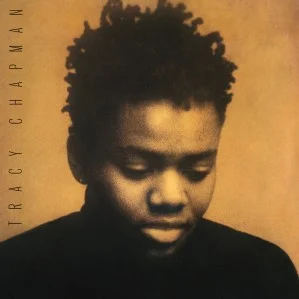

Tracy Chapman, ‘Tracy Chapman’

Courtesy Photo

Upon the arrival of Tracy Chapman’s self-titled debut on April 5, 1988, Billboard heralded the album as filled with “rich, haunting music,” praising both Chapman’s “husky, forceful voice” that “recalls Phoebe Snow and Joni Mitchell” and her poignant writing that tackled racism, injustice and an aspirational yearning for a better life.

Bolstered by first single “Fast Car,” the now-classic album has gone on to sell more than 20 million albums worldwide, and Chapman was recently introduced to a new generation of fans through country superstar Luke Combs’ 2023 “Fast Car” cover that topped Billboard’s Country Airplay chart for five weeks.

Chapman and the album’s producer, David Kershenbaum, had long been looking for a reason to revisit the seminal set on vinyl as the milestone anniversaries rolled by and, finally, the right moment arrived. “We might have talked about it at 25 years or 30 years, and then it just seemed like, ‘OK, this is a moment to do it because people have this renewed interest in vinyl and obviously this record was so extremely important to me and my career as a songwriter,’” Chapman says of the 35th anniversary.

Though widely available on streaming services, Chapman’s record collector friends were telling her that the original Elektra Records album was hard to find on vinyl, and even she was running short on copies— so much so that on the occasions Chapman wanted to revisit the album, she would listen on CD to keep from wearing out her few remaining vinyl copies.

So Chapman wrote a note to Mark Pinkus, CEO of Rhino Entertainment, Warner Music Group’s catalog division. “I said I wanted to make a faithful reissue,” she says. “I wanted it to sound as good or better than the original and to look like the original.”

The reissue, which came out Friday (April 4) via Rhino, overshot the 35th anniversary by two years, but that’s because she and Kershenbaum put so much meticulous care into the new version that it took way longer than they expected when they started in 2022.

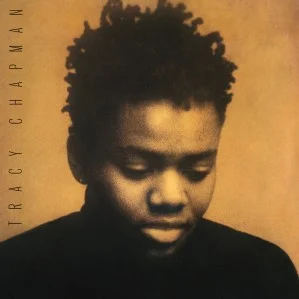

Tracy Chapman, ‘Tracy Chapman’

Courtesy Photo

Three decades later, Chapman unabashedly says she “loves the record. I mean I’m not unbiased,” she says with a laugh. “I’m just so proud of it. I was [proud] the day that we finished it and in the days when we were making it. It holds up for me. I have a lot of positive feelings about the whole process. Then what was created and then now, what [we] managed to achieve by bringing it back.”

In their first ever interview together, she and Kershenbaum display an easy rapport with evident respect, affection and trust as they revisit creating the original album and working together on the reissue. The intensely private Chapman, 61, rarely gives interviews, but throughout the nearly hourlong telephone conversation, she is upbeat, warmly engaging and thoughtful.

As the well-known story goes, Chapman was attending Boston’s Tufts University in the mid-‘80s and playing in local coffeehouses when she was discovered by fellow student/future A&R executive Brian Koppelman, who played a tape of her music for his father, Charles Koppelman, then-co-owner of music publishing company SBK Songs. That led to Chapman signing with Elektra when she was in her early 20s.

But recording her debut album got off to a rocky start. Alex Sadkin, the initial producer Elektra paired her with, died in a July 1987 car accident before they began recording, and a subsequent effort wasn’t the right fit. “I was put into a studio with really great musicians, and it just didn’t work because it was just too much for me and too much for the songs. I was being overwhelmed,” says Chapman, who had never played her own songs with other musicians and had very little experience playing music with other people at all. “I was briefly in a little cover band in my dorm. We only had two songs that we never played out and I was playing drums,” she says with a chuckle.

By the time she met Kershenbaum in SBK’s conference room, “I was worried at that point,” she admits. “I had a couple of false starts.” But Kershenbaum, who had worked with artists including Cat Stevens and Joan Baez, had already heard seven of Chapman’s songs and was in. Then, at their second meeting, Chapman played Kershenbaum a tape of the achingly sad “Fast Car,” and he was “totally blown away,” he says. ”It was perfect in every respect: from the emotional message, the lyric, the fact that everybody has a situation sometime in their life they would like to get in a car and just drive away,” he says. “It was the strongest thing that I probably ever heard in an initial demo.”

Though Chapman had spent virtually no time in a recording studio, Kershenbaum remembers her seeming “incredibly confident, a rock,” as they recorded over eight weeks at his Powertrax Studio in Los Angeles.

Chapman attributes that self-assurance to Kershenbaum. “He made me feel so comfortable and he was supportive from the beginning,” she says. “[Previously] I was feeling like ‘Nobody’s really listening to me.’ We had good communication from the start. He understood what I was doing musically, and he didn’t want to change it.”

That included recording the album live with all musicians playing together instead of the more conventional method of recording each instrument at a time.

“It was unorthodox the way we approached it, where we tried different bass players and drummers with Tracy’s guitar and vocal. And it was just a natural evolution,” Kershenbaum says. Ultimately, he selected drummer Denny Fongheiser and bassist Larry Klein.

“Many times, they are all that’s playing along with Tracy. It’s a third of the record,” he says. “So I had to be careful that they were really supporting what she was doing and not distracting because she had to be at the forefront of this.”

The studio became Chapman’s safe haven. “When the record company flew me to Los Angeles, it was the first time I’d ever been there,” she says. “They put me up in one of these [corporate] hotels. I was totally by myself, no manager, no assistant, no family. [The studio] was my social life, my work life, that was everything [while] we were making the record, and [David] made me feel so welcome and so comfortable and so cared for in the process.”

The pair knew the album would open with “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution,” a call for social change that Chapman wrote when she was 16. “To me, it was obvious that that was our starting point,” she says. “It’s the introduction, in a way, to everything else that follows. It alerts you that these are serious songs that are on the way. We didn’t try to hide that song, which I think certain people might have been inclined to do because of the subject matter.”

Across the set, she was fearless in tackling domestic abuse on the chilling, a cappella “Behind the Wall,” racism on “Across the Lines” and class warfare on “Mountain o’ Things.”

Even though Chapman was an unproven new artist, the label took a hands-off approach. “We never really even saw them or heard from them until we started sending finished stuff,” Kershenbaum says.

Chapman also felt free to create without commercial expectations, in part because her largely acoustic, weighty songs were so far removed from the bouncy pop delights like George Michael’s “Faith” and Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” dominating radio.

“I have to credit [then-chairman of Elektra] Bob Krasnow, who signed me,” she says. “Right away, he was a champion, and he never talked to me about changing anything.”

The only conflict with the record label came after “Fast Car” was picked as the first single and Elektra said the 4:57 album version was too long to receive radio play. Chapman initially refused to allow an edit. “I was adamant that we couldn’t cut any of the lyrics,” she says. They compromised by deleting some of the instrumental turnarounds, shortening the radio and video versions to 4:27, which was still longer than the average radio tune. The song reached No. 6 on the Billboard Hot 100.

After the album came out, Chapman was thrust into a dizzying array of live gigs with musical superstars, filling in for a delayed Stevie Wonder at Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday tribute concert at Wembley Stadium; joining the Amnesty International tour with Bruce Springsteen, Sting and Peter Gabriel; and opening for Bob Dylan (who wished her happy birthday via X on March 30).

Tracy Chapman went on to earn six Grammy nominations for the 31st annual Grammy Awards, with Chapman taking home trophies for best new artist, best pop vocal performance, female, and best contemporary folk recording.

Despite the Grammys declaring the collection a folk album and critics and fans labeling her a protest singer because of her issues-oriented, acoustic-guitar-based songs, Chapman has never seen herself that way.

“There was no folk scene that I’m aware of in Cleveland in the ‘70s. Maybe there was, but not one for an 8-year-old black girl,” she says. “It’s the acoustic guitar part that I think often makes people put me into the folk category. It is not a label I choose for myself, and I’m not really interested in looking at genres in that way. I’ve always loved all different kinds of music.

“I actually grew up listening to mostly R&B and soul music and gospel music and some jazz and rock & roll because that’s what was on the radio,” she continues. “I was a huge fan of Casey Kasem and his Top 40 Countdown. I used to record it on a little steno recorder so I could listen back.”

She credits picking up the acoustic guitar when she was 8 to watching the country variety show Hee Haw, a staple in homes across America in the early ‘70s on Saturday night. In addition to corn-pone sketches about rural life often with country comedian Minnie Pearl or a bevy of scantily clad beauties nicknamed the Hee Haw Honeys, the series featured stellar musical performances helmed by virtuosos like Roy Clark and Buck Owens.

“My mother loved the show, and so whatever she liked to watch on television, we watched too,” she says. “Buck Owens on the acoustic guitars. I think I fell in love with the instrument when I heard it on that show.”

Chapman asked her mom to buy her a guitar and “even though she didn’t have a lot of money, she managed to pick up one for me,” she says. Chapman taught herself how to play from books she checked out of the library and a class at the Boys & Girls Club.

By the time Chapman performed “Fast Car” with Luke Combs at the 2024 Grammys, 35 years after she first played the song on the 1989 Grammys, she and Kershenbaum were already hard at work on the reissue. (“I was quite weepy after, for some time,” she says of appearing on the Grammys with Combs. “Not so much from having played the song, but from the emotional experience of it all and also reuniting with Denny Fongheiser and Larry Klein. That was also very emotional. We were all crying at rehearsal.”)

Their reissue work had begun nearly two years earlier after they unearthed engineer Bob Ludwig’s original master of the album in the Warner Music Group archives, from which engineer Bernie Grundman created a lacquer to make a new master to press the new vinyl.

As the pair proceeded, Chapman took a vinyl copy of the original that she had never opened to use as a reference guide for the artwork and the sound quality “because it had no scratches, no dust, it had never been played,” she says.

They were zealous about their faithfulness. Through ever step “we would compare what we were doing now with what we had originally because we wanted people to be excited about it, not disappointed,” Kershenbaum says. That proved challenging because technology had advanced with different machines and methods since manufacturing the original. “[We were] going back and forth between” the new and old versions, “trying to make sure that what we were doing was as good or hopefully better than what we had,” he says.

The process was not without its disappointments. They reviewed test pressings for distortion and other flaws, giving feedback to the pressing plant in Germany. “There was a perfect test pressing the second time around and there was a speck of dust or something [causing] a huge pop on one of the songs and so the whole thing was ruined, which was unfortunate,” Chapman says.

They were just as painstakingly exacting with the artwork, including the stunning cover photograph by Matt Mahurin.

“We discovered as we started getting into the process that the record plants now don’t have a standard size for the cover,” Chapman says. “If we had reproduced the cover at either a larger or smaller size, it would have distorted as a photo. It would have made my chubby cheeks even chubbier.” Ultimately, Optimal Media in Germany created a new die that would match the size and scale of the original cover.

They were also slowed by international shipping delays and COVID precautions, leading to missing the actual 35th-anniversary deadline.

“It did take longer, but I’m really, really pleased with how it all ended up because we were just trying to get it right,” Chapman says. “I was disappointed to miss that actual milestone, but I think I would have been a lot more disappointed to have put something out that we all didn’t feel was 100% as good as it could be.”

All these years later, Chapman says the vivid, sympathetic characters she created on the album still live with her. “On a practical level, I’ve never really thought about, say, writing a song to continue the story of any of these characters in particular. But I think they are representing something emotionally for me, even if it’s not my own personal life story, that is still true for me now. I still have these feelings that you still want to find a sense of belonging. It’s a feeling that doesn’t necessarily go away.”

Chapman, who hasn’t toured since 2009, has no plans to play live again, but doesn’t rule it out. “If I were to tour, I would tour for something new, new material, and in that process, I would, of course, play these songs, too. But that would be the thing that would be most interesting to me at this point. And that’s always the case. Whenever someone asks, ‘What’s your favorite song?’ It’s always the one I’m writing at the time.”

And yes, that does mean she is writing. Though she hasn’t released an album of new material since 2008’s Our Bright Future, Chapman stresses that she’s never stopped. “I said it before, but maybe no one believed it, that I’m always playing and I’m always writing songs. I’ve been doing it since I was 8 years old. It’s just part of my DNA. It’s part of who I am.”