’s no guarantee that any — let alone all — of them will stick. But it’s not like country music is a closed society.

“Take a look at Jelly Roll,” Shomby says. “This guy was a rapper, for crying out loud — he wasn’t even a famous rapper, but he was around. He’s welcome with open arms.”

It hasn’t always been that way. There’ve been plenty of figures from other music formats — such as Jessica Simpson, Connie Francis and La Toya Jackson — who made brief forays into country, then disappeared. So did former NFL quarterbacks Terry Bradshaw and Danny White, plus actors Dennis Weaver and Maureen McCormick.

The country music business has long been skeptical of people it perceives as carpetbaggers. Even artists who’ve had some success when jumping into country — such as Tom Jones, who scored a No. 1 single with 1977’s “Say You’ll Stay Until Tomorrow” and a top five with 1983’s “Touch Me (I’ll Be Your Fool Once More)” — have been flummoxed by its expectation of a commitment.

“With country stations, if you don’t record country all the time, they feel then that you’re not a country artist,” he complained in ’83. “If you only come out with an occasional country album, it’s hard to get it played on some stations because they stick with their regulars.”

R&B and adult contemporary stations, he allowed, operated with the same sort of provincialism.

But plenty of artists have made successful transitions into country, too — Conway Twitty, Dan Seals, John Schneider, Exile and Darius Rucker, to name a few. All of them faced skepticism on their way to acceptance. Seals’ former manager, Melody Place COO Tony Gottlieb, recalls when Seals was confronted about it on late-night TV.

“This guy who’s from Nashville — obviously tuned into the Nashville scene — asks Dan, ‘What do you say about failed pop artists coming to Nashville to pursue country music careers?’ ” recalls Gottlieb. “Of course, as Dan’s manager, I wanted to strangle the guy because he had just ambushed him right on live TV.”

Seals had actually been raised on country — Ernest Tubb and The Louvin Brothers — and he proved himself over the long haul. His fourth single, “God Must Be a Cowboy,” became the first of 16 top 10s, including 11 No. 1s. Like Twitty and Kenny Rogers before him, Seals did three things that most successful outsiders have done to become insiders: He committed to country; his music targeted the center of the format, not its sonic periphery; and he recorded high-quality songs.

“You can be new one time,” observes Mike Reid, who segued from his original career as an all-pro NFL lineman into a country singer-songwriter in the 1980s. “But you better always be good, you know. The audience is going to tell you if you’re any good or not.”

The audience likewise will decide whether members of the current crop — including Beyoncè and Post Malone — make an authentic connection with their country endeavors. Pushback is to be expected in the beginning.

Maverick partner Clarence Spalding saw that play out in the early 1980s as the road manager for Exile, which began making country records five years after a No. 1 pop single with “Kiss You All Over.” Spalding’s current management client list includes Rucker, who was known as the frontman for multiplatinum pop/rock band Hootie + the Blowfish before he recorded as a solo country artist.

“There’s a divide — there always is — when anything new comes in town,” Spalding notes. “It’s, you know, ‘That’s not country,’ ‘That is country,’ ‘What is country?’ I don’t know the answer; it’s a subjective thing. If the consumer accepts it as country, then it’s country.”

Transitioning into the genre might actually be easier now than ever before for multiple reasons, beginning with the makeup of the music itself. From the soul-tinged sound of Thomas Rhett’s core hits to the hard-rock influence in HARDY’s material, the genre is much more flexible.

“It’s a wider avenue to go down, and so it’s going to be more forgiving than if it were the traditional country song,” suggests Reid. “You better not go near that unless you know what the hell you’re doing.”

Additionally, Taylor Swift’s reverse transition more than a decade ago, from country singer to pop stadium-filler, has made genre-hopping more acceptable.

“She could probably put a country album out tomorrow, and nobody’s going to question anything,” Shomby says.

Like Swift, Beyoncè, Post Malone and Del Rey are all courting country while they are still going strong in their original genre. Many of their predecessors tried to jump to country only when their pop careers had sunk, creating a negative view of the practice in Nashville.

Radio programmers are operating differently, too. Many modern PDs came into country from other formats and view country’s boundaries with more elasticity, and since they often work for stations in multiple formats, they’re less concerned about the exclusivity of any single genre. Plus, digital service providers have created a more fluid environment.

“Clearly the technology has changed this,” says Gottlieb. “This discussion would not have occurred in the same context six, eight years ago before the DSPs had such a major impact on what we’re doing.”

Perhaps the biggest factor, though, is sheer quality. The country industry has historically felt demeaned by the rest of the business. The fact that visiting artists are approaching country while they’re hot is viewed positively on Music Row. But the quality, and authenticity, of the work weighs most heavily in the reception it receives.

“If it’s a really, really good song, I hope they play it,” Spalding reasons. “And if it’s not a really good song, if it just has a big name on it — you know, don’t spread the crap.”

Subscribe to Billboard Country Update, the industry’s must-have source for news, charts, analysis and features. Sign up for free delivery every weekend.

-

Pages

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio