Business

Page: 40

This week’s roundup of Publishing Briefs includes several signings (and a podcast) at Sony Music Publishing, a new member country for the International Confederation of Music Publishers, and a full slate of updates from the National Music Publishers’ Association’s annual meet-up in NYC.

Big Yellow Dog Music, a Nashville-based publisher and artist development company, signed singer-songwriter and producer Landon Sears. Originally from Danville, Ky, Sears began with bluegrass fiddle before shifting to hip-hop, a genre shift that helped launch his successful career in the K-pop industry. He’s earned platinum records and No. 1 hits in Korea, with credits for top acts like NCT 127, Kang Daniel and CIX. Big Yellow Dog CEO Carla Wallace called Sears’ versatility “liberating,” while senior director Nicole Rhodes added that his “energy, hard work and talent speaks for itself.”

Sony Music Publishing inked UK-born, LA-based songwriter and producer Joe Reeves to a global publishing deal. Known for his work with artists like Post Malone, Ed Sheeran, Juice Wrld, H.E.R. and Morgan Wallen, his credits include tracks on Malone’s chart-topping album F-1 Trillion and Wallen’s latest Billboard 200 No. 1 I’m The Problem. Sony’s Clark Adler praised Reeves’ genre-spanning impact and potential for continued success, adding, “Joe is an incredible songwriter who is constantly upping his game.”

Trending on Billboard

Frank Ray inked a global publishing deal with Sony Music Publishing Nashville. Known for merging his Mexican American roots with contemporary country, Ray has gained attention with tracks like “Streetlights,” “Uh-huh (Ajá),” and his breakout single “Country’d Look Good on You,” which led to his Grand Ole Opry debut in 2022. His latest release, “Miami in Tennessee,” continues blending country and Latin influences. “Frank is a one-of-a-kind talent, and his authenticity shines through in every song he writes,” said Kenley Flynn, SMPN’s vp of creative A&R. “We are thrilled to welcome Frank to the SMP family and can’t wait to see all that’s ahead for him.”

At its annual meeting yesterday (June 11), National Music Publishers’ Association president/CEO David Israelite and general counsel Danielle Aguirre emphasized the need for unity across the industry to boost songwriter compensation. Key battlegrounds for improvement include interactive streaming, general licensing and social media. Spotify’s bundling tactics and Amazon’s revenue cuts were sharply criticized, and the NMPA also highlighted licensing gaps among small and mid-sized venues while taking aim at B2B services for rights violations. Despite challenges, the event — held in NYC — celebrated achievements, honoring songwriters like Kacey Musgraves, Rhett Akins, Gracie Abrams and Aaron Dessner with performances and awards. Read Kristin Robinson’s full wrap of the event here.

Philip Morgan inked a global publishing deal with Warner Chappell Music Nashville and The Core Entertainment. A Texas native now based in Nashville, Morgan has written songs for artists like Chase Matthew (“How You Been (Letter to the County Line Girl)”) and earned acclaim with awards including the 2024 American Songwriter Country Song of the Year with Natalie Otto for “5 O’Clock Shadow” and NSAI’s Chapter Challenge for “Gone, Gone, Gone!” Known for collaborating with industry talent and mentoring emerging artists like Austin Michael and Hunt Pipkin, Morgan is lauded by Benji Amaefule of WCMN as an “emerging force” who “brings a valuable versatility to connect and craft timeless stories in the room.”

Soundcrest Music Publishing signed a co-publishing deal with Nashville singer-songwriter Laura Sawosko. The agreement includes her current and future works, notably her 2025 independent release Not What I Do — “Her songs are real—they draw you in,” says Soundcrest vp of A&R and publishing Michael Owunnah. Soundcrest will support Sawosko through creative collaboration, sync opportunities, and strategic development. She also recently joined PLA Media’s artist roster, boosting her industry presence.

Sony Music Publishing Nashville launched Thank A Songwriter, a new podcast celebrating songwriters in country and beyond. Hosted by SMPN CEO Rusty Gaston, the debut episode — out today (June 12) — features part one of an in-depth convo with hitmaking songwriter Ashley Gorley, coinciding with his induction tonight into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. The podcast will spotlight diverse SMP songwriters, exploring their stories and inspirations.

Electric Feel Publishing signed Toronto-based artist, producer and songwriter Steve Francis Richard Mastroianni. Best known for co-writing Morgan Wallen’s hit “Love Somebody,” Mastroianni has also worked with artists like Dua Lipa, Gordo and Digital Farm Animals. Founder and CEO Austin Rosen welcomed the partnership, calling it the “start of an exciting new chapter.”

MPA Iceland joined the International Confederation of Music Publishers (ICMP), becoming its 80th national member. ICMP represents the global music publishing industry, including both major and indies across 76 national associations on nearly every continent (no Antarctic publishing biz just yet). MPA Iceland advocates for the island nation’s music publishing sector. ICMP Director General John Phelan praised Iceland’s global musical influence, citing artists like Björk and Sigur Rós, and welcomed MPA Iceland to its international network.

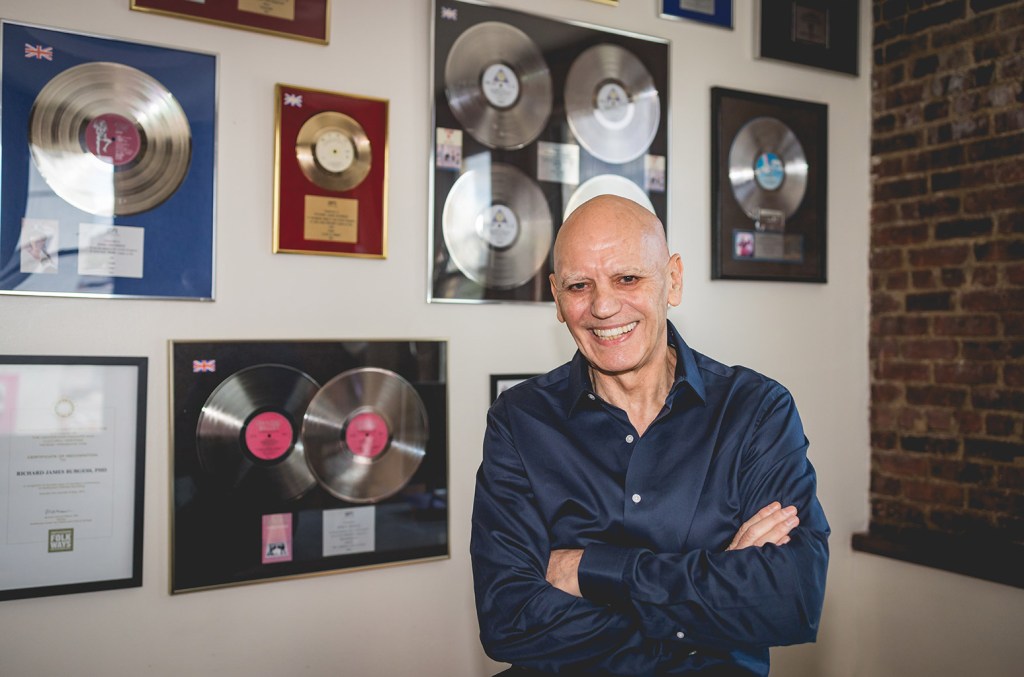

Since January 2016, musicians who have struggled with the vagaries of compensation and regulation in their industry have been able to turn to one of their own for guidance, support and solidarity. That year, Richard James Burgess — who produced four top 20 U.K. hits for Spandau Ballet, managed bands, performed in one and oversaw business operations for Smithsonian Folkways Recordings — became president/ CEO of the American Association of Independent Music.

Next January, Burgess will step down after leading the organization through what Louis Posen, founder of indie label Hopeless Records, describes as “a period of unprecedented growth.” Under Burgess’ purview, Posen says, “A2IM has expanded its membership, created more opportunities for members and launched signature events like Indie Week and the Libera Awards.”

Trending on Billboard

During his 10 years at the helm of A2IM, Burgess also “built a highly engaged coalition of indie labels, large and small, and lobbied hard for them in Washington and across the music industry,” says Mark Jowett, co-founder and president of A&R at Nettwerk Music Group. “He fights each day for fairness and a level playing field,” adds Concord COO Victor Zaraya. “I will miss working with him.”

Burgess says that his stint leading A2IM has been animated primarily by a single principle: “Do what’s best for the creators. It’s the music business. But without the music, there is no business.”

Why did you decide it was time to move on from your role leading A2IM?

I made up my mind when I started that 10 years would be my limit. Mostly my career has fallen into 10-year chunks by accident. I tend to get to a point where I feel like I’m repeating myself. I like to do new things. Also, I think it’s good for the organization to have new leadership.

Over the decade that you’ve run A2IM, how has the definition of “independence” changed?

