AI

Page: 3

Trending on Billboard

On Wednesday (Oct. 29), Universal Music Group came to a landmark agreement with AI music company Udio. The deal ends UMG’s involvement in the lawsuit against Udio, which it filed last summer with the two other major music companies — Sony Music and Warner Music Group. In the lawsuit, the labels accused Udio of infringing on its copyrighted sound recordings to train its AI music model, which can generate realistic songs in seconds.

Wednesday’s deal went beyond a “compensatory” legal settlement for UMG and Udio, as stated in the press release; it also provides licensing agreements for UMG’s recorded music and publishing assets, creating a new revenue stream for the company and its signees. Participating UMG artists and songwriters will be rewarded for both the training process of the AI model and for its outputs, according to a source close to the deal.

Related

The deal also means that Udio will significantly revamp its existing business. In 2026, Udio and UMG plan to work together to launch a new collaborative platform that will combine music creation with streaming capabilities. According to the press release, the new platform will be “powered by new cutting-edge generative AI technology that will be trained on authorized and licensed music. The new subscription service will transform the user engagement experience, creating a licensed and protected environment to customize, stream and share music responsibly, on the Udio platform.”

The source close to the deal says that Udio users will not be able to export works made within Udio’s forthcoming platform. Instead, they can enjoy their creations within the service, which will be geared towards superfans.

To talk about the new deal, along with Udio’s plans for 2026, Billboard got on the phone with Udio CEO Andrew Sanchez minutes after the deal was announced. You can read the Q&A below.

What was the turning point in negotiations with UMG when you felt like both companies could actually become partners?

Sanchez: We share a really similar vision about what we want to do. The thing that I think is going to be the most extraordinary thing for the music industry in general is when people can do things with their favorite artists and their favorite music. Actually, I think that we had agreements with UMG across the board on this. We said, “Look, we want the human to be centered in this. We want the AI to empower human creators. And we also think, by the way, that that’s actually going to really expand the market.” There actually was a lot of — we had a philosophical alignment on that throughout the whole process. And then the question was, it’s incredibly complex. It’s not something [where] we can pull something off the shelf. We had to actually walk through and figure out how it would all work, and that’s just based on time.

How long did your negotiations with UMG last?

Many months.

One of the things that I thought was really interesting in the press release about this deal is that it notes that Udio will be a “creation, consumption and streaming” destination. Right now, I think of Udio as a place for creation. Can you provide more insight about your vision for this forthcoming 2026 platform with UMG that will do it all?

You’re a keen reader. We believe there’s an incredibly exciting market that combines creation and consumption, both of human-generated songs and of AI-generated songs. We are building a platform that is going to allow you to engage in both of those activities, because that’s where we think the market and users want to go. By the way, we also think that’s the way that artists are going to benefit from this enormously. Because if you can go and you can do stuff with your favorite artists, make a song in their style or remix [a] favorite song, you’re also going to listen to their own music. And we want to be able to meet the users and provide them one place to do that.

It sounds like some of the capabilities you’ll provide with this new platform include mash-ups, remixes and speed controls of existing music. There’s already a few things on the market that do these sorts of things — MashApp, Hook and even Spotify sounds like it’s working on tools like that. How will you make Udio stand out from the pack?

There’s a couple of ways. It’s not just remixing and mashing up. It’s also creating in the style of artists with their opt-in. There’s a huge amount of desire for this, and we know that when we do this the right way with the artist, a huge amount of value will be made for the fan and revenue for the artist.

If I were to say I want to make a pop ballad in the style of Taylor Swift, I can now do that because it’s all licensed?

Well, I don’t want to get specific with artists. It’s their choice, but yeah, in the new service, you would be able to do that, and you’d be able to make extraordinary music. I mean, our model is already really powerful. You can imagine what it’s like when you get to do it directly with the artist’s input and their voice and style, and then the artist gets to benefit from that in multiple ways. They get the financial upside from it. They can increase their brand. And the user gets to go deeper in their connection with you as a fan.

Can users export what they make in Udio to streaming services now?

Not now. That’s an important component of this deal. As we’re entering this transition period, when we’re building out our new models and functionality, you’re not able to have songs leave the platform.

Sony and Warner still have active lawsuits against Udio. Are you confident that they will come to the table now that you’ve reached a deal with UMG?

This is something I need to pass on answering.

There are three parts to this. You have your “compensatory” deal with UMG that settles the lawsuit. Then you also have licenses with UMG on the publishing and recorded music side for this future Udio platform. Does this first part mean you are now retroactively paying UMG for the licensing of their recordings for training data?

To be honest, I think I’d be a little bit over my skis on this, and there’s a lot of legal complexity around that. I don’t think I’m in a position to actually speak about that directly.

Now that you have publishing and recorded music licenses in place with UMG, how does the process of compensating participating artists work? Are you doing a system of attribution or digital proxies for payment?

I wish I could give more details about this right now, but it’s something that we have a clear plan for. This is a trade secret for the moment.

Given this past history with this lawsuit, I imagine that a number of artists will be hesitant about opting in and working with your team. How do you plan to reassure UMG artists who might be hesitant but are interested in diving into AI?

So I think the way to do this is to say you have control, right? We’re very clear about this: If you want to participate, that’s great. If you’re unsure about participating, call me, I’ll sit down with you, and we will talk about it. Call Universal. They’ve been working and thinking about this alongside us. We’ve built and invested an absolutely enormous amount into controls. Controls over how artists’ songs can be used, how their styles can be used, really granular controls. And I think that the way for artists to become comfortable with this is to just talk to me or anyone on the team, and we can walk them through what’s possible.

One of the things that you’ll see is we’re going to launch with a set of features that has a spectrum of freedom that the artist can control. There are some features that will be available to users that will be more restrictive in what they can do with their artists or their songs. And then there will be others that are more permissive. The whole point of it is not only education but just meeting artists at the levels they’re comfortable with.

I think this is something that, when done right, can bring an enormous amount of interest and fan engagement. By the way, data is a huge thing for artists. So imagine that you’re an artist, you’re a hip-hop artist, people are on the platform, and 60% or 70% of them are remixing your songs or using your style in a country song. That’s amazing information that we will provide artists in the back end. They’re going to have this new insight into what people like and want. And I also hope that will inform their own music making.

Interesting. So it sounds like artists aren’t just doing a blanket opt-in here. It’s more granular, and artists can pick and choose what they want to say yes to?

One hundred percent. I also think what we’ll see is, artists at different points in their career are going to also have different views on this — when they’re trying to break, and they want to get their name out there, you know, versus when they’re at the peak of their career. We are ready to learn about that, and we’ll meet them where they’re at.

Since this is a destination for creation and streaming, it feels like an interactive product. Do you have any plans to integrate social features into this, too?

Yeah, for sure. I think that we want to build a community of superfans around creation. As we say internally, it’s connection through creation — whether that’s with artists or that connection with other music fans. We want to lean into that. I think it’s going to be a huge asset for artists and fandoms.

So this platform will now include artists’ voice models, correct?

It’s going to involve all kinds of AI models, like a base model, and then we will have a specific…it’s hard to describe. The best way to explain it, [is it] will have sort of like flavors of the model that will be specific to particular styles or artists or genres. And this, again, provides an enormous amount of control.

Who is your ideal user base for this, since it’s a departure from what you’re doing right now?

I think our ideal user is a passionate music fan who maybe hasn’t created yet, but has the impulse to do so. And if they’re given tools, or they’re given experiences that are straightforward, and they’re given a community that they can engage with, they’re going to want to go deeper. I think that people are going to create songs, or there’ll be songs for you made by people in the communities that you love. I think it’ll be an interesting combination of creation and consumption. I think it goes towards people who are just deep music lovers, who want to go further than is possible today, further than is possible on any of the normal forms of music consumption that we have right now.

Now that Udio is moving forward with this partnership with UMG, I’m wondering, how do you feel this deal can help differentiate the direction that Udio is going in versus Suno, since so many people have lumped the two companies together for so long?

I think that we’re clearly building into a totally new space. I mean, what I’ve described to you isn’t even a question of Udio versus other players. Today, we are breaking new ground on a market that combines new forms of AI and artist interaction — creation and consumption. We’re making a new market here, which we think is an enormous one. I think that we’re already incredibly differentiated just today, just by saying all of this.

Anything else to add?

Partnership is absolutely vital to doing this. This has to be done with artists and songwriters and rights holders, and we are super thrilled about this announcement today, and we want to do this with other artists across the board. So we’re ready to build alongside the entire user community.

Trending on Billboard

Universal Music Group (UMG) and Udio, one of the top AI music models on the market, have announced a strategic agreement, thereby settling UMG’s copyright infringement litigation against Udio. Now, a press release from UMG states that the two companies will also “collaborate on an innovative, new commercial music creation, consumption and streaming experience.”

This deal includes a compensatory legal settlement for UMG, which sued Udio and its rival Suno with the two other major music companies in June 2024, accusing the two platforms of copyright infringement on an “almost unimaginable scale.” At the time, Suno and Udio were using UMG and the other majors’ copyrighted sound recordings to train their models, which could make realistic songs at the click of a button, without a license in place. (Sony Music and Warner Music Group are still involved in the lawsuit against Udio and Suno).

Related

According to the press release, this deal goes beyond just settling the lawsuit — it also provides licensing agreements for recorded music and publishing to UMG, creating a new revenue stream for the company and its signees. Notably, the lawsuit was only focused on the apparent infringement of UMG’s sound recordings, so this now provides a licensing framework for not just sound records but songs as well. Participating UMG artists and writers will be rewarded for both the training process of the AI model and for its outputs, according to a source close to the deal.

For now, Udio’s existing model will remain available for users as the AI company transitions over to this new model with UMG. Any song created with Udio’s existing model will be “controlled within a walled garden,” according to the release, and there are already amendments to Udio in place to make sure that all songs created with it are fingerprinted, filtered and more. According to a source close to the deal, users are not able to export their Udio songs for now.

The new collaborative platform will be launched in 2026, and UMG artists and songwriters can participate in it on an opt-in basis. The press release states it will be “powered by new cutting-edge generative AI technology that will be trained on authorized and licensed music. The new subscription service will transform the user engagement experience, creating a licensed and protected environment to customize, stream and share music responsibly, on the Udio platform.” The source close to the deal adds that works made within Udio’s forthcoming platform cannot be exported. Instead, users can enjoy their creations within the service, which will be geared towards fans. Some capabilities are said to include mashups, remixes and tempo changes to existing, licensed works as well as voice swapping with UMG artists’ voices who have chosen to make their vocals that available to users.

Related

This marks UMG’s latest collaboration with an AI music company, and certainly its biggest announcement to date. In the past few years, UMG has struck deals with “responsible” AI music companies, as the company often calls them, including KLAY, SoundLabs and Pro-Rada. More deals between UMG and AI companies are expected to arrive in the coming days.

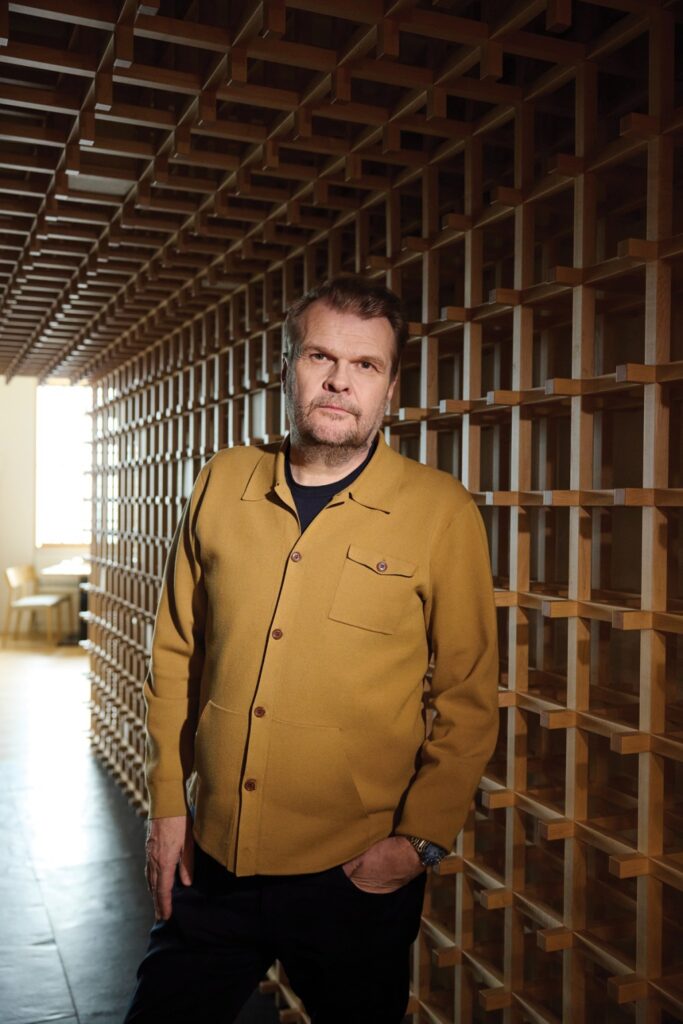

“We couldn’t be more thrilled about this collaboration and the opportunity to work alongside UMG to redefine how AI empowers artists and fans,” said Andrew Sanchez, co-founder & CEO of Udio, in a statement. “This moment brings to life everything we’ve been building toward — uniting AI and the music industry in a way that truly champions artists. Together, we’re building the technological and business landscape that will fundamentally expand what’s possible in music creation and engagement.”

Lucian Grainge, chairman and CEO of UMG, said, “These new agreements with Udio demonstrate our commitment to do what’s right by our artists and songwriters, whether that means embracing new technologies, developing new business models, diversifying revenue streams or beyond. We look forward to working with Andrew who shares our belief that together, we can foster a healthy commercial AI ecosystem in which artists, songwriters, music companies and technology companies can all flourish and create incredible experiences for fans.”

Trending on Billboard ASCAP, BMI and SOCAN have all adopted policies to accept registrations of musical compositions partially generated using artificial intelligence (AI) tools, the PROs jointly announced Tuesday (Oct. 28), while noting that they will continue to reject registrations of fully AI-generated works. According to a press release, all three PROs define a partially […]

Trending on Billboard

The Velvet Sundown is an AI-generated rock four-piece that captured worldwide attention in June after word of the surreptitiously computer-made music spread online. The music is a mix of classic rock, folk and psychedelic Americana. The album’s surrealist artwork evokes Salvador Dali during a stint in the high desert of the American Southwest. The band came replete with an AI-generated press photo and a halfway believable bio.

News of The Velvet Sundown’s AI origins spread like wildfire, and U.S. on-demand streams quickly jumped to approximately 140,000 per week, according to Luminate. The dramatic rise revealed strong curiosity about a band with a fully formed concept but no human creativity. Interest reached a fever pitch the following week when weekly on-demand streams jumped to 760,000. That turned out to be the band’s high-water mark.

Related

Streaming activity dropped 25% the following week, and another 7% the week after. Then interest in The Velvet Sundown fell off a cliff. Weekly streams plunged 48%, then 34%, and then another 25%. Six weeks after hitting its streaming pinnacle, The Velvet Sundown’s weekly on-demand streams were just 15% of its peak number. In another nine weeks, those streams were just 7% of the peak week.

The band’s Google search traffic followed a remarkably similar trajectory. The number of searches for “The Velvet Sundown” peaked the same week that on-demand streams did, and then steadily dropped.

When plotted on a chart, The Velvet Sundown’s weekly U.S. on-demand streams and U.S. Google search traffic look like one-half of a seismometer after a massive earthquake. A sharp peak of curiosity — measured in streams and searches — was followed by a cliff of disinterest.

The shape of the curve says a great deal about both The Velvet Sundown and AI music in general. If AI music is fortunate enough to find an audience, it won’t be easy to keep listeners engaged. Maintaining and building an audience is the domain of record labels, artist managers and armies of service providers and consultants. People see chart positions, news appearances and social media mentions, but they don’t see the behind-the-scenes blocking and tackling that creates all that visibility. The Velvet Sundown had the benefit of being one of the first AI artists most people encountered. Once that novelty wore off, it was left to compete with far more organized, more resourceful artists.

Related

Enter Xania Monet, an AI-based R&B artist who signed a multi-million-dollar deal with Hallwood Media in September. Monet is the creation of Mississippi artist Telisha Jones, who used AI music platform Suno to create songs based on lyrics she penned herself. Monet could have had an experience similar to The Velvet Sundown’s, but she took a different path.

When Billboard broke the news about Monet’s signing, a wave of media attention drove her on-demand streams and Google search traffic to a peak in mid-September. The week after the peak, Monet’s streams fell 24% — remarkably close to The Velvet Sundown’s 25% decline after its peak week. That could have been the beginning of a steep drop following the height of the public’s curiosity. Instead, Monet’s weekly streams stopped their downward decline and leveled off over the last three weeks. So why didn’t Monet suffer the same fate as The Velvet Sundown?

Velvet Sundown, Xania Monet

Billboard

A week after Monet’s streams hit their apex, Hallwood Media started securing radio play for her songs. In the first week — when her streams fell 24% — Monet’s songs were played just twice on broadcast radio, according to Luminate. But weekly spins rose to 109 the next week, then climbed to 423 and 485 in the next two weeks. By the most recent week (the period ended Oct. 16), Monet had something The Velvet Sundown didn’t: an aggregate radio audience of more than 1 million listeners.

Placed side by side, the charts representing The Velvet Sundown and Xania Monet show the difference between existing outside of the traditional music business and operating within it. Radio play helped turn Monet away from the cliff of disinterest and put her on a different trajectory. Without promotion, both radio and digital, it can be exceedingly difficult for any artist to maintain momentum — much less one created with AI.

Trending on Billboard Another day, another flood of music industry deals. How does one keep track? In an effort to provide an overview of the latest acquisitions, mergers, joint ventures, licensing agreements and more, Billboard publishes a list of all of the latest pacts that have hit our radar every other Thursday. Legacy management and […]

Trending on Billboard

A lot is changing at Spotify. In recent weeks, the company announced its founder and CEO, Daniel Ek, is stepping down from the CEO post (he will stay on Spotify’s chairman); it announced plans to develop generative AI music models with the support of the music industry; it updated its AI policies; it finally launched lossless audio; it updated its free tier; it forged new deals with a number of top music companies; and the company rolled out a number of new features, like direct messaging and “Mix With Spotify.”

The changes are a lot to keep track of, so on this week’s episode of Billboard’s new music business podcast, On the Record w/ Kristin Robinson, Spotify’s global head of marketing and policy, music business, Sam Duboff, joins to explain how the company is evolving, from a static destination for music consumption to what he calls “a place where fans can experience the whole world of an artist.”

Related

Duboff is one of the executives who determines how Spotify will handle the growing presence of AI music on its platform. He also is key in the development of Spotify for Artists, the company’s hub for musicians that enables them to manage their artist profiles and connect with fans.

Below is an excerpt of Billboard’s wide-ranging conversation with Duboff on this week’s episode of On the Record, focusing on its treatment of AI music on the platform.

Watch or listen to the full episode of On the Record on YouTube, Spotify or Apple Podcasts here, or watch it below.

I wanted to hear a little bit more about the fact that y’all are developing generative AI with the consent of many players in the music industry. There isn’t much information out there, so what is going on?

Duboff: We have been hearing from artists and their teams for a few years now that merging music AI tech products don’t feel like they’re built for them, not built for the power of their businesses, their careers, their existing fan bases. So we recently announced we’re collaborating with some of our top industry partners, across major labels and indies, to collaboratively develop artist-first, responsible AI music products.

So what would that look like?

We want to do this in consultation with the industry. People talk to artists about it, songwriters about it, and it feels like a lot of principles about AI and music and what these should look like. It’s happening in real time. So we didn’t want to wait until we have a product ready for a big launch to start talking about how we’re going to build AI products. We want to talk now, while we see lots of other folks in the industry are investing in the space, to be clear about our principles and how we’re gonna work with the industry for any product we build. So we’re looking at four key principles we outlined.

Related

First, [we have forged] upfront agreements with the music industry. [We are] not using tons of music [without permission] and asking for forgiveness later. Second, we wanna make sure artists, songwriters, rights holders have agency and choice about how their music does or doesn’t participate in these tools. They should have control and choice around how fans can or can’t interact with the music using AI. Third, we will always have proper monetization and compensation built in. So artists, songwriters, right holders [are] always compensated for all uses of their work [and] properly credited transparently. We’ll have an eye towards building new revenue streams for the music industry, so not just splitting up the existing royalty pool. We think that could be really important for powering what the next stage of the music industry looks like. Fourth, and really important to us, when we think about our role right now in music, is we want to build AI music products that deepen existing artist-fan connections. With 700 million monthly listeners coming to Spotify already, to listen to their favorite artists, we can play this really unique role where we build tools and help fans go deeper with their favorite artists and connect with their favorite artists in new ways, and make sure AI tools aren’t there to kind of compete with artists or to try to replace human artistry.

I know it is still very preliminary, but you talked about how this will increase the connection between fans and artists. Tell me if I’m off base, but it kind of sounds more like Spotify is leaning towards AI-powered remixing of current songs, rather than a model that generates a new song from scratch, like Suno or Udio, right?

Yeah. I think we see our role as the biggest streaming home for professional artists today. We facilitate those connections between artists and fans through their music already. So we think we’re best positioned to help have AI power this next stage of the industry. In some ways, it’s just in that space of existing artists and connections and building on artists’ catalogs with their consent. Yeah, not tools that are built to compete or kind of siphon off [royalties] from parts of the industry.

Related

To me, this signals a shift for Spotify. Spotify has always been the final destination for listening. This now feels like it’s a more playful, interactive music creation tool. Do you see Spotify continuing to expand from being the place for static streaming?

Over the past few years, we’ve been evolving Spotify from a place that’s just about the music to giving artists all these tools to share the world around their music. So three, four or five years ago, on Spotify, you get an artist profile with some pictures and canvases [looping visuals paired to songs]. It was mostly just about the music, and then you’d have to go to social media or elsewhere to experience the artist’s broader world. Where we’ve been focusing is bringing in artist clips so that artists can share 30-second videos, sharing the meaning of their songs, music videos, live performance videos, which we’ve launched in 100 countries outside the U.S. We’re working to bring that to the U.S. [There are] countdown pages that build up your album release. You can sell your merch in advance. We’re seeing artists use that in really creative ways. So we’ve already been on this journey of making Spotify a place where fans can experience the whole world of an artist. These AI music principles are an extension of that philosophy.

Spotify has also recently updated its policies on AI music. This included a note that the service has removed “75 million spammy tracks.” I’ve seen some outlets post stories about this figure incorrectly, calling it 75 million AI tracks, but it feels like the word “spammy” is intentional, referring to both AI spam and human-made spam. Can you explain what Spotify meant by this?

We’ve definitely seen modern Gen AI tools increase the scale of spam, and so certainly AI played a role in this scale. Not so long ago, there weren’t even 75 million tracks on streaming services, and now, we’re removing that many, but yeah, we’re working to identify spam, regardless of whether AI’s part of the creative process or not.

Related

Spotify is also working with DDEX to create a standardized way to disclose exactly how AI is used in the music creation process. It feels like a step in the right direction to create a standard, but if I’m a bad actor, why would I self-disclose? I probably wouldn’t.

We see this as the first step. No matter what the long-term solution is going to be, of the system of incentives and deterrence that will get people to disclose, the starting point has to be shared language through the existing supply chain of music about what the formatting of that will be.

But I think you do see already a lot of artists, songwriters, producers, starting to talk about how they’re using AI more often. So you see the K-Pop Demon Hunters songwriter who talked about brainstorming with Chat-GPT when he wrote “Soda Pop” through to Brenda Lee using AI to translate “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree” into Spanish, but still her voice. It was so cool, but it may have been confusing for Spanish listeners, if they thought Brenda Lee or any artist spoke a language they don’t speak. Now, [with the DDEX partnership] it will be really cool for them to know transparently [exactly how AI was used.]

When Spotify came out with these policies, it did feel like a start, but I heard from some people that they felt it didn’t go far enough. So, what do you say to those who feel like it’s not going far enough?

It’s early days for AI tech. I know it feels like it’s moving fast, but consumption of AI-generated music’s insanely low. We have some time for artists, songwriters, producers to take the lead in figuring out how they want to use these tools. We don’t want to act like we know where AI music’s headed and exactly every policy and role we need to future-proof for the next two or three years. But also, we didn’t just want to wait and do nothing. Some areas we all can agree now that we need to act now, no matter where AI tech heads. We think it’s going to be necessary to have great systems in place to stamp out spam, deception, impersonation. So that’s our starting point. We try to be upfront. We see these as first, critical early steps. There’s more to come.

Related

French streaming service Deezer reported recently that 28% of daily uploaded songs are fully AI-generated. That’s a shockingly high number. At Spotify, have you seen the same figures?

AI detection tech isn’t really foolproof yet. You know, every streaming service has pretty much an integral catalog. We have no reason to disbelieve it’s a similar amount on any streaming service. That said, I think they shared the point that .5% of streams is all those songs were getting. We’ve tried a few different tactics to test that — different detection tech, testing out different proxies — to understand how much prompt-generated music may be listened to on Spotify, and we find it is way lower than .5% in the share of streams, in total consumption. So I know sometimes it feels scary when you see those upload percentages…but yeah, there’s a lot of uploads [of AI music.] We’re doing a lot of work to release that kind of spam, where there are mass uploads that can add up to those kinds of percentages, but keeping a close eye on the part that actually matters, which is, are listeners listening to it? Is it generating royalties?

Consumption being really low makes me think that it must be a burden on streaming services to hold all of this music, especially when no one’s listening to it. Would Spotify ever remove tracks that are just getting absolutely no traction?

I don’t think so. Whether they’re AI or otherwise, people upload their music to streaming services for all different reasons. I have family members that upload music to send to family and friends. That’s a great thing at Spotify, [where] we are focused on emerging and professional artists. Our policies are in service of professional artists and emerging artists on their way to that. So we take on the burden of how many songs are uploaded, and certainly the overwhelming majority of songs aren’t getting streamed much. I still think it’s really important for there to be this open outlet.

Related

Is this a cloud storage issue? I have no idea how big these songs are to hold onto.

Maybe someday, with AI scale, it will be.

Earlier this year, I spoke to Spotify’s global head of editorial, Sulinna Ong, and I asked her about whether or not she would ever forbid AI tracks from living on Spotify editorial playlists. She didn’t have a clear answer at that moment — it wasn’t a yes or a no, so I wanted to ask again. Could you ever imagine fully AI-generated tracks living on a Spotify playlist?

It’s a hard question, because I think we recognize AI music as a spectrum… I think what you’re getting at is completely prompt-generated music without any human input. Is there some world where listener behavior really changes, and there’s huge musical, cultural relevance from music that doesn’t spam, deceive or impersonate, but somehow finds an audience, [that] could make it on to a viral hits sort of playlist? I can’t speak for their team, but fundamentally, 100% of the focus of our editorial efforts is helping to identify, uplift [and] develop the careers of professional artists who are making amazing music. So it’s always hard to answer that question in absolutes, but certainly that’s not the focus of anyone at Spotify, or, I think, any streaming service.

Given the enormous stakes at play, when business leaders talk about AI, people listen.

In May, Dario Amodei, CEO of AI firm Anthropic — who stands to personally benefit from companies’ widespread adoption of his technology — gained widespread attention after he predicted that AI will wipe out half of all entry-level jobs within five years. And in music, Sony Music CEO Rob Stringer, in an annual presentation to investors, said the company is “going to do deals for new music AI products this year” and that it has “actively engaged with more than 800 companies” on various AI-related initiatives.

Perhaps most notable, at least on the music front, are the comments made about AI in various interviews given by Spotify CEO Daniel Ek in recent years. In them, he’s provided insights into how Spotify, the most valuable and important music platform in the world, approaches the technology. Ek’s comments carry weight: While generative AI platforms such as Suno and Udio have stirred the greatest amount of fear over AI’s ability to undermine human creativity, the largest music platforms will play a huge role in how both creators and listeners engage with it.

Understanding Spotify’s approach to AI doesn’t always require reading tea leaves. Some of its products that use AI are out in the open. For example, in 2023, the company launched two major products that utilize the technology: a personalized AI-powered DJ and a voice translation tool for podcasters that can translate recordings into other languages. Still, given that the company’s attitudes and approaches to AI will affect Spotify’s 678 million monthly users and millions of creators, it’s worth examining Ek’s statements to see how Spotify intends to incorporate AI, embrace opportunities and address concerns. To that end, this author examined 10 podcast interviews, numerous online articles and a 2024 open letter Ek penned with Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg to get a better sense of how he views the technology. The one aspect about AI that Ek has talked about most often is its ability to help Spotify deliver to listeners the right audio — whether it’s music, a podcast or an audiobook — at a particular moment. He has described a mismatch between supply and demand, and how using new innovations can help better connect listeners and creators. Right now, Spotify users can search and find what they want 30% to 40% of the time, Ek told the New York Post in May, adding that he believes AI can improve that number. “So, we still have some ways to go before we’re at that point where we can just serve you that magical thing that you didn’t even know that you liked better than you can do yourself,” he explained. Most germane to people reading this article, the interviews show that Ek has consistently voiced a respect for creators and a belief that AI should enhance creativity, not replace it. That may not reassure songwriters who are receiving fewer royalties after Spotify adopted a lower royalty rate afforded to bundles in the U.S. Ek’s stated respect for artists also contrasts with the criticism Spotify has attracted — as detailed in the book Mood Machine and news reports — for paying flat fees for music tagged with fake artist names and inserted into playlists in order to reduce its royalty obligations. (Spotify denied claims that it’s created fake artists.) But in his public comments, Ek’s support for creators doesn’t waver, and there’s no indication that Spotify will follow in the footsteps of Tencent Music Entertainment, which offers music-making generative AI tools — it incorporates Chinese AI company DeepSeek’s large language model — and allows users to upload the resulting songs to its QQ Music platform. But AI can aid the creative process without stepping on creators’ rights, and Ek has talked with excitement about how AI tools can help lower barriers to entry and help musicians bring their visions to life. Although making music no longer requires learning and mastering an instrument, there’s still some technical know-how involved in producing music on digital audio workstations (DAWs). AI tools can reduce the complexity of DAWs and increase creators’ productivity. “We’re most likely going to have another order of magnitude of simplicity,” Ek said on the Acquired podcast in 2023. At the same time, Ek admits there are some frightening potential applications for AI. In 2023, he told CBS Morning that AI can make experiences in every field “better and easier,” while admitting that the notion that AI will be smarter than any human is “daunting to think about what the consequences might be for humanity.” And despite the potential for AI to unleash untold amounts of creativity, Ek admits that the ultimate outcome for creators is difficult to ascertain. “We want real humans to make it as artists and creators, but what is creativity in the future with AI? I don’t know,” he said in May at an open house at Spotify’s Stockholm headquarters, according to AFP. Just as lawmakers and music industry groups are pushing for legislation to protect artists’ names and likenesses, Ek has revealed concern about AI’s ability to replicate a musician’s voice. “Imagine if someone walked around claiming to be you, saying things that you’ve never said,” he told Jules Terpak in 2024. Spotify wouldn’t allow it on the platform without the artist’s permission, Ek said, citing Grimes — who launched a project in 2023 allowing fans to replicate her voice to use in their songs and evenly split the royalties — as an example of permissible use of an AI-generated name and likeness. “Of course, we will let her experiment, because she’s fine with it,” Ek said. Now that Spotify is in the audiobook business, the company’s use of AI will impact a wider swath of creators than just musicians. As Ek told The New York Post, Spotify “can play a role” in getting more books converted into audiobooks using AI — specifically smaller authors who can’t afford the expense of hiring someone to read them. Such affordable text-to-voice tools already exist and are offered to authors who would otherwise be locked out of the audiobook market. It makes sense: Just as Spotify was built on providing listeners the long tail of music, it doesn’t want its audiobook selection to be limited to major titles. If Spotify builds or buys such a tool, it could vastly increase the number of audiobooks available to its listeners. In the interview with CBS Morning, Ek quoted Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates to explain how he finds inspiration in innovation. “He says that the future is already here,” Ek said during the 40-minute talk. “It’s just not evenly distributed.” What Ek means is that he looks around the world, sees what others are doing with technology and then considers how he can bring those innovations to a wider audience. And as the CEO of the world’s largest and most influential audio streaming service, how he chooses to approach AI will go a long way in determining — for better or worse — how millions of people create, consume and profit from music, podcasts and audiobooks in the future.

Trending on Billboard

Artificial intelligence is a technology with profound implications — it will soon be smarter than we are! — including for the future of music. So far, though, the debate over the copyright issues involved in training AI algorithms follows a familiar pattern: Rightsholders want a licensing structure to generate royalties, while some technology companies maintain that they don’t need permission and others just proceed without it. To music executives of a certain age, it sounds a bit like the Napster battle, especially since the central issue is fair use. Technology companies seem to have the same plan: Move fast and break things, then try to change the law once consumers get accustomed to the new technology.

Could this time be different?

Trending on Billboard

Yes and no, at least to judge by the current state of affairs. In the European Union, which passed the first serious AI legislation, some lawsuits working their way through the courts now — perhaps most importantly GEMA’s case against Suno — will provide more clarity. The situation in the U.S., which seemed to depend on the result of major label lawsuits against Suno and Udio — in which the two sides are negotiating — has been complicated by President Trump’s firing of the Register of Copyrights. In the U.K., the government has been considering loosening copyright by calling for a consultation — but that effort has come under pressure from both music companies and creators.

Two weeks ago, at a party to honor the Billboard Global Power Players, Elton John and his manager and husband, David Furnish, won the first-ever Billboard Creators Champion Award for their work fighting the U.K. government’s proposed adjustments to copyright law. That initially involved an amendment to a data bill being debated in parliament that would have forced technology companies to be transparent about the content they used to train their algorithms. The bill repeatedly “ping-ponged” between the House of Commons and the House of Lords as the latter repeatedly voted for the amendment, under the leadership of Baroness Beeban Kidron. Last week, after more back-and-forth, the data bill passed without the amendment.

This bill doesn’t affect copyright, although the amendment would have, so it represents only a minor skirmish in what’s shaping up to be a serious fight. John and Furnish aren’t going away, and John’s consistent championing of upcoming artists gives them real moral authority. Other artists are with them, including Paul McCartney and the acts behind the “silent album.” There’s strength in numbers, and the days when companies like Napster could give Metallica a reputational black eye are long since over. Few artists and executives have devoted as much time to the issue as John and Furnish, but they aren’t alone. Besides artists, the entire music business is behind them.

They are also fighting a very different battle than Metallica was all those years ago. Back then, the Internet looked much cooler than major label music — more disruptive, in today’s terms — and Metallica got cast, unfairly, as trying to fight the next new thing. At this point, technology companies have grown into a new establishment, with far more political power than the media business ever had. Elton John doesn’t seem like he’s trying to stop the next new thing — he’s trying to make sure that new technology doesn’t get in the way of the next new artists. Metallica’s fight wasn’t actually all that different — people just didn’t understand it very well.

Technology companies are pushing some of the same ideas they always have, which now seem almost oddly old-fashioned. The idea is that governments need to relax copyright laws so they can “take the lead” or “get ahead” in “the AI arms race.” This sounds vital, and it is, except that the kind of AI that’s most important is general intelligence, which has very little to do with the kind that can make new songs in the style of, say, Led Zeppelin. That’s just a consumer product. Also, what exactly are governments racing toward? Since AI is expected to eliminate white-collar jobs and the tax revenue that flows from them, what exactly is the hurry?

The debate over the U.K. data bill was only just the beginning, and the way John and Furnish framed the issue could influence the debate as it develops. For the next few years, both sides will argue about how compensation will work. But without the kind of transparency that the amendment to the bill mandated, it would be very difficult for technology companies to identify and pay the right creators. Transparency is necessary but not sufficient — it won’t solve the problem, but there can’t be a solution without it. Any serious conversation about compensating artists for the use of their work in AI needs to start there, and thanks to creators, this one has. Let’s see where it goes from here.

Sony Music CEO/chairman Rob Stringer spoke to investors on Friday (June 13) about his vision for how generative AI can be integrated into his business, stating that the company is “going to do deals for new music AI products this year with those that want to construct the future with us the right way.”

To date, Stringer says the major music company has “actively engaged with more than 800 companies on ethical product creation, content protection and detection, enhancing metadata and audio tuning and translation amongst many other shared strategies.” He went on to say that he believes “AI will be a powerful tool in creating exciting new music that will be innovative and futuristic. There is no doubt about this,” but later added: “So far, there is too little collaboration, with the exception of a handful of more ethically minded players.”

Stringer’s statements about the emerging tech, which he made at Sony Group’s 2025 Business Segment Presentation, arrived just a week after news broke that Sony — and its competitors Universal Music Group and Warner Music Group — were engaged in talks with generative AI music companies Suno and Udio about creating a music license for their models. Suno and Udio are currently using copyrighted material, including music from the three majors, to train their models without a license. This spurred the trio to file blockbuster lawsuits against Suno and Udio in June 2024, in which they alleged copyright infringement on an “almost unimaginable scale.”

Trending on Billboard

In his remarks on Friday, Stringer likened the current AI revolution to “the shift from ownership to streaming” just over a decade ago. “We will share all revenues with our artists and songwriters, whether from training or related to outputs, so they are appropriately compensated from day one of this new frontier,” he said.

“I do think that what AI is based on, which is learning models and training models based on existing content, means that those people who have paved the way for this technology do have to be fairly treated in terms of how they get recompense for that usage in the training model,” Stringer continued. “We have been pretty clear on this since day one that there is absolutely no backwards view as to what this technology will do. There will be artists, probably there will be young people sitting in bedrooms today, who will end up making the music of tomorrow through AI. But if they use existing content to blend something into something magical, then those original creators have to be fairly compensated. And I think that’s where we are at the moment.”

There are challenges ahead to figure out proper remuneration for musical artists from generative AI, as Billboard recently described in an analysis of the Suno and Udio licensing talks. While the AI license could borrow the streaming licensing model by having AI firms obtain blanket licenses for a company’s full musical catalog in exchange for payment, it remains to be seen how the payments would be divided up from there. On streaming services, it’s simple to determine how often any given song is consumed and to route money to songs based on their popularity. But for generative AI, the calculation would be far more complicated. To date, Suno and Udio do not offer guidance as to which tracks were used in the making of an output, and experts are divided on whether or not the technology needed to figure that out is ready yet.

Also on Friday, Stringer expressed a desire to come to agreements with AI companies in a free market, stating: “With deals being carried out, it will be clear to governments that a functioning marketplace does exist, so there is no need for them to listen to the lobbying from the tech companies so heavily.”

Today, many AI companies don’t believe they need to license music or other copyrights at all, citing a “fair use” defense. But in his statements, Stringer was optimistic that this would change, citing the recent position of the U.S. Copyright Office, which said that “making commercial use of vast troves of copyrighted works, especially where this is accomplished through illegal access, goes beyond established fair use boundaries.” One day after publishing this position about the value of copyrights in the AI age, however, the Register of Copyrights, Shira Perlmutter, was fired by President Donald Trump. (Perlmutter sued soon after, calling Trump’s move “unlawful and ineffective.”)

“We are between us and the AI tech platforms trying to find common ground,” Stringer continued. “And that common ground is not going to take a minute. It’s going to take a moment, and then it’s going to take the trial and error process, and we are in that era right now.”

The RIAA is throwing its support behind a blockbuster copyright lawsuit filed by Disney and Universal against artificial intelligence firm Midjourney, calling the case “a critical stand for human creativity.”

The lawsuit, filed earlier on Wednesday (June 11), claims Midjourney has stolen “countless” copyrighted works to train its AI image generator — and it marks the first foray of major Hollywood studios into a growing legal battle between AI firms and human artists.

Disney and Universal’s new case, which comes as major music companies litigate their own infringement suits against AI firms, “represents a critical stand for human creativity and responsible innovation,” RIAA chairman/CEO Mitch Glazier wrote in a statement.

Trending on Billboard

“There is a clear path forward through partnerships that both further AI innovation and foster human artistry,” Glazier says. “Unfortunately, some bad actors — like Midjourney — see only a zero-sum, winner-take-all game. These short-sighted AI companies are stealing human-created works to generate machine-created, virtually identical products for their own commercial gain. That is not only a violation of black letter copyright law but also manifestly unfair.”

AI models like Midjourney are “trained” by ingesting millions of earlier works, teaching the machine to spit out new ones. Amid the meteoric rise of the new technology, dozens of lawsuits have been filed in federal court over that process, arguing that AI companies are violating copyrights on a massive scale.

AI firms argue such training is legal “fair use,” transforming all those old “inputs” into entirely new “outputs.” Whether that argument succeeds in court is a potentially trillion-dollar question — and one that has yet to be definitively answered by federal judges.

Disney and Universal’s new lawsuit against Midjourney is the latest such case — and immediately one of the most high-profile. The 110-page lawsuit claims the startup “helped itself” to vast amounts of copyrighted content, allowing its users to create images that “blatantly incorporate and copy Disney’s and Universal’s famous characters.”

“Midjourney is the quintessential copyright free-rider and a bottomless pit of plagiarism,” the companies wrote in their complaint, lodged in Los Angeles federal court on Wednesday morning.

The case echoes arguments made by Universal Music, Warner Music and Sony Music, which filed their own massive lawsuit against the AI music firms Udio and Suno last summer. In that case, the music giants say the tech startups have stolen music on an “unimaginable scale” to build models that are “trampling the rights of copyright owners.”

Music publishers have filed their own case, accusing Anthropic of infringing copyrighted song lyrics with its Claude model. Numerous other artists and creative industries — from newspapers to photographers to visual artists to software coders — have launched similar cases.

Disney and Universal’s complaint makes the same basic argument — that using copyrighted works to train AI is illegal — but does so by citing some of the most iconic movie and TV characters in history. Disney cites Darth Vader from Star Wars, Buzz Lightyear from Toy Story and Homer Simpson from The Simpsons; Universal mentions Shrek, the Minions, Kung Fu Panda and others.

“Piracy is piracy, and whether an infringing image or video is made with AI or another technology does not make it any less infringing,” lawyers for the studios write. “Midjourney’s conduct misappropriates Disney’s and Universal’s intellectual property and threatens to upend the bedrock incentives of U.S. copyright law that drive American leadership in movies, television, and other creative arts.”

State Champ Radio

State Champ Radio