Business

Page: 116

Mom+Pop Music has become the latest coastal label to open an office in Music City, naming Katie Fagan as president of Mom+Pop Music Nashville.

Fagan was previously head of A&R for Prescription Songs in Nashville for the last eight years and had opened Prescription’s first office outside of Los Angeles.

“I will continue M+P’s legacy by signing tastemaker artists and bands, leaning into the local talent pool in the Americana, folk, alt-country and indie spaces,” Fagan tells Billboard. “While expanding our footprint in Nashville is a priority, we know that these genres span worldwide, and I want to be cognizant of talent within these spaces globally as well. We hope to provide a home to both legacy acts and up-and-comers looking for a strategic creative partnership where we can elevate and uphold the integrity of their artistic vision.”

For now, Mom+Pop Nashville will rely on existing staff in New York and Los Angeles “with the goal of hiring locally when the timing aligns appropriately and strategically,” Fagan says.

“Katie has proven herself an important voice and advocate for creatives in the Americana, folk, and Alt-Country spaces,” said Michael Goldstone, founder of Mom+Pop, in a statement. “No one is better suited to reinforce and grow Mom+Pop’s presence in Nashville and globally as we broaden our industry aesthetic.”

Trending on Billboard

At Prescription, Fagan, who has been featured on Billboard’s 40 Under 40 and Women in Music lists, worked with a number of acts, including Joy Oladokun, Anderson East, Maggie Rose, Nick Bailey, Sarah Hudson, Malibu Babie and Cirkut, as well as songwriters/producers who landed placements with Lana Del Rey, Chris Stapleton and Noah Kahan, among others.

Fagan is also co-founder of The Other Nashville Society (TONS), which helps promote non-country music in Music City through its 1,500 members; a member of She Is The Music’s songwriting and publishing committee; and a governor of the Recording Academy’s Nashville chapter.

Mom+Pop, which was formed in 2008, includes Caamp, Chaparelle, Del Water Gap, Magdalena Bay and Pablo Pablo on its current roster. The self-distributed label has a staff of 25 with offices in New York, Los Angeles, London and Nashville.

Billy Joel is in a New York and New Jersey state of mind. During his 2025 tour, which kicks off March 15 in Toronto, Joel will play all three New York City-area sports stadiums, making him the first artist to ever play all three in one summer. His impressive feat will come over a month-long […]

Megan Thee Stallion (Megan Pete) and her legal team have been granted permission to depose Tory Lanez (Daystar Peterson) behind bars following a ruling by a federal judge on Monday (Feb. 24). “Plaintiff may take the oral deposition of Daystar Peterson, either remotely via videoconference technology or as otherwise arranged upon agreement with the California […]

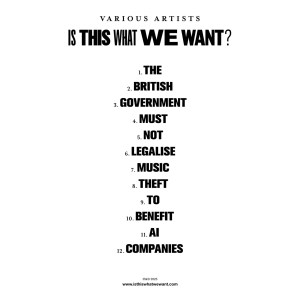

Kate Bush, Damon Albarn, Annie Lennox and Hans Zimmer are among the artists who have contributed to a new “silent” album to protest the U.K. government’s stance on artificial intelligence (AI).

The record, titled Is This What We Want?, is “co-written” by more than 1,000 musicians and features recordings of empty studios and performance spaces. In an accompanying statement, the use of silence is said to represent “the impact on artists’ and music professionals’ livelihoods that is expected if the government does not change course.”

The record was organized by Ed Newton-Rex, the founder of Fairly Trained, a non-profit that certifies generative AI companies that respect creators’ rights. The tracklisting to the 12-track LP reads: “The British government must not legalise music theft to benefit AI companies.”

Is This What We Want? is now available on all major streaming platforms.

Also credited as co-writers are performers and songwriters from across the industry, including Billy Ocean, Ed O’Brien, Dan Smith (Bastille), The Clash, Mystery Jets, Jamiroquai, Imogen Heap, Yusuf / Cat Stevens, Riz Ahmed, Tori Amos, James MacMillan and Max Richter. The full list of musicians involved with the record can be viewed at the LP’s official website. All proceeds from the album will be donated to the charity Help Musicians.

Courtesy Photo

The release comes at the close of the British government’s 10-week consultation on how copyrighted content, including music, can lawfully be used by developers to train generative AI models. Initially, the government proposed a data mining exception to copyright law, meaning that AI developers could use copyrighted songs for AI training in instances where artists have not “opted out” of their work being included.

The government report said the “opt out” approach gives rightsholders a greater ability to control and license the use of their content, but it has proved controversial with creators and copyright holders. In March 2024, the 27-nation European Union passed the Artificial Intelligence Act, which requires transparency and accountability from AI developers about training methods and is viewed as more creator-friendly.

Speaking at the beginning of the consultation, Lisa Nandy, the U.K.’s Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, said in a statement: “This government firmly believes that our musicians, writers, artists and other creatives should have the ability to know and control how their content is used by AI firms and be able to seek licensing deals and fair payment. Achieving this, and ensuring legal certainty, will help our creative and AI sectors grow and innovate together in partnership.”

Industry body UK Music said in its most recent report that the music U.K. scene contributed £7.6 billion ($9.6 billion) to the country’s economy, while exports reached £4.6 billion ($5.8 billion).

“The government’s proposal would hand the life’s work of the country’s musicians to AI companies, for free, letting those companies exploit musicians’ work to outcompete them,” said Newton-Rex in a statement on the album release. “It is a plan that would not only be disastrous for musicians, but that is totally unnecessary: the UK can be leaders in AI without throwing our world-leading creative industries under the bus. This album shows that, however the government tries to justify it, musicians themselves are united in their thorough condemnation of this ill-thought-through plan.”

Jo Twist, CEO of the British Phonographic Institution (BPI), added, “The UK’s gold-standard copyright framework is central to the global success of our creative industries. We understand AI’s potential to drive change including greater productivity or improvements to public services, but it is entirely possible to realise this without destroying our status as a creative superpower.”

Speaking to Billboard U.K. in January, alt-pop star Imogen Heap — a co-writer on Is This What We Want? — expanded on her approach to AI. “The thing which makes me nervous is the provenance; there’s all this amazing video, art and poetry being generated by AI as well as music, but you know, creators need to be credited and they need to tell us where they’re training [the data] from.”

Billy McFarland‘s against-all-odds comeback festival has an official ticketing partner, location and new date, but skeptics still have plenty of reasons to doubt the convicted fraudster’s claims that Fyre Fest 2 won’t be a repeat of his 2017 disaster in the Bahamas.

On Monday (Feb. 24), Austin-based secondary ticketing site soldout.com announced an exclusive ticketing partnership with Fyre Festival 2, which the release announced was to be held on Isla Mujeres in Mexico from May 30 to June 2, 2025 (roughly a month later than the previously-announced dates of April 25-28). Isla Mujeres is a popular tourist destination in the Caribbean Sea about a 30-minute ferry ride from Cancun, located in the state of Quintana Roo.

Tickets for Fyre Fest 2 start at $1,400 a piece for a four-day pass (airfare and hotel not included) and go as high as $25,000 for artist passes that include backstage access and overnight stays at one of two high-end hotels on the island. There’s even a $1 million package for eight people that McFarland says includes access to luxury villas, a private marina with high-end yachts and a private jet to and from Cancun.

Trending on Billboard

Fyre is handling the primary sale of tickets through its own internal system and is utilizing soldout.com for secondary sales. On its website, soldout.com guarantees fans a 100% refund of their money if an event is canceled and not rescheduled. Notably, fans seeking a refund for the 2017 festival received pennies on the dollar due to the festival’s bankruptcy.