It still means the same thing it always did. People get confused about what corporate structures do around independence as opposed to what independence means. It means that you own your own copyrights or you have the freedom to do things the way you want to do them. Most artists, if they have the option, decide to go independent rather than with a major because they can steer the direction of their career more. Majors have extremely high goals for sales, and that usually takes a lot of compliance with certain kinds of criteria.

You don’t think that the major labels’ recent acquisitions of indies has changed the definition of independence?

The question is, how much does corporate ownership affect your ability to do the things you want to do? I don’t think it’s a healthy universe where all independents are channeled through the majors. But this is not a new thing. There was a peak of independence in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

There’s a long history of majors buying up indies, but is that happening at a different scale? Universal Music Group [UMG], for example, bought Downtown, which includes FUGA, which provides distribution for many indie labels.

That’s really upsetting a lot of independents. Having said that, there are options. Every time there’s consolidation, there’s a commensurate opening up of opportunities for new businesses and entrepreneurs.

What do you see as the biggest wins during your time running A2IM?

Coming in, I had several goals. One was to expand the organization, to make it more robust and as stable as possible. I think we’ve achieved that. Our revenues are much higher than they were. Indie Week is now a pretty established international conference. The other thing I’m really proud of is that we now are really established in advocacy. Nothing really happens in D.C. without us being involved. We get calls from congresspeople or their offices when there are any issues that might affect the sector, whereas we used to find out about it second- or third-hand or from the press that something was happening that could affect us.

How were you able to bolster the organization’s advocacy operations?

I [previously] worked at the Smithsonian, so I was in the D.C. scene for years, and I had a lot of helpful insight when I came to [A2IM]. The first couple of years, we didn’t have any lobbyists. We had to scrape the money together to afford our current lobbyists. They do an amazing job, and they don’t kill us financially. But frankly, we can spend 10 times as much money on lobbying and we still would not match what our opponents spend.

What are the priorities on the lobbying side?

We’re actually launching our own bills now. We have the HITS Act — that would let independent artists deduct up to $150,000 in music production expenses immediately. Another one is the American Music Fairness Act, which would make sure that artists could get paid from airplay. I’m really happy that songwriters get paid — this is not a zero-sum game. But radio stations are making money from selling ads against those records. Some of those ad dollars should go to the singers.

Another bill we think is really important is the Protect Working Musicians Act, which we launched with the Artists Rights Alliance. It would allow small- and medium-size enterprises — could be an artist, could be a group of labels or publishers or songwriters — to collectively negotiate against much larger [digital service providers] and AI [artificial intelligence] companies. These are among the largest companies that have ever existed. The leverage they have is completely disproportionate. You look at the statements people like Jack Dorsey and Elon Musk are making, which is that [intellectual property] should be considered fair use. When you look at the profits Meta forecast the other day, it’s hard to see why the source material they use to fuel this tool should be free. Nothing else is free. The coding is not free. The storage is not free.

Where are you and the RIAA aligned, and where do you differ?

We’re in constant communication with the RIAA, and we’re aligned on a lot. They’re part of the musicFIRST Coalition [which aims to “end the broken status quo that allows AM/FM to use any song ever recorded without paying its performers a dime”]. There are some differences, but we are 100% aligned on the idea that we need to preserve and increase the value of music copyrights.

In 2023, UMG CEO Lucian Grainge said that while conflict in the music industry was once primarily between indies and majors, today’s divide is “those committed to investing in artists and artist development versus those committed to gaming the system through quantity over quality.” Do you agree?

In 1999, the music industry reached its peak. We’re still down from that in terms of adjusted dollars. And that’s not accounting for the additional usage these days — anecdotally, I think there’s a lot more music consumed today than there was in 1999. Simply because of phones and [earbuds], accessibility has vastly increased. The reason we’re in this position is because we don’t control our pricing or distribution anymore. We gave that up in 1999 when we let Napster slip through our fingers. That can’t happen again. Obviously, we’re not in an exactly parallel situation with AI as we were with the transition to digital. But I do think it’s the music industry and musicians versus the tech platforms. Tech platforms want to lower the cost of what they call “content” and I call “music.” The musicians and the labels want to increase the value.

Are you taking any vacation after you officially step down?

I’m not good at vacation. A vacation to me is doing something different.

Spotify has partnered with industry mental health nonprofit Backline to launch a global hub of mental health resources as part of their nascent Heart & Soul initiative.

Officially dubbed ‘Heart & Soul, Mental Health for Creators,’ the new partnership sees Backline and Spotify joining forces to launch their Global Mental Health Resource Hub, which aims to serve as a comprehensive support platform for industry professionals around the world.

While Spotify first launched its Heart & Soul initiative in 2018 as a way of providing support and deepening understanding of emotional well-being amongst its employees, Backline first emerged in 2019 to connect industry professionals and their family with mental health and wellness resources.

Trending on Billboard

The new partnership sees Backline now expanding their services beyond U.S. borders for the first time, serving as a response to the growing mental health crisis that affects industry workers – be it artists, touring crew and industry professionals – of all levels and locations.

“Backline is honored to serve as a steward of Spotify’s investment into the creative community,” Hilary Gleason, Backline’s Executive Director & Co-Founder, said in a statement. “Bringing our work to scale is a meaningful way to uplift the well-being of artists all around the world.

“This collaboration is taking these invaluable mental health and wellness resources beyond borders. Music knows no bounds, and now people who make music happen have access to care and a compassionate community. Our work together will help ensure that artists have the resources, support, and stability they need to thrive both personally and professionally.”

The new initiative will see Backline’s expanding their resources worldwide, including an international, multilingual database of trusted music industry and mental health support resources and crisis lines from around the world; an email concierge service that provides one-on-one support to aid individuals in navigating care options and mental health systems in their countries; and access to their free digital guide Mind the Music: A Mental Health Guide for the Music Industry.

Additionally, support for songwriters, and access to wellness events are included, as is free therapy access for ambassadors of Spotify’s EQUAL, GLOW, and RADAR programs.

“It’s clear that the mental health challenges artists face are real, and that the current support systems often fall short. It’s on all of us in the industry to respond with action,” noted Monica Herrera Damashek, Spotify’s Head of Artist & Label Partnerships.

“We know this is only one step but we look forward to building on this for a more supported, sustainable environment for the artists who shape culture every day.”

Additionally, Spotify is also providing financial support to expand organizations such as MusiCares, Music Health Alliance, Music Minds Matter, and Noah Kahan’s The Busyhead Project; spotlighting mental health stories from the creative community across Spotify for Artists and Spotify Songwriting; and offering curated playlists, podcasts, and audiobooks to support creators’ wellbeing via the Heart & Soul, Mental Health for Creators hub.

“Heart & Soul is our commitment to the creators behind the music. Artists and songwriters face immense pressure, and their mental health can’t be an afterthought,” added Spotify’s Head of Social Impact Lauren Siegal Wurgaft.

“Supporting creators’ well-being is essential to sustaining a vibrant music ecosystem. By working closely with trusted partners like Backline, we’re not just offering resources, we’re helping drive lasting change in how the industry approaches mental health.”

The Animal Talk kingdom just expanded. The label, founded by dance duo Sofi Tukker in 2018, now encompasses a management company that’s entered a partnership with Palm Tree Management. Sofi Tukker is the first act signed under the agreement.

Along with being a label and management company, Animal Talk is now also an artist collective focused on hosting future Animal Talk events and festivals, creating branded clothing capsules, developing Animal Talk as a lifestyle brand, securing strategic partnerships and more. Animal Talk is being run by Bella Tamis, Palm Tree’s Myles Shear and Mike Hoerner and Sofi Tukker’s Sophie Hawley-Weld and Tucker Halpern.

Animal Talk and Palm Tree Management will work together on management for Sofi Tukker while expanding the brand by signing artists, throwing events and more, effectively creating a management deal that allows Sofi Tukker to grow its vision for Animal Talk.

Trending on Billboard

“We’re so excited to announce our new management company, launching together with Myles Shear, Mike Hoerner and Bella Tamis,” Sofi Tukker tells Billboard in a statement. “We originally started Animal Talk as a label and a party many years ago. We launched LP Giobbi’s career, and threw some insane parties, but we put it on the back burner until now, because we didn’t have the bandwidth to do everything we wanted with it.”

Sofi Tukker continues that the idea for Animal Talk originally came from the Mary Oliver poem “Wild Geese,” which also inspired its debut EP, Soft Animals. “It has been a mantra for us since the very beginning,” the duo’s statement adds. “‘You do not have to be good… You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.’ We’ve been inspired watching what Myles has built with Palm Tree over the years. His entrepreneurial energy is infectious and we are so excited to start building out the Animal Talk world with him and Bella. We’ve learned so much over the past ten years of being artists with amazing people by our side, and feel really grateful to get to pay it forward. We’re excited to build a roster of hardworking, boundary pushing artists who want to build something special with us and make people dance all over the world.”

Shear, the co-founder of Palm Tree Management and Kygo‘s longtime manager, adds that he’s “really excited to be working with such talented artists like Sofi Tukker; they’re once in a generation talent. This partnership is unique and we have built a special team around this.”

“We couldn’t be more excited about working with Sofi Tukker,” adds Hoerner. “They’re incredibly talented artists and even better people who share an entrepreneurial mindset.”

Before partnering with Palm Tree Management and Animal Talk on the company, Tamis spent five-plus years with The Shalizi Group and its client Marshmello. She tells Billboard that “Sofi Tukker has been a driving force in dance music for some time, and it’s been incredible building out Animal Talk alongside them. They have a strong vision for working with like-minded artists’ brands, and we’re excited to keep growing it out.”

“We are excited to sign artists who push boundaries and create lanes that didn’t exist before them,” Sofi Tukker adds. “The goal for the company is to be a place for artists to thrive with a focus on strategy and staying authentic. It will be more than a management company, we have plans for fashion collaborations, parties and festivals in the future. “

U.S. music publishing revenue rose 17% to $7.04 billion in 2024, the National Music Publishers’ Association (NMPA) revealed at its annual meeting on Wednesday (June 11). Last year, the trade organization reported total revenue at $6.2 billion, which was up 10.71% from the previous year.

The event, held at Alice Tulley Hall at New York’s Lincoln Center, is considered a state-of-the-union for U.S. music publishers, and this year, its CEO/president, David Israelite, and general counsel, Danielle Aguirre, focused their presentation on both celebrating hitmakers — like award recipients Kacey Musgraves, Rhett Akins, Gracie Abrams and Aaron Dessner — and on talking about ways to grow revenue even more.

There was also a strong focus on calling on the industry, from executives to songwriters and artists, to stand together. As Israelite said, “We should all stand behind [songwriters]…There has never been a greater need to stand up for the value of songwriters.”

Trending on Billboard

Aguirre and Israelite pointed to three key battlegrounds where remuneration can improve if the industry sticks together: general licensing (licensing for bars, restaurants, venues, etc.); social media; and interactive streaming. As Aguirre noted, 72% of publishing income is under “burdensome regulations” in the U.S. — whether by consent decree or compulsory license — but there are still ways to improve that within the current system.

Interactive Streaming

For interactive streaming, Aguirre reminded the crowd that Phonorecords V proceedings at the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB), which will determine the rate that songwriters and publishers will be paid for U.S. mechanical royalties from 2028-2032, are “fast approaching” in the next six months.

“One of the biggest challenges [for interactive streaming income] continues to come from Spotify’s mischaracterization of its music service into bundles, which forced the conversion of over 44 million subscribers into bundled platforms that those subscribers did not request,” Aguirre said. (Earlier this year, the Mechanical Licensing Collective’s lawsuit against Spotify, which claimed the company’s bundling of premium tiers and resultant cutting of payments to songwriters and publishers was unlawful, was dismissed by a judge who said the rules were “unambiguous.” However, the NMPA continues to attack the platform through various means, including sending mass takedown notices for podcasts and videos on Spotify that do not properly license music.)

Aguirre revealed that in the first year of Spotify’s new bundling change alone, publishers and writers have lost over “$230 million…and these losses will continue if we can’t reverse or correct Spotify actions,” she said. “In fact, if we don’t stop them, we are projected to lose over $3.1 billion through the next CRB period [which ends in 2032].”

Perhaps taking a cue from Spotify, Amazon has also bundled its music service with other offerings, allowing it to cut royalty rates for songwriters and publishers in the U.S. — another change Aguirre hit on in her remarks. “In just the last three months, we’ve seen a 40% decrease in music revenue from Amazon, which has hit the PROs particularly hard,” she said. Notably, the NMPA had a much more hopeful outlook on the Amazon bundle when it was announced; at the time, the organization released a statement saying it was “optimistic” about Amazon’s new offering and had “engaged” with the company in a “respectful and productive way” to find a compensation model for publishers that “will not decrease revenue for songwriters.”

Social Media

Social media is one of the rare areas of publishing where publishers and songwriters can negotiate without any government interference — and the NMPA is hopeful about capitalizing on that. To date, the income stream is still small: Aguirre reported that social sites like TikTok, Instagram, X and others only make up 2% of income for publishers in the U.S.

However, Israelite believes songwriters have the power to say no to this level of compensation and force the companies to treat them better.

“It’s important for songwriters to understand they already have the power to strike,” he said, despite the fact that songwriters do not qualify for a traditional union. “They do so when the people they entrust to license their songs, the music publishers and collecting societies, say no. There are key industries, such as social media, user-generated content, artificial intelligence training and lyric rights, where songwriters have the power to say no. But too often, when a music publisher or a PRO stands up to licensees who don’t want to pay fair rates, we run into a unique problem that plagues the songwriting industry: Songwriters don’t stick together. This is a tough conversation.”

Case in point: Just last year, Universal Music Group removed its catalog from TikTok in an effort to fight for its “fair value.” However, as Billboard reported at the time, a number of artists, including Ariana Grande, Beyonce and Olivia Rodrigo, found ways around the ban to continue using the platform for marketing purposes.

General Licensing

The final area of focus the NMPA addressed at the meeting was general licensing, or the performance license required to play music in public spaces like restaurants, bars, venues and clubs. While Aguirre noted that this only made up for 5% of total revenue last year, she said that “there is a substantial opportunity for growth.”

“One concern is the lack of licensing from many of these venues. For the first time, we have insight into just how much money is being lost to unlicensed mid-sized venues,” said Aguirre. In a recent study, she said the NMPA found that 80% of “venues that have 50 or fewer locations but are large enough to require performance licenses…misuse consumer streaming services to provide that music.” Others, she added, are using business-to-business (B2B) music services that “are not obtaining all of the necessary rights for the services that they are offering. Some provide features like offline listening, interactive music experiences and on-demand streaming without securing appropriate mechanical licenses.”

To remedy this issue, the NMPA announced it’s sending six cease and desist letters to B2B music services that are allegedly not properly paying for music. The organization did not specify the names of these B2B vendors.

The NMPA’s attack on B2B music suppliers comes on the heels of the U.S. Copyright Office’s Notice of Inquiry regarding U.S. PROs, wrapping up its first comment period. While bars, restaurants, clubs and other public spaces license music from PROs to use in their venues, some recently complained about the PROs’ alleged “lack of transparency” and the fact that there’s been a so-called “proliferation” of new PROs in the market, complicating (and perhaps increasing the cost of) the licensing process. While most countries have just one, maybe two, PRO options for writers and publishers to join, the U.S. now has six: ASCAP, BMI, SESAC, GMR, AllTrack and PMR.

Overall Breakdown of Publishing Income Streams

As reported by the NMPA, the breakdown of income streams for U.S. publishers and songwriters is as follows:

Streaming services: 45%

Traditional sync: 8%

Radio: 8%

TV/Cable: 6%

Mass sync: 6%

General Licensing/Live: 5%

Social Media: 2%

Label: 2%

Sheet Music: 1%

Lyrics: 1%

Songwriters

It wasn’t all just business talk — this year’s meeting also celebrated songwriters. The honorees included Musgraves, who received the Songwriter Icon Award accompanied by a tribute from her friend, Leon Bridges, who performed the Musgraves-written song “Lonely Millionaire.” Musgraves also took the stage to perform “Architect” from her latest album, Deeper Well.

Akins received the Non-Performing Songwriter award this year, and the ceremony featured a special tribute from his son, country artist Thomas Rhett, who performed “I Lived It” (released by Blake Shelton) and “What’s Your Country Song,” which he wrote with his father.

Lastly, the NMPA showcased the winners of the Billboard Songwriter Awards. Those honors were originally set to be handed out at a separate NMPA/Billboard Grammy week event that was canceled due to the Los Angeles wildfires and rescheduled for the NMPA’s annual meeting. Abrams and Dessner, who received Breakthrough Songwriter of the Year and the Triple Threat Award, respectively, took the stage on Wednesday to perform “I Love You, I’m Sorry,” which they wrote together.

Atlanta rapper Silento, known for his 2015 chart-topper “Watch Me (Whip/Nae Nae),” has been sentenced to 30 years in prison after pleading guilty to shooting his cousin dead in 2021.

Silento (Ricky Lamar Hawk) had been scheduled to stand trial this week over the death of his cousin Frederick Rooks. Instead, the 27-year-old rapper took a plea deal on Wednesday (June 11).

The rapper pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter, aggravated assault, gun possession and concealing a death but said he was mentally ill when the crimes were committed. The manslaughter charge was downgraded from a harsher malice murder count in his indictment, while Georgia prosecutors agreed to drop another felony murder charge.

DeKalb County Superior Court Judge Courtney Johnson sentenced Silento to 30 years in prison following the plea. He’ll get credit for the four years he’s spent in jail since his 2021 arrest.

Prosecutors claim Silento shot his 34-year-old cousin Rooks multiple times in February 2021 and then fled the scene. Silento allegedly admitted to killing Rooks during a post-arrest interview with investigators, and prosecutors say bullet casings recovered from the scene matched a gun found on the rapper when he was apprehended.

A rep for Silento said when he was arrested in 2021 that the rapper had been “suffering immensely from a series of mental health illnesses.” He was diagnosed with severe bipolar disorder in jail, according to court filings.

Silento’s lawyer did not return a request for comment on the guilty plea and sentence on Wednesday.

“Watch Me (Whip/Nae Nae)” spawned a viral dance craze in 2015 and spent 51 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at No. 3. In 2019, Billboard named the track one of the 100 Songs That Defined the Decade.

Silento faced a number of legal troubles after the success of “Watch Me.” In 2017, he was held in the United Arab Emirates over a business dispute with a local concert promoter, after which a court ordered him to pay 300,000 dirhams ($81,500) for failing to play two scheduled shows in Al Ain and Abu Dhabi.

In 2020, Silento was arrested twice in two days in California for domestic violence and for walking into a stranger’s home holding a hatchet. Later the same year, he was arrested again for driving 143 mph on Interstate 85 in Georgia.

The RIAA is throwing its support behind a blockbuster copyright lawsuit filed by Disney and Universal against artificial intelligence firm Midjourney, calling the case “a critical stand for human creativity.”

The lawsuit, filed earlier on Wednesday (June 11), claims Midjourney has stolen “countless” copyrighted works to train its AI image generator — and it marks the first foray of major Hollywood studios into a growing legal battle between AI firms and human artists.

Disney and Universal’s new case, which comes as major music companies litigate their own infringement suits against AI firms, “represents a critical stand for human creativity and responsible innovation,” RIAA chairman/CEO Mitch Glazier wrote in a statement.

Trending on Billboard

“There is a clear path forward through partnerships that both further AI innovation and foster human artistry,” Glazier says. “Unfortunately, some bad actors — like Midjourney — see only a zero-sum, winner-take-all game. These short-sighted AI companies are stealing human-created works to generate machine-created, virtually identical products for their own commercial gain. That is not only a violation of black letter copyright law but also manifestly unfair.”

AI models like Midjourney are “trained” by ingesting millions of earlier works, teaching the machine to spit out new ones. Amid the meteoric rise of the new technology, dozens of lawsuits have been filed in federal court over that process, arguing that AI companies are violating copyrights on a massive scale.

AI firms argue such training is legal “fair use,” transforming all those old “inputs” into entirely new “outputs.” Whether that argument succeeds in court is a potentially trillion-dollar question — and one that has yet to be definitively answered by federal judges.

Disney and Universal’s new lawsuit against Midjourney is the latest such case — and immediately one of the most high-profile. The 110-page lawsuit claims the startup “helped itself” to vast amounts of copyrighted content, allowing its users to create images that “blatantly incorporate and copy Disney’s and Universal’s famous characters.”

“Midjourney is the quintessential copyright free-rider and a bottomless pit of plagiarism,” the companies wrote in their complaint, lodged in Los Angeles federal court on Wednesday morning.

The case echoes arguments made by Universal Music, Warner Music and Sony Music, which filed their own massive lawsuit against the AI music firms Udio and Suno last summer. In that case, the music giants say the tech startups have stolen music on an “unimaginable scale” to build models that are “trampling the rights of copyright owners.”

Music publishers have filed their own case, accusing Anthropic of infringing copyrighted song lyrics with its Claude model. Numerous other artists and creative industries — from newspapers to photographers to visual artists to software coders — have launched similar cases.

Disney and Universal’s complaint makes the same basic argument — that using copyrighted works to train AI is illegal — but does so by citing some of the most iconic movie and TV characters in history. Disney cites Darth Vader from Star Wars, Buzz Lightyear from Toy Story and Homer Simpson from The Simpsons; Universal mentions Shrek, the Minions, Kung Fu Panda and others.

“Piracy is piracy, and whether an infringing image or video is made with AI or another technology does not make it any less infringing,” lawyers for the studios write. “Midjourney’s conduct misappropriates Disney’s and Universal’s intellectual property and threatens to upend the bedrock incentives of U.S. copyright law that drive American leadership in movies, television, and other creative arts.”

In honor of the FIFA World Cup coming to North America next year, Liberty State Park in New Jersey — located across the Hudson River from Manhattan — has been selected as the official site of the FIFA Fan Festival, produced by Live Nation and DPS.

Met Life Stadium will host eight FIFA World Cup 26 games, including the Final Match. As a result, the NYNJ Host Committee chose Liberty State Park due to its stunning views of the Manhattan skyline and proximity to Ellis Island and the iconic Statue of Liberty. The FIFA Fan Festival NYNJ is expected to attract tens of thousands of fans during the 39-day tournament, which is set to take place from June 11 to July 19, 2026. Besides concerts and chances to participate in soccer challenges, fans can watch real-time match broadcasts and interactive fan activations, as well as activations for FIFA’s various corporate sponsors.

“The FIFA Fan Festival NYNJ will be the largest and most visible fan experience of the entire tournament,” said Alex Lasry, CEO of the NYNJ Host Committee, in a statement. “This isn’t just about watching matches, it’s about celebrating the game” and “creating lasting impact for our communities, partners, and millions of fans.”

Trending on Billboard

As part of its role programming FIFA Fan Festival NYNJ, Live Nation will present a number of premier concerts on non-match days, “creating marquee moments that celebrate the intersection of soccer, music, and culture,” according to a press release.

“The FIFA World Cup 2026 is one of the world’s most prestigious events and an unparalleled opportunity to highlight the region’s diversity and deliver unforgettable fan experiences,” added Geoff Gordon, Chairman of Live Nation Northeast Region. “We’re honored to support the NYNJ Host Committee on this historic moment.”

Production company Diversified Production Services will handle most of the logistics of the FIFA Fan Festival, said Darren Pfeffer, president of DPS, who said in a statement, “The FIFA World Cup draws billions of viewers from all over the planet, and the FIFA Fan Festival NYNJ will enable hundreds of thousands of fans to experience it in an immersive way.”

Christie Huus, chief events officer of the FIFA World Cup 2026 NYNJ Host Committee, added, “There’s nothing more powerful than bringing people together, and the FIFA World Cup will ignite our region with energy and excitement. The depth of experience Live Nation and DPS bring will ensure success in transforming NYNJ into one big block party.”

Tickets for the FIFA Fan Festival go on sale soon at FIFA.com/tickets.

Latin music executive Horacio Rodriguez has launched Fundamentals, a new artist and label services company headquartered in Miami. “Launching Fundamentals marks a new chapter in my journey to support and elevate Latin artists by reimagining their path to success — rooted in innovation, cultural impact, creative freedom, and the long-term sustainability of their businesses in […]

Scooter Braun has been subpoenaed in Blake Lively’s sexual harassment and retaliation lawsuit over the movie It End With Us, with the actress seeking to find out what the music mogul knows about co-star Justin Baldoni’s alleged smear campaign against her.

Deadline first reported that Braun’s company, HYBE America, was notified of subpoenas on Tuesday (June 10), and that Lively plans to serve the document requests on Thursday (June 12). Billboard learned via a source familiar with the matter that the Lively camp subpoenaed both HYBE America and its CEO, Braun, personally.

Lively claims in her lawsuit that Baldoni enlisted crisis PR maven Melissa Nathan to seed negative press coverage of the actress in retaliation for her reporting sexual harassment on the set of It Ends With Us. Lively is now seeking any materials about this alleged smear campaign that are in the possession of Braun and HYBE America, which reportedly owns a controlling stake in Nathan’s company, The Agency Group PR.

Trending on Billboard

Billboard reached out to reps for Lively, HYBE America, Braun and Baldoni for comment. Billboard also reached out to Nathan for comment.

Lively’s subpoena on Braun follows Baldoni’s attempt to serve his own document subpoena on Taylor Swift, a close friend of Lively and public opponent of Braun. Swift and Braun’s feud stems from Braun’s 2019 purchase of the pop superstar’s Big Machine masters, which she bought back last month.

Swift’s reps fiercely criticized her subpoena, saying she was not involved in It Ends With Us and that Baldoni was merely trying to “use Taylor Swift’s name to draw public interest by creating tabloid clickbait instead of focusing on the facts of the case.” Baldoni ultimately dropped the Swift subpoena.

The messy It Ends With Us litigation began in December, when Lively sued Baldoni, claiming sexual harassment and retaliation. Baldoni quickly countersued, claiming the actress, her husband Ryan Reynolds and publicist Leslie Sloane had fabricated the claims and that Lively unfairly seized control over the movie he directed.

A federal judge dismissed Baldoni’s countersuit as legally deficient on Monday (June 9), allowing him to amend breach of contract claims but permanently tossing out his defamation allegations. The dispute is on track to go to trial in 2026.

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio