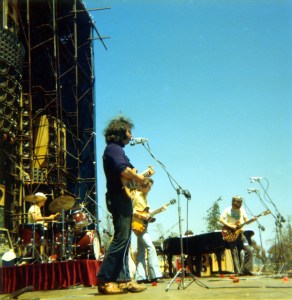

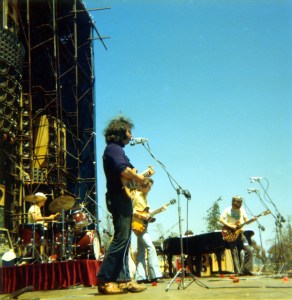

The Grateful Dead (L to R: Bill Kreutzmann, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Phil Lesh) perform on May 25, 1974 at Santa Barbara Stadium in Santa Barbara, California with their Wall of Sound.

Ed Perlstein/Redferns/Getty Images

This August, Dead & Company will celebrate 60 years of Grateful Dead music with three massive concerts in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Fans can reasonably assume – as they can with most major touring artists today – that the sound will be impeccable.

But six decades ago, when the Grateful Dead began gigging around that very same park, quality sound was far from a given. Audiences routinely endured terrible audio, and bands also struggled to parse the noise and play together. Modern cornerstones of concert production, from monitors to digital delay towers, had yet to be invented.

The Grateful Dead didn’t just embrace new advancements in audio technology – as journalist and Deadhead Brian Anderson chronicles in his new book, Loud and Clear: The Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound and the Quest for Audio Perfection, the revered band actively drove concert sound forward, creating many of today’s standards in the process.

Loud and Clear specifically tackles the first decade of the band’s history, from its Bay Area formation in 1965 to the Wall of Sound, the gargantuan sound system worth nearly $2 million in today’s dollars that it took on the road in 1974. During those years, the band and the cast of characters in its orbit – from an audiophile LSD chemist to hard-nosed roadies – continually iterated its sound system, introducing numerous innovations in service of creating a deeper performer-listener connection through quality sound. The pinnacle was the Wall of Sound, a technological marvel that towered behind the band and allowed each musician to manipulate their individual mixes in real time.

“I knew this was for a general audience,” says Anderson, who asked himself, “How do I make it digestible and explain this stuff in a way people are gonna understand?” The son of Deadheads – who saw the band repeatedly in this era and took him as a toddler to see the Dead at Alpine Valley in the late ‘80s – found the answer in those strong personalities within the Dead’s organization. Loud and Clear is as much a story about the Dead’s audio equipment as it is about the band’s musical philosophy and the way money, fame, and excess challenged it.

“The wheels came very close to coming off,” Anderson says of the Dead in this era. The band took the Wall of Sound – which, when its almost 600 speakers were assembled, measured 60 feet long and more than three stories tall – on the road for nearly 40 shows in 1974, and the unprecedented production feat came close to bankrupting the Dead and tearing it apart. Plus, at a time with far fewer regulations, transporting, assembling, and disassembling the Wall came with plenty of risks for the (often inebriated) crew tasked with doing so; Loud and Clear’s at-times harrowing narrative includes broken arms, nearly-severed toes, falling equipment, electrocutions and flipped trucks. “It’s amazing that nobody bit it,” Anderson says.

The Dead ultimately carried many of the lessons of the Wall of Sound into the proceeding years – but after taking a hiatus in 1975, returned without the advanced system in 1976. “They somehow kept it together,” Anderson says, “but there was a collective sigh of relief at the end of 1974 when they’re like, ‘OK, you know what? Let’s take a break here.’”

The Grateful Dead (L to R: Bill Kreutzmann, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Phil Lesh) perform on May 25, 1974 at Santa Barbara Stadium in Santa Barbara, California with their Wall of Sound.

Ed Perlstein/Redferns/Getty Images

What inspired you to write a book not just about the Dead, but about such a specific topic and period?

I am the child of early Deadheads who both started seeing the band in the late ’60s and early ’70s in Chicago and the tri-state area. I grew up hearing them talk about the Wall of Sound and this system’s sonic clarity. They would talk about seeing the band perform with this massive assembly of gear behind them – and it’s called the Wall of Sound, so it’s just captivated me my entire life.

As time went on, I grew to appreciate the scale of the Wall. When I was at VICE, I was the Features Editor [at science and tech vertical Motherboard], and I thought it would be cool to do a deep dive into the Wall of Sound. I embarked on writing that initial story because I knew that it had more than just the technology component – it’s a story about obsession, obsessive people who came from all walks of life. After that story came out, it quickly dawned on me that there’s so much more here – like, maybe I could do a full book on this one day.

How did the Dead’s pursuit of quality sound differentiate themselves from their peers and ultimately help them amass the following that they did?

Not long after the band had gotten going, [singer/guitarist] Jerry Garcia’s mother, Ruth, purchased her son a pair of Klipsch speakers. That was, basically, the very first iteration of the Dead’s sound system. No other bands at the time had their own rig like that, so immediately, they were elevated above most of their peers, at a time when musical PAs didn’t exist. Most any club that they were playing at the time, if it did have a sound system, it was just a small little box to like each side of the stage. The famous example, on a bigger level, is the Beatles at Shea Stadium. Live sound presentation in the mid ’60s was kind of terrible.

Then they get hooked up with Owsley Stanley, who was their patron and their original sound man. He was using money that he was making from manufacturing LSD to bankroll the band. He was kitting them out with top-flight gear by early 1966 – and right around that time, the acid tests were getting going. The Dead were basically the in-house band at the acid tests, and the acid tests would be the model that they would follow, really, through the end of their career: During the acid tests, the band and the crowd were all the same organism, everyone was in the same sonic envelope.

The whole point of putting [all the audio equipment] at the musicians’ backs [in the Wall of Sound in 1974] was to ensure that the band and the crowd would all hear the same thing and be in the same sonic envelope together – and that harkened right back to the acid tests. There’s also an ethic with the Dead that was there from the very early days: That ethic was to present the sound in such a way that the person in the very back row would experience the exact same thing as someone who was hanging right on the barrier. Part of their righteous approach to sound was to present the sound in such a way that everyone in the space together [would] experience the same high quality.

At its roots, the Dead almost had a punk-like, DIY ethos. What tensions did that introduce as the band’s operation grew and professionalized?

By the early ’70s, the sound system that was growing into the Wall of Sound had become the center of the Dead’s homegrown world-building project, which included their own record label, in-house travel and booking agencies, a publishing arm, and a whole cottage industry of boutique sound and audio companies that were building kit for the Dead. [The Dead wanted] to do everything their own way; it didn’t necessarily make sense to do what they were doing, but they did it anyway. It was super, super punk, super DIY.

From the very beginning, they would always funnel money back into their sound system – that’s basically how the Wall of Sound was able to grow. As early as mid-1973, management was starting to be like, “Hey guys. We can’t do things like we did in the very early days.” It became clear that they were hemorrhaging money through this sound system. By mid-’74, it was starting to get through to Garcia and some of the other band members that this was not sustainable. Despite their wanting to continue on in this very punk, DIY fashion where money would just always be funneled back into the sound system, the reality was such that they couldn’t do that anymore.

As much as the book is about the band, it’s also about the crew that surrounded it. Why emphasize those supporting characters?

I knew that if I was gonna do this book, I had to push the story forward somehow. I didn’t want to just tell this story through old sound bites from Jerry Garcia or Bob Weir or Phil Lesh. There were so many other people who were in the room in this era who helped put this thing together and who made it go on the road, setting it up and tearing it down. I was really interested in illuminating what the day-to-day was like of conceiving [the Wall of Sound] and building it and taking it on the road. I wanted stretches of the book to kind of feel like you’re going on tour with them.

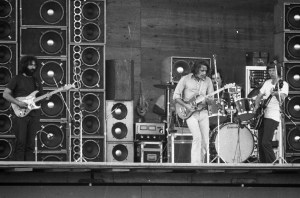

The Grateful Dead at The Summer Jam at Watkins Glen rock festival at Watkins Glen, New York on July 28, 1973.

Richard Corkery/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

Your book outlines several audio innovations by the band, including pioneering the use of on-stage monitors, helping to invent digital delay towers, and using feedback-cancelling microphones to make the Wall of Sound work. What were the most significant lasting impacts the Dead had on modern concert audio?

There’s a number of them. A curved speaker, no one had done that before the Dead. The theory and the mathematics existed, so a curved speaker existed on paper, but the Dead were really the first to fly a curved speaker. Today, you go to see Metallica at a stadium or you go see a local punk band at the dive bar, you’re gonna see versions of a curved speaker – and that’s the Dead lineage.

Delay towers, that’s not the Wall of Sound, but an adjacent sonic first that the Dead and their crew and their technicians helped forge in that era. Kezar Stadium, RFK, Watkins Glen, those three [big outdoor concerts] in summer of ’73 were crucial to figuring out digital delay. That’s another convention of modern sound reinforcement at much bigger shows that anyone is familiar with.

From a philosophical standpoint, a lasting impact of all the Dead’s innovations in the audio realm in this era was an elevated presentation. The Dead instilled this awareness of pursuing the highest-quality sound that you can because you owe it to your audience, because these people are coming to see you perform.

And in turn, that reoriented what fans expected of concert audio, not just at the Dead’s shows but at any show.

By the time the Dead came back from their hiatus in 1976, the world of audio had kind of caught up to them. They realized, “We don’t need to carry this massive equipment with us anymore, because the state of the art has advanced to a point where we can rent a sound system that sounds just as good, if not better, than the Wall of Sound for a fraction of the price.” A lot of that really owes to the ground that they broke through the Wall of Sound.

At a couple points in the book, you quote Garcia interviews from this period where, when lamenting the challenges of ensuring quality audio on tour, he says he wishes the band could have its own venue tailored to its own production standards. That never came to pass – but today, Dead & Company has played upwards of 40 shows at Sphere in Las Vegas. What would Jerry have thought of Sphere?

Last year, the first time I went to the Sphere, walking in, I couldn’t help but draw all of these connections. In the very early ’70s, they were always having conversations about, “Gee, wouldn’t it be great if we had our own spot where we could set up our sound system, just exactly perfect, and people can come see us perform?” They started to take some very serious steps to figure out, “OK, what would this space look like?” One of the ideas they were kicking around was a Buckminster Fuller-style geodesic dome – like a sphere. So, you walk into the Sphere to see Dead and Company, it’s like, “Oh, here it is.” Inside of the Sphere is basically the Wall of Sound, but taken to an exponential degree. The Wall of Sound walked so the Sphere could run.

I have to think Garcia would’ve been tickled to take the Sphere for a ride. There’s the public perception of Garcia as this wooly, hippie-type guy, but he was always embracing the cutting edge, from the gear that he was playing and just experimenting with to getting really into computers in the late ’80s and early ’90s. He just loved, like, f—king around with the newest technology.

What’s your favorite Wall of Sound show?

June 16, 1974, at the Des Moines Fairgrounds, for sonic and setlist reasons as much as personal reasons – my mother was at that show. That show, to me, is the epitome of your outdoor Grateful Dead show in the sun in the summertime. An amazing show. [Editor’s note: Selections from this show were officially released in 2009 as Road Trips Volume 2 Number 3, which is available on streaming platforms.]

Loud and Clear: The Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound and the Quest for Audio Perfection will be released by St. Martin’s Press on June 17.

Loud and Clear.

Courtesy Photo