Andrew Hentrich, president of Soldout.com, affirms that his company does guarantee refunds if the fest is canceled, noting that “all proceeds from Fyre Festival ticket sales on SoldOut.com are held securely and will not be settled with Fyre until after the event has successfully taken place. Additionally, SoldOut.com is fully insured and financially equipped to issue refunds if necessary, ensuring buyers are protected in the event of cancellation or significant changes to the festival date. This policy applies to all events listed on SoldOut.com, not just Fyre Festival.”

McFarland has been teasing Fyre Festival 2 as a redemption project and personal rebrand since being released from prison and into a halfway house in May 2022. McFarland served four years of his six-year sentence after admitting to defrauding investors in the disastrous 2017 Fyre Festival, which was promised as a luxury destination music event via extravagant promotion from A-list celebrity influencers. But when ticketholders showed up on Great Exuma island in The Bahamas, they found the event they were promised was totally unrealized. McFarland also pleaded guilty to charges in a later ticket-selling scam.

McFarland promises Fyre Festival 2 will be different, and nailing down a location and locking in a date for the festival are major milestones. A press release also announced that Mexican concert production company LostNights would handle festival logistics.

“FYRE Festival 2 is about the adventure into the unknown, curating elite, once-in-a-lifetime experiences,” McFarland said in a statement. “Soldout.com’s background in the music festival world will ensure that our guests have a seamless ticket-buying process from start to finish. Soldout.com is a great addition to the team which also includes Lostnights, our talented and accomplished festival producer and operator.”

The next step will be securing talent for the festival. Billboard reached out to two of the largest booking agencies for music festivals and both said no one has contacted them from Fyre Festival or LostNights to book musical talent.

Gossip blogger Tasha K has agreed in bankruptcy court to pay Cardi B more than $1 million over the next five years and to not make any “derogatory, disparaging, or defamatory statements” about the superstar.

In court filings Friday (Feb. 21), attorneys for Tasha (Latasha Kebe) offered a plan to resolve her years-long federal bankruptcy case — proceedings made necessary by a $3.9 million judgment for defaming Cardi with outlandish claims of drug use, STDs and prostitution.

The new plan will cover only $1.2 million — less than a third of that fine. But under the terms of the agreement, Tasha will still owe the rest of the damages award even after she finishes the repayment plan: “The Almanzar Claim is non-dischargeable.”

Trending on Billboard

In the first year of the agreement, known as a “plan of reorganization,” Tasha will pay $44,907 per quarter to her unsecured creditors, the vast majority of which will go to Cardi. By year five, those quarterly payments will escalate to $81,057.

In an unusual feature, the bankruptcy plan also includes a non-disparagement clause, barring Tasha not only from defaming Cardi while the plan is in place but also from even mentioning her or any of her family members.

“The Debtor shall ensure that no content related to Ms. Almánzar and/or her family, whether explicitly or implicitly, will be published or disseminated on any of the Debtor’s social media accounts, websites, blogs, or other online communication channels,” her lawyers wrote.

Attorneys for both sides did not immediately return requests for comment.

The filing is the latest wrangling in Cardi’s long-running efforts to collect on the huge 2022 judgment, which came after a federal jury found that Tasha had made false and defamatory statements about the superstar on YouTube and other platforms.

Cardi has repeatedly vowed to recover that money by any means necessary — saying “imma come for everything” and “b—- better have my money.” Tasha filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2023, saying she still owed $3.4 million to Cardi and had less than $60,000 in assets. But the rapper has pursued her, later winning a ruling that Tasha couldn’t use the bankruptcy process to “discharge” the judgment.

In December, Cardi’s attorneys demanded that the bankruptcy case be dismissed entirely, accusing Tasha of orchestrating a “long-running fraudulent scheme to shield debtor’s assets and income from creditors.” They said she had fraudulently transferred and concealed money and had lied to both Cardi and the federal courts.

“It is clear and irrefutable that debtor has admittedly and repeatedly engaged in bad faith conduct to hinder, delay, and defraud Ms. Almánzar from collecting on the amended defamation judgement,” the star’s lawyers wrote. “This court should not allow debtor to further abuse the bankruptcy process.”

A day after Cardi filed her motion to dismiss, the court-appointed trustee — a neutral third party who helps shepherd a bankruptcy case toward a repayment plan — filed her own motion endorsing Cardi’s arguments and urging the judge to dismiss Tasha’s bankruptcy case.

The threat of such an outcome likely forced Tasha’s attorneys to negotiate Friday’s agreement, avoiding the risk that the bankruptcy would be dismissed entirely.

Warner Music’s independent music distribution and artist services arm, ADA, has partnered with Three Six Zero Recordings to handle global distribution for all new releases from the label, the companies announced on Monday that (Feb. 24). Three Six Zero Recordings represents multi-platinum acts like WILLOW, Jaden and The Prodigy, as well as artists such as […]

Ed Sheeran wrapped his six-city tour of India on Feb. 15 with more than 120,000 tickets sold, according to Indian entertainment platform BookMyShow. Sheeran played seven nights across the country as part of his + – = ÷ x Tour that is continuing on to China, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain and more. The India […]

For years, record labels have lamented country radio’s pokey approach to single cycles. But at this year’s Country Radio Seminar (CRS), which started Feb. 19 and concluded Feb. 21, even radio programmers are frustrated with the approach.

“It shouldn’t take a year for a good song to get to No. 1,” Cumulus vp of country Travis Daily said during the “Why Can’t We Be Friends” panel on Feb. 19. “We, on my side, are like, ‘People get bored easy, so let’s slow it down.’ It’s dumb.”

Panelists used Cole Swindell’s “Forever to Me” as an example: The track reached the top 10 on the Country Airplay chart dated March 1 after 45 weeks (see On the Charts, page 4). It had all the hallmarks of a hit — an emotionally appealing release from one of country’s most consistent hit-makers — and yet stations had a difficult time committing to it. Meanwhile, digital streaming providers, based on the data from customer reaction, responded commensurately and ran it through their hit cycle. Thus, country radio — once the genre’s primary source of music discovery — seems slow, uncertain and sheepish next to more nimble competition.

Trending on Billboard

“[DSPs] had to come off of it because the audience wants fresh,” Warner Music Nashville senior vp of radio and streaming Kristen Williams said. “They want something new and they want it faster.”

As a result, Williams’ team is using a bifurcated marketing campaign for Swindell, pushing country radio toward the label’s goal of a No. 1 single with “Forever to Me” while talking with DSPs about the singer’s latest track, “Kill a Prayer.”

“This is actually more commonplace than not,” Williams said.

The conversation took place as the country industry again reevaluates its tactics and relationships at the annual seminar, founded as an event for broadcasters and labels that has expanded in recent years to include streaming-related panels. CRS hosts a series of educational panels daily with plenty of showcase opportunities available during label-sponsored lunches and nighttime performances. This year’s event has already featured performances by Brothers Osborne, Jelly Roll, Jordan Davis, Avery Anna, Old Dominion, Dylan Schneider and Brad Paisley, who apologized to programmers who had to wait in single-digit wind chill for entry into the Ryman Auditorium at the Universal Music Group Nashville lunch on Feb. 20.

“The temperature outside,” Paisley said sarcastically, “is what it’s like to play for you.”

The joke received an appreciative groan from the programmers in the audience, who have enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with Paisley since his introduction to radio in 1999. Country artists have typically gone on expensive radio tours for decades, performing for radio staff in conference rooms and forging a rapport that would hopefully lead to personal investment in the artists’ careers. But the relationship has changed with the maturation of the streaming business.

In an earlier time, country artists released three or four singles per year, and those that succeeded would peak on the chart in 12 to 18 weeks. Around the time that Paisley debuted, CRS attendees were encouraged to hang on to their hits longer, which slowed the number of singles and made it more difficult to establish careers.

With the growth of DSPs, artists are once again able to release more music and cycle through the hits quicker, creating stronger relationships with their consumers. Those expensive radio tours have mostly dried up — Cox Media/Houston director of operations Travis Moon estimated that KKBQ has had only four or five artists visit the station on a radio tour in the last year. Programmers seem to be recognizing that playing the same hits for longer periods may be a competitive disadvantage.

“Music is moving faster than ever, [while] the charts are going slower than ever,” said Sticks Media owner Todd Nixon during the Feb. 20 panel “Cycle of a Song” that focused on Tucker Wetmore’s “Wind Up Missin’ You.” “We just got to go faster on this record.”

Programmers have long believed that listeners prefer familiar music over new songs, though a Nuvoodoo study, “The Country Fan — Reviewing, Retaining, and Recruiting Your Listeners,” presented Feb. 20, suggested that overfamiliarity may be hurting radio more than new music. Commercial breaks are the top reason for tune-out, with 47% of the study’s respondents citing them as a factor. Three different kinds of repetition — playing songs too frequently, burnout and tracks appearing at the same time on successive days — were each cited as a problem by more than 40% of respondents. But only 34% of listeners said they turned off the station because they “don’t know” a song.

Therefore, feeding a healthy amount of new music, slotted in the right position on the playlist, may be one of the ways to counter the repetition issues.

“If you just take conventional wisdom constantly, you create narratives and biases in your own head and you’ll bore the audience to death,” Bonneville/Denver director of operations Brian Michel said during “Sound Off: What Is ‘Mainstream’ Country?” on Feb. 20.

Stations with minimal research of their own might consider watching Spotify’s Hot Country playlist, which features material that’s previously proved itself in other forums.

“You can trust that if something is in Hot Country, it is performing well with the mainstream country audience,” Spotify Nashville head of editorial Rachel Whitney said during the “Sound Off” panel. “Then use your own judgment about whether or not it matters to your audience.”

Even if country radio is considering a course correction, the medium remains a venerable institution, and the artists — all of whom grew up with it playing a significant role in their exposure to the music — continue to show their appreciation.

“You guys have changed my life in the last year,” Wetmore said during the “Cycle of a Song” panel. “Truly, from the bottom of my heart, thank you.”

That’s one aspect of CRS that remains the same.

Big Machine Records has signed to its roster duo Something Out West, featuring actor/musician Chet Hanks and musician Drew Arthur. The duo’s debut song for the label, “Leaving Hollywood,” is set to release Feb. 28, while Something Out West is currently working on a project with producer Julian Raymond. Big Machine Records’ roster also includes Tim McGraw, Carly Pearce, Midland, Rascal Flatts, Jackson Dean and more.

The duo formed after Hanks and Arthur were roommates in California while each was setting out on a journey toward sobriety. The friendship evolved into musical collaboration and songwriting sessions. In 2018, Hanks and Arthur recorded under the name FTRZ, releasing the song “Models.” Eventually, they made their way to Nashville to continue writing and recording.

Trending on Billboard

Hanks previously told US Weekly the upcoming new music is based off of “a lot of meaningful life experiences and heartbreak and all that good stuff.”

“Drew and Chet are building a one of a kind sound and story with Something Out West, powered by their undeniable energy and creative connection,” Big Machine Label Group chairman & CEO Scott Borchetta said in a statement. “We’re thrilled for them to join the Big Machine Records family and for the world to experience this fresh, dynamic duo.”

“Upon the first moment meeting Chet and Drew, I was immediately struck with their creative spirit and artistic vision,” added Kris Lamb, evp/general manager of Big Machine Records. “Something Out West know exactly who they are, and Big Machine Records is thrilled to fuel their journey.”

“We’re thrilled to partner with Big Machine and Scott Borchetta,” Hanks said in a statement. “The support they’ve shown for ‘Leaving Hollywood’ and the rest of the music has been incredible. Drew and I have been making music together for a long time, and we feel really proud to have a home at Big Machine for this upcoming project.”

“I wrote ‘Leaving Hollywood’ five years ago, but it feels like the timing and the way we’re releasing it were always meant to be,” Arthur added. “We’re excited for people to hear what we’ve been working on.”

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio