Cover Story

Page: 4

On the brick wall facing the Pittsburg Hot Links parking lot, a mural memorializes the small East Texas town’s most famous citizens, including Mean Gene the Hot Link King and Homer Jones, the New York Giants receiver who invented spiking the football after a touchdown. Soon enough, Pittsburg native Koe Wetzel could be right up […]

It’s a Thursday afternoon at a studio in Miami, and Emilia is getting glammed up for a Billboard Español cover shoot. She’s wearing a baby-pink silky robe and striped slippers, and her equally silky, chocolatey brown hair is picked up in rollers as she navigates through her playlist for the perfect song to get ready. She skips through female anthems by Beyoncé, Shakira, Britney Spears, Nathy Peluso and Doechii before selecting Rihanna’s “Don’t Stop the Music.” She sings along and dances to the beat slightly, not to mess up her wavy bucles and makeup.

“Before, to give myself confidence when I went on stage, I would tell myself: ‘You are Rihanna! You are Rihanna!’ But someone on my team recently told me: ‘Now you have to say to yourself, ‘You are Emilia! You are Emilia!’ And believe it,” she gushes.

Trending on Billboard

She is Emilia. And she’s on the verge of a global musical breakthrough as she prepares a 2025 tour across Spain, plans her first U.S. concerts in the U.S., and just recently made her debut at Brazil’s Carnival this past weekend.

In 2024, the Argentine artist earned her first No. 1 hit on the Billboard U.S. Latin Airplay and Regional Mexican Airplay charts with “Perdonarte ¿Para Qué?,” her collaboration with Los Ángeles Azules; she became the first Argentine act to be nominated for best pop vocal album at the Latin Grammy Awards with her sophomore set, .mp3; she was TikTok’s most-viewed and Spotify’s most-streamed artist in Argentina (the first female artist to do so); she sold out 10 shows at Movistar Arena in Buenos Aires in 10 hours — breaking the record previously held by Luis Miguel — and became the first Argentine female artist with four sold-out shows at the city’s Estadio Vélez, to name a few milestones.

Now, Emilia is making a serious bid for international expansion in 2025 that includes her first time at Brazil’s Carnival, where on Feb. 23 she performed “Bunda” with Luísa Sonza, her first track from an upcoming EP; a spring tour across Spain with three dates at Madrid’s Movistar Arena (formerly WiZink Center); and spending more time in Miami not only to be closer to her label, Sony Music Latin, and manager Walter Kolm, but to connect with artists and producers from different territories and develop her career further — a tried-and-true strategy that others have taken before her, including Karol G and Manuel Turizo.

“In Argentina, there are producers that I continue to work with and who are friends. I have everything there; it’s everything for me,” she says. “But I made the decision to come to Miami for a while to work and try new opportunities. I’ll always be returning home anyway. I can’t let that go. But I think what happens at the industry level here in Miami is very big. You come across new artists and producers all the time. And it’s good to experiment.”

Natalia Aguilera

Leaving the comfort of a home territory that sees you as a superstar has long been a challenge for Latin American artists. But thanks to an open-minded attitude, today, Emilia has positioned herself as a versatile pop act who can easily navigate from reggaetón to romantic ballads to cumbia to Brazilian funk and, most recently, vallenato alongside Silvestre Dangond on “Vestido Rojo.”

“She understood that she had to have her base in her home country first. She had to break into her country in every sense, in consumption, transcend that consumption in ticket sales, media visibility, visibility with brands,” says Esteban Geller, GM at Sony Music U.S. Latin. “First, she conquered her country, then the neighboring countries like Chile and Uruguay, and little by little setting foot in territories like Spain, Mexico and Colombia, while simultaneously building her story in the United States. She understood perfectly what her space was in the music scene and that what she did with Los Ángeles Azules and with Silvestre brought her closer to a more commercial space, which is also fantastic. The path has been natural.”

Emilia is already dolled up in a Y2K-inspired outfit for the photo shoot: denim mini skirt, bubblegum-pink zip-up hoodie, glitter stilettos and a fur cap that easily gives off Baby Phat clothing vibes. On her bottom eyelashes is a set of shining diamonds — eye accessories that are signature to her look. Doja Cat’s “Wet Vagina,” from her female-heavy playlist, plays in the background as she flirts with the camera with pure confidence and sensuality — something she’s worked on over time, striking that balance between sexy ingenue and likeable girl next door.

“I was always very outgoing, but I feel that today, I feel more confident with myself than ever. That took time, effort and therapy,” she says.

María Emilia Mernes Rueda, 28, was born in Nogoyá, Entre Ríos, a farming town about a five-hour drive from Buenos Aires. She’s the only child to a baker father and a cook mother. Her grandfather, a plumber but also the only musical reference in her family, gifted her a guitar when she was young so she could start taking music lessons. Growing up, her love for music expanded to uploading covers on Instagram and forming part of a local cumbia group with friends. It was a passion she never believed could go beyond a hobby.

“I thought that dreaming of being an artist, of stepping on stage and being in that world, was impossible. Super far away,” she says. “I never thought I would be able to become a professional in this and be a singer. I saw it as impossible because of where I was from. The opportunities are usually in Buenos Aires, where the casting and music producers are.”

Natalia Aguilera

But her life took a radical turn when the videos of herself playing the guitar and singing covers on social media caught the attention of Uruguayan band Rombai. At the time, the cumbia-pop group gained popularity in South America and was in search of a new female vocalist. Emilia’s first time onstage with the group was in November 2016, when she performed for 12,000 fans at the Velódromo in Uruguay. Three months later, she was performing at Chile’s coveted Viña del Mar Festival and won a Gaviota Award — an experience she describes as a “great opportunity” and “a trampoline” in her career. “The real challenge,” she says, came two years later when she decided to go solo.

In 2019, Emilia signed a record deal with Sony Music Latin and a management deal with Kolm (her former manager with Rombai), becoming the first female artist to sign with Kolm, who also manages Carlos Vives, Maluma, Wisin and Xavi.

“When she told me she wanted to go solo and make the music she liked the most, I saw her with such determination that I decided to be by her side,” Kolm says. “She is very charismatic and has her own initiative.”

Excited for what the future holds, he adds: “She moved to Miami to direct her career from the USA. Emilia has all the potential to be a global artist. She always knew where she wanted to go. This is just the beginning of a career that will be huge.”

Shortly after her debut solo single, “Recalienta,” co-written with Camilo and Fariana, Emilia earned her first entry on a Billboard chart with her Darell collaboration “No Soy Yo,” which debuted and peaked at No. 38 on Latin Pop Airplay in February 2020. She also scored chart entries with “La_Original.mp3,” with Tini; “Tu Recuerdo,” with Wisin and Lyanno; and “Como Si No Importara,” with Duki.

The lattermost song — about a secretive and daring relationship on which her rapper boyfriend Duki’s chanteos lace with Emilia’s dulcet vocals — gave the artist her first entry on the Billboard Global Excl. U.S. chart in August 2021. The downtempo sultry reggaetón song peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard Argentina Hot 100 in 2021. Emilia then released “Esto Recién Empieza,” which reached a No. 9 high on the Argentina Hot 100 in March 2022.

Natalia Aguilera

At that point, Emilia and Duki had been dating for a year; the couple made their relationship public at the 2022 Premio Lo Nuestro, where they performed “Como Si No Importara.” The collaborations have boosted both artists. Duki is a trap star, so Emilia has helped broaden his appeal to tweens. Emilia is very much a pop star, and dating Duki has given her street cred.

“We may seem different from the outside, but we are actually very similar, and we have almost everything in common. The only thing we don’t have in common is that I like sushi and he doesn’t,” Emilia says with a laugh as she opens up about her boyfriend with face tattoos. “But in general, we share everything, and we have a very nice relationship. We give each other feedback all the time. I love listening to him talk, to get advice from him. Beyond being an incredible artist, he’s a very intelligent, very cultured person. Sometimes he comes into the studio with me and we write together. We’re very passionate about the same thing and it’s beautiful to be able to share it without egos, without selfishness. It’s very genuine, and in a very healthy way.”

Despite Emilia’s celebrity in Argentina and her increasing presence abroad, it wasn’t until last year that the catchy cumbia “Perdonarte Para Qué?” with Los Ángeles Azules gave Emilia her first No. 1 on the Latin Airplay and Regional Mexican Airplay charts. It was a full-circle moment for the once teen girl who had a cumbia band back home.

“From the first time I heard it, I said, ‘100% yes!’” she exclaims. “I remember that it didn’t take me even two days to get into the studio and record it. I was so excited that they wanted to make a song with me, that they had taken me into account, being such legendary artists of Mexican culture and the world.”

Elías Mejía Avante, founding member of the Mexican group, says: “We are happy, but above all grateful to be part of this great musical milestone for her. It will always be an honor to be able to merge the talent of Mexico and Argentina, seeking to infect as many hearts as possible with our cumbia. We feel that therein lies the magic, in bringing joy and authenticity with music from the hand of one of the greats of Latin pop music today.”

Natalia Aguilera

Meanwhile, in her native country, Emilia’s a force to be reckoned with.

She’s placed 39 entries on the Billboard Argentina Hot 100 chart, 20 of those in the top 10 and five hitting No. 1. Her longest-leading hit to date, “Una Foto (Remix)” with Mesita, Nicki Nicole and Tiago PZK, ruled for 10 weeks in 2024 — the third-most behind Karol G’s “Si Antes Te Hubiera Conocido” (16 weeks atop the chart) and Valentino Merlo and The La Planta’s “Hoy” (11 weeks). Emilia has released two studio albums: the ultra-personal Tú Crees en Mí? (2022) and her early-2000s nostalgic set, .mp3 (2023). The latter was Spotify’s second most-streamed album of 2024 in Argentina, following Luck Ra’s Que Nos Falte Todo.

That success on the charts translated to ticket sales.

In April 2024, she kicked off her .mp3 tour with a historic 10-night stint at the Movistar Arena in Buenos Aires between April and May, later adding four shows at Vélez Sarsfield Stadium in October.

“With artists in development, we’ve had extraordinary success with Emilia and her 10 arena [shows], where she played to over 290,000 people,” Marcelo Figoli, founder and owner of Fenix Entertainment, who produced the shows, previously told Billboard, confident that Emilia “is going to be a big deal in 2025.”

“I underestimated it. I usually set my expectations low, so I don’t disappoint myself,” Emilia admits. “We came out with the ticket sales, and I hadn’t done any shows for my album [.mp3]. We came out with the album in November and at the beginning of December the tickets were sold out. I remember that my team had said that we were going to book 10 Movistar Arena shows because that was the idea. And I was like, ‘I would love it, obviously, a residency at the Movistar Arena, but I see it as difficult.’ I felt like we were going to sell three, four at most, but suddenly it was 10 in 10 hours.”

“The live show is the other big leg of this industry,” Geller adds. “She’s an artist who not only works in one vertical of the business, but also has visibility in the fashion, brand and music sectors and has transcended into selling tickets, which is the best thing. She is already proving it with shows. The success she had in Argentina, the huge success she is having in Spain, that is happening because music is starting to transcend to other spaces, which will surely lead her to a long career. That’s the faithful conclusion that we are on the right track.”

The shows were also a test of resilience in other areas.

“I was rehearsing for the Movistar shows and my dad got cancer… Of the most important things in my life, the two came together and it was very emotional for me, but I was able to handle both,” she says. “Today I have my dad with me, and he can see everything I’m doing. I learned to know myself a little better. What my limits are. To make mistakes and not be so cruel to myself. To value the real people I have in my life… that family is the most important thing. I learned that I love to work and that I must enjoy the moment and not live so much in the future.”

Natalia Aguilera

But living in the future is inevitable for someone on Emilia’s path.

She’s preparing for her 2025 concerts in Europe and Latin America by working out five to six days a week, something she never did before, but is essential for next-level shows.

“The show requires a lot of cardio. You have to sing and dance, you need a good diaphragm, lungs with air, endurance. I hated training! I wouldn’t touch a weight for nothing!” she says, giggling. “But if I hadn’t trained, I wouldn’t be able to do it. Exercise has become something important for me and it does me good. I feel strong and confident.”

Emilia is now in her second outfit for the photo shoot and looks like a glistening goddess dressed in baggy jeans with gold glitter, a gold bustier and matching gold heels, posing for a second round of photos as a fan blows her wavy locks and her entourage hypes her up. This time, she’s serving sultry looks to Doja Cat’s “Agora Hills.” In the far corner, her mother, Gabriela Rueda, gets emotional as she sees her daughter in action, and with tears rolling down her cheeks, she softly tells me she remembers doing photo shoots for Emilia in the living room and her father holding the fan to blow her hair.

“I love to show the ‘Emilia Pop Star’ and get into character,” Emilia says with a smile. “I grew up watching pop divas who do that onstage and it’s like playing for a while for me. But I’m also the Emilia who comes from Nogoyá, who gets together to drink mate with friends, who has problems like everyone else, who cries because I’m very sensitive. I’ve always been firm. I’m very positive too. I’ve always had a very objective and optimistic character and personality. I think that’s what also helped me to be where I am today and achieve everything I’ve achieved.”

It’s an early evening in late September, and San Francisco is gleaming. The back patio at EMPIRE’s recording studios near the city’s Mission District is all white marble, reflecting the last rays of the setting sun as dozens of YouTube executives mill about, holding mixed drinks and picking at passed trays of beef skewers, falafel, lamb dumplings, and ham and chicken croquettes. At the moment, the companies’ top executives — EMPIRE founder and CEO Ghazi, COO Nima Etminan and president Tina Davis, as well as YouTube global head of music Lyor Cohen, among others — are sequestered in the studio’s live room for a quarterly business review, discussing the platform’s new tools, the label’s upcoming projects and how the two can best work together. A cake is adorned with YouTube’s latest milestone: 100 million members of its music subscription service.

Inside, the aesthetic is flipped: Black walls, dark wood floors and a black marble bar set the tone, while a projection screen in the main lounge area shows photos of Nigerian superstar and recent EMPIRE signee Tiwa Savage, who is in town finishing her new album. As Ghazi, Cohen and the others wrap their meeting and begin to filter into the party, everyone is ushered inside to hear her play some of her new music.

Trending on Billboard

“This is my first project at EMPIRE, and it’s really emotional for me because I’ve never had a label be this invested; most labels are not in the studio with you from morning until night,” Savage says before introducing her first single from the album, “Forgiveness,” which she will release a couple of weeks later. “They made me feel so welcome. I’ve been signed several times, but I’ve never been in a situation where it felt like home.”

The next day, at a barbecue restaurant near the studio, Ghazi is reflecting on the event — and what the connection with YouTube’s Cohen means to him. “I used an analogy with Lyor: ‘This is not a full-circle moment; this is the Olympic rings of full-circle moments,’ ” he says. “This brings so many circles of my life into place. I started as an engineer; I’m in a state-of-the-art studio that I could only dream about that I built with my bare hands. I used to listen to Run-D.M.C. — he found Run-D.M.C. The first tape I ever bought was Raising Hell — now I’m raising hell in the music business.” He laughs. “I prefer to call it ‘raising angels,’ but it’s cool. And then you have a giant like him in the record business that people used to blueprint their careers after, and now he’s telling me that he’s proud of the success I’ve had and that he watched me build a legacy. That’s validation.”

For Ghazi, 48, validation has seemingly been everywhere of late. The company that he founded in 2010 as a digital distributor for his friends in the Bay Area hip-hop scene has grown into one of the most formidable and powerful companies in the global music business. It has a record label, publishing and content divisions, a merchandise operation and 250 employees around the world, with a presence on six continents and deep connections to the local culture, politics and sports, including the Golden State Warriors and the San Francisco 49ers.

And now, as EMPIRE turns 15, it’s coming off its best year yet: For 19 nonconsecutive weeks, spanning from mid-July to the end of November, EMPIRE artist Shaboozey held the top slot on the Billboard Hot 100 with “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” tying the record for the chart’s longest-running No. 1 — an enviable achievement for any label, but particularly for an independent without any outside investment or corporate overlords. Shaboozey landed five nominations at the 2025 Grammy Awards, including best new artist and song of the year, redefining what is possible for an indie act and company in the modern music business.

Even more notably, that success arrived during a year when all three major labels experienced a painful and layoff-heavy molting process, reorganizing themselves to emphasize speed, technology, artist services and distribution — or, to put it another way, to try to look a lot more like EMPIRE. (“I think the battleship has been observing the speedboat for quite some time,” Ghazi says.) Amid those changes in the business, a new school of thought has emerged: that success is often found in cultural niches that gain mainstream acceptance from the bottom up, not the top down. Ghazi embodies that change: He may not have the mainstream name recognition of his peers in New York or L.A., but in his force of personality — humble yet emphatic, as many successful founders are — and his tireless, globe-trotting pace, he fits right in among the elite movers and shakers of the business.

“This industry used to be full of super-colorful entrepreneurs that were focused on their art, and when you talked to them, they had a certain excitement and shine in their eyes. Unfortunately, there’s not that many of them [left],” Cohen says about Ghazi. “I would call him one of the few. A person that is committed to excellence, cares about the details, shows up, has continuity and he’s positive and enthusiastic.”

Hermès coat and shirt

Austin Hargrave

There’s another reason why the YouTube party held such significance for Ghazi: The video streaming service is another company born, bred and based in the Bay Area that grew into a music industry behemoth after being built on tech foundations. Ghazi worked in Silicon Valley, including at an ad-supported video streaming service half a decade before YouTube, prior to dedicating his life to music, first as a recording engineer and then at digital distributor Ingrooves. He then founded EMPIRE — and sees his company as part of that lineage. “I’ve never met a music exec that has such a grip on the three verticals — creative, business and technology — and is fluent in all of it and active in all of it,” says Peter Kadin, a major-label veteran who is now executive vp of marketing at EMPIRE. “Someone who can go from meeting with an engineering team about building out the future of our systems, to sitting with finance and going through our deal structures with all the major DSPs [digital service providers], to going to the studio at night and mixing a Money Man album. There is no other executive doing that.”

Ghazi’s tech background and San Francisco’s reputation as the center of the tech industry are among the many reasons why he has always maintained that EMPIRE will never leave the Bay. The area has been part of him since he grew up in San Francisco’s Potrero Hill neighborhood, during his days at San Francisco State, throughout his time in the trenches of the local hip-hop scene and even now, when he has the ear of the new mayor of San Francisco, Daniel Lurie, whom he’s advising on cultural matters, and is working hand in hand with the NBA and the Golden State Warriors to produce events and release projects surrounding the upcoming NBA All-Star Weekend, which will be held in the Bay Area in February for the first time in 25 years.

But for a city that has had its share of big music moments and in which several major companies got their start, San Francisco’s music, and music tech, scenes have receded over the last two decades, with many companies lured away by the brighter lights and easier connections that exist in New York or Los Angeles. It’s a fate Ghazi is determined to avoid for EMPIRE — and a trend he’s actively working to reverse.

Ghazi likes to tell a story about when he was in his 20s in the early 2000s and mixed The Game’s first mixtape at San Francisco’s Hyde Street Studios. The project, which came out in 2004, ultimately helped Game get signed to Dr. Dre’s Aftermath Records, and when Dre and one of his executives heard the tape, they wondered who had mixed it because it sounded much more professional than the typical lo-fi promotional tapes making the rounds among underground hip-hop heads at the time. The guys invited Ghazi down to L.A. and encouraged him to move to the city and start working with them.

“I was flattered by it, but I was also furious — mad that I had to leave the Bay to build a music career,” he recalls. “I remember driving past the Capitol Tower like, people drive past this building and think, ‘I’m going to work there one day.’ And we don’t have that in the Bay. And I was like, ‘That sucks! I’m going to figure this s–t out!’

“It took me a long time — a really long time — but I figured it out.”

Prada coat, shirt, pants and shoes.

Austin Hargrave

“This might be the most mellow day I’ve had in three months.”

A few weeks later, Ghazi is driving through the streets of San Francisco, giving the signature tour of the city that he offers to anyone new in town — or anyone who may have only heard of its downtown blight and violence as depicted by the national news. It’s another beautiful fall day in the Bay, the first vintage weather after an extended heat wave, and he has cleared his schedule for the afternoon. For the next four hours, he unspools the history of the city neighborhood by neighborhood, street by street.

From the EMPIRE office in the Financial District, he drives into Chinatown, then to the Marina District and the picturesque Palace of Fine Arts. After that it’s into the Presidio, where Lucasfilm is headquartered, then over the Golden Gate Bridge into Sausalito, stopping at an overlook for a view of the city. Then it’s back across the bridge into San Francisco, along Baker Beach into Sea Cliff and then Richmond District, the neighborhood where Ghazi lived in a 350-square-foot apartment when he was first dreaming up what would become EMPIRE. (“I had like four f–king jobs,” he says. “Some of the happiest times of my life, though. Some of the most stressful, but some of the happiest.”)

Along the way — passing through Lands End lookout point, Golden Gate Park, the Haight-Ashbury district and Billionaires’ Row, down the famously crooked Lombard Street and into the Mission — he calls out the landmarks of his life: the apartment where he was born, his first recording studio, the place he got his first boba milk tea, the theater where he used to watch movies for two dollars, the Haight storefront where he once co-owned a clothing store, the place where he and Etminan built the wiring for the first EMPIRE office through a hole in the wall. After a few hours, he parks near the water and gets out of the car to take it all in.

“They say San Francisco’s a doom loop,” he says, looking across McCovey Cove into Oracle Park, home of the San Francisco Giants, in the late-afternoon sun. “This look like a doom loop to you?”

Louis Vuitton sunglasses and jacket

Austin Hargrave

San Francisco is personal to Ghazi in a way that goes deeper than the typical nostalgia people feel for home. And the recent right-wing news coverage by 24/7 cable networks — which has portrayed the city as crime-ridden and drug-addled, overrun by a persistent homelessness problem that the city has not been able to handle — that has proliferated in recent years has spurred him and other music leaders in the city into action.

“San Francisco had such a heyday up until the pandemic, and it’s been really hard to watch the world s–t on our city,” says Bryan Duquette, founder of Another Planet Management and a member of the core executive team at Another Planet Entertainment, the San Francisco-based independent promoter that puts on the Outside Lands music festival and operates Bay Area venues including Berkeley’s Greek Theatre and San Francisco’s Bill Graham Civic Auditorium. Duquette, who has lived in the Bay for over 20 years, met Ghazi in 2023 and found a kindred spirit determined to rectify the negative perceptions held by outsiders. Last year, Another Planet teamed with Ghazi, EMPIRE and artist management company Brilliant Corners to assemble 100 members of the Bay Area music scene to meet with Lurie, then a mayoral candidate, to discuss his plan to reinvest in the artistic community. “Daniel really was trying to get to the people who were creating culture and helping the city become, again, what it was seen as globally,” Duquette says. “And Ghazi is a really big piece of that.”

Lurie’s outreach ultimately won him much of the creative community’s support, and in turn helped win him the election; he was sworn in as the 46th mayor of San Francisco in January. “The arts and culture have always defined us, and I firmly believe that EMPIRE and Ghazi are going to be part of the revitalization of our city,” Lurie says. “He knows what’s going on in the music world better than just about anybody, and I’ll be listening carefully to his guidance and his counsel.”

San Francisco Mayor Daniel Lurie and Ghazi in 2025.

Courtesy of EMPIRE

EMPIRE’s fierce independence, too, is an expression of the Bay’s ethos. “He’s a representative of the independent grind and the culture here; that’s something that everyone in the Bay can resonate with, just coming from the ground up and being the underdog,” says P-Lo, the Bay Area rapper who has been with EMPIRE since 2017. (P-Lo is spearheading a project with the Golden State Warriors’ content division, Golden State Entertainment, that will be released ahead of NBA All-Star Week and distributed by EMPIRE and will feature more than a dozen Bay Area artists.)

But that independence, and particularly the eye-opening success that EMPIRE has experienced over the past few years, has also brought scrutiny — and tests of Ghazi’s commitment, particularly during a time of intense consolidation in the music business. When a media report circulated in November 2023 positing that LionTree was lining up a $1.5 billion bid to buy EMPIRE — “Most believe Ghazi is not a seller, but big checks have changed other people’s minds,” the report needled — Ghazi was furious and sent a staffwide email emphatically denying it, according to multiple employees. A week after EMPIRE’s YouTube event, he was even more publicly defiant, insisting while onstage in October at the industry conference Trapital Summit in Los Angeles: “I’m not for sale. Period. I am dead serious. I am living my purpose. There’s no price on that.”

It’s a frustrating topic for Ghazi, not least because it implies a fundamental misunderstanding of who he is and why he does what he does. “You don’t understand — I just don’t care about money,” he says. “It’s not my motivation.” Instead he talks about the principles instilled in him by his father, a Palestinian refugee who brought his family to America to put them in a position to control their own paths if they were willing to work for it. “I don’t see myself ever working for somebody else,” Ghazi continues. “I’d rather retire. There’s no price for my autonomy. It’s the greatest gift to a leader.”

Still, his insistence on sole ownership — and the sheer force of personality that he exudes in binding the company together — has left enough of an opening for industry analysts to wonder about succession planning, about what might happen to the company when, or if, Ghazi decides to hang it up. He freely admits he won’t stick around as a hands-on CEO forever, but also that EMPIRE is about legacy for him and that he values legacy and autonomy — the freedom to chart his destiny — more than anything else. In that sense, he’ll never truly leave EMPIRE, even as the rumor mill keeps churning. “I always admired athletes who retired when they were on top. I want to be at the top of my executive game when I quit,” he says. “I don’t want to be the guy who hung on for too long. I’m already the owner, so I could still hang around as a chairman, but I don’t need to hang around as the guy running s–t day to day.”

Austin Hargrave

But that’s not happening anytime soon. In the past six months alone, EMPIRE has expanded into Australia, East Asia and South Africa and completed the acquisition of Top Drawer Merch to bring another monetization vertical into the fold for its artists. Ghazi is engaged in the industrywide debates surrounding superfandom revenue and is constantly seeking new opportunities; the two weeks prior to this driving tour, he had been in Tokyo, Seoul, Beijing, Cambodia, Singapore, Bali, San Francisco, Paris, Marrakesh, Singapore again, Seoul again, Las Vegas, Seattle and back to San Francisco: taking label meetings, shooting music videos, meeting with DSP partners, attending conferences and awards shows and directing work on the EMPIRE studios here, with the goal of expanding the company’s reach step by step — taking the stairs rather than the elevator, as he puts it.

“The goal is to be in all the places that make sense for us culturally,” he says. “Is the music interesting? Is the culture interesting? Holistically, how does it play with our DNA? What’s the cost of acquisition and retention? Do I like the music here? But the initial fuel is the passion; then, from there, start to figure it out.”

Joice Street is mobbed. The Nob Hill alley, around the corner from the Bruce Lee mural that adorns the wall next to the Chinese Historical Society of America Museum, is the location this afternoon for P-Lo’s “Player’s Holiday ’25” video shoot, and dozens of people, including some of the Bay’s biggest rappers — Saweetie, G-Eazy and Larry June among them — are filming on a basketball court on the roof of a building overlooking the city. Ghazi is there, not just because EMPIRE is distributing the song, which will appear on P-Lo’s album with Golden State Entertainment, but because he’s scheduled to make a cameo in the video.

Ghazi spends more than an hour on the rooftop, where he seemingly knows everyone — and everyone wants a minute of his time. But soon he heads back to the studio to return to work. The vibe there is low-key, but a typical cross section of artists and creatives are at work: Nai Barghouti, an Israeli-born Palestinian singer, flautist and composer, is in Studio C, working on songs for her new album before heading back out on tour; two producers from dance label dirtybird, which EMPIRE acquired in 2022, are in the live room, “ideating the next big hit of 2025”; a regional Mexican group sits on the patio outside, figuring out songs on a guitar; YS Baby from EMPIRE-owned viral content aggregator HoodClips (which has over 11 million followers) is talking about the podcasts he has lined up. Later, Japanese rapper-singer Yuki Chiba — whose 2024 collaboration with Megan Thee Stallion, “Mamushi,” reached No. 36 on the Hot 100 — takes over Studio A, where he plays a slew of songs slated for upcoming projects and discusses rollout plans.

EMPIRE may have gotten its start in Bay Area hip-hop and made waves on the front lines of West African Afrobeats, but these days it embodies the global outlook that Ghazi always envisioned; Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” after all, is a country crossover hit out of Nashville that reached No. 1 in 10 countries. EMPIRE partnered with Nashville-based indie promotion company Magnolia Music to handle its country radio campaign, and from there the single branched out to other formats, ultimately becoming the first song in history to go top 10 on four different Billboard airplay charts: country, top 40, adult top 40 and rhythmic. And Ghazi sees himself as a global citizen helping people around the world — “creating microeconomies” within the territories EMPIRE operates, he says — not just within the confines of the Bay Area.

Shaboozey and Ghazi at the 2024 CMA After Party.

Becca Mitchell

He is also the highest-profile Palestinian executive in the music business and has openly condemned the humanitarian crisis that has erupted during Israel’s war in Gaza. His Instagram profile picture is the Palestinian flag; he regularly shares videos and photos decrying the violence against civilians; he helped facilitate the remix to Macklemore’s track dedicated to Palestine, “Hind’s Hall,” and went to Seattle in October to support the rapper at a Palestinian benefit concert, despite Macklemore not being an EMPIRE artist. He stresses that he does this on a personal level, explicitly not to politicize the company. When asked if he feels a responsibility of sorts, given his profile, to help raise awareness about that humanitarian crisis, he simply says, “I feel like I want to be proud of the man in the mirror.” (“He’s Palestinian and I’m Israeli; we shared our great pain and anxiety over what’s happening in the Middle East,” says Cohen, who also calls Ghazi “a genuinely good guy.”)

But despite its global activities, EMPIRE has stayed focused on its local roots — and is continuing to strengthen them, too. In 2020, it started putting on the cultural festival 415 Day (which takes its name from a San Francisco area code) and has gotten further into live events through its deepening relationship with Another Planet. The San Francisco studio has become not just the creative center of EMPIRE’s operations but also an event venue for the city’s music and civic communities. And in a massive move in January, EMPIRE purchased the 100,000-square-foot historic Financial District building One Montgomery, built in 1908, for $24.5 million, according to The San Francisco Business Times; Ghazi plans to move the company headquarters there after renovating it. Eventually, One Montgomery could become the San Francisco version of the Capitol Tower that Ghazi envisioned all those years ago.

“There have been so many times that people have told him he couldn’t do something, and then he was able to do it, that it gave him all the fire and was the catalyst for him to be the person he is today,” says Moody Jones, GM of EMPIRE Dance, who has been with the company since 2018. “They told him he was crazy to have a music company in San Francisco; that he would never compete with a major; that he would never get out of hip-hop; that he would never open up a studio. They told him San Francisco would never be cool again. And every single time he was able to show them that, ‘No, I’m right.’ ”

That all builds into the larger cultural role Ghazi is playing in his city and beyond. Lurie just announced the inaugural San Francisco Music Week, a celebration of the city’s local music industry culminating in an industry summit with a keynote conversation with Ghazi. And while he says he’s not interested in San Francisco politics, he wants to be consulted from an advisory perspective on cultural events in the city and try to bring in more events beyond just music — Art Basel San Francisco is one that he has begun to advise on, though that project is currently on pause. He has worked with the city and the NBA on a slew of events around NBA All-Star Week and discusses the Super Bowl and World Cup in 2026 as further opportunities to showcase all that San Francisco has to offer. “For events like the NBA All-Star Game, Super Bowl LX, the World Cup, we get to show off all the greatness here, and Ghazi and EMPIRE and the artists they represent are part and parcel to what makes San Francisco so great,” Lurie says. “We need more Ghazis.”

Ahead of All-Star Week, he has made a series of moves and partnerships with the NBA and the Golden State Warriors, including with the game NBA 2K25, with which EMPIRE partnered for a first-of-its-kind deal that includes a limited-edition vinyl box set with 13 tracks by EMPIRE artists; EMPIRE artists on the game soundtrack; and Ghazi and some of EMPIRE’s artists scanned into the game itself. At the studio in September, he sat for an interview with NBA 2KTV host Alexis Morgan — who, to Ghazi’s delight, is also from the Bay Area — that will be part of NBA 2K25’s bonus features.

Ghazi (right) with NBA 2KTV’s Alexis Morgan.

Courtesy of 2K

But ultimately, it is all about the music. Shaboozey’s career is now in a superstar arc, and “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” will soon become EMPIRE’s fifth record with more than 10 million equivalent units in the United States according to Luminate, with over 1 billion on-demand streams. A few years ago, EMPIRE was flying largely under the radar, but Ghazi now has it at the top of its game, with a track record that speaks volumes in an industry based just as much on history as on what’s coming next.

“You always learn, all the time; you’re always adapting to what’s going on around you,” he says. “And sometimes you can’t believe how far you’ve come. But that only inspires you to go further.”

This story appears in the Feb. 8, 2025, issue of Billboard.

It’s an early evening in late September, and San Francisco is gleaming. The back patio at EMPIRE’s recording studios near the city’s Mission District is all white marble, reflecting the last rays of the setting sun as dozens of YouTube executives mill about, holding mixed drinks and picking at passed trays of beef skewers, falafel, […]

As the clock strikes 10 on a chilly January night in Atlanta, Travis Scott, the King of Rage, is preparing to unleash a performance that will take his career to new heights — literally. Scott has already notched a dizzying number of accomplishments for a modern hip-hop star: four No. 1 albums on the Billboard 200, the highest-grossing tour ever by a solo rap act, the first rapper to sell out Los Angeles’ SoFi Stadium. But tonight, perched on the roof of Mercedes-Benz Stadium and not much more than 10 feet from its edge, he’s dreaming even bigger.

As his latest song, “4X4” — which became his fifth Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 when it debuted atop the chart in early February — pulsates through the speakers, La Flame rubs his hands together before launching into the pretape of his halftime performance for the College Football Playoff National Championship. At the cue of video director Gibson Hazard, rap’s ultimate daredevil bounces around fearlessly, savoring the thrill and danger of the moment.

Trending on Billboard

The 33-year-old native Houstonian, who was once a ball boy for the NBA’s Houston Rockets, has love for his hometown’s sports culture — and its accompanying theatrics — that runs as deep as his passion for its unique strain of Southern hip-hop. As a teen sitting in his grandfather’s kitchen, he watched the nail-biter 14-inning game-three battle between his beloved Houston Astros and the Chicago White Sox in the 2005 World Series from his grandfather’s kitchen (the Astros lost that game, and the series in four). He recalls witnessing Rockets legend Tracy McGrady’s jaw-dropping 13 points in 33 seconds against the San Antonio Spurs in 2004. Scott’s own unyielding spirit for captivating audiences on the biggest stages was born in these historic sports moments. “I was a ball boy for the Rockets when T-Mac was about to leave [the team in the late 2000s] and he was kind of fizzling out,” Scott remembers as he scarfs down a Domino’s pizza slice the day after recording his fiery performance. “I always wanted him to win.”

While Scott may no longer be chasing rebounds inside Houston’s Toyota Center, his bond with sports is stronger than ever, fueled by his competitive streak and relentless drive to be as legendary as his superstar athlete friends Tom Brady and James Harden. “12 is one of my favorites,” Scott says, referencing Brady’s former jersey number. “I go to him when it comes to achieving the highest level of greatness. I have a couple of people I can name [when I need advice], but 12 is somebody I can turn to when it comes to that because time and time again, when it comes to having to go and get it, I’ve seen him do it.”

Over the last couple of years, Scott has mounted the type of high-stakes comeback that might make a Hall of Fame athlete take notice. In October 2021, a deadly crowd surge killed 10 people at his Astroworld Festival in Houston, throwing the decorated rapper’s career into jeopardy. After numerous lawsuits were filed against Scott, a grand jury declined to indict him on criminal charges; the families of the 10 victims reached settlements with him and Live Nation. But in 2023, as a dark cloud still loomed over him, Scott returned. His album Utopia, delivered that July, debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 with an impressive 496,000 album-equivalent units, according to Luminate, and landed 19 songs on the Billboard Hot 100. And the star-laden album featuring Beyoncé, Drake, SZA and The Weeknd wasn’t just a blockbuster hit — it catalyzed Scott’s post-Astroworld comeback.

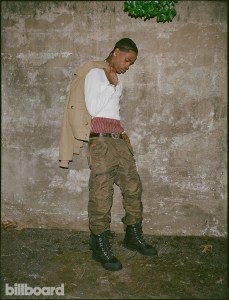

Martine Rose top, jacket and pants; Oakley boots.

Gunner Stahl

That October, Scott launched his Circus Maximus Tour, an interactive spectacle where he let his imagination run free. He created an amusement park-like atmosphere where he invited fans onstage to get on actual rides (“Amusement parks, to me, are the illest things ever,” he says), and his fire-breathing performances showcased the same audacity that made him the poster child for rage rap when he first rose to fame in the mid-2010s.

It wasn’t just the biggest tour of Scott’s career: With $209.3 million grossed from 1.7 million tickets sold, according to Billboard Boxscore, the 76-date trek became the highest-selling outing ever by a solo rapper. Stateside, Scott played mostly arenas — save New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium and his history-making SoFi Stadium gig — but his overseas fan base propelled him to stadiums in South America, Oceania and Europe, where he performed massive shows in cities including London, Milan and Cologne, Germany, selling more than 71,000 tickets at the lattermost. Scott and his longtime manager, David Stromberg, say they want to conquer the Asian touring market next.

“It’s always a challenge to create a new chapter of what the live shows look like,” says Stromberg, who has worked with Scott for over 10 years. “We thought that the [2018-19] Astroworld Tour was our highest peak. We were in arenas and now we’re in stadiums.” In April, Scott — who was slated to headline Coachella in April 2020 before the pandemic forced the festival’s cancellation — will appear for a performance there billed as “designing the desert.” And, Stromberg says, “With Coachella coming up, we need to figure out a new chapter.”

While Scott’s disruptive spirit has propelled him to chart and touring glory, his savvy on the branding front has drawn attention from a variety of major companies. Brands such as Nike, McDonald’s, Audemars Piguet and Epic Games have launched significant partnerships with Cactus Jack, Scott’s label and lifestyle boutique. Athletes like Aaron Judge, Jayson Tatum and Jayden Daniels have sported Scott’s Nike sneaker line. And last July, Scott got the ultimate sports co-sign when Michael Jordan wore a pair of unreleased Travis Scott x Air Jordan sneakers to the beach. After watching Cactus Jack flourish, Fanatics CEO Michael Rubin partnered with Scott, popular retro sports brand Mitchell & Ness and Lids to launch a merch line called Jack Goes Back to College featuring a range of college-themed apparel and accessories.

“Normally, someone will come to work with us, give feedback and we’ll do all the work,” Rubin says. “With Travis, it’s 100% driven by him, and that’s because he knows his fans and the market, and he has such a strong feel for what the market wants. [When we collaborated], he completely designed the products 100% on his own. He has such great vision and product skills that I’ve never seen before.

“I’ve seen so many people in this world, but the fandom and loyalty he has from his fans is truly extraordinary,” Rubin continues. “Someone could offer him a billion dollars, and if it’s not brand-right and he doesn’t feel it’s right for his customers, he will not do it. That’s why he’s so careful about everything that he does. He wants to make sure it’s the right product and the right vision. Travis may be the most authentic person I know. He’ll never sell out.”

Gunner Stahl

Scott and Rubin promoted the Jack Goes Back to College line with a 36-hour college campus tour, making stops at Louisiana State University, the University of Southern California and the University of Texas, where they spoke to the schools’ athletic teams and even worked behind campus bookstore registers to sell their products. Throughout, Scott was everywhere — giving motivational speeches, showing up for an impromptu performance (at LSU local bar Friends) and joining football practice at UT, where he even helped with punt returns. And he’s eager to do all that again and more.

“When I was talking to Trav at the National Championship game [this year], he was like, ‘All right, what four schools are we doing next year? We’re out. We did three last year; we’re doing four next year,’ ” Rubin says.

His passion goes beyond the gridiron: Two decades after watching the Astros in the World Series, he’ll host current Astros players — and a slew of other current and former baseball and football greats, along with music stars like Metro Boomin, Teyana Taylor and Swae Lee — at the Cactus Jack Foundation’s HBCU Celebrity Softball Classic in Houston on Feb. 13.

Though Scott was largely consumed with touring and further building Cactus Jack over the past year, he returned his focus to music last August, when he released his acclaimed second mixtape, 2014’s Days Before Rodeo, to streaming platforms. Initially a free download — and a steppingstone in Scott’s career — the project bowed at No. 2 on the Billboard 200 with 361,000 album-equivalent units, falling 1,000 units short of Sabrina Carpenter’s Short n’ Sweet. A month later, Days Before Rodeo rocketed to No. 1 after Scott offered vinyl editions of the project online, securing him the fourth No. 1 album of his career.

“When I was coming up, people always looked at me [strangely],” Scott says. “I don’t know. I’d always hear a little s–t of ‘Is it rap? Is it this? Is it just a vibe?’ I’m pushing hip-hop. It’s 50 years old but still has time to stretch. I feel like, ‘OK, I’m leading the new charge of what the next 50 years of this s–t is going to be like.’ ”

Prada top, jacket, pants and shoes; Oakley sunglasses; Eliantte jewelry.

Gunner Stahl

Like sports, music is ultracompetitive. How do you stay at the top of your game?

A lot of people say I’m at the top of my game all the time, but I’m still striving to get to that point. I could see it in spurts or moments like, “Oh, this is ill!” It’s like a full 360 universe I’m trying to connect, but I’m always inspired, and I think that’s what keeps me motivated — not just content. I’m always working toward the next thing. It’s not like in a bad way where you don’t sit and enjoy, but I always want to push the limits. I feel like there’s always been random lulls that come my way that try to suppress the sound, and I feel like I’ve always been trying to take one foot forward every day to break down those barriers.

I feel like you’re the Stephen Curry of rap because you revolutionized hip-hop and broke boundaries for the new generation, sort of like how Steph changed the game with the three-point shot. Can you see that?

Yeah. I probably wouldn’t have said it out loud or anything like that. I like to believe the things I’m doing are pushing music and where things can go. With Steph, he changed the game in a wild way. Whether it’s good or bad, everyone’s shooting from half-court and s–t, which is dope as f–k. It’s just revolutionizing the game and showing there’s no limits to what you can do as a player. Having the lines, literally, lines saying this is the limit and [saying], “Nah, f–k it. I’m shooting from [half-court]. I’m going to do what I have to do to get this W.” And not being content — you see, he works on his craft every day. I don’t think anyone’s ever going to catch [his] three-point record, and he’s still working on his craft. “How can I evolve? How can I get better as I’m getting older?” It’s dope.

You partnered with the WWE and escorted Jey Uso at L.A.’s Intuit Dome during Monday Night Raw on Netflix. What was that experience like?

The energy out there was crazy. I was telling [Superstar] Triple H, “This s–t is wild.” For my shows, I try to create that maximum energy level and have [the audience] feel like they could reach their highest level of ecstasy — the feeling of being happy and free. Not to sound so trippy, just see that enjoyment. When I’m performing, it’s the energy of what a hardcore match can be. [Popular WWE-style match] Money in the Bank — ladders, tables and chairs — anything. It’s like, “Ah, this s–t is ill.” I can’t wait for this year [to get in the ring]. I’m training to get ready for this. It’s going to be some dope s–t.

Gunner Stahl

If you do get in the ring, who’s your first opponent?

I’m going to leave that under wraps right now. I’m a little bit more of a mystery. I might pop up and start tearing s–t up. I’m more of a “Let me get into that hardcore s–t [type of guy].” It’s heavy. [WWE Superstar] Mick Foley-type heavy. You never know where you about to go lay some smack on a motherf–ker. I might pop out and start some s–t.

How has your brand, Cactus Jack, become so dominant?

We try to be ourselves and be organic. I’m still a fan of fandom. [I have] that sort of understanding [that] it’s not just me — got my guys Don [Toliver], Sheck [Wes], Bizzle [Chase B]. You know, all of us who make it a whole family. Organically, just being us and creating those experiences, that’s what I love to do. Whether I’m collaborating with someone or working with someone and trying to push design, it goes hand in hand, [whether we’re] tailoring beats or tailoring clothes.

On your college tour, you visited three different campuses in 36 hours. What is it about the college energy that you enjoy the most?

When I was in college [at the University of Texas at San Antonio], it was lit, and it’s still lit. I feel like every kid should go to college whether you’re trying to do the books or not, just for the experience: the [socializing], community and just riding for something [is great]. School pride is amazing. You go to these games and see 100,000 people in the same color cheering loud for the people that’s repping. It’s just lit.

You’ve said you want to go to Harvard University and possibly study architecture. Is that still something you hope to pursue?

It’s crazy. The construction game is the most frustrating thing in the world. Me traveling, seeing modernism, different houses, structures and things, when you go to different countries and see how people create a structural design with literally nothing, people can put up structural places in shorter times than we do in the U.S. And even just creating things from scratch, the engineering and planning of things takes forever. I just got a true passion for it and I always want to create, so I need to learn this s–t. I’ve always wanted to learn just the engineering part and technical aspects of it. I can draw ideas and create 3D renderings all day, but how do I physically get this to work and put it together? It’s a tedious process.

You and Michael Rubin have a good relationship. How has he helped you push the Cactus Jack brand forward?

I watch how he runs a multibillion-dollar empire and try to be hands-on as much as possible. Just be active. The call-and-response. Get to it on an everyday basis. To be able to run something on that level, you have to go hard at it, through the good and the bad. You could have problems, but it’s how you respond — just trying to stay connected. You could be the higher-up, disconnected and have people run it for you. Try to be as hands-on as you can and as multifaceted as you can. I apply that to what I got going on.

Gunner Stahl

How do you maintain high intensity and inspiration as you spread that energy into different areas, like music and merch?

It all goes hand in hand. Since day one, I’ve had that mindset. The key to it all is having a solid team and people understanding what you’re trying to achieve. They connect with you and have that same drive. Every day is a new day, but as you get through it, you learn so many things. I’ve been in this for a minute and think as we grow, we learn so much s–t. I try to stay firm on it. Remind people what we’re trying to work toward and this is what we have to achieve. It’s not easy. If I can be up early, we all can. Just having that discipline. I just got a good support system. [Without them], I’d be f–king drowning out here.

Your 7-year-old daughter Stormi’s favorite song is Days Before Rodeo’s “Mamacita.” How does it feel to see not only her but also younger fans appreciate your older work like that and your debut mixtape, 2013’s Owl Pharaoh?

I love it, man. F–k! I still listen to that album, too. It just reassures me that I’m not f–king crazy. This s–t hard. That’s how I know that Stormi’s turnt. Out of all the songs, that song’s turnt and she loves it. Her new favorite song is now “Thank God.” I don’t know if it’s because she’s on it. She didn’t know she was on it until she heard the album. She’s like, “That’s me!” She knows every word. It’s cool to see even the youth is tapped in on that level. It’s ill. It gives me a reason to wake up.

Your debut album, Rodeo, turns 10 this year. Do you have special memories from that era?

I do. I got a lot. Rodeo is lit. The only thing I wish from that album, and I probably should do for the 10-year anniversary, is that the action figure would come out on a USB and not a CD. That’s the main thing and it never happened. That album creation was everything for me: touring, working on the album and being at Mike Dean’s crib all day. Rest in peace, Meeboob [Dean’s late dog]. Man, we love that dog. It was lit, man.

What has been your own biggest championship moment in your career?

When I was walking through SoFi and had my little ones with me, they got on the stage. I remember my [3-year-old] son, [Aire] — he can talk — he was like, “Yo, who’s performing here?” My daughter was like, “Daddy!” My son was like, “All these people.” I’m like, “Yeah, it’s going to be kind of turnt.” He’s like, “For real?” Stormi’s like, “Yeah.” She’s like describing the show. There’s all this pyro and people are going crazy. I was like, “Yeah, this is tight.” I always wanted to do stadiums, and it was kind of cool to have the little ones understand and know what I’m doing. They were amped for the show. So that was lit.

How do you define greatness at this point in your career?

I think it’s the ability to wake up and still go hard at this. Still have the drive to go hard and not give up on what you set out to do from the beginning. That’s greatness for me. Achieving that level no matter how many times you could be shunned from a Grammy or whatever the f–k could happen. It’s waking up every day to be like, “There’s still somebody out there listening and somebody that cares.” Let’s go hard for that and yourself. I really care about that — it keeps me going.

You had your Super Bowl moment in 2019, performing with Maroon 5 at halftime, but that wasn’t a full-fledged Travis Scott production. Is that still on your bucket list?

Hell yeah, man. Yeah, tell the [NFL] to hit me up. They know who to call. Word.

Gunner Stahl

Where are you heading musically on your next album?

I want to say the title right now, but people aren’t going to understand it. I have some more tweaking to do.

Fair. But where are you going sonically?

I feel like for Utopia, I was striving to push things to a high level. I’m still reaching for that. I’ve been having so much fun with music and s–t that I think it’s cool to be artistic and have fun with it. I’ve been producing more, making a lot of the album, and going in on that level is making it more exciting. I can’t wait, actually.

At this point in your career, is there anyone left that you want to get into the studio with?

Yeah, it’s this band called Khruangbin I want to work with. This might be crazy, but I would love to get Taylor Swift or Sabrina Carpenter on a hook.

Why Taylor or Sabrina?

Because I have some ill ideas.

You and Carpenter were going head-to-head last year on the charts when her album beat Days Before Rodeo in its opening week.

Charts, shmarts, man. Who measures that? Her album’s cool. Days Before Rodeo is 10 years old. It all works.

With everything you’ve been through over the last few years to now having the biggest tour ever for a solo rap artist, do you feel vindicated that your fans still support you?

I love the fans and I’m appreciative, but I’m still striving to prove what I’m here to do, what I mean and what I stand for, especially when it comes to performing. To the fans, I feel like a lot of times, because I don’t do a lot of interviews or talk a lot, Travis Scott can be misunderstood. What I care for can get misunderstood. But every day, I’m going to strive to show that greatness.

This story appears in the Feb. 8, 2025, issue of Billboard.

As the clock strikes 10 on a chilly January night in Atlanta, Travis Scott, the King of Rage, is preparing to unleash a performance that will take his career to new heights — literally. Scott has already notched a dizzying number of accomplishments for a modern hip-hop star: four No. 1 albums on the Billboard 200, the […]

Kai Cenat — the eternally upbeat streamer whose profile has exploded in recent years to make him the most popular personality on the Amazon-owned Twitch platform — is taking a moment to think.

In the five years or so since he’s become a full-time content creator, Cenat has had some of the most famous hip-hop artists, athletes and actors come to his house to drop in and join the “chat,” the affectionate word he uses for any of the 700,000-plus people who subscribe to his channel. He’s thinking over whether he can recall a favorite moment among so many, but it’s tough. It wasn’t when SZA and Lizzo stopped by together in the fall, nor when NBA All-Star Kyrie Irving taught Cenat’s friends and family how to play basketball. It would be reasonable to think it might be one of the many times Kevin Hart, one of his idols, swung by to kick it during the holidays.

Sitting in the basement room of his mountainside Georgia mansion, the 23-year-old needs a beat or two to consider the options. The room is a temple of adolescence, with pictures of his favorite basketball players, vintage arcade machines like Pac-Man and a gaming racing wheel. He has a huge walk-in closet and a king-size bed, both of which are being used by his three-person styling team. The only part of the room that hints at some sort of professional living there is the desk at one end that contains the computer and camera setup that power his streaming empire. Dressed in a BAPE hoodie and stonewashed denim that make him look like he’s straddling sartorial eras, Cenat finally settles on an answer: The May weekend last year when Drake and Kendrick Lamar dropped a total of four songs, three of them back to back.

Trending on Billboard

“That was the most fun experience I’ve had,” he says with a smile bright enough to power a Tesla. “I’m not going to lie.” It’s tough to tell if he’s actually super excited or just trying to manage his constant and unbridled childlike energy.

“We never experienced something like that,” he explains. “It was a good week. Everybody had their opinions. I was literally hopping on stream and had like 60,000 viewers. As soon as they dropped, my s–t was spiked to like 100,000.”

When it came to the beef that ended up taking over hip-hop for the better part of 2024, most popular streamers took sides or called winners, and Cenat was no different. “I’m cool with Drake,” he says. “So people would expect me to be on Drake’s side.

“But I’m not going to lie,” he continues. “Kendrick won that battle. It was good. I loved every second of it. I was just appreciating the moment. Like, bro, we got bangers right now that’s dropping back to back and everybody’s talking about them. It was definitely fire.”

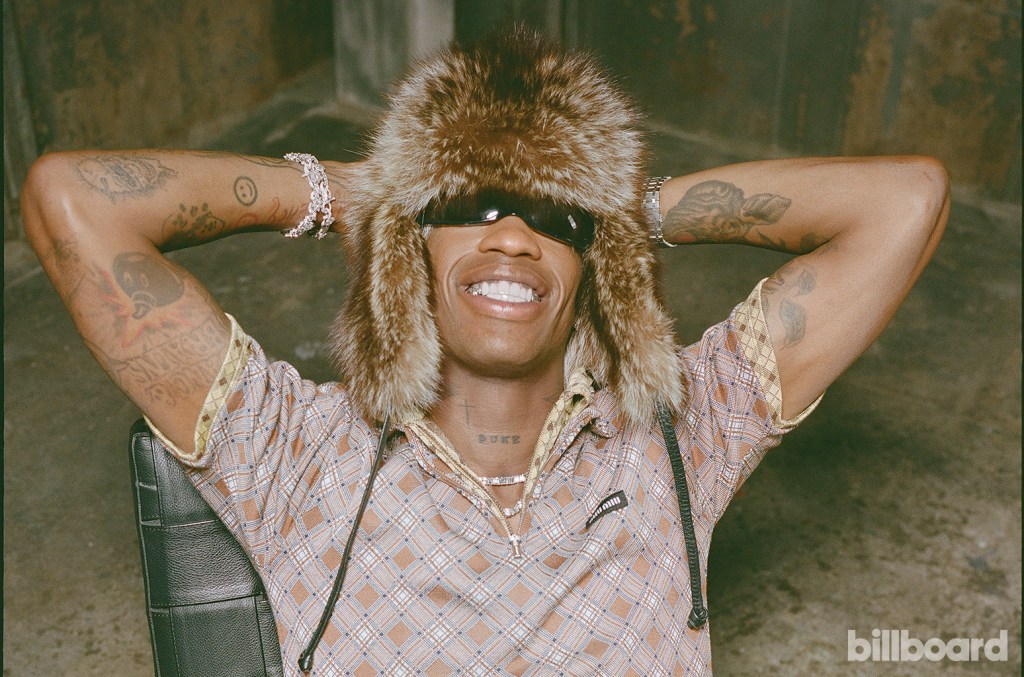

Kody Phillips top, Louis Vuitton pants, AMIRI hat, Jacob & Co. watch.

Andrew Hetherington

For a person who makes a living by staring straight into a camera for hours on end and connecting with strangers, appearing truthful and genuine is crucial — and it’s one of Cenat’s superpowers. It’s what has allowed him to not only become the most popular streamer on Twitch, but also the most popular streamer in hip-hop and, arguably, one of the most powerful people in all music. No other streamer has been able to corral as many artists to be a part of their online world as Cenat has — and very few have earned the cultural respect from fans and artists that he has. His words hold so much weight that he’s able to materially affect the careers of the superstars his fans care about. That’s why during that weekend in May, Drake told Cenat to “stay on stream” before dropping his “Family Matters” dis track — he knew a good review from the jovial streamer would bode well for him not only in his sales, but in his battle with Lamar. But it’s also why, after the streamer said Drake’s “The Heart Part 6” was weak, Drake allegedly blocked him.

That’s just one of many major moments Cenat has driven for music’s biggest stars over the past few years. He’s had spats with Nicki Minaj, Blueface and Ye, though he eventually made up with all of them. (Minaj even gifted him a pink throne that he proudly keeps in his bedroom and doesn’t let anyone sit on.) Most recently, while on a stream in early January, he panned Lil Baby’s highly anticipated fourth album, WHAM, even questioning why certain songs were added to it. WHAM trended on X — mainly due to jokes about Lil Baby being washed. While it’s unfair to attribute to Cenat the initial negative reaction Baby’s album received on social media, he had a significant hand in spreading the sentiment that it wasn’t Baby’s best work. That’s just the power Cenat holds in 2025: He’s a self-made institution. Like EF Hutton, when Cenat talks, people listen.

All of that has made him, for all intents and purposes, the closest thing Gen Z has to 106th & Park or TRL, the erstwhile midday live-music shows that used to air on BET and MTV and were appointment viewing for any fans wanting updates on their favorite artists. Cenat’s stream is now the main place to tune in to see artists having fun and feeling comfortable enough to let loose and relax. “Yeah, people will be saying that,” he says with an impish grin. “For everyone to come to play music or just have a fun interaction, it means a lot to me, honestly, because I didn’t think, out of everybody, they would want to come over to my house. I still haven’t got to like really let it sit in and really let it digest, but it does mean a lot to me, and I’m just having fun as I go on.”

Building a platform to rival the biggest cable music stations of the 1990s and early 2000s should take at least a decade — but it’s important to understand how quickly all this has happened. Cenat, who first started posting on YouTube in 2019, is not an overnight success. But considering how integral he’s become to the cultural fabric, you could be forgiven for thinking he’s been ingrained in the hip-hop internet landscape forever.

Before first appearing on the platform, the Bronx-born creator had moved to Georgia at a young age with his mother and siblings, living in a homeless shelter while his mother worked multiple jobs to create a better life for them. It was tough, but Cenat says with his trademark positivity that he doesn’t remember those times as rough or bad. The family eventually made its way back to New York, and Cenat enrolled at SUNY Morrisville to study business administration. In search of a creative outlet, he started posting funny skits on YouTube. For Cenat, the decision was a no-brainer: “I watched YouTubers growing up — that’s why I understand it so well.”

Andrew Hetherington

Andrew Hetherington

Mainly filmed in his dorm room and around campus, Cenat’s skits were low-rent affairs with minimal costumes or production where he came off as a slapstick comedian in the tradition of Martin Lawrence. His most viewed videos were his challenges, like the popular “Try Not To Laugh Challenge” that he still does to this day and clips like the Extreme Ding Dong Ditch series, which sounds crazy but was just Cenat and his friends playing the childhood game in different locations. They didn’t get massive traction, but they caught the eye of fellow Bronx-bred creator Fanum, who invited Cenat to join the AMP (Any Means Possible) collective of YouTube creators. Soon, Cenat was posting videos at an increasingly rapid pace, as well as appearing in clips by other AMP members.

By 2021, Cenat was ready to branch out from YouTube and grow his audience another way. He decided to try livestreaming and landed on Twitch, the platform Amazon acquired in 2014, as his new home. At the time, it was being used mainly by gamers to livestream gameplay while avid fans watched like a professional sport. Cenat enjoyed playing video games, but his first foray onto Twitch was through what are known as “just chatting” streams, where he’d sit down with a camera on his desk and, yep, just talk with his audience. By the end of his first day on Twitch, he had 5,000 followers. By the end of his first month, he had 70,000. The next month, 140,000 people tuned in.

Despite Cenat’s brand now being so closely associated with hip-hop, he didn’t start producing music content, really, until he started streaming. “When I started streaming, most of my content was blowing up based off me just reacting to different songs and listening to albums when they drop and just enjoying it for what it was and just saying, like, my opinions on it,” he remembers. “And then, like, people just loved it.”

In fact, he didn’t even listen to rap until he was a teenager. Growing up, “I did straight Michael Jackson up until high school” — which is when Cenat became a fan of a hometown hero who was then dominating the charts: A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie. “That was my real transition,” he says. “I went from Michael Jackson to A Boogie, and I explored from then on.”

His musical exploration has fueled his Twitch channel’s growth: Thanks to his Mafiathons — monthlong 24-hour streaming marathons that he’s held with some of the most famous names in music, sports and entertainment — Cenat now has the most subscribers on Twitch (728,535 at press time) and holds its record for the most concurrent streamers at 720,000. He’s now also one of the richest streamers in the world, according to Forbes, which estimates his 2024 earnings at around $8.5 million. (Cenat declined to comment on his earnings.)

Andrew Hetherington

His manager, John Nelson, credits these streaming marathons with cementing the Kai Cenat brand. “His first 24-hour stream [in January 2023] is really when his trajectory went off,” Nelson says. “And it’s interesting — I believe it was that one that ended with Ice Spice [on camera]. Funny, because both of them took off at that same time. Two New York kids. And, you know, they were both very popular then, but they weren’t the megastars that they are today.” Each of Cenat’s Mafiathons has helped him not only grow his audience but also break Twitch records; the most recent, in November, featured a who’s who of pop culture that included Serena Williams, GloRilla, Sexyy Red and Druski that helped him break the record for most subscribers, with more than 340,000 new people paying $5.99 to join Club Cenat.

Yes, more than 720,000 people pay money to watch a 23-year-old talk about whatever comes to mind and prank his best friends. But why, exactly?

“I just think it’s the creativity,” Cenat says. “This is just the vibe I give off, like on my stream. I try to make it as fun as possible. And being able to, like, break ice with anybody who comes on.”

It’s the creativity, sure. But it’s the combination of that creativity with his comparatively radical sincerity that has endeared him to Fortune 500 companies like McDonald’s, T-Mobile and Nike. It’s also what drew the likes of Snoop Dogg, the veritable hip-hop pitchman who’s able to move between disparate worlds, to tap the young star to work together. And it’s the reason Hart, the blockbuster comedian who has mastered the art of multimodal content more than perhaps any other superstar, took a liking to him over any other streamer of the moment.

Cenat, much like Snoop and Hart, has built a brand on being genuinely unproblematic, which, combined with his affable demeanor, has appealed to an unusually large swath of people. Unlike several other popular streamers, he hasn’t delved into the incel echo chamber side of streaming culture that has, in part, been popularized by Twitch competitor Kick. The Australian-based streaming platform reportedly offered Cenat $60 million to switch to Kick, but he turned it down.

When asked why, Cenat struggles to articulate a clear metaphor. “Say, for example, you go to Steph [Curry] and you’re like, ‘Hey, man, we want you to be a running back [in] the NFL. You’re so good at basketball, but we want you to just leave everything behind right now and go to NFL football and be a running back,’ ” he says. “It doesn’t make sense! I’ve been on Twitch. I’ve built a core community. Kick is not my home. My home is definitely Twitch. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. That’s what I live by.”

Andrew Hetherington

Andrew Hetherington

And, unlike a number of popular streamers, he’s managed to stay clear of the political discourse that dominated the conversation in 2024. “It’s just because I don’t understand it. Some people say I should just do some research on it and, like, inform myself,” Cenat explains. “Now, I’m living in America, so it’s good to know what’s going on in politics. But like, I’m just not educated enough to speak on that.”

On the early January day I sit down with Cenat, Adin Ross, the superstar Kick streamer who famously interviewed President Donald Trump and gifted him a Tesla Cybertruck, made a statement apologizing for “raising a toxic community” on the platform and vowed to do better. “I want to rebuild,” Ross said. “I want to actually completely revamp and reset everything. I want to go back to stuff that matters. With that being said, every stream that I do, especially at this point, until I say something else, is going to be something that’s heartwarming and something that’s meaningful.”

Sounds a lot like Cenat, doesn’t it? He brushes off the idea. Cenat believes a fan base is a reflection of the creator. “So if you feed it nonsense, you’ll get nonsense. [Ross] realized what happened and now he’s trying to make a big change.”

But regardless of how he frames it, Cenat still has major clout. On Aug. 4, 2023, a full-on riot ensued in New York’s Union Square when he announced to his massive audience that, to celebrate his first streaming marathon, he would be giving away PlayStation 5 consoles and gift cards there. But he didn’t have a permit. Around 3 p.m., large crowds started to form in Union Square, and police took notice when people began to destroy public and private property. The New York Police Department called in 1,000 officers to the scene — and then all hell broke loose. Cars were destroyed, store windows were broken, and seven people were injured, including three NYPD officers. Over 60 people were arrested, half of them minors. It was a rare dark day for Cenat — but it proved just how big his brand and celebrity had gotten.

In 2023, Cenat and his small team — his assistant/production partner Brianna Lewis, his videographers and manager Nelson — traveled to Nigeria. And when they stopped by Makoko, a small, impoverished waterfront settlement on the outskirts of Lagos, they realized they were out of their depth.

The village didn’t have broadly available internet like the city itself, so Cenat couldn’t stream. But what really caught him off guard was the state of the Makoko Children Development Foundation School and Orphanage. “I went over [to Nigeria] just to go visit it, see how it is, and I went out where I just seen things that I was like, damn,” he says. He decided then and there to at least try to help improve the town. “I stumbled across this school that they had in this very small school building. These small classes and the kids were so eager to learn even in the condition that they were in. Don’t get me wrong: When I went to Nigeria, I seen beautiful parts. They got great big houses, fire cars — like, Nigeria is beautiful. [But] the place where I went to was Makoko.”

His first plan was to just fund some renovations to the school, but soon that didn’t feel like enough. So he decided to give 20% of his earnings from his November Mafiathon 2 to build a brand-new school in Makoko. “Hopefully it comes out exactly like what I’m imagining,” he says. “They said it’s going to be done this year probably, and I want to go back to Nigeria and see how it is and [have] like a grand opening. I want to be able to stream that.”

Andrew Hetherington

Cenat’s work in Makoko offers a window into how he envisions his future. He has dreams of doing more with the streaming format, but also, maybe, leaving it all together. Though he loves streaming, he wants to act in and direct movies. (Not TV, though: In his words, “No one watches TV anymore.”) Hart, whom he now calls a friend, has been helping him prepare for that next stage of his career; Cenat won’t share specifics, but says Hart has given him certain movies to watch and has been advising him. “I would love to be in movies and stuff; he definitely pushes me,” Cenat says. “He tries to connect me to the right people that direct and write movies and produce them.”

Would he leave streaming behind for Hollywood? Perhaps — but not right now. “Our good friend, [YouTube superstar] Mr. Beast, was like, ‘Why would you use something that you’re so good at to catapult you into another category? Just be completely dominant in the category that you’re in right now and just take over that.’ And I’m like, ‘Damn, he does make a good point.’ ”

His current solution to the conundrum: eschew Hollywood entirely and produce a movie on his own. “I want to be able to, like, put it out to the world,” he says. “I’m going to take a hit financially. But like, I want to be able to put it out to the world and just see if a company will pick it up.”

For the moment, Cenat remains laser focused on streaming. After all, his is one of the only streams that can genuinely help (or hurt) an artist’s career, at least in his mind. When Cenat panned GloRilla’s 2023 single “Cha Cha Cha” with Fivio Foreign, the Memphis MC blocked him on social media. He felt he was just being honest. “If there’s some bad music, I’m going to let you know it’s bad,” he says. However, according to Cenat, after their dustup, Glo glowed up. “We’re good friends now. And ever since I told her that one song was bad, she’s been making hits!” He’s not wrong. Ever since that spat, Glo has notched five songs in the top 40 on the Billboard Hot 100.

And when the biggest names in entertainment are DM’ing and texting you to ask to visit your crib and hop on your stream, what could possibly measure up next? Going bigger — even bigger than the movies. “I want to go to space!” Cenat exclaims. “I want to be the first human in space to float around, [stream] and talk my talk to my chat and then come back down to Earth.”

He’s serious, too. He wants to do everything he wanted to do as a kid, living and dreaming in that homeless shelter. “I want to have the whole Avengers on my stream one day,” he says with the enthusiasm of a middle schooler. “I really believe that’s going to happen one day.”

This story appears in the Jan. 25, 2025, issue of Billboard.